Vol. 41 (Issue 17) Year 2020. Page 23

TORRES-BARRETO, Martha L. 1; ALVAREZ-MELGAREJO, Mileidy 2; MONTEALEGRE BUSTOS, Felipe 3

Received: 30/01/2020 • Approved: 05/05/2020 • Published 14/5/2020

ABSTRACT: This research evaluates the relationship between tangible resources and companies´ potential absorptive capabilities using data of 2,093 Colombian industrial firms through econometric models that allowed us to contrast linear regressions and Logit models. The results suggest that financial and human resource characteristics of firms, positively influence their ability to acquire and assimilate knowledge derived from the environment. Likewise, firm´s ability to cooperate and interact with their ecosystem has a positive influence on their potential absorptive capability. |

RESUMEN: Esta investigación evalúa la relación entre los recursos tangibles y la capacidad de absorción potencial de las empresas, utilizando datos de 2.093 empresas industriales colombianas a través de modelos econométricos que permitieron contrastar regresiones lineales y modelos Logit. Los resultados sugieren que las características financieras y los recursos humanos de las empresas influyen positivamente en su capacidad de adquirir y asimilar el conocimiento externo. Asimismo, la capacidad de la empresa para cooperar e interactuar con su ecosistema tiene una influencia positiva en su capacidad de absorción potencial. |

In recent decades, enormous efforts have been made to study the source of competitive advantages of firms and the differences in business performance between organizations that belong to the same field and have similar characteristics. One school of thought related to modern administration: The Theory of Resources and Capabilities (TRC), states that certain capabilities act as a source of sustainable competitive advantages, these have been labeled as dynamic capabilities. They are composed by organizational processes and routines that allow firms to adapt to changes in the environment, to transform their set of resources and capabilities, and develop competitive advantages (Fosfuri & Tribó, 2008; Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997). One of these dynamic capabilities is known as the absorptive capability (AC). This is a pioneer capability in creating competitive advantages, especially when firms maneuver in a dynamic environment (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Cruz, López, & Martín, 2009; Jansen, van den Bosch, & Volberda, 2005; Olea-Miranda, Contreras, & Barcelo, 2016; Wang & Ahmed, 2007; Zahra & George, 2002).

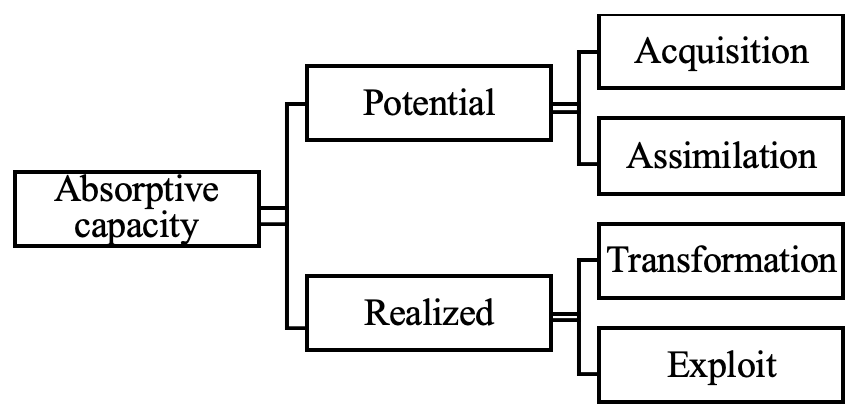

The concept of absorptive capabilities (AC), was originated in the 1990s (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990), and was later characterized as the integration of two subsets of capabilities: potential absorptive capability (PAC) and realized absorptive capability (RAC) (Zahra & George, 2002). The first one regards the firm´s ability to acquire and assimilate external knowledge, while the second one defines the firm´s ability to transform and exploit new knowledge. This has been further improved by various studies that delve into the importance of these types of AC and the competitive benefits firms obtain when they manage to develop the already mentioned capabilities (Jansen et al., 2005). Up to know, the research on these capabilities has been focused on the analysis of various organizational phenomena that they may cause (Fosfuri & Tribó, 2008; Vega-Jurado, Gutiérrez-Gracia, & Fernández-De-Lucio, 2008); regardless of the origins or the elements that create these capabilities. The showcases in the literature suggest that the determinants of absorptive capabilities may be identified with organizational learning (Zahra & George, 2002), or with organizational structures (Van den Bosch, Volberda, & De Boer, 1999), or may be atributed to a combination of capabilities (Garzón-castrillón, 2016; Jansen et al., 2005), and human resources (Dyer & Singh, 1998; Garzón-castrillón, 2016; Minbaeva, Pedersen, Björkman, Fey, & Park, 2003). However, few studies attempt to find a relationship between firm´s resources and their absorptive capabilities. This research aims to evaluate the existence of a dependency between tangible resources, and the firm’s potential to acquire and assimilate information from the environment.

This document is organized as follows; section two presents the theoretical framework on resources, dynamic capabilities and, in particular, absorptive capability, along with proposed hypotheses. In the third section we described the methodology used to test the hypotheses; section four shows the results obtained by contrasting the econometric models, and finally, in section five the conclusions of the research are presented.

Dynamic Capabilities (DC) arise as a complement of the TRC, in order to explain the paradigm of competitive advantages developed by firms, while operating in changing and unpredictable environments (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). The first theoretical conceptions of the term are attributed to the work of Teece & Pisano (1994) and Teece et al. (1997). Since that time, they have been addressed by different academics whom agree on their definition as a set of specific, identifiable, strategic and organizational processes that facilitate the development of products and alliances, as well as strategic decision making made by organizations, in order to adapt to the dynamic nature of their environment, and thus, achieve new competitive advantages (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Miranda, 2015; Teece et al., 1997).

DC have been the object of diverse characterizations, such as the ability to innovate (Ambrosini, Bowman, & Collier, 2009; Danneels, 2002; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Torres-Barreto, 2017), the ability to cooperate with other organizations (Escandón, Rodriguez, & Hernández, 2013; Kale & Singh, 2007), the ability to autonomously reconfigure the firm (Ambrosini & Bowman, 2009; Masteika, 2015; Teece, 2007), the marketing capability (Bruni & Verona, 2009; Danneels, 2002), the ability to perform R&D activities (Helfat, 1997; Helfat & Peteraf, 2003; Zollo & Winter, 2002), and the absorptive capability itself (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Lane, Salk, & Lyles, 2001; Zahra & George, 2002). Nevertheless, these characterizations have something in common: they identify a relationship between dynamic capabilities and business performance, or between the DC and the development of a competitive advantage; which indicates their relevance for the industry.

