Vol. 40 (Number 7) Year 2019. Page 13

SERRANO-LÓPEZ, Ana L. 1; ASTUDILLO-DURÁN, Silvana V. 2; MUÑOZ-FERNÁNDEZ, Guzmán A. 3; GONZÁLEZ SANTA CRUZ, Francisco 4

Received: 28/10/2018 • Approved: 30/01/2019 • Published 04/03/2019

4. Research results and discussion

ABSTRACT: In the field of tourism, job satisfaction has a direct impact on the quality of the service provided and, as a consequence, on the company’s image. This paper reviews some explanatory variables regarding job satisfaction in the hotel sector and makes an empirical application centered on field work undertaken in the hotels of the city of Cuenca (Ecuador). The current analysis is based on descriptive techniques and contrast of hypothesis, seeking to verify if the employees’ gender, age, marital status, or educational level affect their job satisfaction. |

RESUMEN: La satisfacción laboral de los empleados en el ámbito del turismo, repercute directamente en la calidad de la prestación del servicio y, por extensión, en la imagen de la empresa. Este trabajo analiza algunas variables explicativas sobre la satisfacción laboral en el sector hotelero y hace una aplicación empírica centrada en un trabajo de campo realizado en los hoteles de la ciudad de Cuenca (Ecuador). El análisis realizado está basado en técnicas descriptivas y de contraste de hipótesis, buscando verificar si los factores sociodemográficos afectan en satisfacción laboral. |

The management of organizations has evolved historically according to the changes that have taken place worldwide in social, political or cultural fields, among others (Werther & Davis, 2008), although these changes have occurred faster in the last years. In the last decades of the twentieth century, companies’ main focus was centered around the increase of productivity ensuring, at the same time, the welfare of the individual (Gibson, Ivancevich & Donnelly, 2000). This has led to employees becoming an essential and sustainable basis for an organization’s competitiveness (De la Rosa-Navarro & Carmona-Lavado, 2010). In their organizational culture, most companies emphasize the importance of human capital and the strategic priority that is given to it. In this sense, the differentiation based on tangible attributes has become increasingly complicated, causing the need to have more qualified, professional, and satisfied employees (Gutiérrez Broncano & Rubio Andrés, 2009). On this matter, in a globalized and highly competing environment, human capital is the element that marks the achievement and development of competitive and sustainable advantages in the field of business efficiency.

Employees are possible compliers of the requirements that the theory of resources and capacities indicates are necessary to generate a competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). However, how can motivation and job satisfaction be developed to make employees more effective and efficient? Basically, it can be said that through the management of human resources (human capital) (Lepak & Snell, 1999). Human resource management is necessary to develop skills, generate new knowledge, promote cohesion in work teams, etc., ultimately, to transform people’s capacity, knowledge, and creativity into tangible results. Thus, the business paradigm of adaptation to change has a clear human dimension (Calderón Hernández, Naranjo Valencia & Álvarez Giraldo, 2010) since a company’s success is and will only be possible if measures to integrate workers into business projects are known, analyzed, and implemented, in order for all employees to consider the corporate objectives as their own and, at the same time, if the business objectives take into account the individual objectives that motivate each of its employees. In this way, people are no longer the most important asset of the organization; they are the organization itself (Rodríguez Serrano, 2000).

This current and future vision of organizational success through human resources is even more important, if that's possible, in tourism companies, where their management presents indubitable singularities with respect to other types of companies of different sectors. Tourism enterprises have to be understood as service companies, where their efficient management is highly conditioned, among other issues, by the importance of people (customers and employees) in the adequate provision of the service, given its heterogeneous nature (Gallego Agueda & Casanueva Rocha, 2010). Thus, in the tourism sector, the human factor is the key element because it is part of the “product” and directly performs the service provided by the companies. This could be limited to the study of business organization and management. However, it is necessary to go beyond this, in other words, to consider employees as different and unique people who come to an organization due to a series of expectations and needs, which they expect to fulfill through it (Morgan, 1997). Some organizations have been concerned about keeping their employees, recognizing their contributions (Lee & Chang, 2008). One of the main ways to achieve this is by ensuring that individuals achieve job satisfaction even though this might not be easy to attain (Moynihan & Pandey, 2007).

The construct of job satisfaction has been conceptualized in many ways, but perhaps the most appropriate is one that understands it as an attitude or set of attitudes developed by employees towards their situation at work. These attitudes can be referred to work in general or to specific facets of it (Bravo, Peiró & Rodríguez, 1996). Hence, it is basically conceived as a globalizing concept that refers to people’s attitudes towards various aspects of their work (Guzmán Delfino, Pontes Macarulla & Szuflita, 2015), and its presence is fundamental in the tourism factor, not only in terms of people’s desirable well-being, but also in terms of productivity and quality (Chiang, Núñez & Carolina Huerta, 2007). Schneider (1985) identifies some reasons that explain the considerable attention devoted to job satisfaction; among them, that it is an important result of organizational life, appearing in several studies as a significant predictor of important dysfunctional behaviors, such as: absenteeism, change of position and of organization. In line with de Castro and de Castro (2008), progress in understanding the factors of job satisfaction in these organizations will allow the development of possible actions to improve the level of workers’ satisfaction, having clear implications in the competitive success of the organizations.

