Vol. 41 (Number 04) Year 2020. Page 15

Vol. 41 (Number 04) Year 2020. Page 15

GUTIERREZ, Ronald S. 1; MCDOUGALD, Jermaine S. 2 & ROZO, Hugo A. 3

Received: 03/10/2019 • Approved: 26/01/2020 • Published: 13/02/2020

ABSTRACT: The study explored the perception of Colombian undergraduate students regarding the use of Facebook as a communication tool and interaction in the classroom. The findings suggest that Facebook in the classroom is fun, practical and an effective communication tool that fosters interaction and offers greater advantages in terms of reminders and ease of use while accompanying the training process and independent work of the students. All the while providing realistic learning activities that go beyond the confines of a classroom. |

RESUMEN: El estudio exploró la percepción de estudiantes colombianos de pregrado respecto al uso de Facebook como una herramienta de comunicación e interacción en el salón de clase. Los hallazgos sugieren que Facebook en el salón de clase es divertido, práctico y como tal, Facebook es una herramienta de comunicación efectiva que fomenta la interacción y ofrece grandes ventajas en términos de recordatorios y facilidad de uso mientras que se acompaña el proceso de aprendizaje y el trabajo independiente de los estudiantes. Facebook brinda grandes posibilidades para generar actividades de aprendizaje realistas que van más allá de los límites de un salón de clase. |

Human beings from the beginning have interacted with the medium intuitively and by nature, forging processes of communication with their environment. It is an individual who creates, discusses, argues, thinks and learns in a collective (Capello & Faggian, 2005) or as a social being (Cicourel, 1974; Pons, 2010). The networked society, coupled with the capacity for human communication and the different possibilities that bridle the existing platforms create immaterial spaces of learning, collaboration and research in which there are no barriers, potentializing processes of collaborative writing, collaborative work, research together and creating different spaces or environments, where the process of learning and teaching occurs in a non-traditional way according to Picciano, Dziuban, & Graham (2014). However, these societies are not the future; but mere contemporary moments that are individual go through, but it must be understood that we all live in an ecosystem of constant and active learning that present opportunities for interaction and communication.

At present, social networks offer a series of services that are attractive to be incorporated into the teaching-learning processes and are outlined as a suggestive or alternative option that allows the active participation of each of the actors involved in the communication process in the classroom. In turn, it provides versatility and immediacy, positioning itself as the preferred channel of communication between students and teachers (Gómez, Roses, & Farias, 2012). In this sense, social networks (SNs, hereafter) are composed of social actors and the interactions that occur between them. A SN is a dynamic exchange between people, groups, and institutions in different contexts and situations, they are open and flexible systems, which are self-managed and are created in real-time and permanently, with a clear objective of communication between the actors that integrate it (Caldevilla, 2010).

Taking into account the benefits described thus far, it could be said that a new educational scenario mediated by digital social networks has been configured, which has been decisive and innovative in the way it has transformed the interactions and forms to relate to the different actors that compose them (Walther & Jang, 2012). This, however, has strengthened the capacity of human beings to adapt, share and understand information, generating new knowledge through interconnected communities in a changing and ubiquitous environment. The process of generating and acquiring knowledge today is carried out through massification and visibility. Since the process is understood as a social phenomenon, which is generated spontaneously but intentionally, from any device and place, through the Internet and the supply of platforms that the network offers, as a means of communication that people have incorporated into everyday life in a natural way (Tello, 2007). In a networked society, it is common for most people to carry out activities such as sending messages, watching videos and photos, playing music, sharing locations, playing online and chatting through these platforms, considering that their reach is incalculable according to Puerta-Cortés & Carbonell (2013). Furthermore, the Pew Research Center (2019), concluded that the use of social networks, specifically Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, and Pinterest, has remained intact since 2016, the only network that has grown is Instagram. This, however, suggests that studies that promote social networks as an educational medium or platform and validate perceptions that have been built in recent years are still necessary.

Defining social networks from the perspective of Boyd and Ellison, (2007) can be referred to as internet sites that allow people to make connections with different individuals and even make new friends in a virtual way, and share content, interact, create groups on related interests: work, study, entertainment, relationships, among others (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). From this point of view, it is important to clarify as Gómez et al., (2012) who claim that these organizations, understood as web-based services, promote the possibility of building connections, articulating and interacting with the environment by being an affordable, interactive, meaningful and dynamic system. However, they are constructed with everyone acting as active participants, constituting them as platforms that favor several types of communicative exchange between the teacher and student in the training area.