The term Absorptive Capability (AC) has its origins in macroeconomics, as the ability to use resources and external information for its own benefit (Alder, 1965; Garzón-Castrillón, 2016; Murovec & Prodan, 2009). The AC concept applied to organizations was first addressed by Cohen & Levinthal (1990), who defined it as the firm´s ability to identify, assimilate and apply external knowledge for commercial purposes. Based on this work, theoretical and empirical research that deepen its understanding and identification as a source of competitive advantages is found (Camisón & Forés, 2014; Fosfuri & Tribó, 2008). This reveal absorptive capability (AC) as the firm´s ability to acquire, assimilate, transform and exploit external knowledge.

Based on the aforementioned description, some AC typologies have been created, one of the most accepted divides them into: potential and realized absorptive capabilities (Zahra & George, 2002), as shown in Figure 1. Potential absorptive capability (PAC) refers to the renewal of the firm’s knowledge base and includes the necessary strategic skills used by organizations to adapt and evolve in dynamic environments (Peris, Mestre, & Palao, 2011), as well as anticipating changes in the environment. A firm that develops this capability is prone to generate strategic advantages (Jansen et al., 2005; Zahra & George, 2002), and it has the differential potential to: (1) acquire external knowledge, meaning, to locate, identify, assess, select and acquire relevant knowledge that is externally generated (Camisón & Forés, 2010; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Lane & Lubatkin, 1998; Liao, Welsch & Stoica, 2003; Zahra & George, 2002), (2) assimilate this knowledge, meaning, processes or routines that allow for analyzing, processing, interpreting, understanding, internalizing and classifying the external knowledge acquired (Camisón & Forés, 2010; Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Zahra & George, 2002).

Notwithstanding, in order to exploit and apply the knowledge generated through the potential absorptive capability, a realized absorptive capability (RAC) is required, which includes the transformation and exploitation of knowledge. The firms that manage to develop the "realized" instance reflect efficiency in taking advantage of external knowledge (Fosfuri & Tribó, 2008) and perceive the consequences over their business results (Peris et al., 2011).

Figure 1

Typologies of the Absorptive Capability

Source: Based on the model proposed by Zahra & George (2002)

Tangible resources are specific assets of a tangible nature that a firm owns and uses to carry out its economic activity and compete within the market. It is widely recognized that tangible resources alone do not generate competitive advantages (Barney, 1991); however, they can generate higher rents when the owned property is distinctive or physically unique, and when it cannot be transferred because it is essential to the firm (Herzog, 2001). Tangible resources are necessary within the context in which firms perform their activities and are relevant factors in generating routines and capabilities (D’Adderio, 2011), taking into account that the latter are generated via interaction between the set of resources that firms have and the capabilities they have developed (Alvarez-Melgarejo & Torres-Barreto, 2018c; Amit & Schoemaker, 1993; Zahra, Sapienza, & Davidsson, 2006). The insufficient attention that tangible resources receive may be due precisely to the postulates of the TRC, which states that sustainable competitive advantages are more likely to be based on intangible resources, given that they are more difficult to imitate and substitute by competitors (Barney, 1991; Dierickx & Cool, 1989; Peteraf, 1993; Torres-Barreto & Antolinez, 2017). However, the study of the effects of tangible resources on the generation of capabilities that can lead to competitive advantages is a field of interest for academia and the business world (Schriber & Löstedt, 2015) and has been little explored according to the work of Alvarez-Melgarejo & Torres-Barreto (2018a), where they carry out an analysis of research trends on the relationships between resources and the capabilities of companies.

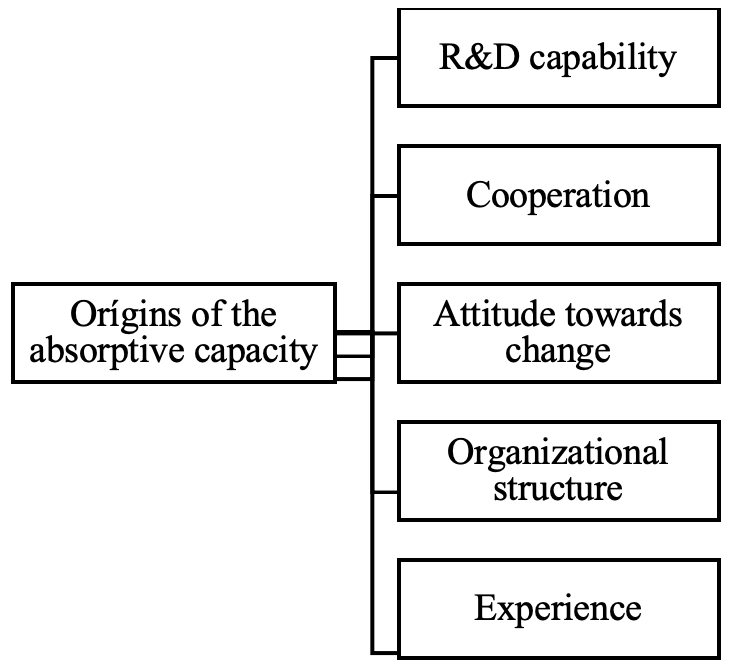

The research regarding absorptive capabilities has been focused in their impact on organizational processes (García-Morales, Ruiz-Moreno, & Llorens-Montes, 2007; Leal-Rodríguez, Roldán, Leal-Millán, & Ariza-Montes, 2014; Nieto & Quevedo, 2005; Tu, Vonderembse, Ragu-Nathan, & Sharkey, 2006); but less attention have been paid to the way in which these capabilities are created and developed. Some studies focus on the ability to perform R&D activities as a source of absorptive capability (see Figure 2), in the ability to cooperate with other organizations within the environment and on the attitude of the firm towards change (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; Murovec & Prodan, 2009). Another set of studies analyzed the relationship between the organizational structure of the firm and the combinatorial capabilities (organizations’ ability to integrate, configure, combine, synthesize and apply knowledge) (Van den Bosch et al., 1999). An additional source of study considers the acquisition of external knowledge and the experience of the firm as the origins of this capability. Jansen et al. (2005) identify the coordination capabilities as the background of the PAC, and the socialization capabilities as determinants of the RAC. Ebers & Maurer (2014) focus on studying the external and internal relations among the members of a project and the training they receive, as the origins of absorptive capabilities.

Figure 2

Origins of the absorptive capability

Source: The authors

Nevertheless, the literature evidences that potential absorptive capability (PAC) and realized absorptive capability (RAC) are two different types of absorptive capabilities, which may have different backgrounds. The first one links the firm with its environment, and the second one operates within the organization (Fosfuri & Tribó, 2008).

