Vol. 40 (Number 32) Year 2019. Page 13

PRONCHEV, Gennadi B. 1; LYUBIMOV, Aleksei P. 2; PRONCHEVA, Nadezhda G. 3 & TRETIAKOVA, Irina V. 4

Received: 17/06/2019 • Approved: 04/09/2019 • Published 23/09/2019

5. Conclusion and Recommendations

ABSTRACT: The paper deals with studying labor migration in Russia within the context of motivation causes of the population's migration. Labor migration has been analyzed according to age-related, gender, and sociocultural characteristics of migrants. In Russia, the internal labor migration exceeds the external one in terms of volume. In the recent years, Russia's need of engaging foreign specialists has been decreasing. The work of state agencies in the field of migration policy of the Russian Federation has been analyzed. As the empirical base of the research, secondary data of the Russian and foreign researchers and statistical data of the state agencies were used. The materials of the research are of interest for the professionals dealing with labor migration problems. |

RESUMEN: El trabajo está dedicado a investigar la migración de la población laboral en Rusia en el contexto de las causas motivacionales de la migración. La migración laboral fue analizada según las características de edad, sexo, sociales y culturales de los migrantes. La migración laboral interna en Rusia por su alcance supera la migración externa. La necesidad de atraer a los especialistas extranjeros en Rusia sigue cayendo durante los últimos años. Fue analizado el trabajo de las autoridades estatales en el ámbito de la política migratoria de la Federación Rusa. En calidad de una base empírica de la investigación fueron utilizados los datos secundarios de los investigadores nacionales y extranjeros, así como los datos estadísticos de las autoridades estatales. Los materiales de la investigación son de interés para los especialistas que se dedican a los problemas de la migración laboral. |

In the recent decades, the globalization processes have promoted greater mobility of the population worldwide. According to the UN Department for economic and social affairs, over the years 2000 – 2017, the specific weight of migrants of the world's total population rose from 2,8% to 3,4% and currently amounts to some 258 million people (UN, 2017).

The dramatic events of the late 20th century led to the change of social and economic system in Russia (Lyubimov, 2013a; Lyubimov, 2014; Draskovic et al., 2017). This resulted in mass population movement flows featuring oppositely directed vectors. The prevailing trend is to move from economically weakened regions to regions and countries having a better provided for employment system, a higher wage level, and more comfortable conditions of life for migrants and resettlers. The Russian Federation currently ranks fourth in the world according to the quantity of migrants living in it (11,7 million people) and third in the list of countries – donors of migrants (10,6 million people) (UN, 2017).

At the same time, the migration processes and the demographic ones associated with them have a tremendous impact on the economic (Lyubimov, 2013b; Sushko et al., 2016b), political (Crawley & Skleparis, 2018; Mikhailov et al., 2018) and social sphere (Pronchev et al., 2018; Tretyakova, 2018b) and determine the citizens' lifestyle pattern (Sushko et al., 2016a).

In order to identify the place of labor migration in the motivations system of the present-day migrants, let the statistical data from the Social bulletin "Population in Russia: trends, problems, ways of solution" (Trubin et al., 2018) be analyzed. Table 1 presents the causes of inbound migration in Russia (% of the total). Alongside with the internal migration causes listed in the table, in 2016, there was the cause "coming back after temporary absence", the weight of this component amounting to 26,5% (Trubin et al., 2018).

