Vol. 41 (Issue 17) Year 2020. Page 24

STENDARDI, David 1; PÉREZ, Elena 2; CASTILLO, Alicia 3; GARCÍA, Juan Israel 4

Received: 20/02/2020 • Approved: 05/05/2020 • Published 14/5/2020

ABSTRACT: In this article we present the work that has been carried out within the research project "Society and Archaeological Heritage. Recovery of the Archaeological Heritage of Buenavista del Norte (Tenerife, Canary Islands), in rural and urban areas (PARQ_BVISTA)". The objective of this research is the elaboration of an interpretative and operational framework, oriented towards the creation of citizen participation networks in the management of cultural heritage. The study is based on an articulated methodology that combines the multidisciplinary perspective of the research team with qualitative and quantitative social research techniques. It comprises of focus groups, in-depth interviews to administrators and businesspeople and a questionnaire for local citizens. |

RESUMEN: En este artículo presentamos el trabajo que se ha llevado a cabo dentro del proyecto de investigación "Sociedad y Patrimonio Arqueológico". Recuperación del Patrimonio Arqueológico de Buenavista del Norte (Tenerife, Islas Canarias), en zonas rurales y urbanas (PARQ_BVISTA)". Este proyecto está financiado por las fundaciones La Caixa y CajaCanarias, y está formado por investigadores de diferentes universidades. El objetivo de esta investigación es la elaboración de un marco interpretativo y operativo, orientado a la creación de redes de participación ciudadana en la gestión del patrimonio cultural. El caso estudiado es el de Buenavista del Norte, una pequeña ciudad en una región remota del norte de Tenerife (Islas Canarias). El estudio se basa en una metodología articulada que combina la perspectiva multidisciplinar del equipo de investigación (arqueología, arquitectura, geografía, sociología, turismo, etc.) con técnicas de investigación social cualitativa y cuantitativa. Se compone de grupos focales, entrevistas en profundidad a administradores y empresarios, y un cuestionario para los ciudadanos locales. |

The study of the cultural landscape has been developed from disciplines as diverse as geography or archeology. At the moment, the research on this type of cultural asset also includes additional perspectives such as sociology, architecture, anthropology or tourism, among others. The analysis of these realities is complex: different disciplines concur in order to build integral methodologies, adapted to the context. The research project "Society and Archaeological Heritage. Recovery of the Archaeological Heritage of Buenavista del Norte (Tenerife, Canary Islands), in rural and urban areas (PARQ_BVISTA) " is based on this idea. This paper is inserted in this global approach of the project and focus on the elaboration of an interpretative and operational framework, oriented towards the creation of citizen participation networks in management of cultural heritage. The sociological perspective is mixed with concepts from anthropology and touristic studies.

Starting questions are related to the definition of a cultural landscape itself. Is it really possible to create a conceptual connection between local identity and tourism? Could cultural heritage be the element of this connection? How can we traduce operationally these concepts in order to improve heritage management and, at the same time, tourism management? It is evident that the elaboration of these answers requires several specific researches. Our proposal is following the path of social perception and social participation. Furthermore, we maintain the focus on the touristic phenomenon, since we consider its role in the interpretation of cultural heritage.

Our objective is to approach these questions through the study of the case of Buenavista del Norte, a small town in Tenerife Island. It represents an interesting case because of its geographical position and its natural and social characteristics. The distance from the touristic areas of the island, the importance of natural landscape and the particular rural local identity are necessary elements of the definition of place of study. We add that global transformation of tourism has determined the growth of the number of tourists visiting Buenavista. This phenomenon has accelerated the process of creation of the idea of cultural heritage in the municipality, transforming the definition and regulation of heritage resources by the public administration (top-down), and the perception of local community as well as actions derived from it (bottom-up).

This paper considered four issues with the aim to study the particular connection between them, based on the perception of local residents: identity, participation, heritage management and tourism. The method to detect social perception is complex but coherent. The first step is a previous descriptive multidisciplinary study to observe the characteristics of the area form different perspectives (archeology, architecture, geography, touristic studies and sociology). Based on reports of the experts of the research team, we organized two complementary levels of fieldwork. The qualitative part includes focus groups and in-depth interviews. The quantitative part is structured with an articulate survey, representative of the entire population of Buenavista.

The paper creates a specific theoretical framework for concepts and challenges proposed, and the corresponded particular methodology. Afterwards, we describe significant aspects of the municipality. The results presented follow the four-element scheme described. The quantitative data together with the analysis of groups and interviews express the social perception of identity, participation, heritage management and tourism. Finally, thanks to the discussion related to our theoretical framework we organize conclusions, without losing practical implications of our study.

A general definition of the identity is always a complex issue. In this case we propose a declination of the concept, considering social and geographical dimensions of our case. Thus, the isolated identity comprehends the self-perception of residents and the environmental position, agreed in terms of distance.

The difficulty increases because the construction of a collective identity is elaborated through social features. Values, attitudes and space organization contribute to establish identity (Olmo, 2012), considered through the individual and collective dimension.

Related to the context of Canary Island, in his analysis, Estévez (2011) elaborates two couples of categories, two couples of archetypes in order to study the “Canarian” identity, crossing the historical development of the archipelago. These four elements have to be read in their relation, continuously mutable. Thus, the representations of native (Guanche) of Canary Island is a discussed element for the origin of local identity as well as the model of the ancient farmer (Mago) is the construction of local “authentic” rural culture. On the other hand, the tourist is the external element, sharing his expectation, built on this particular culture. So, in our particular case, the isolated identity could be possibly defined by these three elements: the connection and the encounter between two different local archetypal dimensions (Guanches and Magos) and one of the external elements (Tourists). Behind this interpretation stands the idea of contact zone: “social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power” (Pratt, M.L., 1991; 23). Therefore, the isolated identity is not a monolithic identity, but a changing relational concept based on the cultural meeting, in a specific context, a social space. We will see that the contact zone is parallel to the heritage management participation arena, a concept based on contradiction (Castaingts, 2004).

