Vol. 40 (Number 16) Year 2019. Page 8

CHERNOVA V.Yu. 1; ANDRONOVA I.V. 2; DEGTEREVA E.A. 3; ZOBOV A.M. 4 & STAROSTIN V.S. 5

Received: 31/01/2019 • Approved: 24/04/2019 • Published 13/05/2019

ABSTRACT: Mutual trade between member states is one of the core indicators of integration processes. Using the case of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), the paper analyses the dynamics of interregional trade and outlines the factors exerting a significant influence on the indicators. The article assesses the integration of the EAEU member states on the basis of intra-regional trade significance index. The study demonstrates that the deepening integration within the EAEU and the growing mutual trade served as an impetus for economic recovery of the member states after the 2008/2009 and 2014/2015 crises. |

RESUMEN: El comercio bilateral entre países es un de los indicadores principales de los procesos de integración. En este artículo se analiza la dinámica del comercio intrarregional de la Unión Económica Euroasiática (UEEA), como ejemplo, se demuestran los factores que impactan significativamente los indicadores. En este artículo se evalúa la integración de los países participantes de la UEEA en términos del indicador de importancia del comercio intrarregional. El estudio demuestra que la profundización de la integración de los países de la UEEA y el crecimiento del comercio bilateral sirvieron como impulso para recuperación de las economías de los países de la unión de integración después de las crisis de los años 2008-2009 y 2014-2015. |

Today’s global economic order is rather contradictory. On the one hand, globalization transforms the global economy into a single holistic mechanism; on the other hand, the crisis shocks of the last decade result in the creation of new regional associations and the strengthening of the existing ones. The growing economic power of several nations, such as China and Russia, has launched a tough competition between key global players for sales markets and limited resources (Andronova 2016), which further aggravates contradictions between countries and regions instead of trying to resolve them (Babanov and Zunde 2016).

The fact that clear and uniform operational guidelines for implementing sustainable development policy on the global scale are impossible to establish proves the necessity to look at the regional level as the key one in terms of development and introduction of modern sustainable development models (Mishenin et al. 2018). In the context of forming Russia’s effective economy in the new geopolitical reality, it is of growing importance to find mutually beneficial ways to initiate foreign contacts. One of the solutions to this problem is to deepen integration within the EAEU, whose main objective is to create favorable conditions for developing the member countries’ economies and enhancing their competitiveness. The main provisions of the Treaty on the EAEU are aimed at encouraging positive macroeconomic and political effects. In reality, due to a number of reasons the effects of integration may not always be manifested to the full extent.

Despite the potentially positive impact of the latest impulses (the trade and economic cooperation between the EAEU and the PRC, the creation of a free trade zone with the Republic of Iran) on restoring economic growth of the EAEU nations, the rates of the intra-union integration are rather slow. For example, mutual trade growth rates of the EAEU member countries in January–October 2018 were significantly lower than those in 2017: Armenia – 122.6% in 2018 and 145.0% in 2017, Belarus – 101.8% and 119.0%, Kazakhstan – 111,1% and 133,9%, Kyrgyzstan – 101,2% and 121,1%, Russia – 114,9% and 129,4% respectively. At the same time, in all the states participating in the EAEU, the growth rate of trade with third countries exceeds the growth rate of trade within the EAEU. The growth rate of foreign trade with third countries in January–October 2018 in comparison with the same period of the previous year has increased in Belarus – by 121.0%, Kazakhstan – by 127.2%, Kyrgyzstan – by 133.7% and Russia – by 120.9%. At that, the foreign trade growth in Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia was mainly due to exports.

Geopolitical interests are the major driving force for Russia when building partnering relationships with the CIS and the EAEU countries. However, new trends in the development of the global economy require nations to be more active in participating in integration unions. The purpose of the study, therefore, is to evaluate the integration level of the EAEU member states and identify the influence of macroeconomic and political factors.

Integration of the member countries within the EAEU has been growing in popularity in scientific literature. The ideas about regional integration being able to counteract adverse economic conditions and belonging to the anti-crisis strategy were under discussion at an early stage of research (Libman and Vinokurov 2012; Glazyev, Chyshkin and Tkachuk 2013; Libman and Vinokurov 2014; Vinokurov 2014), which was confirmed in the economic recovery of the participating countries after the financial crisis in 2014 (the Eurasian Development Bank 2018). At the same time, macroeconomic and political factors exert an immediate impact on the intensity of integration processes. Alpysbaeva and Shuneev (2018) distinguish between two groups of factors: external (a changing trend in the global economy development, positive and negative changes in its growth rate, dynamics of forecast prices for oil and metals) and internal (demographic factors, a reducing share of working age population, implementation of import substitution policy, consumer reorientation to competitive products of the EAEU member countries, barriers, exemptions and restrictions in mutual trade).

