Vol. 40 (Number 21) Year 2019. Page 12

Vol. 40 (Number 21) Year 2019. Page 12

AMOR Almedina, María Isabel 1 & SERRANO Rodríguez, Rocío 2

Received: 19/03/2019 • Approved: 01/06/2019 • Published 24/06/2019

ABSTRACT: The use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and the ability to relate through the use of social networks have a significant influence on the development of Digital Competence. The objective of this study is to discover the amount of time pupils spend on activities related to digital media outside school hours, and to identify the skills acquired through these activities, in addition to their benefit as regards pupils’ learning and their increase in Digital Competence. |

RESUMEN: El uso de las Tecnologías de la Información y la Comunicación (TIC) y la habilidad para relacionarse a través de redes sociales influyen de forma significativa en el desarrollo de la Competencia Digital. El objetivo del presente estudio es conocer el tiempo que le dedica nuestro alumnado a actividades relacionadas con los medios digitales fuera del horario escolar, e identificar las habilidades adquiridas a través de estas actividades y su beneficio para el aprendizaje escolar y el incremento de la Competencia Digital. |

This work is focussed on pupils’ perceptions of their level of development as regards Digital Competence, i.e. their skills and abilities in the use and control of digital and analogical means of communication. The group that participated in this study, whose members were aged between 10 and 13, belong to a digital generation that maintains direct and continuous contact with the most common Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in present-day society (Delicado & Alves, 2010; Pereira, Pinto & Moura, 2015). For that reason, we shall also attempt to analyse the relevance that the use and handling of these media have in their daily lives, along with the contribution that they make to the acquisition and development of their Digital Competence. We are of the same opinion as Buckingham (2005) in that the way in which these media are used at and outside school is so different that a new type of digital distribution is emerging. The difference between what pupils learn in the classroom and what they learn elsewhere is, therefore, becoming increasingly more relevant (Pereira, Fillol & Moura, 2019), since the school is, on occasions, unable to provide or combine certain types of learning. According to Gee (2004, p.77), “people learn better when the learning forms part of highly motivated participation that they value”, in this case, digital means of communication and social networks.

This type of ‘informal’ education (Buckingham, 2005; Erstad & Sefton-Green, 2013; Scolari, 2018) plays an important role for pupils, since it begins with their interests and needs, in addition to the fact that it is shared with their peers and family members. All these agents have a great influence at that age and, therefore, tend to be fundamental sources of knowledge for them. The amount of time spent doing these activities is also a key factor for as regards attaining digital abilities and is, therefore, dealt with in this study, along with determinant variables, such as gender and attending extra-curricular computing classes.

Competence-based learning is characterized by its transversal nature, its dynamism and its integral nature, and the process of teaching/learning these competences should, therefore, be tackled in all knowledge areas and all those people of which the educational community is composed (De la Orden, 2011). These competences are not acquired at a particular moment and then remain unalterable, but rather imply a process of development through which individuals gradually acquire greater levels of performance in their use, thus giving them a certain dynamic nature. Tackling them also implies an integral education that will allow pupils to transfer the knowledge acquired throughout their lives. According to the DeSeCo (Definition and Selection of Competencies, 2005) Project, a competency supposes acquiring the capacity to respond to complex demands by means of various tasks adapted to each situation and context. It is thus possible to infer that learning is the set of skills, capacities, attitudes and values required to carry out efficient actions. It has three principal attributes: the integration of knowledge, the tackling of knowledge, skills and attitudes, which make it possible to act in an appropriate manner when confronted with new situations according to each context (Tiana Ferrer, 2011).

According to the DeSeCo (Definition and Selection of Competencies, 2005) Project, a competency supposes acquiring the capacity to respond to complex demands by means of various tasks adapted to each situation and context. It is thus possible to infer that learning is the set of skills, capacities, attitudes and values required to carry out efficient actions. It has three principal attributes: the integration of knowledge, the tackling of knowledge, skills and attitudes, which make it possible to act in an appropriate manner when confronted with new situations according to each context (Tiana Ferrer, 2011).

In a report written for UNESCO (1996) denominated as ‘Education Encloses a Treasure’, Jacques Delors defined four fundamental pillars on which the education of future European citizens should rest. These pillars suppose educational foundations into which knowledge such as learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together and learning to be are integrated:

Education is, therefore, the integration of abilities and skills that goes beyond the acquisition of knowledge and supposes determining what one considers to be fundamental, in order to attain quality training that will serve to orientate us in order to create pedagogic policies (Pérez Esteve & Zayas, 2007).

