Vol. 41 (Issue 14) Year 2020. Page 3

UPANUN, Kawee S. 1; SORNSARUHT, Puris 2

Received: 14/07/2019 • Approved: 04/04/2020 • Published 23/04/2020

ABSTRACT: Thailand has become the 10th most popular tourist destination in the world, which is expected to greet 41 million foreign guests in 2019. Given this significance, the authors undertook a study using a structural equation model [SEM] and LISREL 9.1 to assess the opinions of 542 guests on how a Thai five-star hotel’s reputation (RP) was affected by service quality (SQ), guest trust (TR), and guest satisfaction (ST). Results determined that the factors most important were SQ, TR, and ST, respectively. |

RESUMEN: Tailandia se ha convertido en el décimo destino turístico más popular del mundo y se espera que reciba a 41 millones de huéspedes extranjeros en 2019. Dada esta importancia, los autores realizaron un estudio utilizando un modelo de ecuación estructural [SEM] y LISREL 9.1 para evaluar las opiniones de los 542 invitados explicaron cómo la reputación de un hotel tailandés de cinco estrellas (RP) se vio afectada por la calidad del servicio (SQ), la confianza del huésped (TR) y la satisfacción del huésped (ST). Los resultados determinaron que los factores más importantes fueron SQ, TR y ST, respectivamente. |

Thailand today is the tenth most popular destination in the world, with foreign tourist visitors expected to reach 41 million in 2019 (Marukatat, 2018). Foreign travelers also spend more money in the Kingdom than anywhere else in Asia, which has made Thailand the fourth-most-profitable tourism destination globally (Ekstein, 2018). Also, according to the World Travel & Tourism Council (2017), travel and tourism contributed $82.5 billion to Thailand’s gross domestic product [GDP] in 2016, representing 20.6% of Thailand’s total GDP. Additionally, the tourism sector supports over 15% of Thailand’s total employment, which represents over 5.7 million jobs.

Given the significance of these numbers and the impact on Thailand, its economy, and business development, the authors opted to undertake a study on what factors affect a five-star hotel's reputation. However, first, we need to understand just what a ‘five-star' hotel is.

A hotel rating system embraces two parts, which includes a basic registration standard as well as a grading standard (Callan, 1993). The basic registration standard is the minimum quality and physical requirement that a hotel property must meet, with the evaluation criteria an extension of basic requirements of qualitative and intangible services, allowing a hotel comparison to other properties.

There is also a common misconception around the world that there is an international standard for a hotel with 'five-stars,' but in reality, there is not (Amey, 2015), with hotel star ranking systems differing widely from country to country. However, there is some consensus as to what makes a hotel a 'five-star' hotel, with the numbers of 'stars' related to the hotel's level of service, amenities, cleanliness, location, room sizes, and price. The ‘star’ ranking system began with the Forbes Travel Guide in the U.S. in the 1950s, but in the U.K., tourist authorities such as VisitBritain and VisitScotland are in charge today (LaRock, 2018).

Additional research complications arise from the fact that between 1994 and 2014, there were 70 qualified scholarly research articles which used a variety of terms used to discuss the high-end hotel industry (Chu, 2014). These terms included ‘luxury hotels,' ‘deluxe hotels,' ‘upscale hotels,' ‘high-end hotels,' ‘palace hotels' (France), and ‘four- or five-star hotels.' Furthermore, one can find in hotel guides and academic papers the terms ‘upscale’ in China (Hsu, Oh & Assaf, 2011), ‘first class’ in Scandinavia (Mattsson, 1994), ‘moderate deluxe,' ‘deluxe,' and ‘superior deluxe’ (Sanyal, 2008).

However, from a search of the Crossref database using the phrase “five-star hotel”, 225,423 entries were returned. A search of Google using the same search phrase returned 12.7 million results. Therefore, from this analysis, the authors selected the phrase 'five-star hotel' to describe a property wherein the services and standards are at the highest level available within Thailand.

The phrase ‘five-star’ hotel was also adopted in 2004 for the launch of the Thailand Hotel Standard program (Narangajavana & Hu, 2008; Thailand Standards Hotel Directory, 2017). This program and its assessment committee began with representatives from the Thai Hotels Association [THA], the Tourism Authority of Thailand [TAT], the Association of Thai Travel Agents, and university hotel management programs. Individuals from these groups were called upon to conduct a voluntary annual assessment, and certification inspections (Narangajavana & Hu, 2008), with each hotel inspected and scored based on one to five stars.