According to Kondratyeva (2018), Western sanctions have significantly influenced the integration process: they improved the potential of import substitution but reduced other expected benefits from the integration. The regime of sanctions has also sowed some sort of a discord between the EAEU nations and Russia (Irishev and Kovalev 2014). According to Libman (2015), the political crisis, on the one hand, caused a stir among the EAEU countries about Russia’s tremendous influence, but, on the other hand, made Russia more oriented towards compromising with the EAEU countries.

The contradictory nature of today’s global order and severe competition among the key world players for markets and limited resources, in particular, also influence the integration between the EAEU states (Andronova 2016). The global policy becoming more and more aggressive allows us to talk about the development of new protectionism (Bremmer and Kupchan 2018), which became one of the substantial risks of the world trade in 2018. The EAEU nations, therefore, need to upgrade their foreign policies and build them with due regard to this global trend (Sarkisyan 2018).

Eurasia Group analysts argue that new protectionism is characterized by the fact that countries now apply protective measures not only in relation to traditional industries (such as agriculture, metal production, car industry, chemical and arms industry), but also use protectionist measures in the digital economy and innovation-intensive industries with a view to protecting intellectual property and related technologies as the most important components of national competitiveness (Bremmer and Kupchan 2018). According to Travkina (2015), export-based economic growth consists of (1) direct growth in exports, (2) growth in managed exports, (3) development of feedback relationships and (4) maintaining a ratio balance. Development of ideas on dynamic security has led to a defined “floating” balance, when the market due to its movement inertia crosses an equilibrium point, from a condition of relative deficit to an account surplus of supply and demand, and vice versa (Kuzmin 2015, 2016).

The distinguishing feature of new protectionism is that its measures are often aimed at political opponents, which is especially obvious in foreign investment regulation (Bremmer and Kupchan 2018). Moreover, now the USA-initiated global protectionism has reached such a level, at which it has turned into one of the major risks to global economic growth. In addition to the direct effect on the dynamics of the world economy, it can exercise a significant impact on the development of regional integration unions boosting their attractiveness as an alternative to cooperation within global associations and forming a network (Lisovolik and Uzan 2018). A spatial network is a new normality of innovation systems that demonstrate a heterogeneous set of interorganizational relationships and the constant dissemination of information, knowledge, practices and other resources of actors involved in regional integration (Mikhaylov 2018). Network structures form a specific cluster with single conditions for performing economic activity (Kantemirova et al., 2018).

Regional integration is among the processes of integrated transformation and is characterized by intensification of intergovernmental relationships. The strengthening or weakening interrelations between economies determine if there is, or not, a positive integration dynamics. To assess the regional integration dynamics and its effects, a specialized system of indicators is applied (the EDB Centre for Integration Studies 2014). Most of the current indicators systems that are focused on the assessment of cross-border market integration use mutual trade dynamics indicators (including total trade) and intra-regional trade intensity indices.

The share of intra-regional trade in total foreign trade is a traditional indicator for assessing cross-country integration. The central drawback of the method is the fact that the number of countries in the region under consideration influences the indicator’s value. In addition, as the total share of the countries in the integration union in GDP grows, the share of intra-regional trade increases as well, regardless of the fact whether there is a real progress in integration or not. Nevertheless, its time-related dynamics, ceteris paribus, indicates positive effects in trade.