According to the Eurydice study (2002), for a competence to be considered key and/or essential it must have the following three highly important qualities:

The European Commission (2013, 2011) recommends a series of key competencies that its member states must ensure are acquired by all, and which are the following:

The Spanish Organic Laws for Education (LOE, 2006; LOMCE, 2013) later stated that the curriculum is a set of objectives, basic competences, contents and pedagogic methods and evaluation criteria of each of the areas of teaching, and established the following basic competences for the Spanish education system:

The Royal decrees concerning minimum learning specify these competencies and define their development at each educative stage in the Royal Decree on Primary Education

1513/2006 and the Order of the 17th March, 2015, showing the specific contribution made by each competency to the different areas or subjects on the curriculum.

Improving Digital Competence as regards educating pupils favoured the inclusion of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in schools. The ICT domain is fundamental in present-day society, and education and the role of the teacher are very important as regards the acquisition of this ability (Bas, Kubiatko & Murat, 2016). The provision of resources with which to facilitate access to technologies has, therefore, been one of the crucial elements in relation to avoiding inequality among pupils. There are, nevertheless, still differences in the way in which pupils develop these competences that concern individual, socio-economic and family-related factors (Moreno, Guzmán & García, 2017).

Digital Competence supposes having the skill to handle and use ITC and is measured by employing indicators that show the perception that individuals themselves have about their abilities to use ICT with regard to surfing the Internet: seeking, finding and organising information, creating databases; handling a computer: creating graphics, drawings and working with images; communication and social relations: sending an email, contacting other people, etc. (Zhong, 2011; Van Braak & Kavadias, 2005; OECD, 2010). One of those most frequently used in empirical analyses is the pupils’ confidence when handling technologies, i.e. their own perceptions of their efficiency as regards these aspects. The most recent lines of research are focussing on the way in which young people use devices (Selwyn, 2004), in order to discover whether they are capable of obtaining greater benefits from them, and the differences among them in relation to their abilities to handle these technologies (Hatlevik & Christophersen, 2013). Both boys and girls generally state that their level is higher than that which they actually have, and what is more, there are variables such as gender. For example, boys automatically assume that they are more competent in these skills. Moreover, the pupils’ socio-economic level may facilitate their access to technologies, and the type of education centre at which they are studying may have an influence, because there may be differences among the infrastructures and educational resources that they have (Kuhlmeier & Hemker, 2007).

Although this piece of data may obviously represent a good approximation to Digital Competence, existing evidence shows that pupils state that they have a higher level than is actually the case and that there is a relationship among certain characteristics related to them, such as gender and the tendency to exaggerate certain competencies, i.e. males stating that they have a better digital competency than they really have (Gee, (2004; Kuhlmeier & Hemker, 2007; Pereira, Fillol, & Moura, 2019). However, the study by Aesaert & Braak (2015) concluded that girls have better technical abilities than boys.

The level of classmates’ competences may also be a predictive variable as regards pupils’ digital competence. It would appear to be logical that a pupil’s digital competency will improve when his or her classmates show that they have better skills with new technologies. In all cases, the causal relationship between the pupil’s competence and the average competence of his or her classmates probably moves in both directions in a reciprocal manner. The solution is to use a variable that is truly exogenous, i.e. that is more closely related to the characteristics of the pupils or their families than to their behaviour (Pereira, Fillol & Moura, 2019). We consider that access to technology outside the education centre may also be an important external variable with which to measure these abilities, since better access to ICT has a positive influence on a pupil’s acquisition of digital competence.

The method employed in this research is based on a quantitative methodology of a descriptive and comparative nature.

To discover the level of development of Digital Competence in Primary School pupils in their sixth year.

To analyse the relationship between the level of development of Digital Competence and the amount of time that the pupil spends doing activities with the computer outside the classroom.

To verify whether there are differences in the development of Digital Competence according to gender.

The present study was carried out with the participation of a total of 343 Primary School pupils in their sixth year, of which 48.4% were boys and 51.6% were girls. Of this total, 212 (61.8%) were at state schools and 131 (38.2%) were at private schools. All were studying in the city of Córdoba (Spain), and were aged between 10 and 13 (M=11.13; D.T=.382).