Criteria used in the ranking process included the hotel's construction and facilities, maintenance, and service. Furthermore, starting in 2011, inspections started to be undertaken by no less than four individuals representing a minimum of three organizations, whose standard's criteria was approved by the Thailand Hotel Standard Task Force (Thailand Standards Hotel Directory, 2017).

As a comparison, in the United Kingdom, five-star hotels must also offer fitness and spa facilities, valet parking, butler and concierge services, 24-hour reception and room service, and a full afternoon tea. In France, however, the standards are regulated by the French Government (Amey, 2015). In 2012, the French government overhauled their ranking system, and today a five-star hotel must have guest rooms of at least 24 square meters, which are provided with air conditioning, valet parking, room service, a concierge, and an escort to the room at the time of check-in (Chavanne, 2019). The staff must also be able to speak two foreign languages, including English.

Support for the importance of a five-star hotel’s staff was revealed in a Bangkok study in which the authors stated that employees play an essential role in making a hotel's brand 'come alive' (Kimpakorn & Tocquer, 2009). Gotsi and Wilson (2001) also determined that the staff’s role is pivotal in the corporate reputation management process, which is affected by the actions of every business unit, department, and staff member.

Thailand has also become the tenth most popular tourist destination in the world, with 60% of bookings made by Chinese and 55% of bookings made by Indians were in four-star and five-star hotels (“US remains top source," 2019). International travelers from the United Arab Emirates, Israel, and South Africa have also emerged as high-value markets for hotels, as 70% of total bookings made by these nationalities were in four-star and five-star hotels. These statistics support the Thai government's focus on attracting more high-end arrivals.

Furthermore, in 2019 Thailand is projecting 41.1 million foreign tourists. Thailand, therefore, has become a very attractive global tourism brand, and as a consequence, has been transformed into a major world tourist destination (Marukatat, 2018), which is now projecting 65 million visitors within a decade (Chuwiruch, 2019).

Therefore, the study aims to investigate the importance and interrelationships of guest satisfaction (ST), the hotel’s service quality (SQ), and a guest’s trust (TR) on a five-star hotel’s reputation (RP). Additionally, the paper aims to contribute to the literature and a Thai hotel’s reputation by identifying which factors play the most significant role. It reports on a survey of both Thai and foreign guests distributed across six regions within the Kingdom.

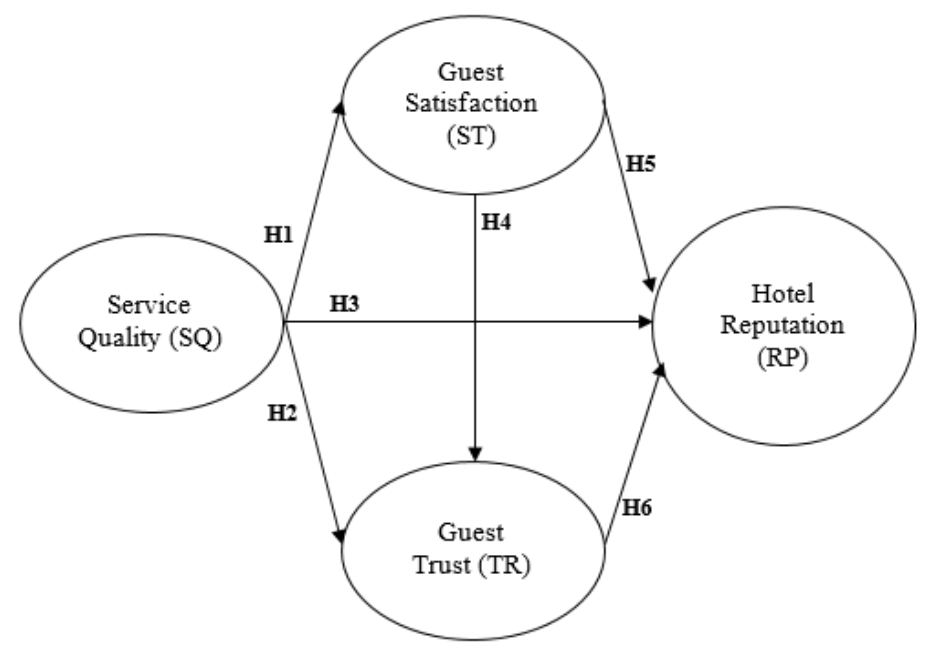

Furthermore, the paper is divided into four main sections. Additionally, underlying theory was investigated to obtain the variables and the creation of the hypotheses and a conceptual model in Figure 1. The methodology is detailed in section two, which includes the population and sample, the research tools, data collection, and data analysis. Section three details the results, which is followed by the conclusion and discussion in section four.