The second dimension of the definition of isolated identity is geographical context. The case studied is located in remote region north of Tenerife. In this case we can consider a double distance: one from the most populated areas of the island (metropolitan area of Santa Cruz but also the “Sur”-Las Americas and Los Cristianos) and the other, more general, due to the position of Canary Island…

With the aim to maintain the idea of a relational identity, we can read this sort of island territorial regime, and use the perspective of Minca: “The ‘Island’ regime is indeed an exceptional regime that applies to both tourists and workers, united here by the fact that ‘the Island’ is regulated by extraterritorial rules and codes” (Minca, 2009: 95). We can extend this concept beyond the well-known resorts area and set it on an isolated scenario: a rural area, far from the center and from the touristic enclaves, recently involved in a process of adaptation to the tourism.

In this stage, the cultural identity, defined in terms of contact among local community and tourists, is negotiated in the arena of cultural heritage. The relation between the actors in this arena (residents, tourist and public administration) is necessarily articulated and multidimensional: the results of each specific configuration are uncertain, case by case depending on the difference in the interests of players. Centered on the development opportunity of community-based tourism, Fuller (2012) gives us some useful recommendations to approach the problem: the importance of the definition of community and the distribution of benefit in it, the superficial level of the contact, the different roles, the conflicts between the community and the public actor, the standardization of the cultural heritage.

According to our purpose, it is fundamental the comprehension of the perception of cultural heritage, for each actor. It could indicate to us not only how they interact with cultural assets but also how politics of protection are elaborated. Equally we include the perception of tourists as one more element for this actor in order to present new exploitation formulas.

Castillo (2016) analyzes challenges in the cultural heritage management and identifies three important dimensions: social perception, citizen participation and conflicts. These ideas promote a new approach to the definition of cultural landscape and, most of all, allow the creation of operative guidelines to reorganize the cultural heritage management, involving the gaze (Urry, 1990) and the representation of the tourist.

On the other hand, Pérez, et al. (2018; 2018) includes in his work the perception and social participation in the diagnosis of touristic heritage resources. In this sense, tourism is considered as a generator of global social welfare. For this reason, is strongly recommended to include communities in decision-making on tourism planning, to record citizen’s opinions, values and perceptions, as a fundamental part in the realization of tourist registration and catalogue.

The study is based on an articulated methodology that combines the multidisciplinary perspective of the research team (archaeology, architecture, geographic, sociology and anthropology) with qualitative and quantitative social research techniques. It comprehends focus groups, in-depth interviews to administrators and businessmen and a questionnaire to the local citizens.

The quantitative data presented derives from a survey applied in the months of April and May 2019. The survey collects groups of variables about: local identity, cultural heritage, landscape and tourism. The design of the survey is based on previous results of the qualitative step of the research (focus groups and semi-structured interviews), as well as the synthesis of the multidisciplinary reports of the experts of the research group. The survey is structured in 5 blocks, including the representation of Buenavista, the social participation, the identification and evaluation of heritage and the perception of tourism and resident profile. Within a total of 36 variables, we selected 8 of them to elaborate this paper caused by their relevance for this analysis and its objectives. Due to the double process of population concentration in the city center with extreme territorial dispersion in small rural community, a random and weighted sample by area is used (N=238). The method of data collection was face-to-face, using the paper support.

In the qualitative part of the research, the importance of cultural heritage for the residents of Buenavista del Norte has been detected thanks to the 6 focus groups and 5 in-depth interviews. In the early phases of the project, groups members and interviews informants’ profiles have been selected according to their key roles and knowledge about heritage management. They include technical and administrative staff, members of cultural associations, businessman and politicians. The items on which they worked focused on a definition of the municipality, its main resources, degree of knowledge, importance of tourism activity, conflicts in the use and management of those resources and the population's own attitude towards management of heritage.

Buenavista del Norte is located on the island of Tenerife. A basic analysis of demographical data, provided by INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística) and ISTAC (Instituto Canario de Estadística), allows a selective description of the case studied. Buenavista is a rural municipality, where 4423 people reside in 2018, with a low density of population (71 inhabitants / km², definitely lower than the rest of the Island of Tenerife - 441.75hab./km²), with a balanced distribution by sex. The conformation of the spaces and territory, its location on the Island and the rural character of the municipality (much of the territory occupied by protected natural areas) define many of the characteristics of typical populations of these areas: a progressive loss of residents, a low youth index and an aging pyramid (a large cohort centered between 40 and 59).An interesting fact is the concentration of the population in the area in which the capital of the municipality is located (75.5%), where is situated the economic and administrative activity and where we can find the best infrastructures and connections. The remaining population (24.5%) is distributed in the hamlets of the municipality and the foreign population represents a low percentage (4%) of residents.

Considering socio-economic aspects, we find the very significant issue of the low education level of residents in the municipality: 52% (of the elderly 16 years) does not have completed studies, while the illiteracy rate is similar to that of the rest of the island. Looking at the economic structure, the rise of tertiary sector stands out in employment; even if we consider Buenavista as a “rural” municipality 63% of jobs are in this sector. Employment (41.3%) and unemployment (19.95%) rates reflect general trends of the island.

Regarding the participation of the community, we highlight two traditional mechanisms that will give us a basic idea on actions carried out: the number and type of collective association in the municipality and the electoral participation. According to information provided by the Associations Registry of Canary Autonomic Government, we can safely assume that number of associations is considerable: a total of 70 (consulted on January 2019). Nevertheless, according to the information of the Buenavista’s City Council this number would be slightly lower if we consider association active on the territory and collaboration/union between them (around 60).

These associations are driven by diverse motivations (solidarity, culture, youth, leisure and sport, education and humanitarianism, etc.). They are registered as: sports, neighborhood, parents, educational, artistic and cultural, beneficial, non-governmental organizations, associations of senior citizens, environmental groups, youth, women's collective defense, etc. This fact acquires great importance: considering that Buenavista del Norte is one of the municipalities with the lowest population in the northern region of the island of Tenerife, it shows a large capacity for self-organization and commitment. On the other hand, related to the electoral participation, we present the official results from the database of Spanish Government for the local election and general election of April 2019 (Table 1).