Table 1

Causes of the Internal Migration in Russia

Year |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

Total of them: |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

reasons of personal or family nature |

61,1 |

58,9 |

59,0 |

50,1 |

47,4 |

45,8 |

45,5 |

43,8 |

34,8 |

due to studying |

8,1 |

8,4 |

8,5 |

11,5 |

12,7 |

14,1 |

14,8 |

16,9 |

8,9 |

due to work |

10,7 |

10,8 |

9,8 |

13,0 |

14,4 |

14,5 |

13,7 |

13,0 |

8,7 |

returning to the previous domicile |

11,5 |

11,2 |

9,5 |

6,5 |

4,9 |

4,3 |

3,6 |

3,4 |

2,7 |

due to aggravated interethnic relations |

0,03 |

0,03 |

0,03 |

0,04 |

0,03 |

0,02 |

0,02 |

0,03 |

0,02 |

due to aggravated crime situation |

0,02 |

0,02 |

0,02 |

0,03 |

0,02 |

0,02 |

0,02 |

0,02 |

0,02 |

environmental problems |

0,2 |

0,2 |

0,2 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

being unfit for the natural and climatic conditions |

0,3 |

0,2 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

other reasons |

7,1 |

9,2 |

12,0 |

16,0 |

17,3 |

17,1 |

17,7 |

17,7 |

14,3 |

no cause specified |

1,0 |

0,9 |

0,8 |

2,2 |

2,7 |

3,7 |

4,0 |

4,6 |

3,5 |

Source: Trubin et al., 2018, p. 28

Having analyzed Table 1, one can note that the internal migration reasons largely depend on personal and family circumstances, those associated with work and studies, returning to the previous domicile. Clearly, the latter is associated with the change in urbanistic attitudes as well as with the traditional lifestyle pattern, the so-called "urge to see one's home grounds", gradually losing its importance (Osipova et al., 2018a; Osipova et al., 2018b).

Moreover, it can be pointed out that in the internal migration of the period under analysis the specific weight of causes related to work and studying featured unstable dynamics in different time spans. Meanwhile, according to their volume, the two factors – "due to studying" and "due to work" – evidently have a prevailing role in the total of motives listed in the table. The internal migration contributes to redistribution of welfare and income levels, interregional and inter-settlement differences, somehow balancing the population's quality of life (Sushko et al., 2016b; Pronchev et al., 2018).

In Table 2, causes of the outbound migration are given (% of the total) (Trubin et al., 2018).

Table 2

Causes of the External Migration

Year |

Arriving |

Departing |

Migration gain |

|||

2008 |

2016 |

2008 |

2016 |

2008 |

2016 |

|

Total of them: |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

reasons of personal or family nature |

67,5 |

43,2 |

67,7 |

57,3 |

67,4 |

42,8 |

due to work |

9,4 |

18,0 |

6,3 |

8,4 |

9,9 |

18,3 |

other reasons |

8,8 |

11,7 |

7,5 |

19,8 |

9,0 |

11,4 |

due to studying |

1,4 |

7,1 |

1,9 |

2,7 |

1,3 |

7,3 |

due to aggravated interethnic relations |

1,4 |

6,1 |

0,1 |

0,1 |

1,6 |

6,3 |

returning to the previous domicile |

4,5 |

1,6 |

12,6 |

6,4 |

3,2 |

1,4 |

due to aggravated crime situation |

0,1 |

1,5 |

0,0 |

0,0 |

0,1 |

1,6 |

environmental problems |

0,2 |

0,2 |

0,1 |

0,2 |

0,3 |

0,2 |

being unfit for the natural and climatic conditions |

0,3 |

0,2 |

0,4 |

0,3 |

0,3 |

0,2 |

no cause specified |

6,4 |

10,4 |

3,3 |

4,9 |

6,9 |

10,6 |

Source: Trubin et al., 2018, p. 29

Causes of the external migration are similar to those of the internal migration in many respects, except the fact that the external migration already ranks second in importance within the context of generalizing term "personal and family reasons". That is, the internal labor migration exceeds the external one both in preferences and in volume. Admittedly, the main of these points is people's being oriented to labor, or as it goes in the table, "due to work'. Alongside with that, in the external migration, the percentage of movements associated either with work or studying is noted, too.

In its nature, labor migration has underlying economic grounds. Currently, "labor migration" is defined as "temporary migration in order to get employed and perform works (render services), within which seasonal labor migration is also singled out – a kind of labor migration of foreign citizens whose work depends in its nature on seasonal conditions and so is only performed during a part of the year" (Nikiforova & Tsindeliani, 2018).

According to the data of the Federal State Statistics Service, in 2016, over 4 million of Russians changed their permanent registration, with over 1,5 million citizens moving from one region to another (FSSS, 2016). In Russia, when looking for a better life and a higher wage, they move from towns to cities. These are regions having a favorable climate that is popular – the Central and Southern Russia. It should be noted that as a result of the internal migration processes certain difficulties are encountered both by the regions seeing the mass outward flow of its dwellers and the regions to which these dwellers arrive. Far not everyone of the migrants having arrived get easily adapted to social and economic realias of a big city. It is fairly often that migrants face the problem of searching for employment, accommodation and money. As a result, poverty and crime develop. The population's mass outflow can generate quite a lot of social and economic problems (Lyubimov, 2016).