1. The authors wished to develop a structural equation model [SEM] of factors to analyze how guests perceive a five-star hotel’s reputation.

2. To compare the interrelationships of these factors and determine their importance to hoteliers and their guests.

After a review of the literature and theory, the authors determined that the hotel’s reputation (RP) was affected by guest satisfaction (ST), the hotel’s service quality (SQ), and a guest’s trust (TR). From this, six hypotheses and a conceptualized framework were developed (Figure 1):

H1: SQ directly influences ST.

H2: SQ directly influences TR.

H3: SQ directly influences RP.

H4: ST directly influences TR.

H5: ST directly influences RP.

H6: TR directly influences RP.

Figure 1

Conceptualized model

A quantitative method was adopted for the primary data collection stage of the study, which involved a questionnaire survey technique to test the theoretical model of factors influencing a Thai five-star hotel’s reputation.

Thai and foreign guests staying in one of 10 five-star hotels spread throughout six regions in Thailand was the population for the study. From the evaluation statistical sample size theory, it was determined that a common method for determining a sample’s size was to use a multiple times the number of observed variables, with the multiple ranging from 10-20 (Schumacker & Lomax, 2010). Therefore, after allocating for sampling and questionnaire non-response errors, a target of 600 Thai and foreign guests was initially set (Table 1), whose sample was selected by use of systematic random sampling. The survey commenced in November 2017 and was completed in late February 2018.

Table 1

Target sample

sizes by region

Regions

|

Sample |

||

Thai |

Foreign |

Total |

|

North East (Isan) |

50 |

50 |

100 |

Northern |

50 |

50 |

100 |

Central |

50 |

50 |

100 |

Eastern |

50 |

50 |

100 |

Southern |

50 |

50 |

100 |

Bangkok |

50 |

50 |

100 |

Totals |

300 |

300 |

600 |

From the focus group session conducted in the university library, five academic, hotel, and tourism industry experts shared their views on what constitutes a hotel’s reputation (RP), as well as factors involved in guest satisfaction (ST), the hotel’s service quality (SQ), and what factors relate to a guest’s trust (TR). Furthermore, from the most current version of the Thailand Standard Hotels database, hotels in each of Thailand’s six regions were investigated and suggested (Table 2).

Table 2

Five-star hotels and

their survey location

Hotel/Resort |

Location |

Anantara Chiang Mai Resort |

Chiang Mai |

Centara Grand at Central Plaza Ladprao |

Bangkok |

Conrad Bangkok |

Bangkok |

Dusit Thani Hua Hin |

Hua Hin |

JW Marriott Phuket Resort & Spa |

Phuket |

Paradee Resort Ko Samet |

Rayong |

Pullman Khon Kaen Raja Orchid Hotel |

Khon Kaen |

Royal Muang Samui Villas |

Koh Samui |

Sheraton Hua Hin Resort & Spa |

Hua Hin |

The Sukhothai Bangkok |

Bangkok |

Source: Thailand Standards Hotel Directory (2017).

The tools used to collect data in this research consisted of a structured interview as well as the analysis and synthesis of research from the theoretical and conceptual framework.

Preliminary item reliability testing was obtained by using Cronbach’s α and ranged from 0.96 – 0.98, which was ranked as ‘excellent’. This included part 2’s SQ with five items (α = 0.98), part three’s ST with four items (α = 0.97), part four's TR with four items (α = 0.96), and part five's four items concerning the hotel's reputation (RP) (α = 0.96). Each parts' observed variables, their confirmatory factor analysis [CFA] results and the Cronbach's α reliability test results are also found in Tables 3 and 4.

The research findings are as follows.