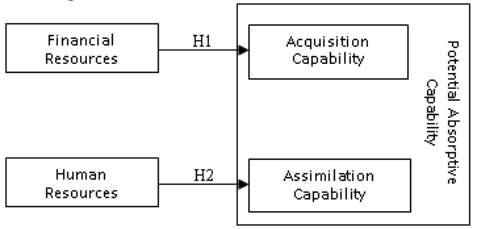

Considering the literature gap, this research proposes that tangible resources may generate potential absorptive capabilities. Within this context, financial and human resources are conclusively analyzed. The reason is that the first ones influence the ability of a firm to acquire information from the environment, by determining the level of investment perceived in acquiring and assimilating knowledge (Forés & Camison, 2008). Firms with greater financial resource capabilities are better positioned to decide on investments related to the acquisition of external information through private contracts, licenses, advisory and specialized counseling regarding topics of interest for the organization; meanwhile firms with less financial resource availability are limited in their interaction with the environment given that they have limited access to payment information services. Having all this into account, we propose that:

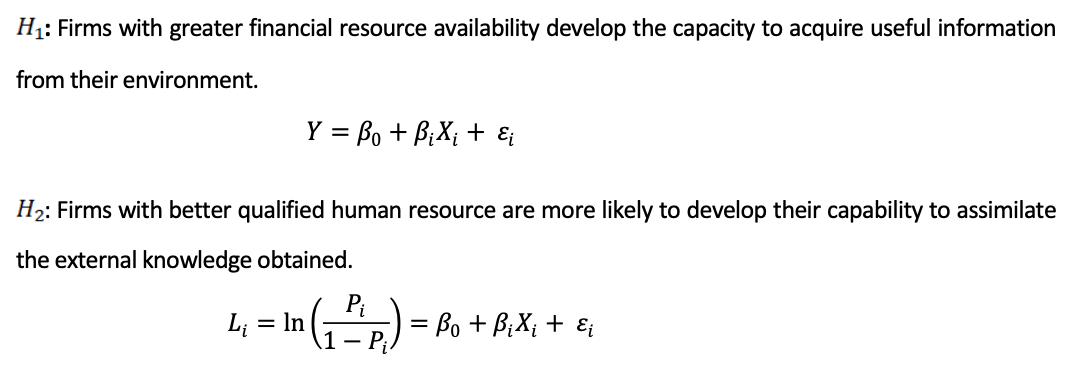

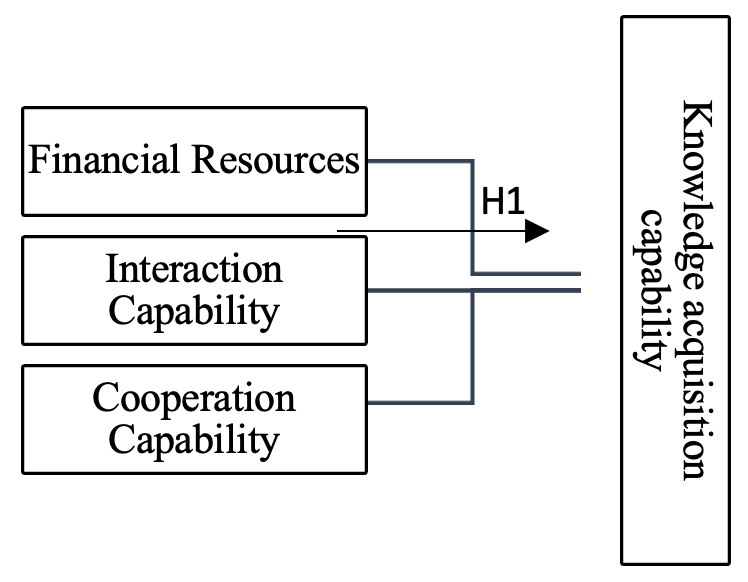

H1: Firms with greater financial resource availability develop their capability to acquire useful information from their environment.

On the other hand, this research analyzes an additional dimension of the potential absorptive capability: The assimilation capability. This assimilation occurs following the acquisition considered in Hypothesis 1. The assimilation consists of appropriating the acquired information and integrating it into the organizational structure. It differs from the acquisition capability because not only information is acquired using financial resources, but it is also integrated into routines or organizational practices, through the use of firm’s human resources. Human resources constitute the firm’s knowledge base and it allows the firms to get information from their environment and to assimilate and interpret it. Therefore, the level of training of the organization’s members can be decisive in the assimilation process of the information acquired. For this reason, it is proposed that:

H2: Firms with better qualified human resource are more likely to develop their capability to assimilate the external knowledge obtained.

The entire research construct is presented in Figure 3

Figure 3

Theoretical construct of the research

Source: The authors

The data used in this research is taken from the Colombian Development and Technological Innovation Survey - Manufacturing Sector (EDIT Industry VII) (DANE, 2015). It is carried out biannually by the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE), which collects information on 589 variables for 8,835 firms (DANE, 2015). The statistical operation is a census. The inclusion parameter is: industrial firms with registered establishments and 10 or more employees. The survey includes investment trends in R&D. DANE guarantees the internal consistency of the data through established control and coverage procedures (DANE, 2017).

The selection of variables was carried out in a two-stage process. In the first one, 141 candidate variables were identified for tangible resources and potential absorptive capabilities. In the second stage, and after a process of review by experts, variables with small contributions to the research were excluded. And we selected a cross-sectional set of data for the year 2014, which includes 55 variables and 2.093 firms (DANE, 2015, 2017).

Previous research suggests that a valid and definitive measure that incorporates the different dimensions of the AC has not yet emerged (Flatten, Engelen, Zahra, & Brettel, 2011; Wang & Ahmed, 2007), as of today the appropriate scales for AC are not yet available (Lane & Lubatkin, 1998; Liao et al., 2003; Mowery & Oxley, 1995; Van den Bosch, Van Wijk, & Volberda, 2003; Zahra & George, 2002), this research identified two proxy variables related to the ability to acquire and assimilate knowledge.

The ability to acquire knowledge was measured using the proxie: "investment made by firms in transfer of technology and knowledge acquisition" (IAC), given that it represents the firm’s efforts to identify and acquire new external knowledge (López, Mejía, & Schmal, 2006; Peris et al., 2011), this allows for firms to adapt to the environment and preserve their competitive advantage (González Campo & Hurtado Ayala, 2014).