Having defined the importance of job satisfaction, this article aims to determine, through the presentation and contrast of hypotheses, the influence of sociodemographic variables (such as: gender, age, education, and marital status) on employees’ job satisfaction in the field of tourism, specifically in the hotel sector of the city of Cuenca (Ecuador). Thus, the present study has been structured starting with an introductory section, followed by the conceptualization of the construct with the proposal of the hypotheses, to the description of the geographical area focus of the field study, then the methodology used to verify the hypotheses, leading to highlight the most outstanding results extracted. Finally, the conclusions reached, the limitations of the study, and possible future lines of research are presented.

Although job satisfaction has been a widely studied variable in the field of organizational behavior, there is no consensus on its definition; furthermore, even some classical theorists (Seashore, 1974, among others) consider that this concept is free of theory or that there is no comprehensive doctrine regarding what leads to job satisfaction. It is one of the oldest concepts in workplace psychology and, at the same time, one of the most controversial (Bell & Weaver, 1987; Cabello Espada, Algarra Costela, Díaz Arrabal, & Olmo Collado, 2015). However, its study should not be limited to a specific discipline, since this concept has been analyzed from an economic, psychological, and managerial perspective, giving it an interdisciplinary nature. Ivancevich and Donelly (1968) argued that each researcher understands job satisfaction differently, although this basically leads to a very similar concept. In fact, a certain common denominator is perceived, making it possible to categorize it into two different perspectives.

The first perspective would encompass those researchers who conceive job satisfaction as an emotion, attitude, or affective response. In their studies, detailed later, continuous references are found about the terms: emotional response, attitude toward work, feelings generated by the position held, etc. Concretely, these attitudes refer to evaluation statements (favorable or unfavorable) of objectives, people, or events. They reflect how someone feels about something. When the statement "I like my job" is made, an attitude toward work is expressed (Robbins & Judge, 2009). It has been relatively common for researchers (Breckler, 1984; Crites, Fabrigar & Petty, 1994; among others) to suppose that attitudes have three components: cognition, affection, and behavior.

Among classic authors who defend this vision of satisfaction, Katzell (1964) stands out; he concludes that if there is any consensus regarding the definition of job satisfaction, it is that of an expression of evaluation made by an individual about his or her own job. For his part, Locke (1969) asserts that job satisfaction is an agreeable emotional state, the result of job evaluation as a means to facilitate or help reach an individual’s work principles. Dissatisfaction is the negative emotional state which results from the evaluation of work as a means that frustrates or blocks the attainment of those principles.

In the current 21st century, Miñarro I Brugera et al. (2001) propose an ampler definition when considering that job satisfaction is composed of the behaviors, sensations, and feelings that the members of an organization have about their job, focusing on: individual perception, people’s affective evaluation about work regarding an organization, and the consequences that are derived from that sensation. In the same way, Andresen, Maike, and Cascorbi (2007) refer to the construct as a pleasant or positive emotional state, the result of the experience at work, which is produced when certain individual requirements are met through it. Lee and Chang (2008) understand job satisfaction as a broad and general concept that refers to the attitude of the individual towards his/her job; in short, it is the result of the worker's experience in his/her interaction with the organizational environment (Abrajan Castro, Contreras Padilla, & Montoya Ramírez, 2009; Pupo Guisadod & García Vidal, 2014).

The second perspective supposes a different and complementary vision to the previous one, conceiving job satisfaction as the result of a comparison. It is determined as an affective reaction toward work, which results from a comparison made by the employee between the current results at work with those he wants (or considers he or she deserves) to achieve. Wright (2006, p. 70) points out that job satisfaction “represents an interaction between employees and their work environment, where coherence is pursued between what employees want from their work and what employees feel they receive”. Gowler & Legge (1972) add a term to the elements that intervene in measuring job satisfaction, when considering that past employment experiences also provoke retrospective evaluations and feelings in the individual. Thus, not only the confrontation between expectations and contributions from the organization will measure satisfaction, but past experiences also have to be added to this intersection. In this line, Lévy-Garboua and Montmarquette (2004) base their definition of job satisfaction on the assumption that the employee who expresses satisfaction with his or her job evaluates his/her past experience as well as the likelihood that the current employment will continue in the future under the best possible conditions. Continuing with the idea of favorable or unfavorable perspectives, Morillo Moronta (2006) introduces, in regards to the degree of agreement between expectations with regards to work, the rewards it offers, the interpersonal relationships, and the managerial style.