The objective of this research is to study the current social and economic causes of labor migration in Russia.

The main tasks of the research are the following:

1. Analyzing the causes and structure of Russia's population migration.

2. Analyzing the age-related, gender, sociocultural features of Russia's internal and the external labor migrants.

3. Analyzing the work of the state agencies of the Russian Federation in the area of migration policy.

For completing the tasks associated with the analysis of interrelation of labor migration and the relevant factors, the following research methods were used: the comparative law, the systemic and structural, and the logical and semantic analysis.

The comparative law method was applied for finding out the shared and the different between the sources of law within the legal system of the RF and the system of international law according to the elements of migration processes.

The use of systemic and structural method has allowed finding out and analyzing the impact of social and economic processes on labor migration more extensively.

The logical and semantic analysis was applied for the search of correct definitions.

In the work, results and secondary data of Russian and foreign researchers, the official statistical data of the state agencies of Russia and international organizations were used.

In Russia, the need of engaging foreign professionals for conducting work activity has been going down in the latest years. The quantity of invitations for foreign professionals planned to be issued in 2019 will be provided for 144 583 people (GRF, 2018). This is 33 871 people less than in 2018 (178 454 people). In particular, the 5643 people reduction is planned for the quantity of foreigners – workers busy in mining, capital mining development, construction and installation, repair and construction operations, and the 8142 people one – for the quantity of foreigners working in other occupations of qualified workers at large and small industrial enterprises. Moreover, the need of engaging foreign workers in other professional and qualification groups can be shrunk so much as by 3018 people. The quantity of foreigners employed as operators, instrument control men, machine operators and assembly fitters of stationary equipment can be reduced by 4377 people, too, and that of drivers and mobile equipment drivers – by 3673 people (GRF, 2018).

It is evident that cutting the quota down to such levels will hardly deal with anything on the national scale, if it is taken into account that a significant part of the foreign workers are employed in agricultural works that do need a lot of manpower in fact (GRF, 2018).

It should be pointed out that alongside with cheap labor, the external migration to Russia entails quite a raft of economic, sociocultural and legal problems, too.

Among the negative economic consequences, there can be listed the fact that labor migrants export from the country a considerable part of the money earned, and no taxes are allocated to the budget when using illegal foreign migrants (Lyubimov, 2017). The positive aspect consists in there being no necessity for the employer to pay high wages when using illegal foreign migrants, which improves the competitiveness of the product manufactured.

Among the negative sociocultural consequences, there can be listed the fact that foreigners coming to Russia for work frequently have poor education and drastically different sociocultural traditions (Pronchev & Muravjov, 2013). Quite often, the migrants find it hard to integrate into the existing local community. Getting together in ethnic groups, they do not count on interaction with the country's population, and sometimes even place themselves in opposition to the society. Meanwhile, sociocultural exchange in the course of the indigenous population's possibly interacting with the migrants as well as interethnic families' emerging with the population growth prospect can be referred to the positive consequences.

Failing to find a job up to their personal demands or for enriching in an illegal way, some migrants lead a life of crime, which can be listed among the negative legal consequences. They join gangs and commit various wrongdoings (Tretyakova, 2018a; Petrov & Proncheva, 2018).

There is one more trend to be noted: far not all external migrants return to their motherland. It is very often the case that they leave for larger Russian centers (Tretyakova, 2018a).

For analyzing the dynamics of labor migration in Russia, let the analytical studies of E. M. Shcherbakova (2018) and her comments on the quantity of citizens performing labor activity within the Russian Federation and beyond it be used. It is noted in advance that that the estimates are given for the time span of up to the year 2018.

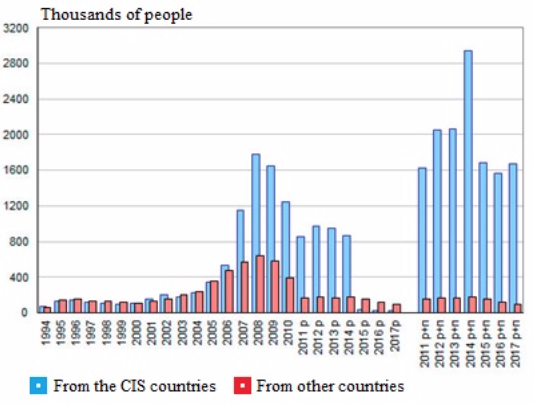

In 2011-2013, the share of foreign workers coming from the CIS countries went up to 84% of all those having a valid work permit. It made 83% in 2014, shrinking back to 18% in 2015 and to 17% in 2016-2017 (Shcherbakova, 2018).

