Vol. 40 (Number 31) Year 2019. Page 6

Vol. 40 (Number 31) Year 2019. Page 6

MOLCHANOVA, Irma Igorevna 1; SOKOLOVA, Nadezhda Vasilevna 2; GATINSKAYA, Nina Valentinovna 3; ZELENOVA, Olga Vasilevna 4 & CHEREPKO, Viktoria Vladimirovna 5

Received: 08/05/2019 • Approved: 03/09/2019 • Published 16/09/2019

3. Specifics of translating “False friends”

ABSTRACT: The article presents instructional techniques for teaching how to translate “false friends” and some training materials used in teaching foreign students who study the theory and practice of professionally oriented medical translation as part of the special course on translation fundamentals in English and French. The educational materials are designed to teach foreign students to correctly translate “false friends” in medical texts. The authors also show some sample training exercises to revitalise the educational material and speech tasks to introduce this material into speech. |

RESUMEN: El artículo presenta técnicas de instrucción para enseñar cómo traducir "falsos amigos" y algunos materiales de capacitación utilizados en la enseñanza de estudiantes extranjeros que estudian la teoría y la práctica de la traducción médica orientada profesionalmente como parte del curso especial sobre traducción en inglés y francés. Los materiales educativos están diseñados para enseñar a los estudiantes extranjeros a traducir correctamente "falsos amigos" en textos médicos. Los autores también muestran algunos ejercicios de entrenamiento de muestra para revitalizar el material educativo y las tareas del habla para introducir este material en el habla. |

The category of words referred to as “false friends” in the translation literature is of particular interest to researchers and teachers of translation. This interest is not casual, since the number of errors made when these words are translated is extremely high.

When doing a translation, it is important to distinguish genuinely international words, i.e. which are similar in spelling and pronunciation in different languages and coinciding in meaning from words that, despite of their external similarity, have different meanings. Words of the second category are especially “dangerous” for translators, as they often deceive them and are the cause of gross semantic errors. They are called “pseudo-international words” or “false friends” (or “false cognates”).

The term “false friends” (tracing from the French faux amis) was introduced by M. Koessler and J. Derocquigny in 1928 in their book “Les faux amis ou Les pièges du vocabulaire anglais” [1] for designating lexical units that are similar in spelling and pronunciation in the source and target languages but different in their semantic content.

The very “openness” of this term is attractive: it seems to remind of traps awaiting everyone who deals with different languages. It should be noted that, by “literal translation of false friends”, M. Kœssler and J. Derocquigny, meant translation only by the sound similarity of words in two languages. At present, the term “literal translation” is understood by some researchers much more broadly. In 1949, Ya.I. Retzker considered literalism as translation according to the external – graphic or phonetic – similarity and, in 1970, V.G. Gak already distinguishes between lexical, phraseological, grammatical and stylistic literalisms. (Varnikova 2007).

The problem of translating these lexical units from one language to another is not new: it was considered in the works of many authors, for example, V.V. Akulenko, T.S. Amiredzhibi, L.I. Borisova, V.N. Komissarov, V.L. Muravyov, D.V. Samoylov and others. Publications of English-Russian dictionaries of “false friends” are becoming more and more popular.

After analyzing the most popular works as a source, we used the work of V.V. Akulenko “About the false friends”: following this author, we define “false friends” as a pair of words in two languages, similar in spelling and/or pronunciation, often with a common origin, but different in meaning. For example, the English “angina” is “стенокардия”, “genial” is “добрый”, the French “materiel” is “оборудование”, “tablette” is “плитка”. Both English and French have the noun “magazine” that means “журнал”. At the same time, the French “journal” is the Russian “газета” or “дневник”. When comparing English and French with Russian, we can find a significant number of words that are spelt or pronounced similarly. These are mainly borrowings either by one language from another or – most often – by the three compared languages from a common source: as a rule, Latin or Greek. The number of borrowings from French in English (parliament, method, theory, organization, tissue, etc.) is quite significant. However, being borrowed by another language, a word often acquires new meanings, its semantic structure can completely change. Historically, “false friends” appear as a result of cross-language interaction or as random coincidences. (Akulenko 1969).

It should be noted that there is a considerable number of bilingual dictionaries dedicated to medical topics. However, dictionaries of “false friends” are much scarce. Besides that, little attention is given to medical topics in the dictionaries of “false friends”.

When dealing with “false friends”, a translator can be mislead by occurring false identifications, since interlingual analogisms (Gottlieb 1985) have some graphic (or phonetic), grammatical, and often semantic commonness. The cross-language interference (Kuznetsova 1990: 43–45) arising in this case is often caused by true or false semantic similarities of words.

Historically, “false friends” appear as a result of cross-language interaction; in a limited number of cases, they may be random coincidences; and, in closely related languages, they are based on related words that go back to common prototypes in the ancestor language. Their total number and the role of each of the possible sources in their appearance are different for each specific pair of languages, determined by the genetic and historical links between the languages.