On the other hand, the ability to assimilate knowledge was measured using the proxie variable: "relation of firms with intermediaries of the National System of Science, Technology and Innovation" (RCTI). This variable represents the skills firms use to obtain and analyze information from external institutions; this becomes a good path to link new knowledge to existing knowledge (González Campo & Hurtado Ayala, 2014; Peris et al., 2011).

According to Figure 3, two types of tangible resources (financial and human) were included. Financial resources were measured through the use of sales and total investment in science, technology, and innovation activities (ICTI). These variables represent the money that each firm has available for investment (Barney & Arikan, 2001; Blázquez & Mondino, 2012; Galbreath, 2005; Ismail, Rose, Uli, & Abdullah, 2012; McKelvie & Davidsson, 2009; Sáez de Viteri Arranz, 2000). Human resource was measured through the quantity of qualified personnel working for the firm. Its tangible characteristic is based on the literature (Blázquez & Mondino, 2012; Ismail et al., 2012; Rangone, 1999; Sáez de Viteri Arranz, 2000). This resource has been considered a key aspect in the achievement of capabilities and also in sustaining competitive advantages (Nieves & Haller, 2013).

On the other hand, and considering that some capabilities represent a power link that influences the absorption of new knowledge (Todorova & Durisin, 2007); the firm´s ability to cooperate with suppliers (COOPROV), Technological Development Centers (COOPCDT), and Technology Parks (COOPARTEC) were included as independent variables, alongside the capacity to interact with the Superintendence of Industry and Commerce (RSIC), Ministries (RMINISTER) and the National Department of Intellectual Property Rights (RDNDA).

Within the equations, variables such as the size of the firm (TTEMPLEADOS) were included, dummy variables were also created for each industrial sector.

A correlation analysis between the study variables (dependent and independent) will be carried out, in order to determine the existence of linear relationships between the variables and thus reduce the possibility of the presence of multicollinearity in the models to be estimated, which are evaluated with a significance level of 5% (Gujarati & Porter, 2009; Montero Granados, 2016). Subsequently, and considering the characteristics of the independent variables in the two hypotheses raised in the research, a multiple linear regression model will be estimated for H1 and a probabilistic model for H1 (Gujarati & Porter, 2009).

H1: Firms with greater financial resource availability develop the capacity to acquire useful information from their environment.

Figure 4

Specific construct for H1

Source: The authors

The figure 4 presents the construct for this hypothesis and Table 1 presents the analysis of the correlations between the variables included in . In addition to financial resources and absorptive capability, some capabilities related to cooperation and the firm´s affinity with the environment are also considered here, given that the acquisition capability is determined by the extent to which the firm interacts with its own environment. There is a positive and significant association between the investment in technology transfer and knowledge acquisition, as well as SALES (0.70); this is coherent if one takes into account that having economic resources is a requirement to invest, If you square the Pearson coefficient and multiplied by 100 to estimate the bivariate correlation coefficient, it is obtained for SALES (0.702 x 100 = 49%). This means that sales explain 49% of the variability of the investment in technology transfer and knowledge acquisition, while TTEMPLEADOS (0.5622 x 100 = 32%) explains 32% of the variability of the dependent variable. It can be seen from Table 1 that all the independent variables have significant Person correlation coefficients, which will be taken into account below for the estimation of the multiple linear models and tests will be carried out to avoid the problem of multicollinearity.

Table 1

Pearson´s correlation for H1

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

|

1. IAC |

1 |

||||||||

2. SALES |

0.70* |

1 |

|||||||

3. RSIC |

-0.18 |

0.12* |

1 |

||||||

4. RDNDA |

0.09 |

0.20* |

0.37* |

1 |

|||||

5. RMINISTER |

0.09 |

0.14* |

0.45* |

0.29* |

1 |

||||

6. COOPROV |

0.19 |

0.05* |

0.20* |

0.16* |

0.21* |

1 |

|||

7. COOPCDT |

0.14 |

0.16* |

0.18* |

0.22* |

0.25* |

0.21* |

1 |

||

8. COOPARTEC |

0.114 |

0.039 |

0.068* |

0.09* |

0.14* |

0.13* |

0.33* |

1 |

|

9. TTEMPLEADOS |

0.562* |

0.513* |

0.177* |

0.22* |

0.22* |

0.20* |

0.20* |

0.12* |

1 |

Note: * significant correlations at 5%

For the contrast of a multiple linear regression with non-standardized coefficients (Montero Granados, 2016) and robust standard errors (Montero Granados, 2016) was used, their results are presented in Table 2. Initially, a linear model was established in Column 1 with only the financial resources, and its coefficient is significant at 0.001. This corroborates those that are identical in Table 1, this model also reflects an R2 of 0.58, that is, the independent variables explain 58% of the behaviour of the dependent variable (IAC). In Column 2 a model was estimated only with variables of the relational capacities, in this model the coefficients of the variables RSIC, TTEMPLEADOS, with a level of significance of 0.10 are significant and the R2 of this model is 0.48 lower than that obtained in the previous model.

Similarly, a model was estimated in Column 3 only with the cooperation capacities variables, in this the only variable that is significant is TTEMPLEADOS, but its value is zero, therefore, it has no impact on the model, the R2 is 0.38, lower than the model 1 and 2. Finally, in Column 4, a model with all the variables of construct is estimated, to do this, the variable SALE is transformed into a natural logarithm to approach a normal distribution, homogenize the database, reduce heteroscedasticity and asymmetry, and make the estimates more robust (Gujarati & Porter, 2009; Mukaka, 2012), this model obtained an R2 of 0.72, higher than those obtained in the three previous models and this means that the independent variables explain 72% of the behavior of the dependent variable (IAC) (Gujarati & Porter, 2009); in addition, the great majority of the coefficients of the dependent variables are significant from a level of significance of 0.10 to 0.001 and only two are not significant, those of the variables TTEMPLEADOS and COOPRO, which reflects the fact that these variables have no incidence on the behaviour of the IAC.