It should be noted that the foreign workers who have obtained patents for performing labor activity are citizens of the CIS countries and have the visa-exempt access to Russia; alternatively, they are persons without citizenship who arrived to Russia without a visa drawn up.

Figure 1 shows the quantity of foreign citizens (in thousands of people) that were performing labor activity in Russia. As for the time span of 1994-2010, the data of the Federal Migration Service of Russia are presented, people without citizenship included. For the period of 2011-2012, the quantity of ones having a valid work permit as of the year end (p) is given, as well as the quantity of ones having a valid work permit as of the year end and having obtained patents for performing labor activity for individuals during the year (p+n). The time span of 2013-2017 represents the quantity of foreigners having a valid work permit or a valid patent as of the year end.

Figure 1

The Quantity of Foreign Citizens Performing Labor Activity in Russia

(Thousands of People)

Source: Shcherbakova, 2018, p. 6

The 2015 considerable reduction of the quantity of registered foreign citizens performing labor activity in Russia was largely associated with the economic downturn and reduction of the work pay level expressed in currency.

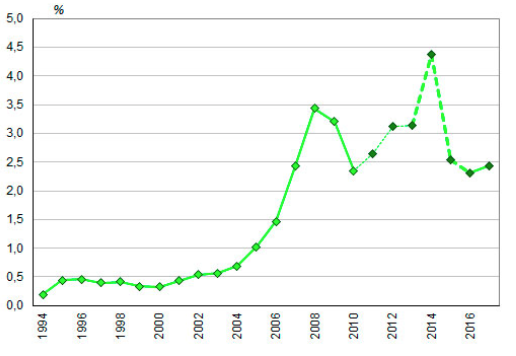

In the overall quantity of the employed in Russia's economy, the share of foreign workers went up from 0,3% in the years 1999-2000 to 3,4% in 2008. In 2009, it had a slight decrease back to 3,2%, and a more pronounced one, to 2,4%, in 2010 (Shcherbakova, 2018).

According to the 2011 data, the share of foreign workers having a valid work permit as of the end of the year, amounted to 1,5% of the total quantity of the economically employed, with the share of those obtaining their patents within 2011 making 1,1% more. The following years saw the percentage of foreign workers employed in Russia's economy grow gradually. In 2014, it went up to 4,4%, while the share of foreign workers having a valid work permit fell to 1,4% and that of patent holders grew up to 3% of the employed (Shcherbakova, 2018).

In 2015, the percentage of registered foreign workers employed in Russia's economy shrank down to 2,5%. The share of foreigners – valid work permit holders – went down to 0,3% of the economically employed while that of foreigners having a valid patent – to 2,3%. In 2016, the registered foreign manpower percentage continued to decrease – so low as to 2,3%, including 0,2% of foreigners having a valid work permit and 2,1% of those with a valid patent. By the end of 2017, the share of foreign workers employed in Russia's economy had a slight increase of up to 2,4%. Meanwhile, it was the percentage of foreigners having a valid work permit that went down a little (0,16% of the economically employed ones), with that of valid patent holders growing (2,28%) (Shcherbakova, 2018).

Figure 2 shows the percentage of foreign workers in Russia's economy (% of the total quantity of the employed ones as of the end of the year) in 1994 – 2017.

Figure 2

The Share of Foreign Workers (%) Performing Labor Activity in Russia in 1994 – 2017

Source: Shcherbakova, 2018, p. 6

Over 40% of foreign citizens performing labor activity on the basis of valid patents are people aged 18 to 29; next, some 30% – those aged 30 to 39, with 20% of the said being 40- to 49-year-old ones, and people aged 50 and older amounting to about 10%. The age-related breakdown of foreigners having a valid work permit is somewhat smoother. Among them, most of the people are 40-49 years old (32% as of the end of 2017) and 30-39 years old (29%), with the percentage of the youth aged 18-29 (19%) and of people aged 50 and older (20%, including 18% of the 50-59-year-old ones) being noticeably lower (Shcherbakova, 2018).