Nevertheless, not all scientific research has been chosen the first or second perspective; there is a third line of research on job satisfaction from the perspective of group vision. Hence, Mason and Griffin (2002) emphasize that since many processes in organizations are undertaken in groups, it would be appropriate to conceptualize job satisfaction at the group and organizational level, as the attitude shared by said group for its attainment and towards the work environment it is associated with. Therefore, their understanding of the concept of job satisfaction goes beyond the individual, which is fully applicable in the current business field, where the concept of group work, team, or project presents itself as more efficient than individual work (philosophy 1+1 = 3). Said group satisfaction also entails an improvement of the group's organizational commitment and, accordingly and in a certain way, an improvement in the loyalty and job stability of the organization as a whole.

On the other hand, the analysis of the causes of job satisfaction or dissatisfaction has become an area of social interest among researchers (Grueso Hinestroza, 2009). Job satisfaction is not influenced by the same variables in all kinds of industries and services (Rahman & Zanzi, 1995); hence the need to focus on research that centers its attention on the tourism sector in general, and the hotel sector in particular, to achieve relevant conclusions for them. Managers and executives of the hotel industry should know the thoughts of their employees as well as their concerns (Chiang, 2010). In the words of Lee & Way (2010), hospitality managers need to know and evaluate the factors that play an important role in providing what workers expect from their jobs. Moreover, businesses should take care of each work area and provide a personalized improvement program aimed at the different groups according to their job characteristics. With these premises, researchers and professionals in the hotel industry have the need to find effective ways to measure the factors affecting workers’ job satisfaction.

The existing relationship between external customer satisfaction and internal customer (employees) satisfaction has been demonstrated in practice in numerous occasions in the tourism area in general as well as in the hotel sector in particular. There is empirical evidence that customer satisfaction is, to some extent, the result of employee satisfaction (Schlesinger & Heskett, 1991, Larson & Shina, 1995, among others). Therefore, the human factor must be incorporated in the management of service quality if we want it to improve. The link between the external customer and the employee is found in the satisfaction of both and in the continuity of their relationship; the lower the employee turnover, the greater the continuity in the relationship with the client, and the greater loyalty of both towards the company (Schlesinger & Heskett, 1991).

Having reviewed the literature regarding the construct object of analysis, the purpose of this study is to analyze employees’ job satisfaction in the hotel sector in the city of Cuenca (Ecuador). A statistical methodology has been applied, specified in the methodological section, which will allow us to detect the existence or not of relationships among certain variables of the individual and the job satisfaction expressed by employees:

Hypothesis 1: The gender variable does not influence job satisfaction. Although the fact that women are more satisfied than men in some activity sectors is a constant result (Sloane & Williams, 2000; Kaiser, 2002; Carrillo-García, Solano-Ruíz, Martínez-Roche, & Gómez-García, 2013), the most relevant specific studies related to the hotel sector (Frye & Mount, 2007; Jabulani, 2001) show the inexistence of a significant statistical relationship between gender and job satisfaction; hence, the veracity of this proposal will be contrasted in this empirical research.

Hypothesis 2: Age has a linear and progressive relationship with job satisfaction. Although age / job satisfaction relationships of various types have been detected, the most recent studies (among them Sarker, Crossman, & Chinmeteepituck 2003; Eskildsen, Kristensen, & Westlund, 2004; Cifuentes Rodríguez & Manrique Abril, 2014) defend this form of dependency. This vision has been followed in the formulation of this hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: Married status results in a lower level of satisfaction. Some studies have found no relationship between marital status and job satisfaction (Bilgic, 1998; Sinacore-Guinn, Akçali, & Fledderus, 1999). However, most of the studies analyzed have shown less satisfaction among married workers (Arias Gallegos & Justo Velarde, 2013; Gazioglu & Tansel, 2006; Kaiser, 2002). Nevertheless, it should be pointed out that the study of the literature could have considered this hypothesis inversely and even without determining any relationship.

Hypothesis 4: Educational level has a negative effect on satisfaction. As in the previous hypothesis, the results of the studies analyzed disagree in their conclusions. However, following the reasoning of various key researchers (Gazioglu & Tansel, 2006; Grund & Slivka, 2001; McGuinness & Sloane, 2011), according to patterns of personal and professional aspiration, academic qualifications tend to vary expectations since the higher the education (especially of younger workers), the greater the chances of dissatisfaction with unattractive routine tasks or tasks with little autonomy and power, which leads us to propose the hypothesis in these terms.

In 2015, Ecuador received 1,560,429 foreign tourists, mainly from Colombia (23.64%), the United States (16.66%), and Peru (11.27%), among others. The tourism activity is becoming an important economic engine for the country, contributing to its economy with 1,691.2 million dollars in 2015 (Ministerio de Turismo del Ecuador, 2016).

Cuenca, in Azuay province, has an approximate population of 500,000 inhabitants. The third largest city in Ecuador after Quito and Guayaquil, Cuenca is located in the Andean mountain range at an altitude of 2.560 meters above sea level. Its historic center includes important colonial and Republican-era buildings as well as colonial-inspired architectural elements such as balconies made of carved wood and wrought iron and cobblestone streets, and a European-flavored architecture without leaving behind native elements. Due to its historical and patrimonial richness, the city was declared as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1999. In addition, this city is pioneer in the artisan elaboration of the “Toquilla” straw hat, which has also been part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity since 2012.