Table 2

Multiple lineal regression results for H1

IAC |

1. Financial Results |

2. Interaction Capability |

3. Cooperation Capability |

4. Joint capabilities |

SALES |

0.82*** |

|

|

0.74*** |

RSIC |

|

-1.42* |

|

-1.55*** |

RDNDA |

|

-1.70 |

|

-4.04** |

RMINISTER |

|

0.93 |

|

0.94* |

COOPROV |

|

|

0.54 |

0.49 |

COOPCDT |

|

|

0.02 |

2.48** |

COOPARTEC |

|

|

-0.10 |

-3.98** |

TTEMPLEADOS |

-0.00 |

0.00* |

0.00* |

0.00 |

CONST. |

-3.27 |

9.36*** |

9.02*** |

-2.23 |

PROB > F |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

R-SQUARED |

0.58 |

0.45 |

0.38 |

0.72 |

N. |

54 |

54 |

54 |

54 |

+p<0.10 * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Therefore, the model of column 4 (See Table 2) is the one that best explains the knowledge acquisition capability (R2=0.72) and this is presented in Table 3. The calculation regarding the variance inflation factor (VIF) confirmed the absence of multicollinearity with a VIF average=2.23, which is well below the accepted maximum = 10 (Jansen et al., 2005; Neter, Wasserman, & Kutner, 1990). The White test with a p-value=0.162 allows for the heteroscedasticity hypothesis to be rejected heteroscedasticidad; which confirms that the model specification is the most suitable (Gujarati & Porter, 2009; Mukaka, 2012).

Table 3

Model for H1

IAC |

Coef |

p-Value |

SALES |

0.74 (0.13) |

0.00

|

RSIC |

-1.55 (0.34) |

0.000

|

RDNDA |

-4.04 (1.43) |

0.01

|

RMINISTER |

0.94 (0.39) |

0.02

|

COOPROV |

0.49 (0.36) |

0.19

|

COOPCDT |

2.48 (0.78) |

0.00

|

COOPARTEC |

-3.98 (1.29) |

0.00

|

TTEMPLEADOS |

0.00 (0.00) |

0.52

|

CONST. |

-2.23 (2.01) |

0.28

|

PROB > F |

0.00 |

|

R-SQUARED |

0.72 |

|

N. |

54 |

|

Note: Standard errors in parentheses

In table 3, it can be observed that the variables with a positive impact on the TSI are SALES, RMINSTER, COOPROV, COOPCDT, therefore, as sales increase, the capabilities to relate to the Ministries, the capability of the firm to cooperate with suppliers and with the technology development centres, the investment that the firms make in technology transfer and knowledge acquisition (IAC) increase as well. Meanwhile, as the capability to interact with the Superintendence of Industry and Commerce (RSIC) and the National Department of Copyright (RDNDA) and Technology Parks (COOPARTEC) increases, the investment of enterprises in technology transfer and knowledge acquisition (IAC) decreases.

H2: Firms with better qualified human resource are more likely to develop their capability to assimilate the external knowledge obtained.

Figure 5

Specific construct for H2

Source: The authors

Table 4 shows the variables´ correlation included in the second hypothesis, which construct is presented in Figure 5. This model includes, in addition to human resources, financial resources as independent variables, as well as the assimilation capability, measured by “investment in science and technology innovation activities” (ICTI). This proxy was used, given that this investment is determined by the extent to which the firm invests in necessary mechanisms to interpret and process knowledge. From the correlation analysis it can be observed that all the independent variables have a positive relationship with the dependent variable (RCTI), and their correlation coefficients are significant at 5%, although their magnitude is low, these considerations will be taken into account when estimating the model in Table 5 (Gujarati & Porter, 2009).

Table 4

Pearson's correlation for H2

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

1. RCTI |

1 |

||||

2. No. MASTERS |

0.07* |

1 |

|||

3. No. TECHNOL |

0.16* |

0.53* |

1 |

||

4. ICTI |

0.16* |

0.18* |

0.37* |

1 |

|

5. TTEMPLEADOS |

0.17* |

0.48* |

0.76* |

0.42* |

1 |

Note: * Significant correlations at 5%

In order to contrast hypothesis 2, a probabilistic model of type Logit (Gujarati & Porter, 2009) was used (See Table 5). This model was used by the nature of the data, which adjusts better to a logistic distribution, also, since the dependent variable is dichotomous, what was established was to evaluate the probability of occurrence of an event due to the behavior of the independent variables (Gujarati & Porter, 2009). The dependent variable (RCTI) is dichotomous. It takes the value of 1 when the firm had at least one exchange with organizations from the National System of Science, Technology and Innovation (SNCTI), and 0 when the firm had no exchange with the SNCTI. The explanatory variables chosen are number of people with a master's degree (No. MASTERS), number of people with technologist degree (No. TECHNOL) and the science, technology and innovation investment activities (ICTI), the latter is transformed into a natural logarithm in order to homogenize the database and create robust estimations.

Table 5

Logistic regression results

RCTI |

Β |

S.E |

Z |

No. MASTERS |

0.04* |

0.02 |

2.11 |

No. TECHNOL |

0.01* |

0.00 |

2.10 |

ICTI |

0.07** |

0.03 |

2.56 |

TTEMPLEADOS |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.62 |

CONS |

-1.35*** |

0.32 |

-4.20 |

PROB > CHI2 |

0.00 |

|

|

PSEUDO R2 |

0.03 |

|

|

LOG LIKELIHOOD |

-979.75 |

|

|

AIC |

1969.50 |

|

|

BIC |

1996.05 |

|

|

N. |

1495 |

|

|

+p<.10 * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

This estimate allows us to show the probability of influence of human and financial resources on the assimilation of knowledge. According to the results obtained, the coefficients of the variables Number of Professionals with Master's Degrees and Number of Technologists are significant at 5%, therefore, as the number of workers with these levels of study increases, there is a greater probability of increasing the relations of the companies with the actors of the National System of Science, Technology and Innovation (RCTI) (Gujarati & Porter, 2009). Likewise, the coefficient of the variable investment in science, technology and innovation activities (ICTI) is significant at 1%, that is, if the company invests in this type of activity, the probability of assimilating more knowledge increases. With regard to the control variable (TTEMPLEADOS) it is not significant in the model, therefore, it can be inferred that it has no incidence on the TSI variable (Gujarati & Porter, 2009). Likewise, when estimating the marginal effects (See Table 6), the effects that the independent variables have on the dependent variable (RCTI) are corroborated.

Finally, when reviewing the AIC and BIC indicators (See Table 5) it can be established that the estimation was made with a correct specification of the model. In addition, the global significance test (PROB>CHI2) is highly significant, which allows rejecting the since the coefficients of the independent variables are equal to zero.

Table 6

Marginal effects

RCTI |

dy/dx |

S.E |

z-value |

No. MASTERS |

0.01* |

0.00 |

2.12 |

No. TECHNOL |

0.00* |

0.00 |

2.11 |

ICTI |

0.02** |

0.01 |

2.58 |

TTEMPLEADOS |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.62 |

+p<.10 * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Based on the assumption that the absorptive capability is a multidimensional construct, and that each dimension differs in its background, this study focuses on the tangible resources that influence the process of acquiring and assimilating knowledge. From the estimates made, it can be seen that there is a relationship between financial resources, human resources and the capacity to acquire and assimilate knowledge by companies; it is also shown that inter-organizational links have an effect on the potential absorption capacity of knowledge.

