Vol. 41 (Number 06) Year 2020. Page 10

Vol. 41 (Number 06) Year 2020. Page 10

PHILOMINRAJ, Andrew 1; BERTILLA, Maria 2 & RANJAN, Ranjeeva 3

Received: 09/10/2019 • Approved: 17/01/2020 • Published: 27/02/2020

3. Result and Analysis of Data

ABSTRACT: This empirical study based on learner centred approach promotes participatory learning as an appealing classroom method to foster English language teaching. Pretested questionnaires to 504 students along with a survey, taking into account several variables, were conducted. Data collected was measured and information from those instruments was analyzed. The results indicate that participatory learning is a learning through actively engaging, participating, constructing knowledge, which are all essential parts of the overall experiences that the learners gain towards their process of language learning. |

RESUMEN: Este artículo empírico basado en el enfoque centrado en el alumno promueve el aprendizaje participativo como un método atractivo de aula para fomentar la enseñanza del idioma inglés. Cuestionarios previamente probados y una encuesta, considerando múltiples variables, fueron aplicadas a 504 estudiantes. Se midieron los datos recopilados y se analizó la información de esos instrumentos. Los resultados indican que el aprendizaje participativo es un aprendizaje a través del involucramiento activo, la participación, la construcción del conocimiento, todos los que son partes esenciales de las experiencias generales que los alumnos obtienen hacia su proceso de aprendizaje de idiomas. |

Learning must be conceived as a meaning-construction process. In order to achieve such significant learning, the process must, first of all, be an active one, and then, it must be a constructive one. In other words, the basic activities in the process of knowledge creation must be oriented towards construction of meanings for the subjects themselves. Therefore, it is necessary to develop new teaching strategies providing learners with tools to build their own body of learning strategies and thus contributing towards their integral learning.

The general beliefs about teaching methodologies are that they:

a) make it possible to adequately develop those competences pertaining to the module the learner has enrolled in;

b) promote active participation by learners in the teaching and learning process;

c) reinforce the autonomous component in learning;

d) facilitate the integration of theoretical contents which can later be applied to the professional field; and

e) promote teamwork and collaborative learning. These aspects are amply built into the method of Participatory leading to the learning of English language.

Participatory learning has emerged in the recent years as a significant contribution towards English language Education. It is also referred to as Collaborative learning or Cooperative learning. Resta & Laferriere (2007) quoting Ted Panitz clearly distinguishes between the terms collaborative and cooperative in the following manner:

Collaboration is a philosophy of interaction and personal lifestyle where individuals are responsible for their actions, including learning and respect the abilities and contributions of their peers… In the Collaborative, model groups assume almost total responsibility whereas cooperation is a structure of interaction designed to facilitate the accomplishment of a specific end product or goal through people working together in groups.

Slavin (2014) refers to “Cooperative learning as a teaching method in which students work together in small groups to help each other learn academic contents”. There are researchers, such as Hiltz (1998) and Johnson and Johnson (2001) who see “little benefit in trying to tease out differences in meaning between the two words”. Collaboration or cooperative has become a twenty-first century trend. The need in society to think and work together on issues of critical concern has increased shifting the emphasis from individual effort to group work, from independence to community. Albeit the terms, the theoretical background based on the philosophy of Participation is taken into consideration in this research as this method creates an environment in which learners and teachers, learners and learners are teaching and learning from each other in an equitable way by incorporating principles of learner centeredness into their programs and curriculum.

Haryani Haron et al (2017) define Participatory learning as

Self-directed learning and uses on problem-solving style and learner engages in learning community. Participatory learning is a learning through actively engaging, participating, constructing knowledge, and participate with a learning experience through collaborative learning, co-learning and engagements. In participatory learning, learners as learning center therefore, reciprocal processes among learners are vital to produce more and strong relationships to executed learning activities for continuous learning by produce knowledge, harvesting knowledge to produce more new ideas and contribute back to community. This promotes the equality in learning, overcome shyness or uncomfortable to discuss in face to face gives each participates have the same opportunity to express knowledge and sustainable development in education field.

In a similar note, the California Department of Education (2001) expresses that

Most participatory approach involve small, heterogeneous teams, usually of four or five members, working together towards a group task in which each member is individually accountable for part of an outcome that cannot be completed unless the members work together; in other words, the group members are positively interdependent.

Balkcom (1992) also coincides in defining Participatory learning as

A successful teaching strategy in which small teams, each with learners of different levels of ability, use a variety of learning activities to improve their understanding of a subject. Each member of a team is responsible not only for learning what is taught but also for helping team mates learn, thus creating an atmosphere of achievement.