In classroom practices, social networks play a lead role in incorporating what society is already using as part of their daily lives, especially in undergraduate students who have access to different devices and who spend much of their time browsing and interacting in these networks (Cerdà & Planas, 2011; Moore-Russo, Radosta, Martin, & Hamilton, 2017). McDougald (2013) claims that by using social networking sites in the classroom, it provides learners with a more comfortable and natural environment to communicate while fostering the learning process. It is time to create networks for educational purposes, or better, to make a presence in the networks with academic information. However, since learning must respond to situations that take place in the real world, where learning mainly works with information, that overflows in the social networks, thereby allowing the educational community to be an active agent in these networks with the responsibility of filtering information, exploiting the communication potential for academic purposes within the classroom but with a global reach (Vidal, Martínez, Fortuño, & Cervera, 2011).

There is a lot to be said about Facebook's use for academic purposes, especially in higher education (Dennen & Burner, 2017; Manca & Ranieri, 2013; Roblyer, McDaniel, Webb, Herman, & Witty, 2010). Since its start in 2004, Facebook has become one of the world's most popular and favorite social media networks, with 2,167 million active users in January 2018 (Statista, 2018). Yet, Selwyn (2007) reminds us that Facebook has become very popular behind the scenes for higher educational institutions. Yet, this social media tool has been adopted by many American universities and colleges (Arrington, 2005; Bosch, 2009; Irwin, Ball, Desbrow, & Leveritt, 2012) as a result of being adaptable for educational purposes. Due to its vast features, Facebook can be easily adapted to an educational context, with features such as email bulletin boards, instant messaging, video, chat, the ease of posting pictures or videos and integration with other third-party software. Alhazmi, Rahman, Computing, & Johor (2013) remind us that social networking sites (SNSs, hereafter) such as Facebook "provide a variety of opportunities to facilitate student learning, allowing them to interact, communicate, collaborate and share content for educational purposes” (p. 32), also echoed by Alexander (2005). Furthermore, Facebook caters to and supports educational objectives as well as on the spot communication, online collaboration, and the ability to share between students and faculty (Eteokleous, Ktoridou, Stavrides, & Michaelidis, 2012).

Several studies (Labus, Despotović‐Zrakić, Radenković, Bogdanović, & Radenković, 2015; Magogwe, Ntereke, & Phetlhe, 2015; Pérez, Araiza, & Doerfer, 2013), demonstrate the potential of this tool (Facebook) to be integrated into the classroom, which has as a pretext to develop a different learning experience in which it is concluded that students can participate actively, work collaboratively, generate a critical attitude based on the socialization of the tasks using the network as a mechanism of communication with their peers and the teacher (Wankel, 2012). Therefore, the time has come to occupy a space in the student's environment using this type of platform, ensuring that through empirical evidence it will be possible to demonstrate and determine the effectiveness and perception on part of the student to make possible adjustments and to replicate these initiatives (Manca & Ranieri, 2013).

Considering that the current study involves the perceptions of students in higher education, it is essential to understand how they perceive Facebook in terms of their academic performance. These results may vary from country to country or even institutions within the same country (Junco, 2012). Nevertheless, this information is vital in the sense that it can play a huge factor in the overall teaching and learning process and makes a difference in terms of communication, interaction, and even collaboration using SNS and digital technologies.

Communication is a process by which information is transmitted and received in the form of a message between human beings (Richards & Schmidt, 1983), this exchange is carried out with the aim of achieving an understanding and operation regarding the process of interaction. This exchange always occurs bi-directionally, the moment a person speaks and the other listens, in the space where one person writes and the other reads, regardless of whether it is synchronous or asynchronous. Communication has occurred spontaneously in humans since its inception, because of the need for people to interact with their environment.

Obtaining clarity about the communication process, communication is understood in the classroom, the precise event that is carried out with the members of a given community with a pedagogical emphasis on the natural and daily act, generating and enabling the interaction between teacher-student, by way of a discourse that has any intention of transmitting the knowledge to all the actors involved in the process (Smart & Marshall, 2012). Undoubtedly, a traditional process still prevails in the educational practices of the 21st century. This process can be altered in its mediation or transmission channel thanks to the different alternatives that information, communication, and technologies (ICTs) currently offer, transferring the learning environment to different non-formal spaces in which the student is immersed and responds to different learning styles (Kirkup & Kirkwood, 2005). Both education and communication are living processes that change and reciprocally adapt. Therefore, if the educational process has a change, it will affect the way communication happens (Moallem, 2015).

De Oliveira (2009), claims that education articulates communication as an intrinsic process of a human being and education in a collectively using an egalitarian dialogue between teacher-student, which occurs in an environment and in a determined context (2009), this interdisciplinary process suggests that today considering the cultural change in which society is found, it is impossible to think that education and communication are different processes. On the contrary, it really makes sense when (communicators - teachers) and (receivers - students), both teach and learn at the same time, promoting collaborative learning under a dialogic dimension, through educational activities (González P., 2013).