The findings allow for hypothesis 1 to be accepted, given that they indicate that a 1% increase in sales implies a 0.73% increase in the investment of new knowledge (p-value = 0.73). This suggests that greater financial resources translate into a greater knowledge assimilation capability of the environment’s knowledge (Alvarez-Melgarejo & Torres-Barreto, 2018b).

Additionally, the interaction of firms with other organizations has a direct impact on their ability to acquire external knowledge; this subject was previously validated through the literature (Yli-Renko, Autio, & Sapienza, 2001). The model evidences a positive influence on the knowledge acquisition capability (p-value=2.47) by being associated to Technological Development Centers, this suggests that this kind of Centers in Colombia have a positive effect due to their participation and role on research projects, their function in developing technology and supporting knowledge transfer activities.

In contrast, the interaction of firms with the national copyright agency (DNDA) negatively affects their knowledge acquisition capability (p-value = -4,04). This is due to the fact that the function of the DNDA concerning the design and execution of copyright policies creates ambiguity, given that it generates isolation mechanisms that protect the key resources and capabilities of firms (González & Nieto, 2007; Mahoney & Pandian, 1992; R. Reed & Defillippi, 1990), as well as impeding the transfer of technology (Lin, 2003), by generating barriers when it comes to accurately identify and using knowledge.

Regarding H2, firms with better qualified human resource are more likely to develop their knowledge assimilation capability on externally acquired knowledge. The marginal effects of the model predict that, by increasing the number of workers with a master's degree by one, the probability for firms to increase their absorptive capability (through relationships with SNCTI) will increase by 0.8%; and by increasing the number of workers with an associate’s degree by one, the probability increases by 0.1%. These results allow for hypothesis 2 to be accepted. It suggests that the intensity to which firms interact with different actors in their environment (in order to assimilate knowledge), is influenced by their worker’s level of qualification.

These findings are consistent with various academics who state that organizations with qualified staff are more receptive in assimilating external knowledge (Lund Vinding, 2006; Vega-Jurado, Gutiérrez-Gracia, & Fernández-De-Lucio, 2008). It should be noted that qualified employees are in constant interaction with different knowledge structures; a greater number of these structures means a better ability to assimilate knowledge (Máynez-Guaderrama, Cavazos-Arroyo, & Nuño-De la Parra, 2012).

On the other hand, the estimated Logit model supports a relationship between financial resources and the assimilation capability. The results suggest that for a 1% investment increase in science, technology or innovation, the probability for firms to interact with SNCTI increases by 2%. The aforementioned is coherent if one considers that interacting with other organizations implies investments in the exchange, processing and internalization of information. Therefore, the findings of this research validate the absorptive capability as an extensive process based on investment and accumulation of knowledge (Mowery, Oxley, & Silverman, 1996).

This study aims to fill the gap in the literature when inquiring about the background of the AC. Many of the preceding studies have used generalized measures, emphasizing organizational factors as support of the AC. Few studies assume a multidimensional construct and investigate the determinants for each dimension (Ebers & Maurer, 2014; Fosfuri & Tribó, 2008; Jansen, van den Bosch, & Volberda, 2005; Lane, Koka, & Pathak, 2006). This research is focused on the tangible determinants of the AC, by studying the effect of financial and human resources on the firm’s potential absorptive capability which is characterized by the ability to acquire and assimilate external knowledge.

The findings support the proposed hypotheses, and also validates the fact that AC components are influenced by different factors (Jansen et al., 2005; Todorova & Durisin, 2007). A causal relationship between a firm´s financial resources and their ability to acquire knowledge from the external environment is evidenced; the existence of a direct relationship between the firm’s ability to cooperate and interact with the external environment, and the generation of new knowledge acquisition capabilities are also evidenced in this study.

On the other hand, Colombian manufacturing firms that interact with Ministries and cooperate with Technological centers (6% and 3% respectively), have a greater potential in developing a knowledge acquisition capability. The reason behind this might be the interactions that generate an exchange of new knowledge.

On the other hand, firm’s capability to assimilate knowledge is positively influenced by human and financial resources. It highlights the role of qualified staff in the assimilation of external knowledge. This can be explained by the skills acquired through training processes. Likewise, the financial asset is decisive in developing activities that require an exchange of scientific and technological information. In this sense, our results support the proposition that tangible resources play an important role in the development of the PAC.

Finally, a remarkable result is related to financial resources. Although these have been scarcely considered in previous studies given their tangible characteristics; this research empirically demonstrates that they act as determinants in the development of the PAC in firms.

Considering the aforementioned findings, and also that resources are not available under the same conditions and proportions for all firms, and that the tangible determinants of each dimension are dissimilar, this study suggests that organizations may differ in their ability to manage PAC levels, and in their ability to achieve innovation and competitive advantages. This results are of interest for the business and management fields, since they prove that firms with greater acquisition and assimilation capabilities, may achieve greater administrative and technological characteristics than their competitors (Chen & Huang, 2009; Yli-Renko, Autio, & Sapienza, 2001), which in turn facilitates the development of competitive advantages.

Although the potential absorptive capability is a necessary condition in order to generate competitive advantages, it does not guarantee the exploitation of knowledge by itself. Therefore, in order for organizations to fully benefit from external knowledge, they need to develop absorptive capabilities. In this sense, it is proposed a future research work that delves into the determinants of the absorptive capability and the realized absorptive capability. This work acts as a basis to demonstrate the importance of analyzing the relationships between the determinants of these capabilities by using econometric and statistical techniques; additionally, it offers a path for further research on the subject.

Alder, J. (1965). Absorptive Capacity: The concept and its determinants (Bookings I). Washington.

Alvarez-Melgarejo, M., & Torres-Barreto, M. L. (2018a). Can resources act as capabilities foundations? A bibliometric analysis. Revista UIS Ingenierías, 17(2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.18273/revuin.v17n2-2018017

Alvarez-Melgarejo, M., & Torres-Barreto, M. L. (2018b). Recursos y capacidades: factores que mejoran la capacidad de absorción. I+ D Revista de Investigaciones, 12(2), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.33304/revinv.v12n2-2018005

Alvarez-Melgarejo, M., & Torres-Barreto, M. L. (2018c). Resources and Capabilities from Their Very Outset: a Bibliometric Comparison Between Scopus and the Web of Science. Review of European Studies, 10(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.5539/res.v10n4p1

Ambrosini, V., & Bowman, C. (2009). What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management?. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(1), 29–49.