Table 1

Electoral participation April 2019

Electoral Participation |

April 2019 |

|

Local |

General |

|

Buenavista |

71,88% |

70,81% |

S/C de Tenerife |

53,38% |

68,47% |

Spain (mean) |

65,20% |

75,75% |

Source: Own elaboration from data of Gobierno de España

We underline that in Buenavista the electoral participation for the local government is definitely stronger than metropolitan participation (S/C de Tenerife) and higher than the average of Spain. For the general election the participation is sensibly lower than the Spain mean but higher than the metropolitan one.

In this paper, we present the analysis of four groups of variables, related to the perception of residents: identity (1), participation (2), heritage (3) and tourism (4). Results are elaborated from collected surveys and analyzed according to our theoretical framework and to preliminary qualitative part of the research (focus groups and interviews). The descriptive analysis and the discussion will drive us directly to the conceptual and operative conclusions.

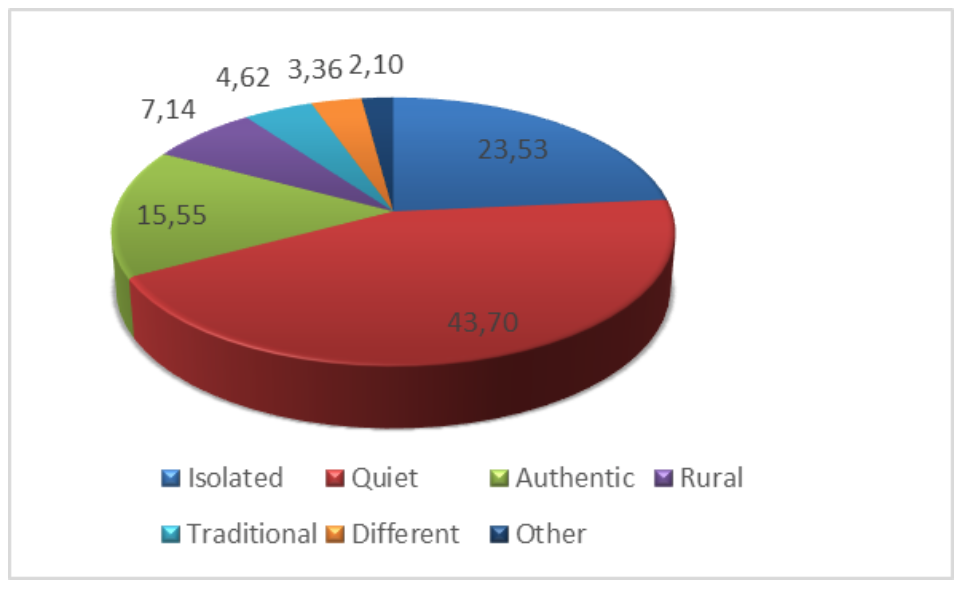

The first group of variables defines the self-perception of identity and helps us to build the concept of isolated identity. In this case we consider 3 variables. These three dimensions voluntarily mix individual elements with contextual and territorial element. First of all, we asked for the definition of the Municipality. If we focus on the adjectives (Fig. 1) chosen by the interviewed, we can affirm that quiet and isolated cover more than 65% of the answers.

Figure 1

Buenavista definition

Source: Own elaboration

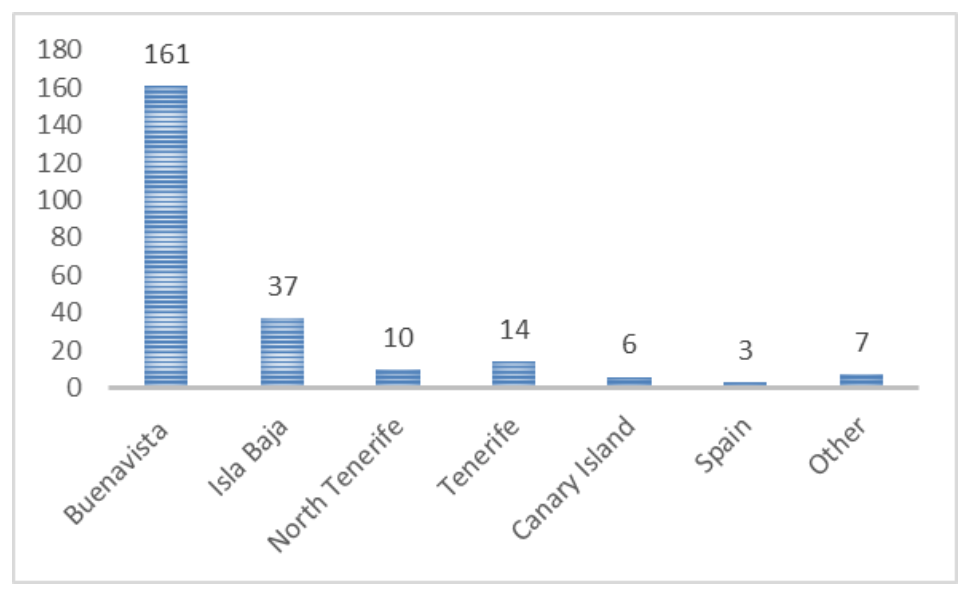

The second variable is related to the sense of belonging of population. The stronger territorial link is the local one: residents, consider themselves “from Buenavista”. The identification with the local dimension at the municipality level is significant in relation to regional context (Tenerife- Canary Islands) and national context (Spain) (Fig.2).