The idea of participation refers to the action of taking part in activities and projects, and the act of sharing in the activities of a group. The process of participation fosters mutual learning. The participatory learning strategy has its background theory in the Behaviorism as well as in Cognitive and Social Psychology. Collaboration is a useful tool used within participatory culture as a desired educational outcome. This tool leads to working effectively and respectfully with diverse teams, exercising flexibility and a willingness to make compromises to accomplish a common goal, and assuming shared responsibility for collaborative work while at the same time appreciating individual contributions.

Participatory learning is a method for learning about and engaging with learners (Ameri-Golestan & Alhossaini, 2017). It offers the opportunity to go beyond mere consultation and promote active participation of learners in the issues and interventions that shape their lives. It also enables negotiation of many aspects between teachers and learners, and learners and learners of what and how one learns that include objectives, knowledge, skills and attitudes. According to Nunan (1988), “a learner centered curriculum contemplates a participatory effort between teachers and learners. They are closely involved in the decision making process regarding the content of the curriculum and how it is taught”. In today’s context of language learning it is not so much that the learner remains passive and the teacher plays an active role in making the learner learn, rather it is a mutual effort where each one plays their role towards the teaching and learning process. Referring to Paulo Freire researchers Rugut and Osman (2013) state that education becomes a collective activity, a dialogue between participants rather than a 'top-down' one-way lecture from one person for the benefit of the other. In saying this Freire did not intend to create conditions where learner’s knowledge, feelings and understanding should go unchallenged or for the teacher to step back as a mere facilitator. Furthermore, he insisted that learners do not enter into the process of learning by memorizing facts, but by “constructing their reality in engaging, dialoging, and problem solving with others” (1970).

Participatory learning is proposed as one of the best practices towards language learning since it encourages learners to learn about learning, to learn better and to increase their awareness about language, and about self, and hence about learning. It encourages developing metacommunicative as well as communicative skills. It leads to confront and come to terms with the conflicts between individual needs and group needs, both in social, procedural terms as wells as linguistic, content terms. Participatory learning helps to realize that content and method are inextricably linked, and to recognize the decision-making tasks themselves as genuine communicative activities.

On studying the current situation of the learners, José Arostegui Plaza (2006) says that they are “simply reduced to passive listening, conditioned to the completion of the curriculum and the task imposed by the teachers”. This dichotomy from what is spelt as discourse and what is done in classrooms has led him to consider various models of learner participation towards achieving best results in learning a subject.

The first author he refers to is Dell Valle (1998) who identifies three participatory models, each one of them associated with different style of curriculum. The Likert model is based on the theory of business organization, which aims to identify the specific objectives of each individual with that of the overall company. It is based on two strategies, the first one, the conversion of authority, in coordination and regulation of the entire organization. Applying this to the classroom context, the involvement of teachers and learners in decision making increases the dedication towards the proposed objectives or goals. The second strategy is the teamwork where the learners look up to the institution as their own and learn to cooperate with it in order to obtain its objectives and at the same time self-realization. In order to achieve this, communication is fostered in an atmosphere of trust, which also implies clarity of roles. In addition, strong supportive relationships are encouraged between the members, as a way of strengthening individual motivation. From the above, it is understood that the participatory model of Likert involves translating the logic of business companies to learning institutions. The concern is to promote individual values and integration within the group be it a school or company.

The second model, the non-directive pedagogy of Rogers, is drawn from clinical psychology. It is characterized as learner centered with creativity and freedom as its two pillars, leaving all the rest such as organization, methodology, schedules, etc., in the background. Participation is the principle behind the restructuring of education, which claims for a new role of teacher, characterized not for the absence of leadership, but by his or her attitude that helps towards the learners personal growth through participation.

Finally, Makarenko’s model assumes that pedagogy is not neutral. It is marked by a particular choice of man and society. According to him, education should be directed towards the integration of the individual in society, that is, the community in which he or she is defined. For Makarenko, this means, to define the essence of human being not in the individual but in social relations. The positive contribution of this model is the explicitness of the ideological character of the educative action and also the interest for the integration of the individual in society.

The above mentioned models show that in Participatory learning the role of the learner is vital for it is he who could reach the remote conditions of his learning and the teacher as facilitator to the construction of learners’ autonomy (Han, 2014). By allowing learners to take control of their activity, it implies their involvement in educational task, for it will be an initiative that comes from within each learner, thus responding to their interests and needs.