Ambrosini, V., Bowman, C., & Collier, N. (2009). Dynamic capabilities: An exploration of how firms renew their resource base. British Journal of Management, 20(1), 9–24.

Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33–46.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Barney, J. B., & Arikan, A. M. (2001). The resource-based view: origins and implications. The Blackwell handbook of strategic management, 124-188.

Blázquez, M., & Mondino, A. (2012). Recursos organizacionales: Concepto, clasificación e indicadores. Instituto de Administración Facultad de Ciencias Económicas Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, 1, v11.

Bruni, D. S., & Verona, G. (2009). Dynamic marketing capabilities in Science‐based firms: An exploratory investigation of the pharmaceutical industry. British Journal of Management, 20(S1), 101–117.

Camisón, C., & Forés, B. (2010). Knowledge absorptive capacity: New insights for its conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Business Research, 63(7), 707–715.

Camisón, C., & Forés, B. (2014). Capacidad de Absorción: Antecedentes y resultados. Economia Industrial, 391, 13–22.

Chen, C., & Huang, J. (2009). Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance — The mediating role of knowledge management capacity. Journal of Business Research, 62(1), 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.11.016

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive Capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation.Adminstrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152.

Cruz, J., López, P., & Martín, G. (2009). La Influencia de las Capacidades Dinámicas sobre los Resultados Financieros de la Empresa. Cuadernos de Estudios Empresariales, 19(19), 105–128.

D’Adderio, L. (2011). Artifacts at the centre of routines: performing the material turn in routines theory. Journal of Institutional Economics, 7(2), 197–230.

DANE. (2015). Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. COLOMBIA - Encuesta de Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica - EDIT- Industria VII - 2013 – 2014. Retrieved from http://microdatos.dane.gov.co/index.php/catalog/532/get_microdata

DANE. (2017). Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. Metodología General Encuesta de Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica en la Industria Manufacturera – EDIT. Retrieved from https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/tecnologia-e-innovacion/encuesta-de-desarrollo-e-innovacion-tecnologica-edit

Danneels, E. (2002). The dynamics of product innovation and firm competences. Strategic Management Journal, 23, 1095–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.275

Dierickx, I., & Cool, K. (1989). Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage. Management Science, 35(12), 1504–1511.

Dyer, J. H., & Singh, H. (1998). The relational vew: coopertive strategy and sources of interogranizational competitive advantage. The Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660–679. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1998.1255632

Ebers, M., & Maurer, I. (2014). Connections count: How relational embeddedness and relational empowerment foster absorptive capacity. Research Policy, 43(2), 318–332.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: what are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21, 1105–1121.

Escandón, D. M., Rodriguez, A., & Hernández, M. (2013). La importancia de las capacidades dinámicas en las empresas born global colombianas. Cuadernos de Administracion, 26(47), 141–163.

Flatten, T. C., Engelen, A., Zahra, S. A., & Brettel, M. (2011). A measure of absorptive capacity: Scale development and validation. European Management Journal, 29(2), 98–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2010.11.002

Forés, B., & Camison, C. (2008). La capacidad de absorción de conocimiento: factores determinantes internos y externos. Dirección y Organización, (36), 35–50.

Fosfuri, A., & Tribó, J. A. (2008). Exploring the antecedents of potential absorptive capacity and its impact on innovation performance. Omega, 36(2), 173–187.

Galbreath, J. (2005). Which resources matter the most to firm success? An exploratory study of resource-based theory. Technovation, 25, 979–987.

García-Morales, V. J., Ruiz-Moreno, A., & Llorens-Montes, F. J. (2007). Effects of technology absorptive capacity and technology proactivity on organizational learning, innovation and performance: An empirical examination. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 19(4), 527–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320701403540

Garzón-castrillón, M. A. (2016). Capacidad dinámica de absorción. Estudio de caso. Orinoquia, 20(1), 97–118.

González Campo, C. H., & Hurtado Ayala, A. (2014). Propuesta de un indicador de capacidad de absorción del conocimiento (ICAC-COL): evidencia empírica para el sector servicios en Colombia. Revista Facultad de Ciencias Económicas: Investigación y Reflexión, 22(2), 29–46.

González, N., & Nieto, M. (2007). El papel de la ambigüedad causal como variable mediadora entre las prácticas de recursos humanos de alto compromiso y los resultados corporativos. Revista Europea de Direccion y Economia de La Empresa, 16(4), 107–126.

Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2009). Econometría. (McGraw-Hill, Ed.) (Quinta Edi).

Helfat, C. E. (1997). Know-how and asset complementarity and dynamic capability accumulation: The case of R&D. Strategic Management Journal, 18(5), 339–360.

Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2003). The dynamic resource‐based view: Capability lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 997–1010.

Herzog, L. T. (2001). Aproximación a la ventaja competitiva con base en los recursos. Boletín de Estudios Económicos, 56(172), 5–21.

Ismail, A. I., Rose, R. C., Uli, J., & Abdullah, H. (2012). The relationship between organisational resources, capabilities, systems and competitive advantage. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 17(1), 151–173.

Jansen, J. J., van den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2005). Managing potential and realised absorptive capacity: How do organisational antecedents matter?. Academy of Management Journal, 48(6), 999–1015. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2005.19573106

Kale, P., & Singh, H. (2007). Building firm capabilities through learning: The role of the alliance learning process in alliance capability and firm-level alliance success. Strategic Management Journal, 20(10), 981—1000. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj

Lane, P. J., Koka, B. R., & Pathak, S. (2006). The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 833–863. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.22527456

Lane, P. J., & Lubatkin, M. (1998). Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning. Strategic Management Journal, 19, 461–477. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199805)19:5<461::AID-SMJ953>3.3.CO;2-C

Lane, P. J., Salk, J. E., & Lyles, M. A. (2001). Absorptive capacity, learning, and performance in international joint ventures. Strategic Management Journal, 22(12), 1139–1161.

Leal-Rodríguez, A. L., Roldán, J. L., Leal-Millán, A., & Ariza-Montes, J. (2014). From potential absorptive capacity to innovations outcomes in project teams : The moderating effects of relational learning and. International Journal of Project Management, 32(6), 894–907. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.01.005

Liao, J., Welsch, H., & Stoica, M. (2003). Organizational absorptive capacity and responsiveness: An empirical investigation of Growth-Oriented SMEs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(1), 63–85.

Lin, B. W. (2003). Technology transfer as technological learning: a source of competitive advantage for firms with limited R&D resources. R&D Management, 33(3), 327–341.