As the researchers of this lexical category point out, the majority of “false friends” (with the exception of a few, the most obvious cases, related to homonymy) is “dangerous” specially for people who confidently and practically satisfactorily use the language, although they do not reach the level of adequate unmixed bilingualism and, therefore, are apt to make false identification of individual elements of foreign- and native-language systems.

The main sources of such errors are the similarity or apparent identity of the material of both languages in terms of pronunciation or function. In particular, in the field of lexis, it is “false friends” that not only especially often disorient translators but can sometimes mislead even professional philologists (e.g. lexicographers, professional translator or teachers of translation), which, due to the exclusivity of such facts, does not give any reason to consider these specialists as insufficiently knowing the language.

The authors share the opinion of L.I. Borisova (Borisova 2005) that the problem of “false friends” is of particular relevance when it comes to translations of special texts which abound with internationalisms. Especially important is the category of “false friends” for teaching medical translation, since medical vocabulary in English, French and Russian was formed under a strong influence of Latin and Greek.

In the literature on translation teaching methods, one can find both general approaches to teaching (Gavrilenko 2008) and the classification of errors (Buzadzhi 2009), techniques and exercises developed to avoid errors in translations (Latyshev 2005). The authors of the last work emphasize that it is necessary to draw students’ attention to the danger of “false friends”. V.L. Muravyov was one of the first to propose a system of exercises focused on this group of words using the French and Russian language material (Muravyov 1985). In addition, tests were developed to verify the formation of the basic and special components of the translator’s competence (Kobiakova 2014: 43 – 45) and an attempt was made to examine “false friends” when three non-closely related languages are in contact (Kurbanova 2012), but this was done not on the medical material which is of interest to the authors of the present study.

The “false friends” in English and French make up a large group of words, which pose rather a complex problem that becomes even more complicated as the differences in the meanings of compared words become thinner. When translating words of this category, it is necessary to refer to the dictionary, paying special attention to their ambiguity; it is not recommended to rely only on the similarity of their form or pronunciation.

An English or French word sometimes may have many different meanings; therefore, one should carefully search and select an appropriate equivalent. Translators should be attentive and make sure that the meaning of a given word also matches the style of a given text. Once “false friends” are found, they should be learnt.

Very useful for translators can be the English-Russian and Russian-English Dictionary of “False Friends” by V.V. Akulenko and others. The dictionary contains a detailed analysis of more than 1000 English words, in the vast majority with abstract meanings, that have Russian equivalents. Unfortunately, there is no similar large French-Russian and Russian-French dictionary of “false friends”. The existing dictionary by Muravyov V.L. has a limited vocabulary and is not focused on medicine.

We conducted an experiment at the Russian Language Department of the RUDN Medical Institute in groups attending a special course on the theory and practice of translation. The experiment involved four groups of foreign students trained in professional (medical) translation: two of them (experimental and control) studied French-Russian and Russian-French translation and the other two (also experimental and control) studied English-Russian and Russian English translation. Each group consisted of 15 students from different countries (Nigeria, Jamaica, South Africa, Ecuador, Israel, Morocco, Côte d’Ivoire, Benin, Algeria, Tunisia, etc.). The students of the two experimental groups trained in the special course on translation fundamentals in English and French studied the basics and difficulties of translating “false friends”. In these groups, we introduced training exercises on translations of international and pseudo-international words. Examples of these exercises are presented further in the article. We believe that, when performing these exercises, students should fix some of them graphically, that is, write them down. This can be formalized as homework or students’ individual work.

ILLNESS

Illness and sickness are generally used as synonyms for disease. However, this term is occasionally used to refer specifically to the patient's personal experience of his or her disease. In this model, it is possible for a person to be diseased without being ill, (to have an objectively definable, but asymptomatic, medical condition), and to be ill without being diseased (such as when a person perceives a normal experience as a medical condition, or medicalizes a non-disease situation in his or her life). Illness is often not due to infection but a collection of evolved responses, sickness behavior, by the body aids the clearing of infection. Such aspects of illness can include lethargy, depression, anorexia, sleepiness, hyperalgesia, and inability to concentrate.

Quand un laboratoire pharmaceutique découvre une nouvelle molécule (encore appelée médicament ou spécialité pharmaceutique), il dépose un brevet qui lui assure l’exclusivité de sa fabrication et de sa commercialisation pendant 20 ans. A l’expiration du brevet, la molécule tombe dans le domaine public, ce qui autorise d’autres laboratoires à en produire une copie conforme et à le vendre sous un no, commercial different de celui du médicament de référence. On parle alors de médicament générique. Génériques et médicaments de référence sont donc identiques par leur composition en principes actifs, ainsi que par leurs formes pharmaceutiques (ou galéniques).