The aforementioned point of view ties into Educommunication, which is a continuous and bilateral training process, in which both teachers and students have a relation in an academic environment as well as their cultural transformation to adapt knowledge, communication, and information to the changing environment. Communication in the 21st century has been modified and transformed by information and communication technologies, messages are instant, short and networked, generating social, political, economic and educational changes that are conceived as Educommunication, in which it is a must to "consider communication not as a mere mediatic or technological instrument but above all as a pedagogical component" (Kaplún, 1998, p. 158). In this sense, the teacher in using ICTs should reflect on the pedagogical strategies of such (Chiappe, Rozo, Menjívar, Corchuelo, & Alarcón, 2016) so that, communication will favor learning depending on the setting and what is desired.

The communicative process in virtual learning environments remains the same since the experience of the environment is one that offers a different feeling of the process, altering the means and channels, opening an indeterminate range of possibilities (Chen, 1999). These channels and media make the creation of digital environments viable in which the training process is currently being carried out, under unusual methodological perspectives, ranging from individual learning to collaborative learning and where the transmission of information generates the construction of information and knowledge.

Virtual learning environments understood as interactive spaces where the teaching-learning process is carried out and must be supported by tools that respond correctly to the communicative and even more so to the educational challenges. How can one sense the communicative tools are key in these environments? Well, they must be incorporated precisely and must be known by the teachers who implement them, with clear pedagogical intentionality that favors the acquisition and collaboration of knowledge. Furthermore, communicative methods should be provided for the social interaction of all participants and the generation of knowledge on the part of the participants.

According to Hill and Hannafin (2001), the teacher’s role should be significant, as well as be responsible to potentiate the student's communicative competence, so that communication within the learning environment transcends, thereby generating participation from students and the teacher as senders and receivers of information. This, in turn, results in an excellent communication process that benefits the learning objectives and as such the whole educational process.

The current study follows a mixed-method research process using the grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, 2008) where the data is triangulated. Furthermore, to determine the uses of Facebook as a communication tool for academic purposes an online survey was designed to measure: the use of Facebook, advantages, and disadvantages of FB as an educational tool, delivery of homework, FB as a means of communication and perceptions about sharing personal information amongst teachers and classmates. The survey was organized into three sections demographics, quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative - (4 multiple-choice questions) Qualitative - (8 opened-ended questions). Twelve questions covered important aspects of the use of Facebook as a communication tool for academic purposes as discussed in the literature review. The questions addressed in the current study are as follows in Table 1:

Table 1

Questions used in the study

Quantitative Questions |

Q1. Using Facebook as an educational tool resulted… |

Q2. Delivering class activities through the Facebook group was … |

Q3. Facebook as a means of communication resulted … |

Q4. According to Facebook use in class, I consider that … |

Qualitative Questions |

Q5. How do you consider that Facebook has supported the learning process within the subject? |

Q6. How can a tool like Facebook improve the learning process of the class? |

Q7. What advantages do you find in using Facebook as an educational tool? |

Q8. What disadvantages do you find in using Facebook as an educational tool? |

Q9. What is your opinion regarding the delivery of the tasks through the Facebook group? |

Q10. What is your opinion of using Facebook as a means of communication? |

Q11. What is your opinion about the fact that the teacher has access to the public content of your Facebook profile? |

Q12. What is your opinion about the fact that you have access to the public content of the teacher's Facebook profile? |

At the beginning of the implementation, a Facebook group was created where undergraduate student participants were invited, indicating that this was an additional communication channel to the usual ones (email, LMS, virtual platform, among others). All students were required to join the group. As a class strategy, it was suggested that the tasks be delivered mainly in digital format, which was documents, mind maps, infographics, posters or videos. All materials were easily publishable in the Facebook group. For each task that was assigned during class, the teacher started a new post, where the students were asked to respond to that same post. The students were not supposed to deliver the task by generating a new post, but merely respond to the teacher's initial post to preserve the thread and discussion of the topic could be easily tracked and monitored. According to Wang, Woo, Quek, Yang, and Liu (2012), this is one of the ways in which Facebook provides a way to organize communication with students.