The hotel sector employs 1,434 workers in the province of Azuay (Ministry of Tourism of Ecuador, 2015), and there are 242 hotel establishments in the city of Cuenca (table 1) with a total of 3,953 rooms. The accommodation capacity in the city has grown significantly in recent years from 130 hotel establishments in 2011 to 242 in 2015 (Cuenca’s Strategic Tourism Plan, 2016).

Table 1

Number of hotel establishments in Cuenca (2015)

Type of hotel |

||||

Category |

Hotel or resort |

Hostel or boarding house |

Hostel or motel |

Total |

Luxury |

8 |

65 |

|

73 |

First |

21 |

68 |

3 |

92 |

Second |

20 |

49 |

6 |

75 |

Third |

2 |

|

|

2 |

Total |

51 |

182 |

9 |

242 |

Note. Source: Cuenca’s Strategic Tourism Plan, 2016

As its source of data for the research, this study has used field work consisting of a survey applied to employees of hotel establishments of different categories in the city of Cuenca (Ecuador). The data with the hotel establishment typology where the surveys were conducted are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

Category of Hotel Establishments Surveyed

Type of hotel establishment |

||||

Category |

Hotel or resort |

Hostel or boarding house |

Hostel o motel |

Total |

Luxury |

22 |

17 |

0 |

39 |

First |

50 |

6 |

1 |

57 |

Second |

135 |

14 |

69 |

218 |

Third |

6 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

Total |

208 |

42 |

70 |

320 |

Note. Author’s elaboration

A simple random sampling methodology was used to select the interviewees among the workers of the hotel establishments, which accepted to conduct the survey. This methodology is used where subjects are selected based on the accessibility and proximity to the researcher, in a determined space and time (Alaminos & Castejón, 2006). A sample was attempted based on: the number of hotels, hotel categories, and hotel rooms in the city of Cuenca, according to the information obtained from the Ministry of Tourism of Ecuador (2015). Initially, before conducting the questionnaire, permission was requested from the management of the hotels, with some rejection, for which the results might present a certain bias, which does not significantly alter the representativeness of the results. The surveys were distributed along with a letter of presentation of the research and an action protocol to hotel managers or those responsible for the human resources area. The surveyors distributed the questionnaire to the employees, who filled it out without any intervention. Then, the questionnaires were collected ensuring the confidentiality of the information obtained. The field work was conducted between November 2015 and January 2016.

The survey was based on previous work by Weiss, Dawis, and England (1967), Porter and Smith (1970), Sánchez-Cañizares, López-Guzmán, and Millán (2007), and González-Santa Cruz, López-Guzmán, and Sánchez-Cañizares. (2014). The questionnaire is structured in three blocks: (1) data about the job position, such as: the type of contract, dedication, seniority, department, shift, salary; (2) issues related to job satisfaction, such as: the reason for engaging in the activity, advantages and disadvantages of the profession, level of satisfaction with regard to aspects related to the activity, or level of general satisfaction; (3) analysis of the employees’ socio-demographic characteristics, such as: age, marital status, nationality, training. Closed-ended questions were used in the questionnaire to choose between different options, preferably in the employee’s socio-economic study and the data about job position. Assessment questions used a Likert scale of five points to evaluate job satisfaction.

The total number of questionnaires filled out was 328, of which 320 were validated. No stratification has been conducted for the variables of sex, age, department or training. The data collected was organized, tabulated, and analyzed using the SPSS 22.0 program for Windows.

Table 3 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the employees surveyed according to sex, age, place of origin, professional category, educational level, and economic income.

Table 3

Sociodemographic Aspects of the Survey

Variables |

|

Percentage |

Variables |

|

Percentage |

Gender (N = 320) |

Man Woman |

44.4% 55.6% |

Type of contract (N=320) |

Permanent contract Temporary contract |

91.9% 8.1% |

Age (N = 320) |

16-29 years 30-39 years 40-49 years 50-59 years 60 or older |

42.5% 27.2% 21.3% 7.5% 1.6% |

Rent (N = 320) |

Less than $400 From $401 to $700 From $700 to $1.000 From $1.001 to $1.300 From $1.301 to $1.600 More than $1.601 |

42.5% 50.9% 4.4% 0.9% 0.9% 0.3% |

Department (N = 320) |

Administration Accounting Restaurant/ catering Reception/ Concierge Maintenance Housekeeping Kitchen Executive Other |

8.1% 4.4% 17.8% 22.5% 7.5% 20.0% 17.2% 0.3% 2.2% |

Level of education (N = 316) |

Incomplete Elementary Schooling Elementary Schooling Incomplete High School High School Technical level University degree |

1.6%

13.4% 15.3%

38.4% 8.4% 22.7%

|

Work shifts (N=320) |

Morning Afternoon Night Rotating shift Morning and afternoon Afternoon and night |

17.8% 6.6% 4.1% 30.0% 34.1% 7.5% |

Work hours (N=320) |

Full time Part time |

91.9% 8.1% |

Note. Author’s elaboration

A greater number of women than men were surveyed (55.6% versus 44.4%), which significantly differs from Ecuador’s general statistical data (Ministerio de Relaciones Laborales. Dirección de Comunicación Social, 2015), where the rate of adequate / full employment for men is 16.4 percentage points higher, breaking in this way, gender inequality in terms of occupation, although, the salary they receive is lower.