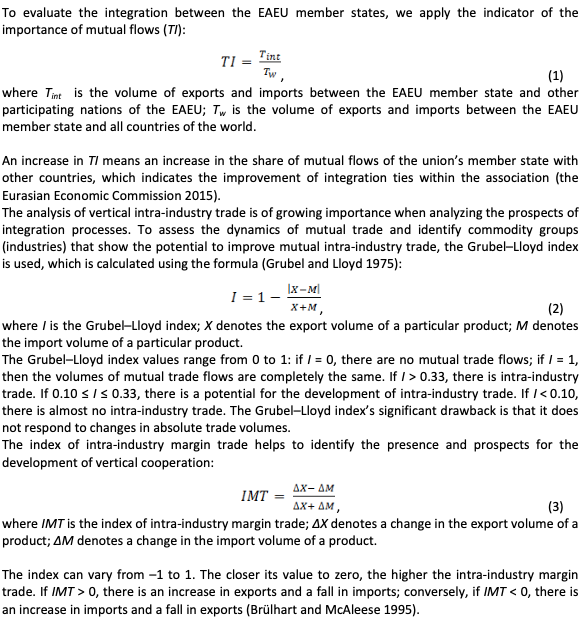

Since 2015, the EAEU member states have been experiencing a gradual recovery of economic growth after the 2014/2015 crisis. In 2017, there were positive shifts in GDP volume index of in all the union’s economies. The Republic of Belarus, the Republic of Armenia and Kazakhstan displayed the highest rates of economic growth (Fig. 1).

Figure 1

GDP volume indices of

the EAEU nations in 2017

Source: Compiled by the author using

(the Eurasian Economic Commission, 2018b).

In 2017, GDP volume in Russia was 1.8%. In the first half of 2018, the Republic of Belarus and Armenia demonstrated high growth rates; in Russia and Kazakhstan, the volume index slightly increased. At the same time, only Armenia and Belarus succeeded in achieving the maximum growth rate since 2013.

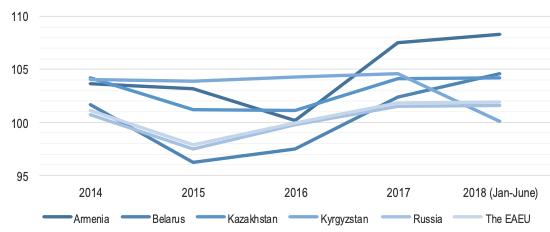

During this period, the key source of economic growth in the EAEU countries was manufacturing industries. However, in some countries the industrial development was due to extraction of mineral resources. Except for Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, which demonstrated a decline and a significant decline in 2018 respectively, the manufacturing industries of all the other member countries grew considerably, with the strongest increase in the Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2

Manufacturing volume indices in

the EAEU member nations in 2017

Source: Compiled by the author using

(the Eurasian Economic Commission, 2018b).

The import substitution policy being implemented does not produce a significant increase in agriculture: the agriculture volume index has been decreasing in all the countries since 2016, with the exception of the Republic of Armenia, where in the first half of 2018 there was observed an increase of almost 6% (Fig. 3).

Figure 3

Agriculture volume indices in the

EAEU member nations in 2017

Source: Compiled by the author using

(the Eurasian Economic Commission, 2018b).

The recovery of domestic demand, which stemmed from the growing final consumption expenditure, accelerated economic growth in the EAEU countries. This is associated with an increase in real wage in all the EAEU member states, except for Kazakhstan, where earned income has been falling over the past three years. The maximum increase in earned income was established in Belarus (6.2%), which increased real disposable income of the population of Belarus by 1.5%. The details of labor migration exert an immediate effect on earned income redistribution. At the same time, there is an inverse relationship between GDP per capita, consumer price index, minimum wage, unemployment rate and population migration rate (Todorov, Kalinina and Rybakova 2018).

The EAEU countries also witnessed a rise in fixed capital investment. In 2017, the fixed capital investment rate in Russia was 4.4%, in Kazakhstan – 5.5% and in Kyrgyzstan – 7.1%. The share of foreign capital in the EAEU member states’ fixed capital is still limited. For example, the share of foreign investment in the financing of fixed capital is below 1%.

The growth of exports and imports of the EAEU countries in foreign markets in nominal and real terms is attributed to a number of factors: a more favorable price situation in foreign markets; a rise in economic activity and demand within the EAEU and its trading partners; increasing production in export-oriented industries; an increase in consumer and investment activity, which, according to the EEC experts, is associated with the implementation of pent-up demand during the economic recession and high inflation (the Eurasian Economic Commission, 2018a).

Mutual trade within the EAEU is one of the key indicators of integration processes within the union. In 2015 and early 2016, the member states experienced a decline in the intraregional trade, which was due to falling commodity prices and a slowdown in the world economy and domestic demand. As for Russia, economic sanctions resulted in a decline in its export volumes. The sharpest decrease in trade turnover within the EAEU occurred in the first half of 2015 with a fall in the indicator by 26.1%. However, as early as in 2016, physical trade volume grew by 0.4%, with its reduction in monetary terms by 6.7%. In 2017, in all the EAEU participating countries, with the exception of Armenia, there was a marked increase in both exports and imports. At that, in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia, the export growth rate exceeded the import growth rate.