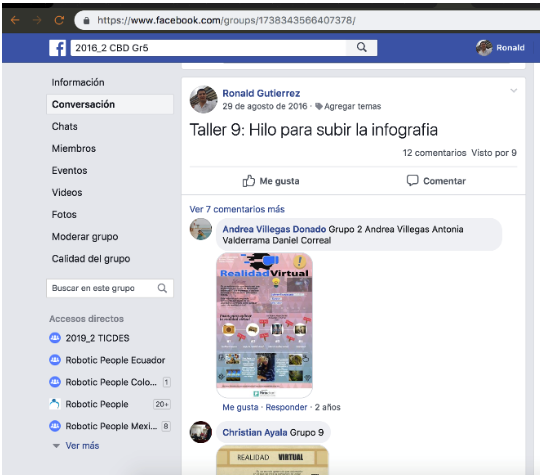

In some cases, the teacher asked the students to observe and respond to their classmates and indicate if they “liked” the content or if they made constructive comments. It is important to note that these deliveries could also be made via email or the traditional institutional LMS virtual platform, however, for the purposes of the investigation; the decision was made to make all deliveries through the Facebook group. Similarly, when the teacher wanted to communicate with the students, such as extending a delivery date of a task, or some additional explanations or bibliography, this was also done through the Facebook group. In addition, students could post, with questions, addressing the teacher or their peers, turning that specific post into a small forum about the topic raised as seen in Figure 1. Not only could academic questions be asked, but also doubts regarding overall classroom logistics or management such as dates of deliveries, evaluations and so on.

Figure 1

Screenshot Facebook group interaction

Many of the participants were aged 16 to 20. The participants were all Colombian higher education students, varying in terms of majors, all from the same university. There were 19 undergraduate majors or programs that participated in the study, for a total of 53 student participants (n=53).

The study took place over a 12-month period, two academic terms of 16 weeks each. The analysis was performed holistically considering the instruments applied. It was not necessary to establish categories of analysis, however, in each question, the contribution of the same objective that orientated the research was observed. This allowed a cross-sectional and integral analysis for each of the questions and then a triangulation between the findings.

Q1: How do you consider that Facebook has supported the learning process within the subject? FB "facilitates" communication between teacher-student, student-student, and student-teacher communication. Participants also claimed the delivery of documents and assignments, supported their efforts in the classroom and that FB helped them to remember what needed to be done in real-time, as displayed in Table 2. On another note "utility" also came to light, being described as "fast", and more practical than conventional means, thereby making FB "more useful and practical" than traditional means for communication in the classroom. These results coincide with other studies that have been conducted regarding FB to support the teaching and learning process as seen by (Akbari, Eghtesad, & Simons, 2012; Irwin et al., 2012; Jahan & Ahmed, 2012; Roblyer et al., 2010).

Table 2

Frequencies on Facebook Supporting the learning process

Purpose |

Frequency |

|

Facilitates |

Communication |

7 |

Communication between teachers & students |

12 |

|

Access |

||

Loading documents |

14 |

|

Following instructions & not forget assignments |

1 |

|

Deliver assignments |

1 |

|

Utility / usefulness |

Rapid and Fast |

10 |

More useful to stay connected |

||

More useful for teens & young adults than emails |

1 |

|

More practical |

1 |

|

Really good tool |

1 |

Q2: How can a tool like Facebook improve the learning process in the class? The results all point to the fact that FB could improve the learning process in the classroom; more than six distinct categories were discovered as seen in Table 3. Heading the list was being able to "share" academic documents; communicating to the group in "real-time", thus making communication much more "practical, familiar and easily accessible", as well bidirectional. Participants reported that FB made learning "easier", generating confidence between teacher and student and brought both teachers and students together for a more dynamic and interactive class environment.

Table 3

Frequencies on Facebook improving

the learning process in the class

Purpose |

Category |

Frequency |

Improves |

The way in academic documents are shared |

7 |

Communication between teacher-student |

12 |

|

Communication making it more practical, familiar and easily accessible |

1 |

|

The learning process |

14 |

|

Communication: generates more confidence |

1 |

|

Classes: more dynamic and interactive |

1 |

|

Teacher-student relationship |

1 |

Q3: What are the advantages of using Facebook as an educational tool? Several areas arose when inquiring about if FB was an advantage in education. However, these responses were organized into 6 fundamental areas: didactics, communication, access, organization, speed and usefulness which were like areas identified by Alhazmi (2013) also very similar to the educational model developed by Mazman and Usluel (2010) where the same topics as - usefulness, ease of use, communication, collaboration, etc. – were also discovered. Nevertheless, it is evident that communication plays a huge role, as students perceive Facebook in their daily lives as well as in their academic responsibilities.

Q4. What are the disadvantages in the use of Facebook as an educational tool? It comes as no surprise that there are several disadvantages to Social Media Networks (SMNs) in the classroom. Now, it has been demonstrated previously, that there are an array of positive features and outcomes to the inclusion of FB in academics, nevertheless, students that participated in the study had several claims as to why practitioners should be cautious or establish clear strategies, objectives, and essential agreements when including this tool in the classroom. Some of the areas found were distraction and access.