More than two thirds of those surveyed are under 40 years of age (69.7%), of whom 42.5% are under 30 years, the average age of employees being 33.9 years old. Despite the young average age, it is slightly higher than the average age in Ecuador, which is 28.4 years (National Institute of Statistics and Census, 2016). This youth confers this sector a great potential for progress, which is also linked to experience, since the average length of service in the hotel and catering industry of those surveyed is 6.9 years. In this case, there is also a difference in age by gender; female employees are older (average 34.8 years) than male employees (average 32.7 years), although they present similar seniority in the sector: 6.9 years for women compared to 6 years for men.

Most of the employees are Ecuadorian citizens (95.9%), and only 0.6% of those surveyed are from non-Latin American countries. Regarding the type of contract employees have, 91.9% said they had a permanent contract, which is often connected to greater personal satisfaction (Chadi & Hetschko, 2013) and emotional attachment to the company (Buonocore, 2010). Making a differentiation by gender, 92.7% of women have a permanent contract in contrast to 90.8% of men.

The vast majority of those surveyed have full-time (91.9%) and flexible working hours; 34.1% indicate they work morning and afternoon hours; 30.0% state they work rotating shifts, while employees who work morning or afternoon hours are few (17.8% and 6.6% respectively), with an average of 42.4 hours of work per week. Of these, part- time employees work 28.5 hours, while full-time employees work an average of 43.6 hours.

There is a marked bipolarity in wages, with the dividing line being $400. Forty-two point five percent of the workers have a salary lower than 400 dollars, lower than the average salary in Ecuador, which is approximately 460 dollars (Ministerio de Relaciones Laborales. Dirección de Comunicación Social, 2015), while 50.9% of those surveyed have a salary between US$401 and US$700. Only 2.1% have a salary higher than $1.000. An association between gender and wage has been detected (Pearson’s Chi-square coefficient χ2 = 9,460; p = 0.048); if 49.9% of women receive a salary lower than 400 dollars, this percentage drops to 33.8% in the case of men.

In order to test the first research hypothesis where the gender variable does not influence job satisfaction, first, a Chi-square Pearson's contrast of relationship between the variables of gender of the surveyed worker and general satisfaction with his or her job was carried out. The result of this statistic χ2 (1,374; p=0.842) for four degrees of independence, indicates the fulfillment of the null hypothesis of independence between the variables; consequently, it is accepted that there is no relationship between job satisfaction and the gender of the respondents. The average satisfaction between men and women is similar: 4.14 points over 5 for women compared to 4.13 for men (Table 4). At the same time, the Mann-Whitney U test, a technique used in these cases where the assumption of normality is not verified, indicates the absence of significant differences between the averages of each category with a p-value of 0.764. These results are consistent with the work of Frye & Mount (2007), and Jabulani (2001).

Table 4

Satisfaction by Gender

Gender |

N |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

p-values Mann-Whitney |

Male |

142 |

4.13 |

0.752 |

0.764 |

Female |

178 |

4.14 |

0.794 |

Note. Author’s elaboration

Table 5 shows the percentage ratio according to the five-point Likert scale of the degree of general satisfaction, where it is observed that the main difference is found with the option "very satisfied." It receives the highest choice by women, while the option "quite satisfied" is higher in the case of men.

Table 5

Degree of General Satisfaction according to Gender

Gender |

Very dissatisfied |

Dissatisfied |

Somewhat satisfied |

Quite satisfied |

Very satisfied |

Man |

0.7% |

0.7% |

16.2% |

50.0% |

32.4% |

Women |

0.6% |

1.7% |

16.9% |

44.9% |

36.0% |

General |

0.6% |

1.3% |

16.6% |

47.2% |

34.4% |

Note. Author’s elaboration

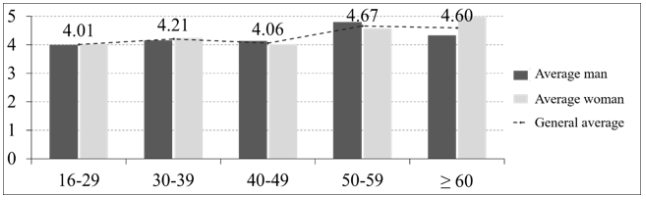

In order to verify the second research hypothesis regarding the existence of a linear relationship between age and job satisfaction, a preliminary analysis was carried out using contingency tables on average satisfaction by age brackets, using a Person’s Chi-square contrast, also analyzing it by gender. Although at a general level a relationship between age and job satisfaction of those surveyed can be confirmed (χ2= 44,413; p=0.000), the analysis by gender provides different results. While in the case of female workers there is a relationship between age and job satisfaction (χ2= 30,201; p=0.017), the same cannot be said of male workers (χ2= 22,078; p=0.141). The Somers' D and Kendall Tau-c tests are not significant; thus, it is not possible to deduce that the older workers are, the more or less job satisfaction.