A decline in trade volume was also typical of both domestic trade within the EAEU and trade with third countries. Nevertheless, the decline in trade with third countries in 2015–2016 was more dramatic than that in mutual trade. As compared to 2015, the volume of foreign trade of the EAEU nations with third countries in 2016 reduced by 12%, or 69.6 billion US dollars. At that, exports fell by 17.5% (65.4 billion US dollars) and import – by 2% (4.2 billion US dollars). At the end of 2017, exports exceeded the volume of all mutual trade of the EAEU member countries by 3.6 times, and mutual exports – by 7.1 times.

The financial crisis in Russia – the country with the strongest economy among all the participating states and having the largest share in trade turnover since export and import operations of the EAEU states are virtually completely concentrated on Russia’s market – produced a significant fall in mutual trade in 2014–2016. Russia is a principal trade partner for the EAEU nations, as evidenced by the intraregional trade significance index (Table 1).

Table 1

Intraregional trade significance index for the

EAEU member states (according to 2017 data)

Region |

Armenia |

Belarus |

Kazakhstan |

Kyrgyzstan |

Russia |

EAEU |

29.76 |

52.56 |

22.77 |

38.43 |

9.02 |

Armenia |

0.14 |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.33 |

|

Belarus |

1.02 |

1.04 |

2.92 |

5.68 |

|

Kazakhstan |

0.24 |

2.24 |

17.00 |

3.16 |

|

Kyrgyzstan |

0.04 |

0.43 |

1.25 |

0.30 |

|

Russia |

29.11 |

51.91 |

21.35 |

28.00 |

Source: Calculated by the author using

(the Eurasian Economic Commission, 2018c)

A decline in trade with third countries amid the economic downfall resulted in the fact that the significance of the domestic trade within the EAEU started growing. Belarus is the most active participant of intra-union trade; its share in export and import accounts for about 45% and 57% respectively. At that, 95% of Belarus exports and approximately 99.5% of the country’s imports are accrued to Russia. Kyrgyzstan is another EAEU member state with close trade ties with the other participants of the association. Unlike exports from Armenia, Belarus and Kazakhstan that are primarily focused on the Russian market, Kyrgyzstan, due to its geographical position, is equally concentrated on both the markets of Russia and Kazakhstan.

In the export structure of Armenia within the EAEU, Russia accounts for roughly 97% of the trade volume. Mutual trade between Kazakhstan and the other EAEU countries is developing less dynamically. Exports of Kazakhstan are mainly focused on third countries; however, intra-union trade is also quite important for the country (Table 2). For Russia, intra-union trade is of secondary importance. An increase in the mutual trade significance index, therefore, is attributed to a falling trade with third countries.

Table 2

The dynamics of the mutual trade significance index within the EAEU

|

Mutual trade significance index |

Factors in the index’s changes |

|||

Export to the EAEU |

Import from the EAEU |

Export to third countries |

Import from third countries |

||

Armenia |

|||||

2017 |

29.76 |

2.1 |

3.0 |

–1.2 |

–2.8 |

2016 |

28.43 |

1.9 |

0.6 |

0.4 |

3.0 |

2015 |

22.42 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Belarus |

|||||

2017 |

52.56 |

2.2 |

2.9 |

–2.7 |

–2.2 |

2016 |

52.41 |

0 |

–1.8 |

3.6 |

1.1 |

2015 |

49.62 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Kazakhstan |

|||||

2017 |

22.77 |

1.6 |

3.0 |

–3.7 |

–0.4 |

2016 |

22.13 |

–1.5 |

–2.6 |

2.9 |

1.6 |

2015 |

21.74 |

|

|

|

|

Kyrgyzstan |

|||||

2017 |

38.43 |

1.4 |

0.6 |

–0.4 |

–1.6 |

2016 |

37.92 |

0.9 |

–4.4 |

0.1 |

–2.7 |

2015 |

44.13 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Russia |

|||||

2017 |

9.02 |

1.4 |

0.7 |

–1.3 |

–0.7 |

2016 |

8.93 |

–0.5 |

–0.1 |

1.2 |

0.1 |

2015 |

8.21 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Source: Calculated by the author using (the Eurasian Economic Commission, 2018c).