We designed an ad hoc questionnaire in order evaluate abilities and skills, consisting of the

development and acquisition of the key competences in the sixth year of Primary Education. The questionnaire was created after reading specialised literature on this subject, while the validation was carried out by experts in teaching at that stage in education. After consulting detailed up-to-date scientific material, we obtained a set of fundamental perceptions that related the items of the instrument with the research objectives.

The questionnaire reflects the different variables being studied and each item was defined operationally. In order to validate the instrument (calculate its reliability), we used Cronbach’s Alpha, and obtained a total of .96 with a confidence level of 95%. As a general criterion, George and Mallery (2003, p.231) suggest that, when evaluating research, an Alpha Coefficient of >.9 is excellent.

The questionnaire was formed of a total of 82 items related to the development and acquisition of basic competences in accordance with the Order of March 17th, 2015, which consequently led to the development of the curriculum corresponding to The Primary Education Stage in Andalusia. In the present work, we present only the results obtained for the 17 items related to the development of Digital Competence. The items obtained a reliability of .88. In order for reliability to be accepted, the value obtained for the reliability of the exploratory research must be greater than or equal to .6, while the confirmatory studies must be between .7 and .8 (Huh, Delorme & Reid, 2006). The domain of each of these competencies was evaluated using a Likert-type scale of ‘1’ (little) to ‘5’ (excellent).

We first carried out a descriptive analysis in order to discover the pupils’ perceptions of their level of Digital Competence and how much time they dedicate to activities related to using the computer, computing, social networks, etc.

We then used the Cronbach’s Alpha to carry out an analysis of the global reliability and individual variances of each item if this is eliminated. We subsequently carried out an Exploratory Factorial Analysis (EFA) in order to explore the set of latent variables or common factors that would explain the responses to the items on the questionnaire, along with a Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA) in order to specify the number of factors and the factorial weights of each one of them. The data obtained for the aforementioned EFA

and CFA were also analysed using the Kaiser Meyer-Olkin (KMO) tests and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, in addition to the Eigenvalues and the common aspects. We also carried out a visual observation of the sedimentation graphics.

We next carried out a Student t test for independent samples with the objective of discovering whether attending extra-curricular computing classes contributed to the acquisition of a greater capacity as regards Digital Competence and also whether there were any differences between boys and girls.

We finally carried out an ANOVA test in order to discover whether the amount of time that the pupils dedicated to the pursuit of computer-related activities allowed them to improve their Digital Competence. The data were codified, analysed and interpreted using the SPSS Statistics statistical software, version 20.

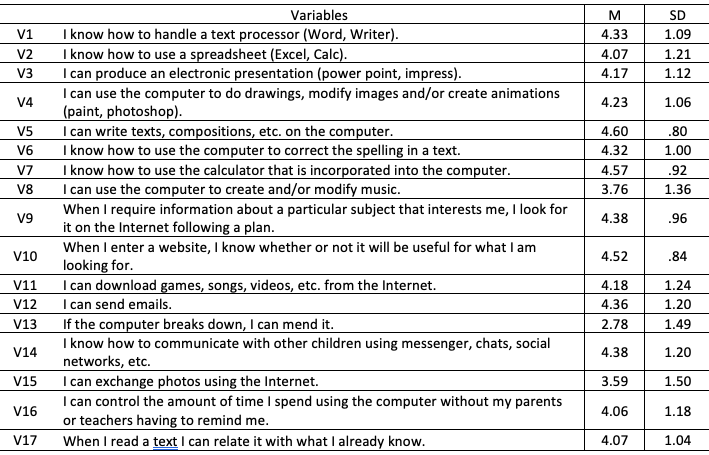

Table 1 shows the means (M) obtained for each one of the items of which the questionnaire was formed, and it will be noted that the results are fairly homogeneous. One exception is item (V13), for which the pupils showed a lack of competence as regards solving problems related to the functioning of a computer and which obtained a fairly low value (2.78). However, the item that obtained the highest value of 4.60 was (V5), “I can write texts, compositions, etc. on the computer”, followed by item (V7), “I know how to use the calculator that is incorporated into the computer”, which obtained a value of 4.57.

Table 1

Items of which the scale is composed

We subsequently carried out a descriptive analysis of the variable that shows how long the pupils spend doing computer-related activities: studying, doing work and homework, playing videogames or talking to their friends using social networks, chats, etc. The results obtained show (Table 2) that the majority of the participants (N=182) spend between 0 and 1 hours (58.3%), followed by those who spend between 1 and 2 hours (N=63) with a frequency of 20.2%; 10.9% (N=34) spend between 2 and 3 hours and 6.1% spend between 3 and 4 hours (N=19), while those who spend more than 4 hours suppose 4.5% of the sample (N=14).