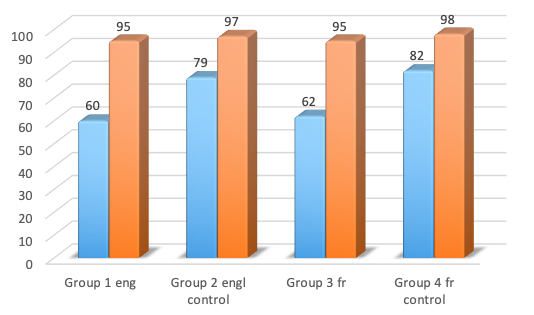

After the translation of the exercises, we tested all the four groups. All the students were offered medical texts containing international and pseudo-international words in English and French. Their task was to translate these texts without a dictionary. Observations during the experiment showed that the students did not hesitate to write translations of words and completed the task very quickly. However, after seeing the correct answers, the students were surprised. It was evident that many of them had not even expected how different the translations of words might be. Thus, after the first test on “false friends” was completed, the results in the experimental groups were low: 40% of words were misunderstood by the students. In the control groups, the results were high (79% and 82%, respectively). After we developed additional exercises for training “false friends”, the students were offered a test similar to the first one. As a result, as Diagram 1 shows, the number of errors was significantly reduced: the final test recorded 95% and 96% of correct answers, respectively (Diagram 1):

Diagram 1

Dynamics of correct answers of 4 groups

As the experiment showed, the knowledge of the specifics of the phenomenon of “false friends” helps to avoid “hidden pitfalls” when translating a text. For example, after checking student translations of medical texts from English and French into Russian, we found that the quality of translation increased by at least 35%.

After conducting the experiment and demonstrating the correct answers, we gave the students the following tips and recommendations:

1. One should not rely on one’s own intuition but always check the translation and the meaning of a word in the dictionary.

2. In English and French, words may have many different meanings; therefore, one should carefully search and find their correct equivalents.

3. One should be attentive and make sure that the meaning of a given word matches the style of a given text.

4. If “false friends” are found, they should be learnt once and forever; one can also keep a personal dictionary of “dangerous words”.

Summing up, it should be noted that the cross-language phenomenon being studied requires special attention from both linguists and translators, since ignorance of the lexical meanings of “false friends” can lead to a distortion of meanings in the process of communication and translation; therefore, it would be unreasonable to translate them, relying on one’s own intuition and on their native language.

Students’ familiarization with pseudo-international vocabulary and consistent work with this category of words in translations from English and French into Russian can significantly reduce the number of translation errors.

For teachers who teach Russian to foreign students, it is very important to have on-hand materials for practical applications.

Based on the above examples, we can conclude that medical translation requires of a translator a full understanding of a source text and long and hard work with dictionaries. In this area, it is unacceptable to deviate from the text content, arbitrarily add or remove words from the context, since correct translation is often critically important not only for effective treatment but also for the patient’s life.

1. Akulenko V.V. (1969). English-Russian and Russian-English Dictionary of “False Friends”. Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya, 355.

2. Borisova L.I. (2005). False Cognates. NVI-Thesaurus, 212.

3. Buzadzhi D.M., Gusev V.V., Lanchikov V.K., Psurtsev D.V. (2009). A new look at the classification of translation errors. All-Russian Center per. 120 - 121.

4. Gavrilenko N.N. (2008). Translation training in the field of professional communication. Monograph, 175 – 176.

5. Gottlieb G.M. (1985). The Dictionary of False friends Russian-German, German-Russian. Comp. K.G.M. Gotlib. 159 – 160.

6. Kobiakova N.L. (2014). Control and evaluation in foreign-language education as an essential component of the professional and personal development of the international-profile students. Continuous Pedagogical Education, 8, 43 – 45. Retrieved from http://www.apkpro.ru/294.html

7. Kuznetsova I.N. (1990). On the lexical interference in the same and in different languages. Moscow University Bulletin, 9 (1), 43 – 45.

8. Latyshev L.K., Semenov A.L. (2005). Translation: Theory, practice and teaching methods: a tutorial. 190 – 192.

9. Muravyov V.L. (1985). False cognates. Manual for teachers Fr. lang. V.L. Ants, 2, 45 – 47.

10. Varnikova A.P. (2007). Different meanings of similar words. Foreign Languages PLUS Journal, 2, 75.

1. Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), 117198, Russia, Moscow, Miklukho-Maklaya st., 6, e-mail: irmamolchanova@gmail.com

2. Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), 117198, Russia, Moscow, Miklukho-Maklaya st., 6, e-mail: martyn00@mail.ru

3. Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), 117198, Russia, Moscow, Miklukho-Maklaya st., 6, e-mail: gatinskaya@gmail.com

4. Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), 117198, Russia, Moscow, Miklukho-Maklaya st., 6, e-mail: iallo2210@mail.ru

5. Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), 117198, Russia, Moscow, Miklukho-Maklaya st., 6, e-mail: haul13@gmail.com