The reasons behind the dynamics vary significantly and the main of them are the following:

- the price factor due to the share of energy resources which prevails in the EAEU international trade;

- a slowdown in the global economy growth rate: a 2.44% increase in global GDP in 2016 compared to 2.73% in 2015, which is the lowest rate indicated after the 2008–2009 financial crisis;

- maintaining and extending the existing sanctions regime and reciprocal measures of Russia that is the key partner in the trade within the EAEU;

- the negative dynamics of GDP and industrial production of the two largest EAEU member states – the Republic of Belarus and the Russian Federation;

- depreciation of the national currencies against the US dollar.

The analysis of the intra-industry trade between Russia and the EAEU member countries by disaggregated commodity groups of the food industry showed that there was a vertical integration in a number of the commodity groups (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Index of the marginal intra-industry trade in the food industry in Russia and the EAEU countries

Source: Calculated by the author using (the Eurasian Economic Commission, 2018c).

In the food industry, almost all the commodity groups of the intra-industry trade of Russia with other EAEU nations exhibit a development potential (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Grubel-Lloyd index in food trade between Russia and the EAEU countries

Source: Calculated by the author using (the Eurasian Economic Commission, 2018c).

Despite the import substitution policy that Russia implements in the food industry and agricultural complex, the country’s integration level with the EAEU members remains quite low. Nevertheless, almost all commodity groups have the potential to deepen integration.

There are various external and internal problems impeding the integration between the EAEU participating countries at large and in the sphere of agriculture, in particular. According to the survey of independent experts (the Eurasian Development Bank 2009), the challenges for integration (in descending order) are the factors as follows: domestic policy priorities, foreign policy priorities, the quality of public governance and the level of the participating countries’ economic development.

Alpysbaeva and Shuneev (2018) identify the following crucial external and internal factors that underlie the development of integration processes in the EAEU: a changing direction of the global economy development, a slowdown and an acceleration of its growth rates; dynamics of forecast prices for oil and metals; the intensity of the mining industries’ development; demographic factors and a shrinking share of economically active population and the share of working age population; import substitution policy and reorientation of consumers to competitive products of the EAEU member countries, as evidenced by the intense saturation of the national markets with goods of the EAEU countries; keeping eliminating barriers, exemptions and restrictions in mutual trade.

A number of authors (see, for example, (Naumov 2015)) highlight that trade barriers serve as an obstacle to integration within the EAEU and can have a significant impact on the deepening of integration processes. The emergence of such obstacles is due to both the differences in the customs and tariff policy followed at the time of the formation of the Union and the application of non-tariff measures. Such measures introduced indicate that the policy is inconsistent and the countries pursue their protectionist interests.

Kondratyeva (2018) stresses that the Western sanctions regime enhanced the potential of import substitution but reduced other benefits expected from the integration. The regime also caused a discord within the EAEU, since Belarus and Kazakhstan were not supportive of the Russian countersanctions that ran afoul of their national interests (Irishev and Kovalev 2014).

The importance of the consistent policy for the EAEU integration is proved by the documents published by the Eurasian Economic Commission. The main macroeconomic objectives (the Eurasian Economic Commission 2018d) consider the measures to overcome negative consequences of external shocks, such as shifts in prices for energy resources, and to mitigate the effects of external risks. The central focus is put on improving the macroeconomic situation, stimulating investment in fixed assets, increasing value added and developing non-resource exports (the Eurasian Economic Commission 2018a). At the same time, one cannot but note the impact of political factors on integration processes. On the one hand, the political crisis is believed to cause concern of the EAEU member states over Russia’s dominant influence and their dependence on the larger and stronger economy, which will increase their disposition to adopt protectionist policy. On the other hand, the political crisis improves Russia’s readiness to compromise. However, since the outcome of the political crisis is uncertain, it is impossible to make any accurate predictions about the EAEU (Libman 2015).