Table 2

Amount of time pupils spend

doing computer-related activities

Hours/week |

N |

% |

0-1 |

182 |

58.3 |

1-2 |

63 |

20.2 |

2-3 |

34 |

10.9 |

3-4 |

19 |

6.1 |

+4 |

14 |

4.5 |

A value close to 1 was obtained for the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test for the sample scale (KMO=.901). Moreover, the Bartlett test of spericity had a level of significance of less than .05, (gl=136; Sig.=.000), signifying that the viability of carrying out a factorial analysis was also confirmed.

The Exploratory Factorial Analysis (EFA) revealed the existence of 3 factors, which the Confirmatory Factorial Analysis (CFA) confirmed, in addition to specifying the factorial weights in each of them. These 3 factors are related to the following dimensions:

In the first dimension (D1) it is possible to group those pupils who feel very capable when using computers for academic purposes: seeking and selecting information from the Internet, writing texts using specific processors (Word, write, etc.). The second dimension (D2) describes pupils who perceive themselves to be very competent as regards using computers for a more creative purpose: they like to manipulate and exchange photographs, create images, music, etc. and are capable of repairing the computer if it breaks down; the third dimension (D3) refers to those pupils who principally use the computer to relate to and communicate with others using emails and social networks.

Table 3 (below) shows the calculations regarding the reliability of each of these dimensions.

Table 3

Cronbach’s Alpha for each of the factors

Factors |

Nº elements |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

M |

D1 |

9 |

.83 |

4.3 |

D2 |

5 |

.73 |

3.7 |

D3 |

3 |

.71 |

4.3 |

Total |

17 |

|

|

As will be noted in Table 3, the values obtained show a fairly acceptable internal consistence among the items in each dimension. The highest vale is in D1, with .83, followed by D2 (.73) and D3 (.71). With regard to the means (M) of the different groupings of the items on the scale, note that (Graphic 1) D1 and D3 obtained identical values (4.3).

Graphic 1

Pupils’ levels of ability in each dimension on the scale

In order to verify whether extra-curricular computing classes contributed towards the pupils acquiring a better level of Digital Competence, we used the Student t test, which provided results showing that the differences in the means between the two groups (pupils who attended extra-curricular computing classes and those who did not) and the results obtained by using the aforementioned analyses illustrate that those pupils who attended extra-curricular computing classes obtained significantly higher scores as regards all the abilities with the exception of one, specifically item (V13), “If the computer breaks down, I can mend it”, (t343=2.133,p<.05).

However, when we carried out the Student t test in order to verify whether there were any differences between boys and girls as regards their development of the abilities grouped in this dimension, the results obtained showed that there were significant differences in the first dimension D1 (t343=-3.528, p<.05), since the boys felt highly capable of using a computer for academic purposes and less capable of using it for creative purposes, the abilities in the second dimension, D2 (t343=-.684, p<.05), and of using it to relate to and communicate with others using social networks (the third dimension - (D3) (t343=-1.146, p<.05).

The results of the ANOVA test carried out to discover whether the time spent doing activities related to computers contributed towards the pupils acquiring greater abilities in Digital Competence show that there are significant differences between D1 and D3. In order to contrast these results, we used Snedecor’s F. In our case, D1 is worth 2.441 and has a p-value of (sig.) = .04>.05; D2 is worth 2.212 and has a p-value of (sig) = .06>.05, while D3 is worth 3.947 and has a p-value of (sig.) = .00<.05.

To finish, and in order to discover for which groups in the first dimension (D1) and the third dimension (D3) these differences were statistically significant, we carried out post hoc tests, the results of which showed that there were no statistically significant differences in D1. However, in D3 there are differences between the group that spends 0-1 hours using the computer and that which spends 2-3 hours using the computer (p=.03).

In this study, as has occurred in previous studies (Kennedy, Krause, Judd, Churchward & Gray, 2006; Lenhart, Madden & Hitlin, 2005; Livingstone & Bober, 2004 and Oliver & Goerke, 2007), we have been able to verify that more than 75% of pupils in Primary Education have a good level of abilities in the handling and use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) when carrying out tasks related to the academic and social spheres. They feel very competent in activities related to communication and seeking information, which confirms their condition as ‘digital natives’.