Empirical work in literacy instruction has supported the theory of Participatory learning in reading and writing to traditional instruction. Slavin (2014) found that learners working in groups participatively outperformed significantly those learners receiving traditional instruction. Participatory learning is also supported by recent research inspired by process-oriented model of second language acquisition. The question raised was; what patterns of classroom organization and types of classroom tasks are most beneficial for language acquisition. Several researchers responding to the above raised question have mentioned that the tasks, that involve learners to negotiate meaning among themselves participatively, are best suited to language development (Sanchez, 2007).

The theoretical, empirical and practical advantages of Participatory learning have been aptly summarized by Slavin (2014) in the following manner

The research done till now has shown enough positive effects of participatory learning, on a variety of outcomes, to force us to re-examine traditional instructional practices. We can no longer ignore the potential power of the peer group, perhaps the one remaining free resource for improving schools. We can no longer see the class as 30 or more individuals whose only instructionally useful interactions are with the teacher, where peer interactions are unstructured or off-task. On the other hand, at least for achievement, we now know that simply allowing learners to work together is unlikely to capture the power of the peer group to motivate learners to perform.

The traditional instructional practices referred by Slavin are Task Based Teaching (TBT) and Activity Based Teaching (ABT). The first one refers to an approach, based on the use of tasks as the core unit of planning and instruction in language teaching (Richards & Rodgers, 1986). TBT propagates self-directed learning but it still requires teachers to assist and have control over the activities and encourage the active participation of the learners. Activity method is a technique adopted by a teacher to emphasize his or her method of teaching through activity in which the learners participate and bring about efficient learning experiences. In this method, learners need to be provided with data and materials necessary to focus their thinking and interaction in the lesson for the process of analyzing the information. Teachers need to be actively involved in directing and guiding the learners’ analysis of information. A reexamination of the above mentioned practices reveals that the Participatory Learning is a Leaner Centered Approach. The tasks involve learners to negotiate meaning among themselves participatively which helps language development. The learners take control of their activity and participate in decision-making. Teachers and learners together through negotiation decide on the content that reflects the needs and necessities of the learner. In participatory learning, the learner does not learn alone but in company of a group or peers who learn together participatively. Learning is a process in Participatory Learning, which does not limit itself to the classroom; rather it goes beyond the four walls. Interactions with teachers, peers, native speakers and environment are valuable inputs that lead to the learning of English language.

As a corollary to the theoretical understanding of the present topic, a quantitative study by way of data collection, analysis and interpretation has been carried out in order to substantiate the proposal and the province of the present study. The primary data was collected from 504 students with different pretested questionnaires. The survey was conducted in ten higher secondary schools in the city of Chennai. A selection of a series of variables is taken into consideration in the survey, which is measured, and information on each one is collected to describe what is researched (Hernandez, 2003).

The survey questions contained topics concerning participatory practices. All the questions were of closed-ended model, allowing learners to choose one of the alternatives.

Table 1

Survey questions

Sl. No. |

Survey questions |

Type of question |

1. |

Do you participate in group activities in class to improve your English? |

Yes/No |

2. |

Do you like to speak in English to your friends? |

Likert Scale |

3. |

Do you feel nervous to speak in English to strangers? |

Likert Scale |

4. |

In your daily life, do you find opportunities to speak English with other persons? |

Likert Scale |

5. |

Opinion on Participatory learning practices of your English lessons |

Closed-ended questions with options |

The statistical analysis and the results of every question to the learners are presented through individual tables and for the purpose of the diagrammatical representation; a few questions are clubbed wherever it is necessary and represented through charts. The analysis and the results of the data of the survey are also followed with their interpretations.

Table 2

Sample Learners on Group

Activities to Improve English

Sl. No |

Opinion |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

1 |

Yes |

324 |

64.3 |

64.3 |

64.3 |

2 |

No |

180 |

35.7 |

35.7 |

100.0 |

|

Total |

504 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Source: Computed from field survey

Table 1 shows that 64.3 percent of the sample learners have participated in group activities in the class to improve their English, whereas the rest of 35.7 percent have replied with a no. Group activities help learners to gain skills such as interaction, reflective capacity, language use, participation, cooperation, active thinking, teamwork etc. Group activities in class foster Participatory learning that enables learners learn the language by means of interaction between peers and teachers.

Table 3

Sample Learners on Speaking

in English to their Friends

Sl. No |

Opinion |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

1 |

Always |

114 |

22.6 |

22.6 |

22.6 |

2 |

Often |

200 |

39.7 |

39.7 |

62.3 |

3 |

Rare |

125 |

24.8 |

24.8 |

87.1 |

4 |

Never |

47 |

9.3 |

9.3 |

96.4 |

5 |

No opinion |

18 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

100.0 |

|

Total |

504 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Source: Computed from field survey

Table 2 shows that 22.6 percent of the sample learners have opined as always, while 39.7 percent opined as often. 24.8 percent responded that they speak rarely in English to their friends. 62.3 percent of the sample learners’ opinion that they speak in English to their friends reflect Participatory learning through interaction between peers and others and also experiential learning using previous knowledge of language that helps them to communicate without barriers. The rest of them if introduced and exposed to the above mentioned practices will certainly benefit in learning the language.