The main participants of the external labor migration are men (82% of workers having a valid work permit and 86% of ones having a valid patent as of the end of 2017). Men prevail in all age groups of foreign workers in Russia. The highest specific weight of women among workers having a valid patent was accounted for by the age group of 60-year-old and older ones (22%), the lowest – by the age group of 18-29-year-old women (9%). By contrast, among those having a valid work permit, the percentage of women was the highest in the 18-29-year-old age group (26%), and it was the lowest among women aged 50 and older (14%) (Shcherbakova, 2018). These are the gender distinctions that have remained up to the present day and are likely to persist for a long time.

The highly educated and qualified in their domains professionals are an individual group of migrants; regrettably, they frequently leave Russia. Having been well retrained abroad, a part of them return to work for the benefit of Russia. However, many of them after leaving Russia stay for the permanent residence to bolster the receiving countries' intellectual assets.

In the country having received them, highly qualified migrants create a tremendous added value for this country's national product with their talent and work. This is what G. I. Glushchenko and A. A. Vartanyan (2018) write about it: "For a convincing example, it suffices to look at the practice of the United States of America, where foreign students amount to about 5% of the total quantity of the US college students. However, they have contributed almost 33 billion dollars into the economy of the USA and created over 400000 jobs. … In 2016, all the six American Nobel prize winners both in economics and in other scientific areas were migrants".

The authors believe in Russia the problem of outflow of the highly qualified professionals from the country is not taken seriously enough. Basically, the process is not controlled in any way. O. D. Vorobyova and A. A. Grebenyuk (2016) point out: "The data of Rosstat for 2014 on emigration from Russia to Israel are 4 times lower than those of the Ministry of Aliyah and Integration of Israel, on emigration to the USA – 4,7 times lower than the data of the US Census Bureau, on emigration to Germany – 5 times lower than the data of the Federal Statistical Office of Germany etc. So, by the most conservative estimate, one needs to keep in mind a 3-4 times upward correction on the data of Rosstat in order to get a realistic idea about the scale of emigration from Russia".

According to the authors, it is solving this problem that needs special priority.

In conclusion, it can be noted that labor migration is the principal kind of migration in Russia. It depends both on the country's economic stability in general and on the quality of life of individual workers (political stability, environmental safety, comfortable living conditions).

Labor migration interacts with other kinds of migration and it can transform. For instance, a political refugee can become a labor migrant, temporary migration due to studies can become permanent, and so on.

Increased focus has to be put on migration policy on the part of the state, and a definite program of actions has to be available. The authors believe more attention should be paid to the Employment law and to more thoughtfully and actively solving the compatriots’ resettlement question. According to the experts, the current State program for the voluntary resettlement of compatriots (Decree, 2006) is not adhered to either in the scope or in deadlines due to budget expenditure optimization (Trubin et al., 2018).

This research was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (grant № 19-01-00089-a).

Crawley, H., & Skleparis, D. (2018). Refugees, migrants, neither, both: categorical fetishism and the politics of bounding in Europe’s ‘migration crisis’. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(1), 48–64.

Decree (2006). The decree of the President of the Russian Federation of June 22, 2006 No. 637 “About measures for rendering assistance to voluntary resettlement to the Russian Federation the compatriots living abroad”. Retrieved April 10, 2019 from: http://www.kremlin.ru/acts/bank/23937. (01.02.2019).

Draskovic, M., Milica, D., Mladen, I., & Chigisheva, O. (2017). Preference of institutional changes in social and economic development. Journal of International Studies, 10(2), 318-328.

FSSS (2016). Population size and migration of the Russian Federation in 2016. Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved February 10, 2019 from: http://www.gks.ru/bgd/regl/b17_107/Main.htm

Glushchenko, G.I., & Vartanyan, A.A. (2018). Socio-Economic Determinants of Highly-Skilled Migration. Voprosy Statistiki. 25(5), 27-41.

GRF (2018). Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 1494 of December 6, 2018 "On determining the need to attract foreign workers arriving in The Russian Federation on the basis of a visa, including priority professional qualification groups, and approval of quotas for 2019". The Government of the Russian Federation. Retrieved February 10, 2019 from: http://static.government.ru/media/files/

vc7Ho9q5utu5FctE74e1GryjCxUFAhCR.pdf

Lyubimov, A.P. (2013a). 20 years of the constitution of the Russian Federation. Representative Power – XXI Century, 7-8, 14-17.