We should stress the importance of the relationship between the pupils’ families’ socio-

economic level and their access to ICT, along with the role played by the school environment in that competence (Kuhlmeier & Hemker, 2007). On the one hand we have confirmed Moreno, Guzmán and García’s (2017) findings that the access to technological resources outside the education centre, which is partly a consequence of families’ socio-economic level, is positively related to pupils’ Digital Competence.

The results of the study consist of a descriptive analysis in which the percentages in the three dimensions analysed are evaluated and which provide valuable information to be taken into consideration in these conclusions. Of the three dimensions analysed, that in which the pupils consider themselves to be least competent is that concerning activities of a graphic or creative nature. Moreover, there are differences between boys and girls, since the boys obtained lower values, unlike that which occurred in the study by Kuhlmeier and Hemker (2007), who showed that boys tend to overvalue the level of their competences. Our results are, nevertheless, similar to those obtained by Aesaert and Braak (2015).

The amount of time that the pupils spend doing computer-related activities, by which we mean tasks related to communication, information and social relationships, is also important (Van Deursen & Van Diepen, 2013). However, the pupils’ use of these means is considered to be ‘rest time’ and rarely are they recognised as a source of learning; they are normally associated with a source of entertainment and leisure, even by the pupils themselves. They identify school with a place of work, effort and learning and the world of computer media as a space for enjoyment and pleasure. Nevertheless, we were able to verify that there is no positive correlation between the amount of time spent using the computer and the development of digital competence, since those pupils who spend between 2 and 3 hours on extra-curricular digital activities school are those who obtained the highest vales as regards the development of these skills.

To conclude, it would be advisable to extend the study carried out in Spain as far afield as possible in order to verify the validity of these results in other countries, which would be possible because the subject in question is important for education in general, beyond our geographical frontiers.

Aaen, J. & Dalsgaard, C. (2016). Student Facebook groups as a third space: Between social life and schoolwork. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(1), 160-186. Recovered from https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2015.1111241

Aesaert, K. & Braak, J. (2015). Gender and socioeconomic related differences in performance based ICT competences. Computer & Education, 84, 8-25.

Bas, G., Kubiatko, M. & Murat, A. (2016). Teacher’s perceptions towards ICT in teaching-learning process: Scale validity and reliability study. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 176-185. Recovered from https://doi. org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.022

Buckingham, D. (2005). Schooling the digital generation. Popular culture, new media and the future of education. London: Institute of Education.

Consejo de la Unión europea (2010). Council conclusions on increasing the level of basic skills in the context of European cooperation on schools for the 21st century. Recovered from http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cms_data/docs/pressdata/en/educ/117853.pdf.

De la orden, A. (2011). Reflexiones en torno a las competencias como objeto de evalua- ción en el ámbito educativo. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 13(2), 1-21. Recovered from http://redie.uabc.mx/vol13no2/contenido-delaorden2.html.

Delicado, A. & Alves, N. A. (2010). Children, Internet cultures and online social networks. In S. Octobre, & R. Sirota (Dir.), Actes du colloque enfance et cultures: Regards des sciences humaines et sociales (pp. 1-12). Recovered from https://bit.ly/2PbvKkt

Delors, J. (1996) La educación encierra un tesoro. Informe a la UNESCO de la Comisión Internacional sobre la Educación para el Siglo XXI. Santillana Ediciones, UNESCO, 1996.

Erstad, O. & Sefton-Green, J. (2013). Digital disconect? The ‘digital learner’ and the school. In O. Erstad, & J. Sefton-Green (Eds.), Identity, community, and learning lives in the digital age (pp. 87-104). New York: Cambridge University Press. Recovered from https://doi.org/10.3726/978-1-4539-1019-1

European Commission (2013). Survey of Schools: ICT in Education. Benchmarking Access Use and Attitudes to Technology in Europe’s Schools. http://dx.doi.org/10.2759/94499

European Commission (2011). Teaching Reading in Europe: Contexts, Policies and Practices. Brussels. Recovered from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED541704

EURYDICE (2002). Las competencias clave. Un concepto en expansión dentro de la educación obligatoria. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Recovered from http://formacion.intef.es/pluginfile.php/110561/mod_resource/content/1/Competencias%20clave%20de%20eurydice.pdf

Gee, J.P. (2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. New York & London: Routledge.