(FB) tends to distract the students a lot, Questionnaire, Q 4, Participant No. 5 Sometimes one gets distracted by the other things on Facebook, Questionnaire, Q4, Participant 6 We can be distracted by other things that this medium offers, Questionnaire, Q4, Participant No. 18 |

Most respondents agreed that Facebook would be a distraction in the classroom; therefore, clear guidelines would need to be designed and introduced into the classroom, so that learners are clear as to how it could and/or should be used. Regardless, of the tool that is used in the classroom, there will always be some form of distraction. Often times, the distractions can be avoided or diminished by establishing a clear connection between the tool and the pedagogical goal/objective. Additionally, previous training on how to use the tool for classroom purposes would also aid in lowering the number of distractions that arise. In essence, the more learners are comfortable with the tool and understand why the tool, in this case, FB is being used, the more connected learners will be, thereby keeping learners focused.

Based on the quantitative part of the instrument applied, some perceptions were obtained on the part of the participants, which made it possible to better understand in what percentage of acceptance of Facebook would be used. At the end of this analysis, an overall analysis is presented allowing researchers to understand the complete and robust perception of incorporation.

Almost all (98.2%) of the participants perceived FB to be either very funny, funny or even normal. However, when asked how they perceived FB as an educational tool, 92. 4% agreed that it would be very useful and useful, which coincides with FB being normal for learners. Now, most of the participants also felt that delivering class activities through Facebook was also considered “easy to use”, “practical” or even “interesting”. These are also indicators that FB is not far away from what students are accustomed to doing in their everyday activities. It is worth mentioning that participants are keen on the idea of FB as a means for communication, claiming it to be “practical” and even “better than email”.

It is a great source of communication. Questionnaire, Q4, Participant 1 Simple and easy, but very useful. Questionnaire, Q4, Participant 2 It is very useful, but it is important to know how it is used and with whom the information is being shared, etc. Questionnaire, Q4, Participant 5 I find it useful, accessible, and universal; however, it has a great tendency to distract the user with the large amounts of information presented infinitely. Questionnaire, Q4, Participant 6 |

Yet, none of the participants perceived the communication in FB as being invasive or impractical, but all of them agreed that it was practical, familiar and better than using emails to communicate.

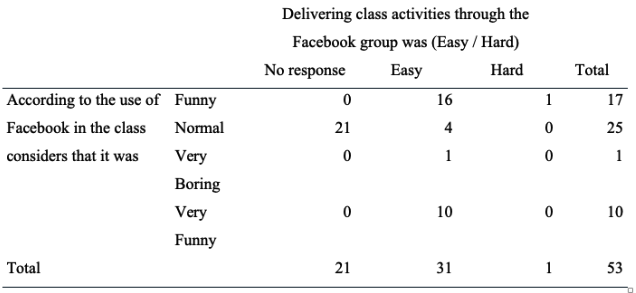

Finally, the responses were cross-referenced from questions Q1 (Use of FB as an educational Tool) and Q2 (Delivering Classes using FB), regarding the different options of Q3 (FB as a means of communication) and Q4 (Use of FB in terms of ease). SPSS generated a total of 12 different tables, of which the following tables (A, B, C,) stood out amongst the others, which are described below. In Table 4 the cross-reference revealed that 26/31 (83.8%) participants who responded to Q3, considered that the FB “is fun” or “very funny”, as well as “easy to use”. Equally, it is observed that out of the 21 (67.7%) participants that considered FB normal, only 4 answered Q3 considering it easy to use.

Table 4

According to the use of Facebook in the class considers that it was against

delivering class activities through the Facebook group was (Easy / Hard)

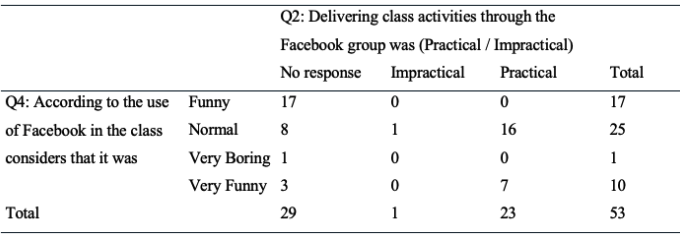

In Table 5, 23/24 (95.8%) students who answered Q4, in addition to considering FB between “normal” and “fun”, also considered it as a “practical tool” for delivery for class activities.

Table 5

According to the use of Facebook in the class considers that it was against

delivering class activities through the Facebook group was (Practical / Impractical)

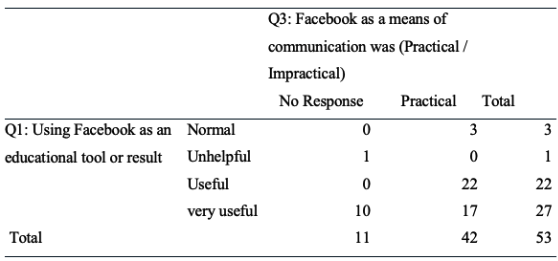

While contrasting Q1 with Q3 in Table 6, regarding the practicality of using Facebook, as a means of communication, 39/42 (92.8%) participants who answered, considered that FB, besides being useful and very useful, is also practical to use in the classroom.