From an observation of Figure 1, it is not possible to assert that the hypothesis of a linear and progressive relationship is met when the data is analyzed as a whole, and the adjustment done by ordinary minimum square method did not yield significant values. The figure for job satisfaction in women shows a slight decrease in the 40 to 49-year-old bracket, to later progressively increase as the age of the respondent’s increases. This behavior differs from that of male workers, who present a positive tendency in the general degree of satisfaction from the first age brackets (16-29 years old) to 60 years old, although without a significant linear relationship, for which it is not possible to reliable confirm the hypothesis by Sarker et al. (2003), Eskildsen et al. (2004) or Cifuentes Rodríguez and Manrique Abril (2014). In the case of respondents older than 60 years old, no conclusions can be made due to the minimum number of respondents (5 surveys); therefore, this analysis has not been done in this study to avoid possible distortions to the results.

Figure 1

Average satisfaction by age brackets

* The coefficients are significant at levels *p<0.05.

Note. Author’s own elaboration.

It was found through an analysis of contingency tables that, although there is no significant relationship between overall employee satisfaction and their marital status (χ2= 3,343; p=0.101), married employees have lower levels of overall satisfaction than single or divorced employees (Table 6). However, despite these differences in assessment, it is not possible to reject the hypothesis of equality of satisfaction based on marital status (Krustal-Wallis test = 2,174; p= 0.337). The analysis by gender give similar results to those obtained in the whole of those surveyed. Thus, it is possible to accept the hypothesis of less satisfaction in married respondents (Arias Gallegos & Justo Velarde, 2013; Gazioglu & Tansel, 2006), although partially and inconclusively.

Table 6

Satisfaction by Marital Status

|

Men |

Women |

General |

|||

|

Average |

Standard Deviation |

Average |

Standard Deviation |

Average |

Standard Deviation |

Single |

4.16 |

0.682 |

4.24 |

0.671 |

4.20 |

0.674 |

Married |

4.09 |

0.804 |

4.05 |

0.870 |

4.07 |

0.835 |

Divorced |

4.29 |

0.756 |

4.25 |

0.851 |

4.26 |

0.813 |

Pearson Chi-Square |

5,459 (0.708) |

10,318 (0.243) |

3,343 (0.101) |

|||

Krusk-Wallis test |

1,798 (0.783) |

1,798 (0.407) |

2,174 (0.337) |

|||

Note. Author’s own elaboration

Table 7 presents the degree of satisfaction based on the different levels of education. Although not rigorously, the analysis yielded that the employees’ higher or lower level of education does affect the level of overall job satisfaction (χ2= 32,567; p=0.038) of those surveyed. Moreover, this satisfaction is inversely correlated to their level of education. The Somers' D and Kendall Tau-c coefficients, which appear with their corresponding critical levels of significance, ratify that both variables are related (see Table 8). The correlation is negative, which allows the inference that a higher level of education corresponds to a lower average satisfaction (Gazioglu & Tansel, 2006; Grund & Slivka, 2001; McGuinness & Sloane, 2011), accepting the hypothesis in the terms proposed, although this relationship is weak due to the scant value of the measurements of the statisticians cited. It has been noted that this inverse job satisfaction relationship is met in the case of men, but not in the case of women.

Table 7

Satisfaction according to Level of Education

|

N |

Average Satisfaction |

Standard Deviation |

Incomplete elementary schooling |

5 |

4.80 |

0.447 |

Elementary schooling |

43 |

4.42 |

0.698 |

Incomplete High School |

49 |

3.94 |

0.899 |

High School |

123 |

4.14 |

0.761 |

Technical School |

27 |

4.15 |

0.534 |

University or higher |

69 |

4.04 |

0.789 |

Note. Author’s own elaboration

-----

Table 8

Procedure Statistics and Symmetrical Measurements

of Job Satisfaction and Level of Education

|

Pearson Chi-square |

d de Sommers |

Tau-c de Kendall |

General |

32,567 (0.038*) |

-0,099 (0.047*) |

-0,086 (0.047*) |

Men |

26,590 (0.147) |

-0,184 (0.021*) |

-0,155 (0.021*) |

Women |

19,469 (0.492) |

-0,043 (0.504) |

-0,037 (.504) |

*Significant at 5%

Note. Author’s own elaboration

The high performance of current organizations is based on the ability to integrate workers into the business project so that they consider the corporate objectives of the company as their own. The hotel industry needs to understand that employees do not respond only to a salary, but also to other factors that influence their motivation and satisfaction. Knowledge of these factors is of key interest for business success, since this sector is characterized by its intense contact between employees and clients; employees are a fundamental part of the image these clients will have of a hotel establishment. Therefore, employees’ satisfaction would have an impact not only on the quality of the service, but also on the attitude towards the service provided by establishments. In this vein, it is important for companies to maintain their employees satisfied in order to foster customer loyalty.