Table 4

Sample Learners on Feeling Nervous

while Speaking in English to Strangers

Sl. No |

Opinion |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

1 |

Always |

56 |

11.1 |

11.1 |

11.1 |

2 |

Often |

89 |

17.7 |

17.7 |

28.8 |

3 |

Rare |

98 |

19.4 |

19.4 |

48.2 |

4 |

Never |

246 |

48.8 |

48.8 |

97.0 |

5 |

No opinion |

15 |

3.0 |

3.0 |

100.0 |

|

Total |

504 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Source: Computed from field survey

Table 3 shows that 11.1 percent have responded as always, 17.7 percent opined as often, 19.4 percent said as rare and 48.8 percent of the sample learners’ have answered in the negative with regard to their feeling of nervousness while speaking in English to strangers. Learners’ not feeling nervous indicates their experience and knowledge of L2 and L1, the environment that favors exposure, and as observed during the survey, it also confirms the participative attitude of the learners’ to interact with others.

Table 5

Sample Learners on Finding

Opportunities to Speak in English

Sl. No |

Opinion |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

1 |

Always |

193 |

38.3 |

38.4 |

38.4 |

2 |

Often |

180 |

35.7 |

35.8 |

74.2 |

3 |

Rare |

98 |

19.4 |

19.5 |

93.6 |

4 |

Never |

21 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

97.8 |

5 |

No opinion |

12 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

100.0 |

|

Total |

504 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Source: Computed from field survey

As evident from Table 4 on the question of finding opportunities to speak in English with other persons, 38.4 percent responded with always and 35.8 percent with often 19.4 percent answered that they get rarely the opportunity whereas 4.2 percent said never. The majority (74.8 percent combining always and often) of the sample learners, finding opportunities to speak in English with other persons indicates the contribution of the environment that favors speakers of English. This opportunity also fosters participation of the learners to interact positively with other speakers and thus strengthen their communicative skills of the English language.

Table 6

Sample Learners on Participatory Learning

Practices of their English Lessons

Sl. No |

Opinion |

Frequency |

Percent |

Valid Percent |

Cumulative Percent |

1 |

Group discussion |

102 |

20.2 |

20.2 |

20.2 |

2 |

Role plays |

49 |

9.7 |

9.7 |

29.9 |

3 |

Guest interaction |

35 |

6.9 |

6.9 |

36.8 |

4 |

Drama |

54 |

10.7 |

10.7 |

47.5 |

5 |

Debates |

43 |

8.6 |

8.6 |

56.1 |

6 |

Projects |

22 |

4.4 |

4.4 |

60.5 |

7 |

Competitions |

37 |

7.3 |

7.3 |

67.8 |

8 |

Class discussion |

82 |

16.3 |

16.3 |

84.1 |

9 |

Quiz |

59 |

11.7 |

11.7 |

95.8 |

10 |

Forums |

21 |

4.2 |

4.2 |

100.0 |

|

Total |

504 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Source: Computed from field survey

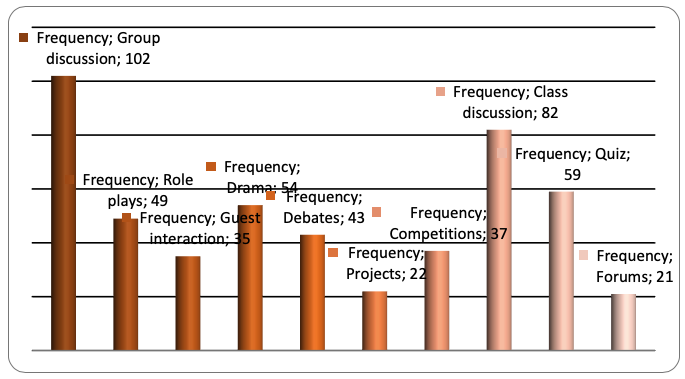

The opinion of sample learners’ on participatory learning consisting of group discussion, role plays, guest interaction, drama, debates, projects, competitions, class discussion, and quiz forums is given in Table 5. Group discussion (20.2 percent) and class discussion (16.3) have been highly preferred by the sample learners in response to the participatory learning practices. These practices create language environment, offer language input, establish a dynamic learning pattern, and enable learners to go beyond consultation to foster mutual learning.