George, D. & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update (4a ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Hatlevik, O.E. & Christophersen, K. (2013). Digital Competence at the Beginning of Upper Secondary School: Identifying Factors Explaining Digital Inclusion. Computers & Education, 63, 240-247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.015

Huh, J., DeLorme, D. E. & Reid, L. N. (2006). Perceived third-person effects and consumer attitudes on prevetting and banning DTC advertising. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 40(1), 90-116. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2006.00047.x

Kennedy, G., Krause, K., Judd, T., Churchward, A. & Gray, K. (2006). First year students’ experiences with technology: are they really digital natives? Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne.

Kuhlmeier, H. & HemKer, B. (2007). The Impact of Computer Use at Home on Students Internet Skills. Computers & Education, 49, 460-480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2005.10.004

Lenhart, A., Madden, M. & Hitlin, P. (2005). Teens and technology: Youth are leading the transition to a fully wired and mobile nation. Washington DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project.

Ley Orgánica 8/2013, de 9 de diciembre, para la mejora de la calidad educativa. Boletín Oficial del Estado nº 295 de 10 de diciembre de 2013.

Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Educación. Boletín Oficial del Estado de 4 de mayo de 2006.

Livingstone, S. & Bober, M. (2004). Taking up online opportunities? Children’s use of the Internet for education, communication and participation. ELearning, 1, 3, 395–419.

Moreno, C., Guzman, F. & García, E. (2017). Primary education students´reading and writing habits: an analysis in and out of school. Porta Linguarum, 117-137.

OECD (2010). Are the New Millennium Learners Making the Grade? Technology use and educational performance in PISA. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264076044-en

OCDE (2005) Definition and Selection of Competencies (DeSeCo). Recovered from http://www.oecd.org/education/skills-beyond-school/definitionandselectionofcompetenciesdeseco.htm

Oliver, B. & Goerke, V. (2007). Australian undergraduates’ use and ownership of emerging technologies: implications and opportunities for creating engaging learning experiences for the next generation. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 23(2), 171–186. Recovered from http://www.ascilite.org.au/ajet/ajet23/oliver.html

Orden de 17 de marzo de 2015, por la que se desarrolla el currículo correspondiente a la Educación Primaria en Andalucía. Boletín Oficial de la Junta de Andalucía nº 60 de 27 de marzo de 2015.

Pereira, S., Fillol, J. & Moura, P. (2019). El aprendizaje de los jóvenes con medios digitales fuera de la escuela: De lo informal a lo formal. Comunicar, 58 (XXVII), 41-50.

Pereira, S., Pinto, M. & Moura, P. (2015). Níveis de literacia mediática: Estudo exploratório com jovens do 12.o ano. Braga: CECS. Recovered from https://bit.ly/2o1ML4r

Pérez Esteve, P. & Zayas, F. (2007) La competencia en comunicación lingüística. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Ramírez, A., Corpas, C., Amor, M. I. y Serrano, R. (2014). ¿De qué soy capaz? Autoevaluación de las competencias básicas. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 16(3), 33-53. Recovered from http://redie.uabc.mx/vol16no3/contenido-ramirezcorpas.html

Real Decreto 1513/2006, de 7 de diciembre, por el que se establecen las enseñanzas mínimas de la Educación Primaria. Boletín Oficial del Estado de 8 de diciembre de 2006.

Scolari, C.A. (2018). Informal learning strategies. In C.A. Scolari (Ed.). Teens, media and collaborative cultures – Exploiting teens’ transmedia skills in the classroom (pp. 78-85). Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Recovered from https://bit.ly/2vMXPGX

Selwyn, N. (2004). Reconsidering Political and Popular Understandings of the Digital Divide. New Media and Society, 6(3), 341-362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444804042519

Tiana Ferrer, A. (2011). Análisis de las competencias básicas como núcleo curricular en la educación obligatoria española. Revista Bordón, 63(1), 63-75.

Van Braak, J. & Kavadias, D. (2005). The Influence of Social-demographic Determinants on Secondary School Children’s Computer Use, Experience, Beliefs and Competence». Technology. Pedagogy and Education, 14 (1), 43-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759390500200192

Van Deursen, A. & Van Diepen, S. (2013). Information and Strategic Internet Skills of Secondary Students: A Performance Test. Computers & Education, 63, 218-226.

Zhong, Z. (2011). From Access to Usage: The Divide of Self-reported Digital Skills among Adolescents. Computers & Education, 56, 736-746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2010.10.016

1. Doctor in Educational Psychology. University of Cordoba (Spain). m.amor@uco.es

2. Doctor in Educational Psychology. University of Cordoba (Spain). Corresponding author: rocio.serrano@uco.es