This study was aimed to contribute towards alleviating the lack information found in the field regarding job satisfaction in the hotel sector in the Republic of Ecuador, and specifically in Cuenca, a city declared a World Heritage Site and a major tourist sector.

Among the main socio-demographic characteristics found in this study, the youth of the workforce and a greater number of women than men in this sector stand out, in contrast to the statistical data on labor activity in Ecuador. This higher presence of women is not correlated to equal pay, as women tend to have jobs with lower salaries than their male counterparts; however, wages in this sector are generally relatively low.

Considering the socio-demographic characteristics aforementioned, despite the wage and socio-demographic differences found between both sexes, the empirical results of this study have not verified any evidence of a significant statistical relationship between job satisfaction and the gender of hotel sector employees. A relationship between age and job satisfaction can be verified, but no significant graphic relationship can be found as has been the case of other studies, there being a different behavior based on the gender of those surveyed. In the case of men, job satisfaction increases progressively with age, while this is not the case for women.

Although descriptive results could not be confirmed by significance analyses, married employees have lower levels of job satisfaction than single or divorced workers. This result highlights the need to delve deeper into the cause that produces this lower degree of satisfaction in this group. Additionally, the data obtained suggests that the average level of satisfaction decreases with the increase of the respondent’s education level, especially in the case of men; however, the low level of satisfaction that female workers with incomplete formal instruction present is remarkable.

The main limitation of this research is due to the geographical scope of the study, the city of Cuenca (Ecuador), since it does not allow a generalization of these results. Therefore, it would be desirable to extend this study to the main cities of Ecuador, in order to develop statistical sources that allow the description of labor actions aimed at improving the employees’ welfare. Future research could analyze the relationship between job position or organizational variables on job satisfaction and how it influences variables that define an organization’s success, such as performance, organization commitment, among others.

ABRAJAN CASTRO, María G., CONTRERAS PADILLA, José M. y MONTOYA RAMÍREZ S. Grado de satisfacción laboral y condiciones de trabajo: una exploración cualitativa. Enseñanza e Investigación en Psicología, 14(1), (2009), pp. 105-118.

ALAMINOS, A. y CASTEJÓN, Juan L. Elaboración, análisis e interpretación de encuestas, cuestionarios de escalas de opinión. Serie docencia universitaria-EEES. (2006). Alcoy: Marfil. Recuperado de <https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/20331/1/Elaboraci%C3%B3n,%20an%C3%A1lisis%20e%20interpretaci%C3%B3n.pdf>

ANDRESEN, Maike; DOMSCH, Michel E. y CASCORBI, Annett H. Working Unusual Hours and Its Relationship to Job Satisfaction: A Study of European Maritime Pilots. Journal of Labor Research, (2007), 28, pp. 714-734.

ARIAS GALLEGOS, Walter L. y JUSTO VELARDE, Oscar. Satisfacción Laboral en Trabajadores de Dos Tiendas por Departamento: Un Estudio Comparativo. Ciencia & trabajo. 15(47), (2013). Recuperado de <http://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=S0718-24492013000200002 &script=sci_arttext>

BARNEY, Jay. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management. 17 (1), (1991), pp. 99-120.

BELL, Richard C. y WEAVER, Jhon R. The dimensionality and scaling of job satisfaction: An internal validation of the Worker Opinion Survey. Journal of Occupational Psychology. 60(2), (1987), pp. 147-155.

BILGIC, Reyhan. The relationship between job satisfaction and personal characteristics of Turkish workers. Journal of Psychology. 132 (5), (1998), pp. 549-557.

BRAVO, M. J., PEIRO J. M. y RODRIGUEZ, I. Satisfacción Laboral. En Peiró, J. M. y Prieto, F. (eds.): Tratado de Psicología del Trabajo. Vol. I. La actividad laboral en su contexto, (1996), pp. 343-394. Síntesis: Madrid

BRECKLER, Steven J. Empirical Validation of Affect, Behavior, and Cognition as Distinct Components of Attitude. Journals of Personality and Social Psychology. 5(84), (1984), pp.1191-1205.

BUONOCORE, Filomena. Contingent work in the hospitality industry: A mediating model of organizational attitudes. Tourism Management. 31(3), 2010, pp. 378-385.

CABELLO, Eva M, ALGARRA COSTELA María. DÍAZ ARRABAL, Pablo R. y OLMO COLLADO, David. Nivel de satisfacción laboral según la categoría laboral. REIDOCREA. 4, (2015), pp. 200-205.