Figure 2

Local Identity

Source: Own elaboration

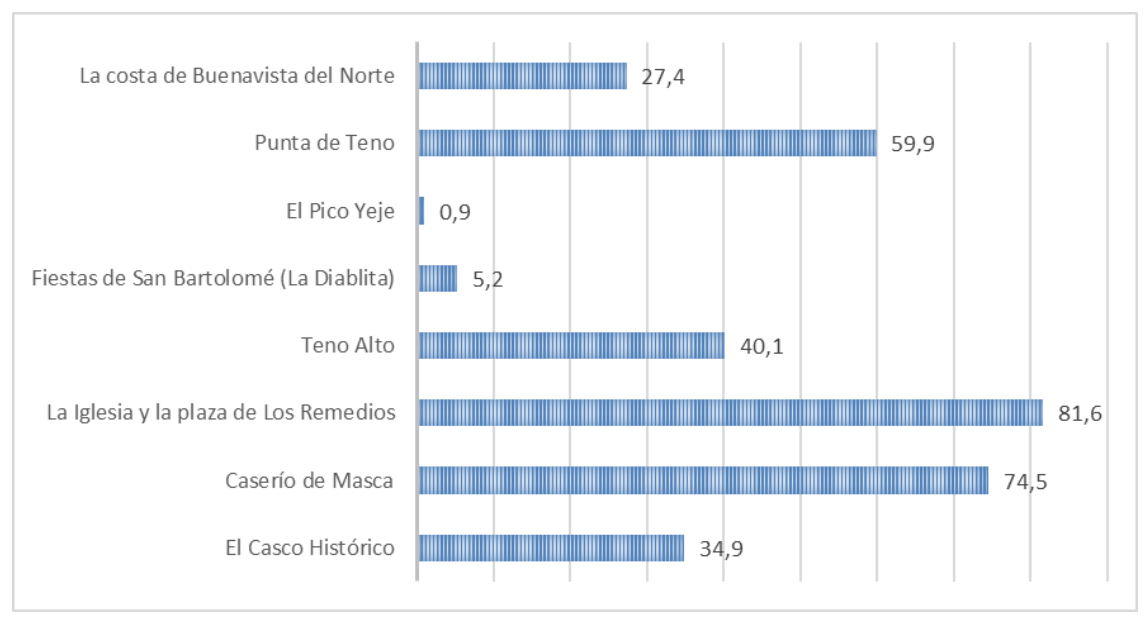

The last variable analyzed for the construction of the meaning of the isolated identity is more tangible: the elements of self-representation. According to the results of the surveys, it indicates that it is the Remedios Square and Church in the historic center, together with sites of Masca, and Punta de Teno, which most represent the municipality (Fig 3.).

Figure 3

Local identity and elements of representation (%)

Source: Own elaboration

We can summarize that it is a strong local identity related to natural and material elements of the landscape (Masca and Teno), based on places, connected to the territory and also with historical heritage (Church and Square). In particular, Masca is one of the “favorite corners” for the residents of Buenavista del Norte (10,7% recognize it as “favorite place”). In order to complete our elaboration about the isolated identity we add two definitions of Buenavista form two in-depth interviews. “Buenavista for me it is the last corner ... we could say where the local environment has kept a little more in its essence… It maintains the essence of mountainous and original Tenerife. Buenavista keeps purer both gastronomic and environmental, and a little more in contact with its essence. Perhaps it’s because the hand of man has not acted so abrasively, as it has been done in other areas.” (Interview DH). “Buenavista for me it is a "mini-paradise" within the paradise that is the island of Tenerife, understanding mini-paradise for everything that surrounds us, both the proximity to the sea that for me is very important, as the proximity to the mountain. Not only the environmental values, but also other values as a society, as people…” (Interview IR).

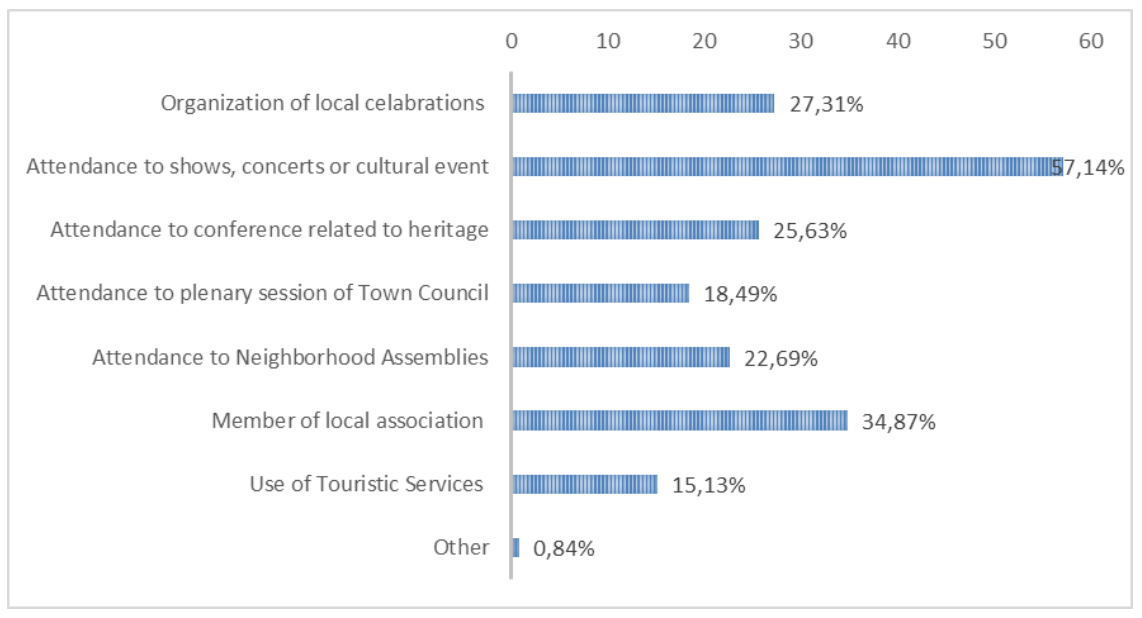

We underlined in the presentation of the case studied the participatory character of residents of Buenavista. Results from our survey confirmed this perspective. Fig.4 shows the participation of citizens to various activities (cultural, social and political).

Figure 4

Participation (last two years)

Source:Own elaboration

Analyzing the actions of participation, it is relevant that, according to our research 35% of resident is member of a local association and about 25% organizes local celebrations and attends conferences related to heritage.

To describe the perception of heritage a double dimension approach is used. The variables considered, in this case, includes both field: conceptual and practical. The conceptual level is described by an association process and evaluation of knowledge of the cultural heritage. In parallel, we propose a set of evaluation about practical and direct issue on cultural heritage, coming to the heritage management.