Results from part 1 of the hotel guest questionnaire determined that 59.78% were men. Hotel guest age was nearly evenly distributed across three groups, with 21-30, 31-40, and 41-50, is 21.03%, 31.37%, and 29.70%, respectively. Also, single guests represented 34.32%, while those that were married represented 33.39%. Finally, a significant number (15.87%), viewed their relationship status as ‘other’, suggesting that high-end hotels need to pay close attention to non-traditional travelers and guests.

Table 3

Hotel guests characteristics

(n=542)

Gender |

Frequencies |

% |

Male |

324 |

59.78 |

Female |

218 |

40.22 |

Total |

542 |

100 |

Age |

|

|

21-30 years of age. |

114 |

21.03 |

31-40 years of age. |

170 |

31.37 |

41-50 years of age. |

161 |

29.70 |

51-60 years of age. |

87 |

16.05 |

Over 60 years of age. |

10 |

1.85 |

Total |

542 |

100 |

Education level |

|

|

Primary school |

17 |

3.14 |

Lower secondary school |

97 |

17.90 |

High school |

96 |

17.71 |

Vocational Certificate / Diploma |

130 |

23.99 |

Bachelor's Degree or higher |

202 |

37.27 |

Total |

542 |

100 |

Relationship status |

|

|

Single |

186 |

34.32 |

Married |

181 |

33.39 |

Divorced/widowed |

89 |

16.42 |

Other |

86 |

15.87 |

Total |

542 |

100 |

The LISREL 9.10 software program was used to conduct the study’s CFA analysis and subsequent SEM. All statistics are absolute fit measures and indicate the fit between the model and the data. If the chi-square (χ2) statistic is non-significant (p ≥ 0.05), the model fits the data (Voerman, 2003). Suggested approximate fit indexes also include the goodness of fit index [GFI], adjusted goodness of fit index [AGFI], normed fit index [NFI], and the comparative fit index [CFI], with each having values ≥ 0.90 to indicate a good model fit (Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, 2008; Satorra & Bentler, 2001; Schumacker & Lomax, 2010). Furthermore, authors have suggested the use of both the RMSEA and GFI as two other absolute fit indices (Voerman, 2003), with RMSEA values ≤0.05 indicating a good fit (Byrne, 1998). The GFI statistic, however, indicates a better fit the higher it becomes, with a cut-off point of .90 being suggested (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The comparative fit index [CFI] statistic is also suggested as an incremental fit measure (Bentler & Bonett, 1980). Also, the root mean square residual [RMR] should have a value of ≤ 0.05, which suggests an acceptable model (Byrne, 1998). Significance of standardized regression weight (standardized loading factor) estimates signifies that the indicator variables are significant and representative of their latent variable. Results showed that χ2 = 0.82 which was non-significant. Therefore, from the GoF analysis, χ2/df = 0.83, RMSEA = 0.0000, GFI = 0.98, AGFI = 0.97, RMR = 0.01, SRMR = 0.01, NFI = 0.99, and CFI = 1.00 all passed. Finally, the values for α = 0.96-0.98, which were considered excellent.

Some scholars have suggested the use of a two-step analysis on both the internal and external variables when a measurement model’s analysis (Anderson & Gerbing, 1998). Therefore, from the use of LISREL 9.10, both a CFA (Table 4 and Table 5) and SEM was conducted (Jöreskog, Olsson, & Fan, 2016).