Table 6

Using Facebook as an educational tool or result Against Facebook

as a means of communication was (Practical / Impractical)

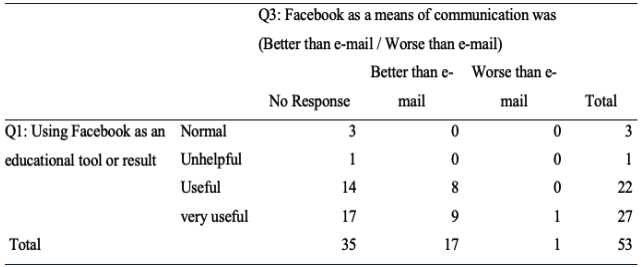

Finally, when contrasting Q1, about the use of Facebook as an educational tool, compared to Q3 regarding the use of Facebook, as a means of communication compared to email, in Table 7, 17 out of the 18 (94.4%) students who responded, indicated that they consider between useful and very useful, in addition to FB being better than the electronic mail.

Table 7

Using Facebook as an educational tool or result Against Facebook as a

means of communication was (Better than e-mail / Worse than e-mail)

Overall, after processing all of the data, both quantitative and qualitative, the results still point to the fact that FB can and could be used for academic purposes. The participants, in this study, are habitual users of FB, like many other undergraduate university students, in which they depend heavily on their mobile devices, while creating close bonds to the SMS, which coincide with Alhabash and Ma (2017, p. 3) who claim that “among college students there are seven motivations for using FB: social connection, shared identities, photographs, content, social investigation, social network surfing, and status updates.” This dependence or a bond can be seen throughout this study, in which participants constantly refer to the time spent on their devices, type of content viewed and their willingness to use their “personal space” Facebook used within an academic environment. Labeling Facebook as easy, fun, normal, practical and even better than using emails to communicate. As such, instructors using FB are at an advantage since this tool can be seen as a viable option in the teaching and learning process, where success is more prone to be achieved.

Based on the results obtained in the study, it is observed that students perceived the use of Facebook in class, as a fun and useful strategy, considering that it is a tool that they usually consult several times a day from their mobile devices and computers and they are accustomed to using it in order to communicate and interact (Gómez, Roses and Farias, 2012). In this sense, they already know how it works and it is an environment that they know how to handle, and in which they can develop their learning processes much more naturally similar to what was found by Alhabash and & Ma (2017), where learners view FB as being centered on the social value of the SMS since it is related to interacting and connecting with friends.

The use of Facebook was not only limited to generating interaction and was not merely perceived as a new channel of communication among the participants of the process, but rather to the use of the tool as a platform and a strategy to accompany the training process and independent work of the students. Participants delivered activities, left evidence, held forums, and the entire process was documented, and feedback was provided the entire time throughout the process, much like the results found by Mazer, Murphy, & Simonds (2007) and McDougald (2013) where they reported learners being more comfortable communicating and achieving learning outcomes. Nevertheless, the use of Facebook and the proposal to integrate it into the classroom as a pedagogical tool was perceived as satisfactory, since it is consolidated as a practical tool, much better than email, taking into account that the use of the platform is very simple and offers all the facilities and services (Roblyer et al., 2010). Repeatedly, learners have expressed the need to be more practical with classroom assignments and tasks. The results that arose from the current study, also echoed Roblyer et al. (2010) in terms of efficient communication, easy to use tools as well as realistic learning activities that extend beyond the confines of the classroom.

Among the advantages identified in the study are the reminders of tasks in real-time, the possibility of observing the deliveries of classmates, the publication time record, student-teacher, and student-student communication and everything in a scenario that generates confidence and allows a perception of greater dynamism from the perspective of the student. The disadvantage of FB is the invasion of privacy, due to the fact that the teacher/instructor could see all photos, comments, and all the public information posted by their students, but nevertheless some participants mentioned, that they are aware that each one is responsible for what is public, therefore they don’t perceive this as an invasion of privacy. In the same sense, students could access the teacher’s/ instructor´s public information, however, some of the participants claim that they are not interested in seeing that information, while others claim that is interesting to know about some aspects of the teacher´s life, thereby generating more confidence and closeness.

In other cases, it was also highlighted that the use of Facebook in the classroom could generate a certain kind of distraction within the same platform. Which is why FB is recommended as a mediation strategy for independent work and for moments outside the classroom, as some students are entertained in other content, but at the same time they consider that the use of FB stimulates the process and find it much more entertaining than a common LMS platform in accordance with Wang et al. (2012). Further research on how using SMS can capitalize on increase social relationships in both blended and face-to-face instruction. As well as identifying tasks types that could be appropriate to immolate real-world communication using Facebook or other social media sites for that matter. Nevertheless, social media has made its way into the lives of learners; therefore, there should be constant research as to how to genuinely connect social media sites to the teaching and learning process.