Chart 1

Sample Learners on Participatory Learning

Practices of their English Lessons

Source: Based on Table 5

The quantitative study on exploring the importance and the use of Participatory learning amidst students in the city of Chennai clearly indicates that teaching here is no longer “taking up of the predetermined problem in a ritually defined setting” (Hiltz,1998). Results from the survey also throw light on the fact that learning situation has to be creative and exploratory. Learners’ interest has been on sharing knowledge through skill exchanges with the teacher, and the environment.

The learners’ learning experience as deduced from the survey is also close to Freirean problem-posing model. Dialogue is the chief characteristic of the model. Learners are teachers as much as teachers are learners as per this model. The content of education is neither a gift nor an imposition rather it is a presentation of issues relevant to every individual learner.

Participatory learning is a method of learning, which also encompasses engaging with learners. It offers the opportunity to go beyond mere consultation and promote active participation of learners on the issues and interventions that shape their lives. The results show that participatory learning is one of the best practices to foster language learning since it encourages learners to learn about learning, to learn better and increase their awareness about language, about self and hence about learning.

Ameri-Golestan, A., & Nezakat-Alhossaini, M. (2017). Long-term effects of Collaborative Task Planning vs. Individual Task planning on Persian-Speaking EFL Learners’ Writing Performance. Research in Applied Linguistics, 8(1), 146-164. doi:10.22055/rals.2017.12617

Balkcom, S. (1992). Cooperative learning. Retrieved from http://www.ed.gov/pubs/OR/ConsumerGuides/cooplear.html.

California Department of Education. (2001). Visual and performing arts content standards for California public schools. California: CDE Press. Retrieved from https://www.cde.ca.gov/be/st/ss/documents/vpastandards.pdf

Del Valle, A. (1998). Makarenko, Rogers, Likert: tres modelos de participación. Valencia: Promolibro.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. NewYork: Seabury Press.

Han, L. (2014), Teacher's Role in Developing Learner Autonomy: A Literature Review, International. Journal of English Language Teaching, 1(2). doi:10.5430/ijelt.v1n2p21

Haryani, H., Noor H. N. A., & Afdallyana, H. (2017). A Conceptual Model Participatory Engagement within E-Learning Community. Procedia Computer Science, 116, 242-250. doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.10.046

Hernández et al., (2003). Metodología de la investigación. Editoral McG.

Hiltz, R.S (1998). Collaborative learning in asynchronous learning networks, building learning communities. Retrieved from http://eies.njit.edu/~hiltz

Illich, I. (1970). Deschooling society. London: Calder & Boyars Ltd.

Johnson, D., & Johnson, J. (2001). Cooperative learning. Retrieved from http://www.clcrc.com/pages/cl.html

Kaewpet, C. (2009). Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 6(2), 209 -220. National University of Singapore Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/1560938/A_Framework_for_Investigating_Learner_Needs_Needs _Analysis_Extended_to_Curriculum_Development?auto=download

Laal, Marjan & Laal Mozhgan, (2012). Collaborative learning: what is it? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 491-495. doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.092

Nunan, D. (1988). The Learner centered curriculum. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Resta, P., & Laferrière, T. (2007). Technology in Support of Collaborative Learning. Educ Psychol Rev, 19, 65-83. doi 10.1007/s10648-007-9042-7

Plaza, J. L. A (2006). La Participación del alumnado en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Participación Educativa, 2, 44-50. Retrieved from http://wpd.ugr.es/~arostegu/?p=97

Richards, C. J, & Rodgers, S. T. (1986). Approaches and methods in language teaching. (2nd Ed). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rugut, E. J. & Osman, A. A. (2013). Reflection on Paulo Freire and Classroom Relevance. American

International Journal of Social Science, 2(2).

Sánchez, C. A. (2007). A Learner-Centered Approach to the Teaching of English as an L2. Revista de filología inglesa. 28. 189-196. Retrieved from https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/2535996.pdf

Slavin, R. (2014). Cooperative Learning and Academic Achievement: Why Does Groupwork Work? Anales de psicología, 30(3), 785-791. doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.201201

1. Professor of English and Director of Doctoral program in education at Universidad Católica del Maule, Talca, Chile. Contact e-mail andrew@ucm.cl

2. Assistant Professor of English working at Queen Mary’s College in Chennai, India. Pursuing doctorate in ELT. Contact e-mail bertilla.maria006@gmail.com

3. Postdoctoral researcher at Universidad Católica del Maule, Talca, Chile. Contact e-mail ranjan@ucm.cl

[Index]

revistaespacios.com

This work is under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 International License