While macroeconomic and political factors affect integration and disintegration processes, so the opposite is true – integration exerts influence on macroeconomic indicators of the countries. The recovery of the growth rates of the EAEU economies after the 2014 crisis confirms the hypothesis about the ability of regional integration to resist the unfavorable economic conditions and be part of an anti-crisis strategy (see, for example, (Libman and Vinokurov 2012; Glazyev, Chushkin and Tkachuk 2013; Libman and Vinokurov 2014; Vinokurov 2014). According to the EDB experts, the deepening integration of the EAEU countries and increasing mutual trade provided an impetus for the recovery of the union’s economies after the crisis (the Eurasian Development Bank 2018).

The study on real and institutional convergence in the EAEU nations stresses that different levels of economic development of the member states do not inhibit the evolution of the entire integration association. At the same time, economic integration can encourage greater institutional convergence within the EAEU. As with most other integration associations, within the EAEU, growth rates of the member countries are converging, but not their levels (Pelipas 2017).

This paper has highlighted that integration within the EAEU member states and the expansion of mutual trade stimulated the recovery of the union’s economies after the crisis. The results obtained show that agriculture and agribusiness exhibit a significant potential and provide vast opportunities for deepening integration between Russia and the EAEU nations. Due to the fact that the domestic market is limited and there is a need for boosting exports of agricultural products, Russia, like any other EAEU member country, is interested in expanding cooperation. In reality, however, the opposite processes also happen to be. The impact of macroeconomic and political factors on integration led to the fact that integration within the EAEU was no longer so beneficial for the participating countries. It is extremely important, therefore, to propose appropriate measures to overcome the negative effects of external shocks. As stated by Sarkisyan (2018), for the EAEU member countries, the intensification of competition between key global players and the new global protectionism make it necessary to coordinate foreign policy with this global trend in mind.

The publication was prepared with the support of the “RUDN University Program 5-100” within the framework of the project “Improvement of marketing tools to support and expand the import of consumer goods in the real sector of the Russian economy”.

Alpysbaeva, S. and S. Shuneev. (2018). Modelling of Long-Term Macroeconomic Effects of Integration of Kazakhstan in the EEU. Trade Policy, no. 1/13: 11-22.

Andronova, I. (2016). Eurasian Economic Union: Opportunities and Barriers to Regional and Global Leadership. International Organizations Research Journal, no. 2: 7-23.

Babanov, A. and V.Zunde. (2016). Regional Economic Integration in the Global Economy of the 21st Century. State and Municipal Management. Scholar Notes, no. 2: 132-138.

Bremmer, I. and C. Kupchan. (2018). Top Risks 2018. Risk 7: Protectionism 2.0. https://www.eurasiagroup.net/live-post/risk-7-protectionism-2.

Brülhart, M. and D. McAleese. (1995). Intra-Industry Trade and Industrial Adjustment: The Irish Experience. The Economic and Social Review, no. 2: 107-129.

Glazyev, S., V. Chushkin and S. Tkachuk. (2013). The European Union and the Eurasian Economic Union: Similarities and Differences in the Processes of Integration. Moscow: Vikor Media.

Grubel, H. and P.J. Lloyd. (1975). Intra-Industry Trade: The Theory and Measurement of International Trade with Differentiated Product. London: Macmillan.

Irishev, B. and M. Kovalev. (2014). The Future of the EAEU: A Complex Search for Balance and Growth. Journal of the Association of Belarusian Banks, no. 31-32: 746-747. http://elib.bsu.by/bitstream/123456789/106026/1/N_31_32.pdf.

Kantemirova, M.A., Dzakoev, Z.L., Alikova, Z.R., Chedgemov, S.R. and Soskieva, Z.V. (2018). Percolation approach to simulation of a sustainable network economy structure. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 5(3): 502-513. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2018.5.3(7)

Kondratyeva, N. (2018). The EAEU Through the Eyes of Experts. http://www.e-cis.info/foto/news/20185.pdf.

Kuzmin, E.A. (2015). Food Security Modelling. Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia 12(Spl. Edn. 2): 773-781.

Kuzmin, E.A. (2016). Sustainable Food Security: Floating Balance of Markets. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues 6(1): 37-44.

Libman, A. (2015). Ukrainian Crisis, Economic Crisis in Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/63861/1/MPRA_paper_63861.pdf.