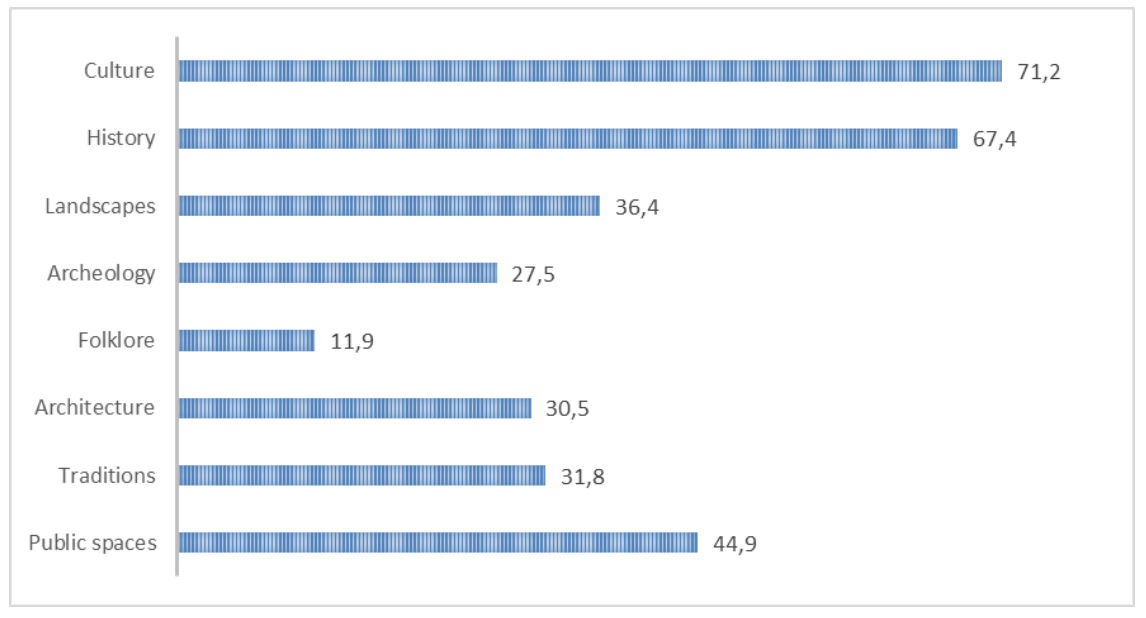

The first dimension investigates the conceptual net of association between the heritage and other perspectives (Fig.5).

Figure 5

What do they associate

cultural heritage with?

Source: Own elaboration

As expected, according to the residents, Culture and History are the two concepts most related to heritage. However, we want to underline two significant dimensions: public spaces (44,9%) and landscape (36, 4%). The second element is clearly related to the rural character of the place and the strong links between populations and territory. Moreover, the importance of public spaces in the concept of heritage is one of the key and, at the same time, conflicting results of our investigation. In order to develop this point, we add the concept of knowledge of cultural heritage (Fig.6).

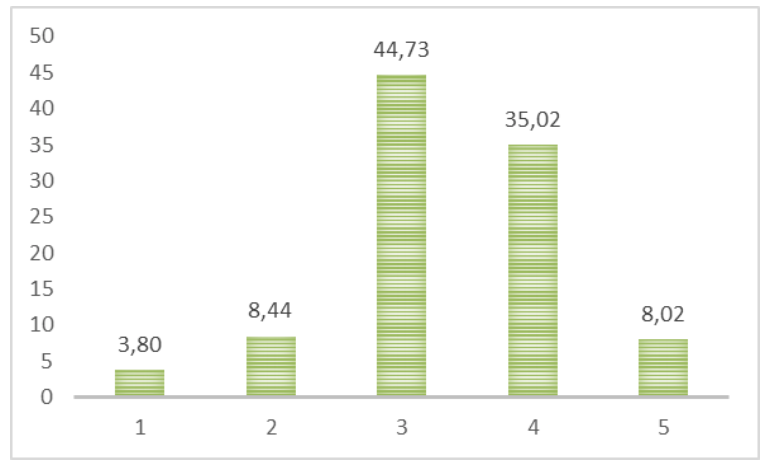

Figure 6

Knowledge of cultural

heritage (Likert scale 1-5).

Source: Own elaboration

The rate of local residents that declare to be able to recognize the cultural heritage is quite high (> 40%, mean 3,34), considering the general social condition of the town (geographically isolated, population aging, low educational level).