Finally, students claim that using FB generates a close and more confident communication tool with the teacher. Mainly, because the teacher tended to respond faster on FB as compared to other LMS platforms and that response could be, private or public, dependent on the response. This alone, improves students´ focus and performance of a given task since long wait periods for feedback is not needed. This also corroborates how FB supports the learning process by improving the speed and confidence of communications between the student and teacher.

Akbari, E., Eghtesad, S., & Simons, R. (2012). Students’ attitudes towards the use of social networks for learning the English language. ICT for Language Learning.

Alexander, B. (2005). Web 2.0: A new wave of innovation for teaching and learning? Innovation, 41(2), 2005–2006.

Alhabash, S., & Ma, M. (2017). A Tale of Four Platforms: Motivations and Uses of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat Among College Students? Social Media and Society, 3(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2056305117691544

Alhazmi, A. K., Rahman, A. A., Computing, F., & Johor, S. (2013). Facebook in higher education: Students’ use and perceptions. Advances in Information Sciences and Service Sciences, 5(October), 32–41.

Arrington, M. (2005, September 8). 85% of college students use Facebook. TechCrunch, pp. 1–4. Retrieved from http://tcrn.ch/1TaoX6t

Bosch, T. E. (2009). Using online social networking for teaching and learning: Facebook use at the University of Cape Town. Journal for Communication Theory and Research, 35(2), 185–200. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02500160903250648

Boyd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00393.x

Caldevilla, D. (2010). Las redes sociales. Tipología, uso y consumo de las redes 2.0 en la sociedad digital actual. Documentación de Las Ciencias de La Información, 33, 45–68.

Capello, R., & Faggian, A. (2005). Collective learning and relational capital in local innovation processes. Regional Studies, 39(1), 75–87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320851

Cerdà, F. L. ., & Planas, N. C. . (2011). Facebook’s potential for collaborative e-learning [Posibilidades de la plataforma Facebook para el aprendizaje colaborativo en línea]. Revista de Universidad y Sociedad Del Conocimiento, 8, 197–210.

Chen, C. (1999). Information visualisation and virtual environments. London; New York: Springer.

Chiappe, A., Rozo, H., Menjívar, E., Corchuelo, M. A., & Alarcón, M. (2016). Educomunicación en entornos digitales: Mirada desde la comunicación no verbal. In Doctorado en educación: Temas y conceptos (1st ed., pp. 159–177). Chía: Universidad de La Sabana.

Cicourel, A. V. (1974). Cognitive sociology: Language and meaning in social interaction. New York, NY, US: Free Press.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

de Oliveira, I. (2009). Caminos de la educomunicación: utopías, confrontaciones, reconocimientos. Nómadas, (30), 194–207.

Dennen, V. P., & Burner, K. J. (2017). Identity, context collapse, and Facebook use in higher education: putting presence and privacy at odds. Distance Education, 38(2), 173–192. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2017.1322453

Eteokleous, N., Ktoridou, D., Stavrides, I., & Michaelidis, M. (2012). Facebook a social networking tool for educational purposes: developing special interest groups. ICICTE Proceedings, (2008), 363–375.

Gómez, M., Roses, S., & Farias, P. (2012). El uso académico de las redes sociales en universitarios. Comunicar. Revista Comunicar, 19(38), 131–138.

González P., M. (2013). Los estilos de enseñanza y aprendizaje como soporte de la actividad docente. Journal of Learning Styles, 6(11), 51–70.

Hill, J. R., & Hannafin, M. J. (2001). Teaching and learning in digital environments: The resurgence of resource-based learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 49(3), 37–52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02504914

Irwin, C., Ball, L., Desbrow, B., & Leveritt, M. (2012). Students’ perceptions of using Facebook as an interactive learning resource at university. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 28 (7), 28(7), 1221–1232. http://dx.doi.org/10.14742/ajet.798

Jahan, I., & Ahmed, S. M. Z. (2012). Students’ perceptions of academic use of social networking sites: a survey of university students in Bangladesh. Information Development, 28(3), 235–247. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0266666911433191

Junco, R. (2012). Too much face and not enough books: The relationship between multiple indices of Facebook use and academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(1), 187–198. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.08.026

Kaplún, M. (1998). Una pedagogía de la comunicación (1 ed.). Madrid: Ediciones De la Torre.

Kirkup, G., & Kirkwood, A. (2005). Information and communications technologies (ICT) in higher education teaching—a tale of gradualism rather than revolution. Learning, Media and Technology, 30(2), 185–199.