Table 4

CFA results for SQ

Latent variable |

a |

AVE |

CR |

Observed variables |

loading |

R2 |

Service quality (SQ) |

0.98 |

0.90 |

0.98 |

Tangibles (SQ1) |

0.96 |

.93 |

Reliability (SQ2) |

0.99 |

.97 |

||||

Responsiveness (SQ3) |

0.96 |

.93 |

||||

Assurance (SQ4) |

0.90 |

.81 |

||||

Empathy (SQ5) |

0.94 |

.89 |

Note: Chi-Square = 0.00, df = 2, p-value = 0.99764, RMSEA = 0.000,

AVE = average variance extracted, CR (t-value) = critical ratio

-----

Table 5

CfA results for

ST, TR, and RP

Latent variables |

a |

AVE |

CR |

Observed variables |

loading |

R2 |

Guest Satisfaction (ST) |

0.97 |

0.87 |

0.96 |

Pleased with accommodations and facilities (ST1) |

0.85 |

.73 |

|

|

|

Excellent service (ST2) |

0.97 |

.94 |

|

|

|

|

Happy about hotel choice (ST3) |

0.94 |

.89 |

|

|

|

|

Service staff (ST4) |

0.97 |

.95 |

|

Guest Trust (TR) |

0.96 |

0.88 |

0.95 |

Hotel reliability (TR1) |

0.89 |

.79 |

|

|

|

Good service quality (TR2) |

0.96 |

.92 |

|

|

|

|

Honoring commitments (TR3) |

0.96 |

.92 |

|

Hotel Reputation (RP) |

0.96 |

0.84 |

0.96 |

Good reputation (RP1) |

0.93 |

.87 |

|

|

|

Corporate social responsibility (RP2) |

0.91 |

.84 |

|

|

|

|

Trustworthy (RP3) |

0.92 |

.85 |

|

|

|

|

Appealing facilities (RP4) |

0.92 |

.84 |

Note: Chi-Square = 17.09, df = 24, p-value = 0.84477, RMSEA = 0.000,

AVE = average variance extracted, CR (t-value) = critical ratio

Table 6 shows the values from the r testing (Ratner, 2009), as well as the results from the direct effects [DE], indirect effects [IE], and the total effects [TE] analysis (Ladhari, 2009). The r can also have a value from −1 to +1. The larger the absolute value of the coefficient, the stronger the relationship between the variables. Ranked in importance, factors influencing RP were SQ, TR, and ST, with total effect [TE] values of 0.89, 0.71, and 0.60, respectively.

Table 6

Correlation coefficient r results

Dependent variables |

R2 |

Effects |

Independent variables |

||

SQ |

ST |

TR |

|||

Guest Satisfaction (ST) |

.87 |

DE |

0.93** |

|

|

IE |

- |

|

|

||

TE |

0.93** |

|

|

||

Guest Trust (TR) |

.81 |

DE |

0.19** |

0.76** |

|

IE |

0.71** |

- |

|

||

TE |

0.90** |

0.76** |

|

||

Hotel Reputation (RP) |

.79 |

DE |

0.19** |

0.07 |

0.71** |

IE |

0.70** |

0.53** |

- |

||

TE |

0.89** |

0.60** |

0.71** |

||

Note: *Sig. ≤ .05, **Sig. ≤ .01, R2 = coefficient of determination

All the causal variables in the SEM had a positive effect on a five-star hotel's reputation (RP), which can be combined to explain the shared variance of the factors affecting RP (R2) by 79% (Table 7). Furthermore, Table 6 further supports the reliability of the SEM’s results as all factors showed excellent levels of internal consistency, as their composite reliability [CR] is between 0.95 and 0.98.

Table 7

Standard coefficients of influences in

the SEM of variables that influence RP

Latent Variables |

MC |

BV |

BQ |

ST |

Service quality (SQ) |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Guest Satisfaction (ST) |

.91** |

1.00 |

|

|

Guest Trust (TR) |

.85** |

.91** |

1.00 |

|

Hotel Reputation (RP) |

.85** |

.89** |

.90** |

1.00 |

rV (AVE) |

0.89 |

0.89 |

0.88 |

0.84 |

rC (Composite Reliability) |

0.98 |

0.97 |

0.95 |

0.96 |

√AVE |

0.94 |

0.94 |

0.94 |

0.92 |

Note: **Sig. ≤ .01

Table 8 shows the results of hypotheses testing.