Libman, A. and E. Vinokurov. (2012). Holding-Together Regionalism: Twenty Years of Post-Soviet Integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Pp. 11-37. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137271136

Libman, A. and E. Vinokurov. (2014). Do Economic Crises Impede or Advance Regional Economic Integration in the Post-Soviet Space? Post-Communist Economies 26, no. 3: 341-358. https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2014.937094

Lisovolik, Y. and M. Uzan. (2018). New Global Governance: Towards a More Sustainable System. A Report of the Valdai International Discussion Club, no. 88: 1-18. https://eabr.org/analytics/research-articles/yaroslav-lisovolik-mark-uzan-novoe-globalnoe-upravlenie-na-puti-k-bolee-ustoychivoy-sisteme-doklad-m/.

Mikhaylov, A. (2018). Socio-Spatial Dynamics, Networks and Modelling of Regional Milieu. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 5, no. 4: 1020-1030. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2018.5.4(22).

Mishenin, Y., I. Koblianska, V. Medvid and Y. Maistrenko. (2018). Sustainable Regional Development Policy Formation: Role of Industrial Ecology and Logistics. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 6, no. 1: 329-341. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2018.6.1(20).

Naumov, A. (2015). Analysis of Mutual Trade and Integration Barriers of the Eurasian Economic Union. Concept, no. 09. http://e-koncept.ru/2015/15317.htm.

Pelipas, I. (2017). Real, Nominal and Institutional Convergence in the EAEU Member Countries. Working Paper WP/17/03 of IPM Research Center.

Sarkisyan, T. (2018). The Deep Integration of the EAEU Economies Should Be Improved in the Light of the Global Trend for Protectionism. http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/nae/news/Pages/12-09-2018-2.aspx.

The EDB Centre for Integration Studies. (2014). Quantitative Analysis of the Economic Integration of the European Union and the Eurasian Economic Union: Methodological approaches. St. Petersburg: The EDB Centre for Integration Studies.

The Eurasian Development Bank (2009). Eurasian Integration Indicators System. The Eurasian Development Bank, Almaty.

The Eurasian Development Bank (2018). Foreign Trade Operations of the EAEU Member Countries: Trends and Potential Points of Growth. https://eabr.org/upload/iblock/5a4/Spets_doklad_2018.pdf.

The Eurasian Economic Commission (2015). Methodical Approaches to the Analysis of Integration Processes in the Customs Union and the Common Economic Space. http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_makroec_pol/investigations/Documents/integr_meths.pdf.

The Eurasian Economic Commission (2018a). On The Results and Prospects of Socio-Economic Development of the EAEU Member States and Measures Taken by the EAEU Member States in the Field of Macroeconomic Policy. http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_makroec_pol/economyViewes/Pages/annual_report.aspx.

The Eurasian Economic Commission (2018b). Socio-Economic Statistics. www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_stat/econstat/Pages/dynamic.aspx.

The Eurasian Economic Commission (2018c). Foreign and Mutual Trade Statistics. http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_stat/tradestat/tables/Pages/default.aspx

The Eurasian Economic Commission (2018d). The Main Guidelines of the Macroeconomic Policy of the EAEU Member States for 2018-2019. http://www.eurasiancommission.org/ru/act/integr_i_makroec/dep_makroec_pol/investigations/Documents/%D0%9E%D1%80%D0%B8%D0%B5%

D0%BD%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%80%D1%8B%20%D0%92%D0%95%D0%AD%D0%A1_14052018_11.pdf

Todorov, G., A. Kalinina and A. Rybakova. (2018). Impact of Labour Migration on Entrepreneurship Ecosystem: Case of Eurasian Economic Union. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 5, no. 4: 992-1007. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2018.5.4(20).

Travkina, I. (2015). Export and GDP Growth in Lithuania: Short-run or Middle-run Causality? Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 3, no. 1: 74-84. https://doi.org/10.9770/jesi.2015.2.4(7).

Vinokurov, E. (2014). A Megadeal in the Crisis. Why integration of the European Union and the Eurasian Economic Union should be Discussed Now. Russia in Global Politics, no. 5. http://www.globalaffairs.ru/number/Megasdelka-na-fonekrizisa-17113.

1. Department of Marketing, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Russian Federation; Department of Advertising and Public Relations, State University of Management, Russian Federation. Email: veronika.urievna@mail.ru

2. Department of International economic relations, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Russian Federation. Email: аiv1207@mail.ru

3. Department of Marketing, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Russian Federation. Email: degsed@mail.ru

4. Department of Marketing, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), Russian Federation. Email: a.zobov@mail.ru

5. Institute of Marketing, State University of Management, Russian Federation. Email: vs.starostin@guu.ru