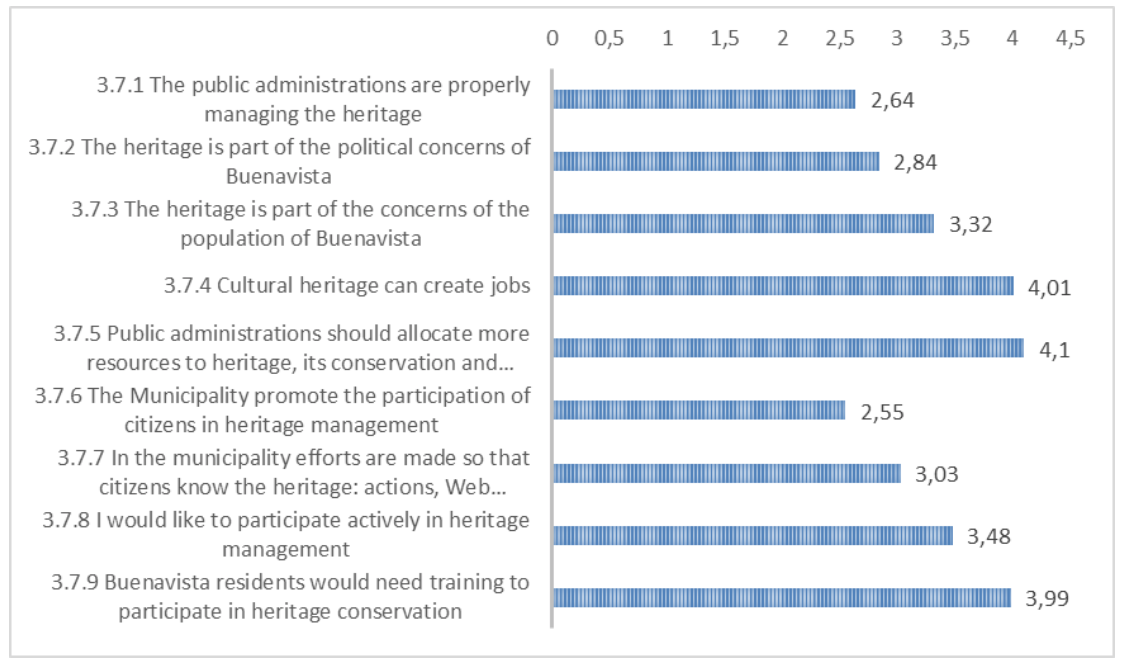

Figure 7

Heritage Knowledge and

Management (Likert scale- means)

Source: Own elaboration

Figure 8 contains interesting information about the idea of heritage’s management. In this case, we have to consider one more element in the context. As far as heritage management is concerned, without any doubt the highest percentage of the population responded that they considered that it should be of a public nature (63.5%) and the rest thinks that it should be mixed (public and private). Nobody declares his preference for a fully private management model. Nevertheless, the idea of public nature is not directly related with the potential of communitarian management. The participatory approach is still quite week compared to other issues like the creation of jobs, and the negative evaluation of public administration or the necessity of investments and resources. Additionally, we want to underline the strong request of training as a requirement for active participation in the conservation of cultural heritage.

The perception of cultural heritage has been discussed in the focus groups and in the in-depth interview. The ideas elaborated in the groups around the management and protection of cultural resources are conflictive. In addition to the identification of main assets, several groups express the lack of knowledge of resources by the great part of residents. On the other hand, a negative perception of the public action for the heritage conservation (confirmed by the quantitative results) is the main thread: together with a sense of nostalgia, the discussion focuses on the lack of economic investments and on the superficial protection of heritage sites by the public administration. In-depth interviews support this vision: “I believe that the older population does know the values we have as a municipality, but the value of the heritage is not being diffused and communicated correctly. I think that it does not happen in the school. Neither the city council acts correctly in this direction. We have a heritage value that sometimes we do not even know ourselves” (Interview IR). An interesting example of a successful union between social participation and heritage management is the organization of local celebrations. The focus group with the old town cultural and musical association is clear: the mobilization to prepare the local celebration is high; the traditional music is one of the elements of this type of collaboration. Nevertheless, these events are mainly direct to residents: created from below (with public support) and joined principally by local population. The possible creation of links with the rising of touristic phenomenon is one of the possible challenges of our case.

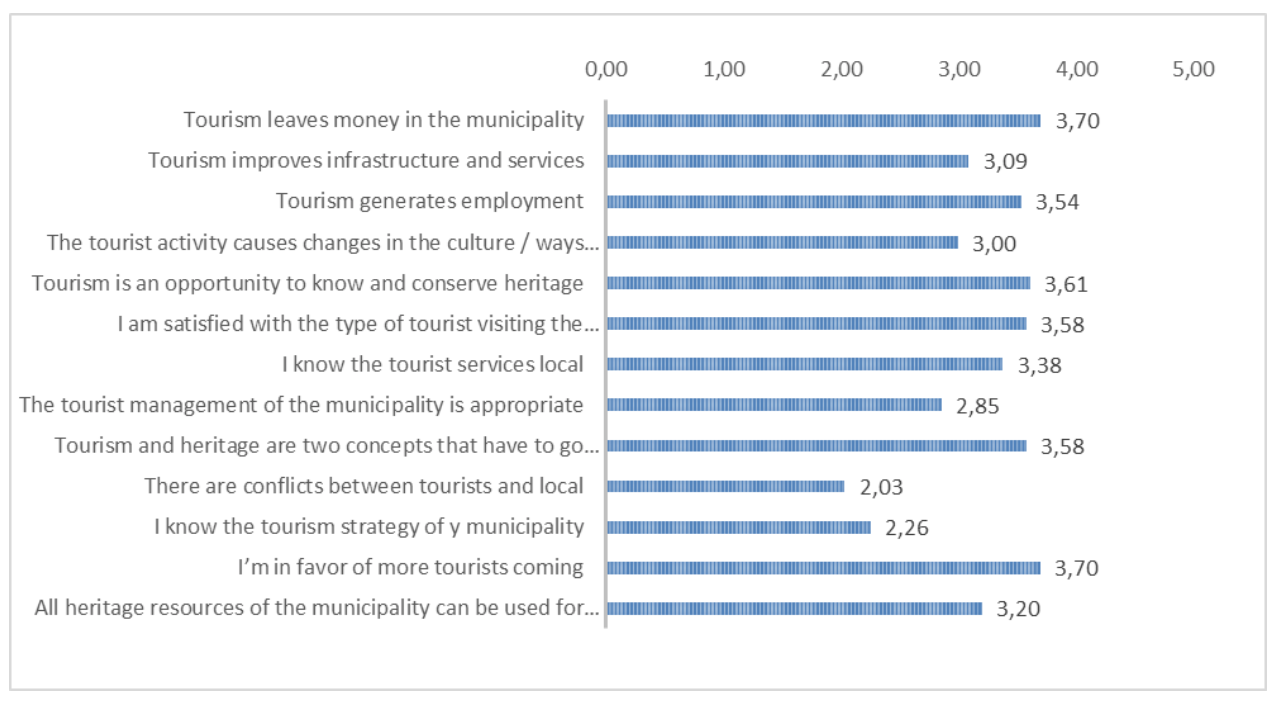

The definition of tourism perception is also presented with a mixed set of response (Fig.8)

Figure 8

Tourism activity perception

Source: Own elaboration

First, we underline that the highest evaluation is for two connected items. Residents of Buenavista think that tourism is an important factor of economic development for the Municipality and, at the same time, wish the touristic phenomenon could increase. In a complementary way, they believe that tourism is an opportunity to know and conserve the heritage and they are quite satisfied with the type of tourist visiting the municipality. Moreover, they declare that conflicts between tourist and residents are limited. In general, they express a positive vision and perception of tourism, for example that they partially agree to make all the resources available for tourists. On the other hand, there are two points clearly incongruent with this perception. First, the management of public administration is not well evaluated by residents. The lack of knowledge about the management strategy of the municipality supports and intensifies this aspect. Secondly, there are some doubts about the impact of tourism on local culture and way of life. Groups and, most of all, in depth interview show and confirm this general idea, and underline the structure of opportunity created by the development of tourism.