Labus, A., Despotović‐Zrakić, M., Radenković, B., Bogdanović, Z., & Radenković, M. (2015). Enhancing formal e‐learning with edutainment on social networks. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 31(6), 592–605.

Magogwe, J. M., Ntereke, B., & Phetlhe, K. R. (2015). Facebook and classroom group work: A trial study involving University of Botswana advanced oral presentation students. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(6), 1312–1323.

Manca, S., & Ranieri, M. (2013). Is it a tool suitable for learning? A critical review of the literature on Facebook as a technology‐enhanced learning environment. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29(6), 487–504.

Mazer, J. P., Murphy, R. E., & Simonds, C. J. (2007). I’ll see you on “facebook”: The effects of computer-mediated teacher self-disclosure on student motivation, affective learning, and classroom climate. Communication Education. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03634520601009710

Mazman, S. G., & Usluel, Y. K. (2010). Modeling educational usage of Facebook. Computers and Education, 55(2), 444–453. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.02.008

McDougald, J. S. (2013). The use of new technologies among in-service Colombian ELT teachers. Colombian Applied Linguistic Journal, 15(2), 247–264.

Moallem, M. (2015). The impact of synchronous and asynchronous communication tools on learner self-regulation, social presence, immediacy, intimacy and satisfaction in collaborative online learning. The Online Journal of Distance Education and E‐Learning, 3(3), 55.

Moore-Russo, D., Radosta, M., Martin, K., & Hamilton, S. (2017). Content in context: analyzing interactions in a graduate-level academic Facebook group. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0057-y

Pérez, T., Araiza, M. D. J., & Doerfer, C. (2013). Using Facebook for learning: A case study on the perception of students in higher education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 106, 3259–3267.

Pew Research Center (2019, April 10). Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Fact Tank. Retrieved from https://pewrsr.ch/2VxJuJ3

Picciano, A. G., Dziuban, C., & Graham, C. R. (2014). Blended Learning: Research perspectives, Volume 2. New York: Routledge.

Pons, X. (2010). La aportación a la psicología social del interaccionismo simbólico: una revisión histórica. Revista de Psicología y Psicopedagogía, 9(1), 23–42.

Puerta-Cortés, D. X., & Carbonell, X. (2013). Uso problemático de Internet en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios Colombianos. Avances En Psicologia Latinoamericana, 31(3), 620–631.

Richards, J. C., & Schmidt, R. W. (1983). Language and communication. London; New York: Longman.

Roblyer, M. D., McDaniel, M., Webb, M., Herman, J., & Witty, J. V. (2010). Findings on Facebook in higher education: A comparison of college faculty and student uses and perceptions of social networking sites. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(3), 134–140. http://dx.doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.03.002

Selwyn, N. (2007). Web 2.0 applications as alternative environments for informal learning - a critical review. Paper for CERI-KERIS International Expert Meeting on ICT and Educational Performance, 16–17. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/32/3/39458556.pdf

Smart, J. B., & Marshall, J. C. (2012). Interactions between classroom discourse, teacher questioning, and student cognitive engagement in middle school science. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 24(2), 249–267. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10972-012-9297-9

Statista. (2018). Global social media ranking 2018 | Statistic. Statista. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

Tello, E. (2007). Las tecnologías de la información y comunicaciones (TIC) y la brecha digital: su impacto en la sociedad de México. RUSC. Universities and Knowledge Society Journal, 4(2), 5.

Vidal, C. E., Martínez, J. G., Fortuño, M. L., & Cervera, M. G. (2011). Actitudes y expectativas del uso educativo de las redes sociales en los alumnos universitarios. RUSC, 8(1), 171–185.

Walther, J. B., & Jang, J. (2012). Communication processes in participatory websites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 18(1), 2–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2012.01592.x

Wang, Q., Woo, H. L., Quek, C. L., Yang, Y., & Liu, M. (2012). Using the Facebook group as a learning management system: An exploratory study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(3), 428–438. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2011.01195.x

Wankel, C. (2012). Educating educators with social media. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 26(3), E115–E116. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/dlo.2012.08126caa.012

1. Profesor e investigador del Centro de Tecnologías para la Academia de la Universidad de La Sabana. Doctorado en Ingeniería Informática. ronald.gutierrez@unisabana.edu.co

2. Director de Profesores e Investigacion. Departamento de Lenguas y Culturas Extranjeras. Universidad de La Sabana. jermaine.mcdougald1@unisabana.edu.co

3. Profesor e investigador del Centro de Tecnologías para la Academia de la Universidad de La Sabana. Doctorando en Educación. hugoroga@unisabana.edu.co

[Index]

revistaespacios.com

This work is under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial 4.0 International License