Table 8

Final hypotheses

testing results

Hypotheses |

Coef. |

t-value |

Results |

H1: SQ directly influences ST |

0.93 |

24.60** |

consistent |

H2: SQ directly influences TR |

0.19 |

3.06** |

consistent |

H3: SQ directly influences RP |

0.19 |

3.28** |

consistent |

H4: ST directly influences TR |

0.76 |

11.07** |

consistent |

H5: ST directly influences RP |

0.07 |

0.88 |

inconsistent |

H6: TR directly influences RP |

0.71 |

10.64** |

consistent |

Note: *Sig. < .05, **Sig. < .01

-----

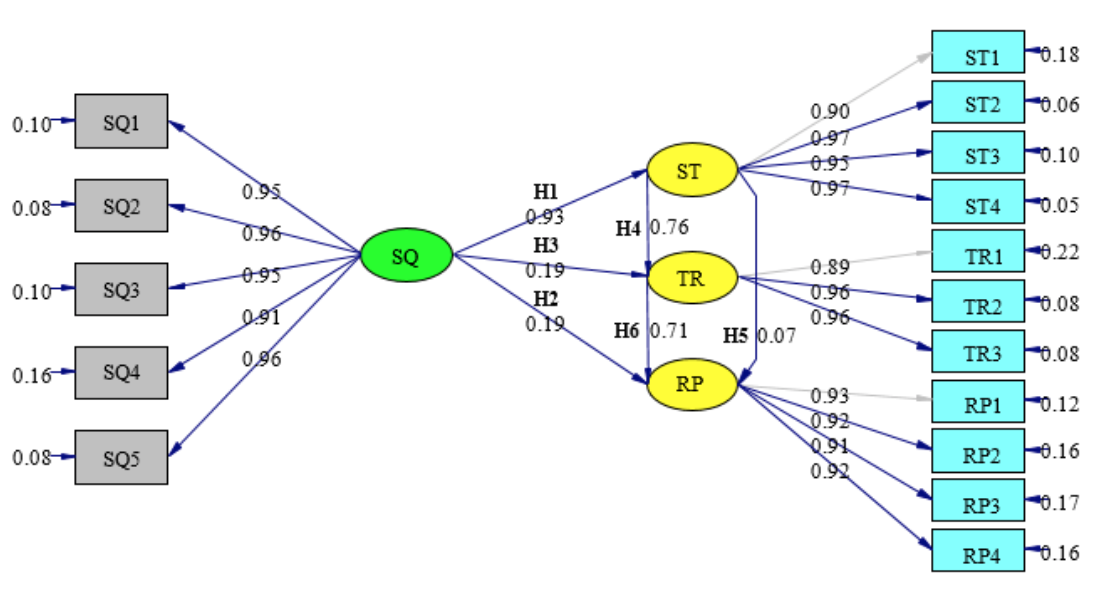

Figure 2

Final model

Note: Chi-Square = 49.92, df = 60, p-value = 0.81996, RMSEA = 0.000

The results from the SEM analysis showed that H1 had a strong and positive relationship between SQ and ST, as r = 0.93, t-value = 24.60, and p≤0.01 (Table 8). However, H2’s relationship between SQ and TR was weak but positive as r = 0.19, t-value = 3.05, and p≤0.01. Finally, the relationship between SQ and RP examined in H3 was shown to also be direct and positive as r = 0.19, t-value = 3.28, and p≤0.01.

Numerous studies have verified the importance of these relationships. In Southeast Asia, international guests view personal care, friendliness, and personal warmth and acknowledgment as important elements in SQ (Ariffin & Maghzi, 2012). In Israel, hotels were reported to use ratings as a pricing tool, with the star ranking system being a significant predictor of a hotel's decision in setting prices (Israeli & Uriely, 2000; Lollar, 1990). Therefore, changes in hotel performance are associated with service quality improvement as a result of participating in the hotel rating system (Lollar, 1990). Additionally, competitive marketing demands local and international hotels to seek standards and tools to reflect their SQ (Narangajavana & Hu, 2008).

Furthermore, H4 also established a strong and positive relationship between ST and TR, as r = 0.76, t-value = 11.07, and p≤0.01. However, H5’s relationship between ST and RP was determined to be unsupported.

Other research has also confirmed the value of ST within the hotel industry (Karunaratne & Jayawardena, 2011), with ST a crucial concept for a hotel to understand if it wants to remain competitive and grow. The delivery of high-quality service is, therefore, a crucial element in maintaining a sustainable competitive advantage (Angelova & Zekiri, 2011).

As the foundation for any successful business is ST, which leads to repeat purchase, positive word of mouth, and eventually, brand loyalty (Seeman & O'Hara, 2006). However, hoteliers should be aware that ST does not equal hotel loyalty (Shoemaker & Lewis, 1999). This is in agreement with Skogland and Siguaw (2004), which also determined that in big-city hotels, ST did always equal repeat business (hotel loyalty), as business travelers are the least loyal.