Results presented focus on the relationship of the local community with the heritage. In general, we want to highlight several elements of convergence between the feeling of identity and belonging, the participation of the population, the cultural heritage and tourism. At the same time, we observe some divergences and conflicts. This complexity requires a detailed analysis, as well as a specific management plan. In this sense, the results of the study of Buenavista confirm and support the conclusion of Castillo (2019).

Starting from conflictive points, we defined Buenavista as a case of medium-high social participation. At political level we considered the valid electoral affluence, even if probably the most significant issue is the strong net of cultural association that organizes the social participation on the territory. This asset makes possible a continuous structured collective action, beyond the informal encounter of neighbors. Moreover, the collective organized action is strongly connected with the heritage, since great part of associations is cultural related. Even so, we find contrast just in the participation in heritage management: an ambivalent situation is shown. Residents think that management of cultural heritage must be public but, at the same time, they are not sure about the direct participation. They are critical with the actions and choices of public administration but this feeling does not determine direct implication. This basic idea of delegated public management has to be considered as a starting point. This could be a first approach to the building of a confrontation arena for two separate actors: the community and the public administration. The process of transformation of natural and historical resources is traditionally powered by touristic phenomenon (Rodríguez, 2007), opening a particular contact zone. The significance attributed by the community, strongly related to local identity, could generate contrast and conflict with the regulation perspective of the administration. The conservation and protection of natural and historical resources should be the results of the continuous negotiation between bottom-up pressure (community) and top-down decision (administration).

In this context, we considered tourism as an additional and fundamental actor in this arena. Its role goes beyond the amplification of changes in naturals and heritage resources. In this case it is important focus on the perception of tourism by residents. We register a positive and optimistic view, based on material elements as the economic value and the creation of infrastructure and services for resident. Moreover, tourism is considered an opportunity to know and conserve the cultural heritage.

This information is key element for the maintenance and improvement of quality of life of Buenavista’s community. It is essential to integrate these results to preserve their cultural manifestations through learning strategies and accountability acquisition. The perception must be directed towards a real and active participation, with decision power actors. Both tools, perception and participation, should be included in the tourism planning processes. This way of understanding, registering and managing tourist resources, can bring light to that complex arena that is the Municipality of Buenavista del Norte. Otherwise, the impacts of moving towards a service economy, based on tourism activity, would extend impacts of rapid and intense tourism development, affecting the capacity of the destination and the contact between locals and tourists. Although in this work the positive predisposition of the Buenavista community to “transfer” all its resources for tourism has been detected, we cannot rule out the affirmation of schemes prevalent in other areas of the island and based exclusively on the economic and foreign vision.

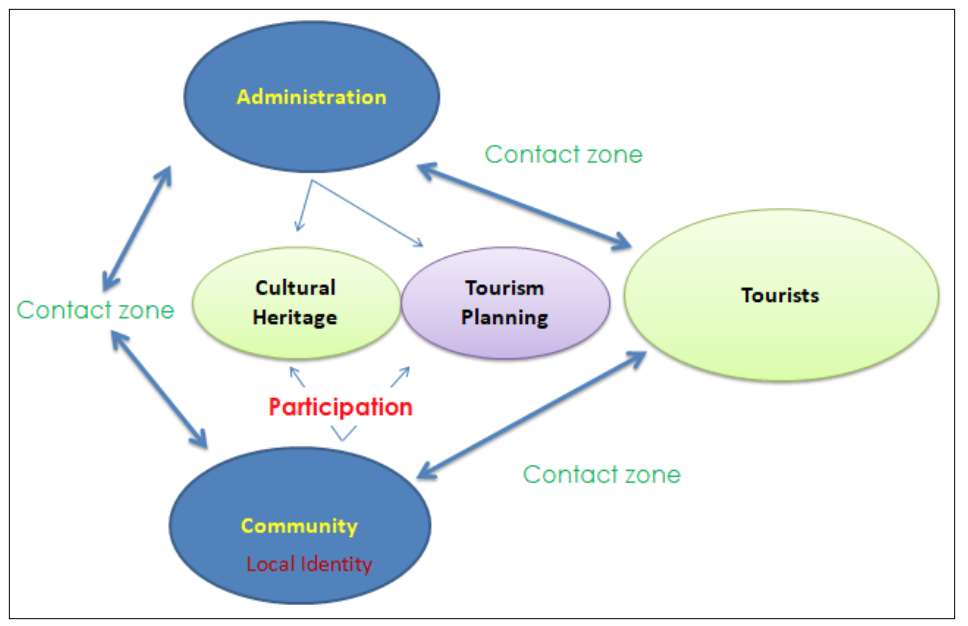

In this sense, the arrival of tourists has reconfigured relations between community and administration in the cultural heritage management arena. First, it creates a new cultural contact zone among residents and administration. Tourist, as a third actor, has got a particular culture, a particular motivation and a particular representation of natural landscape and historical-traditional resources. Instead of questioning about the correspondence between the external, touristic, gaze and the local self-representation of the community, we propose assume the dynamic of the relation and its consequence on the local identity. Secondly, the heritage perception and definition represent an element of materialization of the cultural contact zone. Then, the isolated identity is not something static and monolithic, since the island is well connected with international culture and differences: tourism redefines local identity in a continuous process. At more practical level it reconfigures also the structure of opportunity of heritage management. The arena of Buenavista is complex a three-actor arena, where zones of contact lay on a particular isolate and, at the same time, participative identity (Fig.9).