Lyubimov, A.P. (2013b). Prospects of creation of Russian innovation clusters. Representative Power – XXI Century, 5-6, 14-19.

Lyubimov, A.P. (2014). The Era of change in Russia. Representative Power – XXI Century, 2-3, 1-2.

Lyubimov, A.P. (2016). The interests of the Russian inter-parliamentary cooperation with the EU. Representative Power – XXI Century, 1-2, 17-25.

Lyubimov, A.P. (2017). Political and Legal Framework of Electronic Democracy and Culture. Philosophical Sciences, 2, 79-88.

Mikhailov, A.P., Petrov, A.P., Pronchev, G.B., & Proncheva, O.G. (2018). Modeling a Decrease in Public Attention to a Past One-Time Political Event. Doklady Mathematics. 97(3), 247-249.

Nikiforova, E.A., & Tsindeliani, I.A. (2018). Immigration law: a textbook for students. In: I.A. Tsindeliani (Ed.). Moscow: Prospect.

Osipova, N.G., Elishev, S.O., & Pronchev, G.B. (2018a). Mass information media and propaganda mouthpiece as a tool for manipulating and social inequality factor among the young people. Astra Salvensis, 6, 541-550.

Osipova, N.G., Elishev, S.O., Pronchev, G.B., & Monakhov, D.N. (2018b). Social and political portrait of contemporary Russian student youth. Journal of Social Studies Education Research, 9(1), 28-59.

Petrov, A., & Proncheva, O. (2018). Modeling Propaganda Battle: Decision-Making, Homophily, and Echo Chambers. Communications in Computer and Information Science, 930, 197-209.

Pronchev, G.B., & Muravjov, V.I. (2013). About peculiarities of Internet technologies use for the civil society development in modern Russia. Representative Power – XXI Century, 7-8, 59-63.

Pronchev, G.B., Monakhov, D.N., Proncheva, N.G., & Mikhailov, A.P. (2018). Contemporary virtual social environments as a factor of social inequality emergence. Astra Salvensis, 6, 207-216.

Shcherbakova, E.M. (2018). Migration in Russia, preliminary results of 2017. In: Demoscope Weekly (763-764 pp.). Retrieved February 10, 2019 from: http://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2018/0763/barom01.php

Sushko, V.A., Pronchev, G.B., Proncheva, N.G., & Shisharina, E.V. (2016a). Emigration in Modern Russia. The Social Sciences, 11, 6436 -6439.

Sushko, V.A., Pronchev, G.B., Shisharina, E.V., & Zenkina, O.N. (2016b). Social and Economic Indices of Forming the Quality of Life. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(18), 10839-10849.

Tretyakova, I.V. (2018a). A sociological analysis of crime of foreigners and persons without citizenship in the Russian Federation. Education and Law, 9, 192-197.

Tretyakova, I.V. (2018b). On current trends in migration processes in Russia. Eurasian Law Journal, 9, 452-457.

Trubin, V., Nikolaeva, N., Myakisheva, S., & Khusainova, A. (2018). Migration of the population in Russia: trends, problems, solutions. Social Bulletin, 11. Retrieved February 10, 2019 from: http://ac.gov.ru/publications/4986

UN (2017). International migrant stock: The 2017 revision. Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations. Retrieved February 10, 2019 from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates17.shtml

Vorobyova, O.D., & Grebenyuk, A.A. (2016). Emigration from Russia at the end of the XX-th century. Analytical report. Moscow. Retrieved February 10, 2019 from: https://komitetgi.ru/upload/iblock/406/4066933fa72aa4d17d2012fe04ee33dd.docx

1. Department of Sociological Research Methodology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia. Contact e‑mail: pronchev@rambler.ru

2. Centre for International Law, Diplomatic Academy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia, Moscow, Russia. Contact e‑mail: gosduma624@yandex.ru

3. Keldysh Institute of Applied Mathematics, Russian Academy of Sciences; Department of Mathematical Modeling and Applied Mathematics, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Moscow, Russia. Contact e-mail: proncheva@yandex.ru

4. Department of Sociological Research Methodology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, Moscow, Russia. Contact e-mail: silvervessel@mail.ru