López, M. D., Mejía, J. C., & Schmal, R. (2006). Un acercamiento al concepto de la transferencia de tecnología en las universidades y sus diferentes manifestaciones. Panorama Socioeconómico, 24(32), 70–81.

Lund Vinding, A. (2006). Absorptive capacity and innovative performance: A human capital approach. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 15(4–5), 507–517.

Mahoney, J. T., & Pandian, J. R. (1992). The Resource -Based View Within the Conversation of Strategic Management. Strategic Management Journal, 13(5), 363–380.

Masteika, I. (2015). Dynamic Capabilities in Supply Chain Management. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 213, 830–835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.485

Máynez-Guaderrama, A. I., Cavazos-Arroyo, J., & Nuño-De la Parra, J. P. (2012). La influencia de la cultura organizacional y la capacidad de absorción sobre la transferencia de conocimiento tácito intra-organizacional. Estudios Gerenciales, 28, 191–211.

McKelvie, A., & Davidsson, P. (2009). From resource base to dynamic capabilities: an investigation of new firms. British Journal of Management, 20(1).

Minbaeva, D., Pedersen, T., Björkman, I., Fey, C. F., & Park, H. J. (2003). MNC knowledge transfer, subsidiary absorptive capacity and HRM. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(6), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2013.43

Miranda, J. (2015). El modelo de las capacidades dinámicas en las organizaciones. Investigacion Adminstrativa, 44(116), 81–93.

Montero Granados. R (2016): Modelos de regression lineal multiple. Documentos de Trabajo en Economía Aplicada. Universidad de Granada. España. Retrieved from https://www.ugr.es/~montero/matematicas/regresion_lineal.pdf

Mowery, D. C., & Oxley, J. E. (1995). Inward technology transfer and competitiveness: the role of national innovation systems. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 19(1), 67–93.

Mowery, D. C., Oxley, J. E., & Silverman, B. S. (1996). Strategic alliances and interfirm knowledge transfer. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 77–91.

Mukaka, M. M. (2012). A guide to appropriate use of Correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Medical Journal, 24(3), 69–71.

Murovec, N., & Prodan, I. (2009). Absorptive capacity, its determinants, and influence on innovation output: Cross-cultural validation of the structural model. Technovation, 29(12), 859–872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2009.05.010

Nieto, M., & Quevedo, P. (2005). Absorptive capacity, technological opportunity, knowledge spillovers, and innovative effort. Technovation, 25(10), 1141–1157.

Nieves, J., & Haller, S. (2013). Building dynamic capabilities through knowledge resources. Tourism Management, 40(2014), 224–232.

Olea-Miranda, J., Contreras, O., & Barcelo, M. (2016). Las capacidades de absorción del conocimiento como ventajas competitivas para la inserción de pymes en cadenas globales de valor. Estudios gerenciales, 32(139), 127-136.

Peris, M. L., Mestre, M. J., & Palao, C. G. (2011). La relación entre la capacidad de absorción del conocimiento externo y la estrategia empresarial: un análisis exploratorio. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 20(1), 69–87.

Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14(3), 179–191.

Rangone, A. (1999). A resource-based approach to strategy analysis in small-medium sized enterprises. Small Business Economics, 12(3), 233–248.

Reed, R., & Defillippi, R. J. (1990). Causal ambiguity, barriers to imitation, and sustainable competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 15(1), 88–102.

Sáez de Viteri Arranz, D. (2000). El potencial competitivo de la empresa: Recursos, capacidades, rutinas y procesos de valor añadido. Investigaciones Europeas de Dirección y Economía de La Empresa, 6(3), 71–86.

Schriber, S., & Löwstedt, J. (2015). Tangible resources and the development of organizational capabilities. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 31, 54–68.

Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350.

Teece, D. J., & Pisano, G. (1994). The Dynamic Capabilities of Firms: An Introduction", Industrial & Corporate Change. Industrial and Corporate Change, 3(3), 537–556.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management. StraStrategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533.

Todorova, G., & Durisin, B. (2007). Absorptive Capacty: Valuing a Reconceptualization. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 774–786.

Torres-Barreto, M. L. (2017). Innovaciones de productos y financiación pública de I+ D: Cómo manejar la heterocedasticidad y la autocorrelación. I+ D Revista de Investigaciones, 9(1), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.33304/revinv.v09n1-2017013

Torres-Barreto, M. L., & Antolinez, D. (2017). Exploring the boosting potential of intellectual resources and capabilities on firm´s competitiveness. Revista Espacios, 38(31), 35.

Tu, Q., Vonderembse, M. A., Ragu-Nathan, T. S., & Sharkey, T. W. (2006). Absorptive capacity: Enhancing the assimilation of time-based manufacturing practices. Journal of Operations Management, 24(5), 692–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2005.05.004

Van den Bosch, F. A., Volberda, H. W., & De Boer, M. (1999). Coevolution of firm absorptive capacity and knowledge environment: Organizational forms and combinative capabilities. Organization Science, 10(5), 551–568.

Van den Bosch, F., Van Wijk, R., & Volberda, H. W. (2003). Absorptive capacity: Antecedents, models and outcomes. ERIM Report Series Reference No. ERS-2003-035-STR. Retrieved from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=411675

Vega-Jurado, J., Gutiérrez-Gracia, A., & Fernández-De-Lucio, I. (2008). Analyzing the determinants of firm’s absorptive capacity: Beyond R&D. R&D Management, 38(4), 392–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2008.00525.x

Wang, C. L., & Ahmed, P. K. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. International Journal Management Reviews, 9(1), 31–51.

Yli-Renko, H., Autio, E., & Sapienza, H. J. (2001). Social capital, knowledge acquisition, and knowledge exploitation in young technology-based firms. Strategic Management Journal, 22(6–7), 587–613. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.183

Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). Absorptive capacity: A review, reconceptualization, and extension. Academy of Management Review, 27(2), 185–203.

Zahra, S. A., Sapienza, H. J., & Davidsson, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship and Dynamic Capbilities: A Review, Model and Research Agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 917–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00616.x

Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate Learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organization Science, 13(3), 339–351.

1. PhD. In Economics. Chief Of Staff - Finance & Management Research Group, chair of GALEA Laboratory. Universidad Industrial de Santander, Colombia. mltorres@uis.edu.co

2. MBA (c). Porter Research Group. Universidad de Investigación y Desarrollo. Colombia. mileidyalvarez@hotmail.es

3. MSc. In Economics. Master Researcher. AGROSAVIA - Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria, Colombia. fmontealegre@agrosavia.co

[Index]

revistaespacios.com

This work is under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 International License