In Thailand, it has been suggested that hotel entrepreneurs should use staff development programs and modern technologies to maximize ST (Mingkhwansakul & Rungsawanpho, 2018). This is consistent from the findings concerning the Italian hotel industry in which it was suggested that innovation and the implementation of new technologies and supplementary services represent the driver for the creation of value and international competitiveness (Capocchi, 2014).

Finally, the relationship between TR and RP examined in H6 was shown to also be strong and positive as r = 0.71, t-value = 10.64, and p≤0.01. Support for this relationship strength can be found in the SERVQUAL Model's ‘assurance', which is discussed in terms of employee knowledge and courtesy and the worker's ability to inspire trust and confidence (Narangajavana & Hu, 2008). It has also been stated that customer TR has a direct influence on customer loyalty and an organization’s effectiveness (Skogland & Siguaw, 2004). Word-of-mouth also plays a significant role in TR (Zeba & Ganguli, 2016), with TR playing a significant role in determining commitment between consumers and organizations (Morgan & Hunt, 1994).

A five-star hotel’s reputation (RP) was originally conceptualized to be influenced by its good reputation (RP1), its participation in community corporate social responsibility [CSR] (RP2), the trust placed in by the guest (RP3), and finally, how appealing the facilities were to each of the guest (RP4). The results showed that all four factors were nearly equally matched in their importance by the survey participants (0.91-0.93).

Specifically, CSR over the years has become an influential factor in RP, with CSR shown to have positively influenced Tehran four and five-star hotels' financial and non-financial performance (Ghaderi, et al., 2019). It appears, therefore, that a hotel’s performance, profits, and value are enhanced by CSR engagement activities (Orlitzky, et al., , 2003).

Also, effective and efficient hotel operations that surpass guests' expectations make a hotel's reputation exceptional, which increases the hotelier’s profitability (Singh, et al., 2017). Other research has suggested that a guest’s expectations of hotel hospitality are influenced by personal factors such as gender, the purpose of stay, and nationality (Ariffin & Maghzi, 2012). Finally, hotels are not regulated or certified by any central global authority (Cser & Ohuchi, 2008), so ‘five-star' on one continent might be considerably different from ‘five-star' on another continent.

Amey, A. (2015, March 24). Afternoon tea, valet parking and 24-hour room service: What really makes a five-star hotel? Mail Online. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y54eohre

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1998). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(5), 204–215.

https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.103.3.411

Angelova, B., & Zekiri, J. (2011). Measuring customer satisfaction with service quality using American Customer Satisfaction Model (ACSI Model). International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 1(3), 232-258. Retrieved from http://hrmars.com/admin/pics/381.pdf

Ariffin, A. A. M., & Maghzi, A. (2012). A preliminary study on customer expectations of hotel hospitality: Influences of personal and hotel factors. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(1), 191 – 198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.04.012

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness-of-fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588-600. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.88.3.588

Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Callan, R. J. (1993). An appraisal of UK hotel quality grading schemes. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 5(5), 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596119310046907

Capocchi, A. (2014). An overview of the Italian hotel industry today. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 15(4), 425 – 446. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008x.2014.921781

Chavanne, P. (2019). The official hotel star system in France explained. Tripsavvy. Retrieved form https://tinyurl.com/y242xh8o

Chu, Y. (2014). A review of studies on luxury hotels over the past two decades. Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13913. Iowa State University. Retrieved from https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13913/

Chuwiruch, N. (2019, June 20). Thailand's $13 billion plan could woo 65 million tourists yearly. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y58nusrw

Cser, K., & Ohuchi, A. (2008). World practices of hotel classification systems. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 13(4), 379-398. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660802420960

Ekstein, N. (2018, October 10). Travelers spend more money in Thailand than anywhere else in Asia: It’s the fourth-most-profitable tourism destination in the world. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y59eere6

Ghaderi, Z., Mirzapour, M., Henderson, J. C., & Richardson, S. (2019). Corporate social responsibility and hotel performance: A view from Tehran, Iran. Tourism Management Perspectives, 29, 41 – 47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.10.007

Gotsi, M., & Wilson, A. M. (2001). Corporate reputation management: “living the brand”. Management Decision, 39(2), 99 – 104. https://doi.org/10.1108/eum0000000005415

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., &Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53-60. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y37qq4pe