Figure 9

Buenavista’s Arena

Source: Own elaboration

The balance of this new structure is also defining a new idea of cultural landscape. In fact, this idea is based on guidelines of the European Landscape Convention of Florence (2000) where landscape is recognized as “an essential component of people’s surroundings, an expression of the diversity of their shared cultural and natural heritage, and a foundation of their identity.” (Council of Europe, 2000).

According to this approach, it is evident that we can’t apply participation ready-made plans or leave the complete self-organization to the community. On the contrary, we must analyze specific aspects of the identity and social perception, as shown in the case of Buenavista. One of the central points is the collective re-elaboration of the idea of public. Would be possible for the changing isolated identity overcome the conflict between direct participation and delegation, just in the management of this material and immaterial elements of this cultural identity?

In this paper we presented an analysis based on a particular point of view about the relation between local identity, cultural heritage and tourism. The case studied, Buenavista del Norte, is inserted in a large tradition of studies that focus on participation. In Spanish context, this research field has been increasingly studied (Castillo y Querol, 2014; Castillo et. al, 2016; Castillo, 2016; Castillo, 2019). In the theoretical framework we introduce the dimension of the local identity, defined as isolated identity. We saw that the concept of island in this sense is dynamic and relational, more than exclusive. The island is the territory of connections, the contact zone for different cultures. The aim of this paper was analyzing the relation among local identity and heritage, as well as the new configuration determined by the growth of the flow of tourists. Beyond this general aim, we consider the social participation to heritage definition and management as a central point of new governance of cultural resources. In this case we spoke about a multi-actor governance process to identify the differences between community, public administration and tourists. The concrete and practical concept of arena expresses the territory where different interests and perspectives take place and connect themselves. In this sense, heritage resources (material and immaterial) represent the concrete in each practical case, the contact zone between different cultures, further than economic value.

According to the presentation of the results and its discussion we can summarize conclusions in the following points:

Finally, a specific work on the tourist point of view of this area, including expectative and motivation, will be the next step of our research project, with the aim of the elaboration of a specific plan for the activation of the local participation in heritage. This is a clear opportunity to break the identitary cage and re-configure the significance of isolated identity.

Castaingts, J. (2004). Los mercados como campos y arenas. Hacia una etnoeconomía de los procesos mercantiles. Alteridades, 14(28), 109-125.

Castillo, A. (2019); Participative processes in cultural heritage management. Methodology and critical results bases on experiences within the Spanish World Heritage context. PCA European Journal of Postclassical archaeologies, V.9, pp.61-7.

Castillo, A. (2016). Relaciones entre ciudadanía y agentes patrimoniales desde la perspectiva de la investigación académica: retos pendientes en la gestión del patrimonio cultural. PH: Boletín del Instituto Andaluz del Patrimonio Histórico, 24(90), 205-207.

Castillo, A. y Querol, M.A. (2014): Archaeological Dimension of World Heritage: From Prevention to SocialImplications. Castillo (ed.). Archaeological Dimensionof World Heritage: From Prevention to Social Implications.New York: Springer-Verlag, 2014, pp. 1-11 (SpringerBriefs inArchaeological Heritage Management).

Consejo de Europa (2000): Convenio Europeo del Paisaje. Florencia, 2000.

Estévez, F. (2011) “Guanches, magos, turistas e inmigrantes. Canarios en la jaula identitaria”. Atlántida: Revista Canaria de Ciencias Sociales (3), pp. 145-172.

Fuller, N. (2012) “Turismo sostenible, desarrollo y patrimonio cultural. El caso de las comunidades campesinas e indígenas del Perú” in TALAVERA, A. S., DARIAS, A. J. R., & RODRÍGUEZ, P. D. Responsabilidad y Turismo.PASOS, Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural: Asociación Canaria de Antropología

Marradi, A. (1980). Concetti e metodo per la ricercasociale. Firenze: La giuntina.

Mata Olmo, R. (2012). Retorno al paisaje mediterráneo. Cultura territorial, conflictos y políticas. En: Geografía: retos ambientales y territoriales: conferencias, ponencias, relatorías, mesas redondas: XXII Congreso de Geógrafos Españoles, Universidad de Alicante, 2011 / Vicente Gozálvez Pérez, Juan Antonio Marco Molina (eds.). Madrid: Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 2012. ISBN 978-84-938551-8-5, pp. 17-65

Minca, C. (2009). “The Island, Work, Tourism and the Biopolitical”. Tourist Studies. 9 (2). pp. 88-108.

Navajas Corral, Ó., & Fernández Fernández, J. (2019). La gestión patrimonial desde la responsabilidad social. Pasos: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, Vol. 17, Nº. 2, 2019, págs. 285-298

Pérez, E., Cupiche, V., Medina, C. y García, C. (2018): Cultural tourism management strategies: the social and cultural perception of the local population of the Mayan communities of Tihosuco and Sacalaca in Yucatan (Mexico). Conference ICAHM AnnualMeeting,October, 2018, Sicily. DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.28570.08646

Pérez, E., García, C., Medina, C., Cupiche, V. (2018): Las comunidades: agentes turísticos clave para la conservación del patrimonio cultural. Ciencia y Desarrollo, nº294. México

Pratt, M. L. (1991). Arts of the contact zone. Profession.

Rodríguez Darias, A. J. (2007): “Desarrollo, gestión de áreas protegidas y población local. El Parque Rural de Anaga (Tenerife, España)”. Pasos, Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 5 (1): pp. 17-29.

Urry, J. (1990): The Tourist Gaze. Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. Sage Publications, London, Newbury Park, New Delhi.

1. Assistant Professor. Universidad Europea en Canarias. david.stendardi@universidadeuropea.es

2. Associate Professor. Universidad Europea en Canarias. elenamaria.perez@universidadeuropea.es

3. Associate Professor. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. alicia.castillo@ghis.ucm.es

4. Assistant Professor. Universidad de La Laguna. jisraelgc@gmail.com

[Índice]

revistaespacios.com

Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons

Reconocimiento-NoComercial 4.0 Internacional