Hsu, C. H. C., Oh, H., & Assaf, A. G. (2011). A customer-based brand equity model for upscale hotels. Journal of Travel Research, 51(1), 81 – 93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510394195

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1 – 55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Israeli, A. A., & Uriely, N. (2000). The impact of star ratings and corporate affiliation on hotel room prices in Israel. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 2(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/146735840000200107

Jöreskog, K. G., Olsson, U. H., & Fan, Y. W. (2016). Multivariate analysis with LISREL. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Karunaratne, W., & Jayawardena, L. (2011). Assessment of Customer Satisfaction in a Five Star Hotel - A Case Study. Tropical Agricultural Research, 21(3), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.4038/tar.v21i3.3299

Kimpakorn, N., & Tocquer, G. (2009). Employees' commitment to brands in the service sector: Luxury hotel chains in Thailand. Journal of Brand Management, 16(8), 532 – 544. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.bm.2550140

Ladhari, R. (2009). A review of twenty years of SERVQUAL research. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 1(2), 172-198. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566690910971445

LaRock, H. (2018, April 20). How Are Hotels Star Rated? Travel Tips. USA Today. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yyma8xtj

Lollar, C. (1990). The hotel rating game. Travel and Leisure, 20(7), 64–67.

Marukatat, S. (2018, August 29). Thailand ranks 10th most popular for global visitors. Bangkok Post. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yyhpv8zl

Mattsson, J. (1994). Measuring performance in a first class hotel. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 4(1), 39 – 42. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604529410796053

Mingkhwansakul, C., & Rungsawanpho, D. (2018). Quality of service of hotel and lodging businesses in Samutsongkram Province, Thailand. Proceedings of the International Interdisciplinary Conference, Vienna. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yxv6u8jr

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. The Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20-38. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252308

Narangajavana, Y., & Hu, B. (2008). The relationship between the hotel rating system, service quality improvement, and hotel performance changes: A canonical analysis of hotels in Thailand. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 9(1), 34 – 56. https://doi.org/10.1080/15280080802108259

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403-441. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yy5mjwy9

Ratner, B. (2009). The correlation coefficient: Its values range between +1/−1, or do they? Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing, 17(2), 139 – 142. https://doi.org/10.1057/jt.2009.5

Sanyal, A. (2008, June 2). Hotel Classification: The STAR Categories. Personal Blog. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y2zusvvd

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66(4), 507-514. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02296192

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Routledge.

Seeman, E. D., & O'Hara, M. (2006). Customer relationship management in higher education: Using information systems to improve the student-school relationship. Campus-Wide Information Systems, 23(1), 24 – 34. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ807505

Shoemaker, S., & Lewis, R. C. (1999). Customer loyalty: the future of hospitality marketing. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 18(4), 345 – 370. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4319(99)00042-0

Singh, H., Saufi, R. A., Tasnim, R., & Hussin, M. (2017). The relationship between employee job satisfaction, perceived customer satisfaction, service quality, and profitability in luxury hotels in Kuala Lumpur. Prabandhan: Indian Journal of Management, 10(1), 26 – 36. https://doi.org/10.17010/pijom/2017/v10i1/109101

Skogland, I., & Siguaw, J. A. (2004). Are your satisfied customers loyal? Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 45(3), 221-234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010880404265231

Thailand Standards Hotel Directory 2017. (2017). Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y3p3ujbu

US remains top source of Thailand's hotel guests. (2019, June 13). Bangkok Post. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/y65j97xb

Voerman, L. (2003). The export performance of European SMEs. Doctoral dissertation. The Netherlands: Labyrint Publication. Retrieved from https://www.rug.nl/research/portal/files/2974215/c4.pdf

World Travel & Tourism Council. (2017). WTTC report, Thailand in world top ten for tourism growth. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yyxodpz8

Zeba, F. & Ganguli, S. (2016). Word-of-mouth, trust, and perceived risk in online shopping. International Journal of Information Systems in the Service Sector, 8(4), 17 – 32. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijisss.2016100102

1. Faculty of Administration and Management, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang (KMITL), Bangkok, Thailand, e-mail: 56611250@kmitl.ac.th

2. Faculty of Administration and Management, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang (KMITL), Bangkok, Thailand, e-mail: drpuris.s@gmail.com

[Index]

revistaespacios.com

This work is under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 International License