CALDERÓN HERNÁNDEZ, Gregorio., NARANJO VALENCIA, Julia C. y ÁLVAREZ GIRALDO, Claudia M. Gestión humana en la empresa colombiana: sus características, retos y aportes. Una aproximación a un sistema integral. Cuadernos de Administración. 23 (41), (2010), pp. 13-36.

CARRILLO-GARCÍA, Cesar. SOLANO-RUÍZ María C., MARTÍNEZ-ROCHE María E. y GÓMEZ-GARCÍA, Carmen I. Influencia del género y edad: satisfacción laboral de profesionales sanitarios. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 21(6), (2013), pp. 1314-1320.

DE CASTRO, Emilio J. y DE CASTRO, Francisco J. Universidad, Sociedad y Mercados Globales. Comunicación presentada en la Asociación Europea de Dirección y Economía de Empresa International Conference. 17, (2008), pp. 563-575.

DE LA ROSA NAVARRO María D. y CARMONA-LAVADO, Antonio. Cómo afecta la relación del empleado con el líder a su compromiso con la organización. Universia Business Review. 2(26), (2010), pp. 112-132.

CHADI, Adrian, y HETSCHKO, Clemens. Flexibilisation without hesitation? Temporary contracts and workers' satisfaction. IAAEU Discussion Paper Series in Economics, (2013). Disponible en: <https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/ 10419/ 80870/ 1/739960717.pdf>

CHIANG, Chun F. Perceived organizational change in the hotel industry: An implication of change scheme. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 29, (2010), pp. 157-167.

CHIANG, María M., NÚÑEZ Antonio y HUERTA, Patricia C. Relación del clima organizacional y la satisfacción laboral con los resultados, en grupos de docentes de instituciones de educación superior. Icade. Revista cuatrimestral de las Facultades de Derecho y Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales, 72, (2007) pp. 49-74.

CIFUENTES RODRÍGUEZ, Johana E. y MANRIQUE ABRIL, Fred G. Satisfacción laboral en enfermería en una institución de salud de cuarto nivel de atención, Bogotá, Colombia. Avances en Enfermería. 32 (2), (2014) pp. 217-227.

CRITES, Stephen L., FABRIGAR Leandre R. y PETTY, Richard E. Measuring the Affective and Cognitive Properties of Attitudes: Conceptual and Methodological Issues. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 12, (|1994), pp. 619-634.

ESKILDSEN, Jacob K., KRISTENSEN Kai y WESTLUND, Anders H. Work motivation and job satisfaction in the Nordic countries. Employee Relations. 26, (2004), pp.122-136.

FRYE, William D. y MOUNT, Daniel J. An examination of job satisfaction of general managers based on hotel size and service type. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism. 6(2), (2007), pp. 109-134.

GALLEGO AGUEDA, María A. y CASANUEVA ROCHA, Cristobal. Dirección y organización de empresas turísticas. (2010). Ediciones Pirámide, Madrid.

GAMERO, Carlos. Satisfacción laboral y tipo de contrato en España. Investigaciones económicas. 31(3), (2007), pp.415-444.

GAZIOGLU, Saziye y TANSEL, Aysit. Job satisfaction in Britain: individual and job related factors. Applied Economics. 38(10), (2006), pp. 1163-1171.

GIBSON James L., IVANCEVICH John M., DONNELLY, James H. Organizations: Behavior, Structure, Processes. (2000), McGraw-Hill: Boston.

GONZÁLEZ SANTA CRUZ, Francisco, LÓPEZ-GUZMÁN, Tomás. y SÁNCHEZ CAÑIZARES, Sandra M. Analysis of Job Satisfaction in the Hotel Industry: A Study of Hotels in Spain. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism. 13(1), (2014) pp. 63-80.

GOWLER, Dan y LEGGE, Karen. The internal labour market and the property to stay. Research into the behaviour of the labour market. Doc. HS/H/201/399, OCDE. (1972), pp. 6-9.

GRUESO HINESTROZA, Merlín P. La discriminación de género en las prácticas de recursos humanos: un secreto a voces. Cuadernos de Administración. 22(39), (2009) pp.13-30.

GRUND, Christian y SLIWKA, Dirk. The impact of wage increases on job Satisfaction-Empirical evidence and theoretical implications. IZA Discussion Papers. 387, (2001) pp. 1-17. <Disponible en: ftp://repec.iza.org/dps/dp387.pdf>

GUTIÉRREZ BRONCANO, Santiago G. y RUBIO Andrés, M. El factor humano en los sistemas de gestión de calidad del servicio: un cambio de cultura en las empresas turísticas. Cuadernos de Turismo. 23, (2009) pp. 129-147.

GUZMÁN DELFINO, Camila P., PONTES MACARULLA, Paula y SZUFLITA Magdalena. Empowerment y satisfacción laboral. REIDOCREA. 4, (2015), pp. 66-73.

INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADÍSTICAS Y CENSOS (2016). Censo de Población y Vivienda de 2010 de Ecuador. Disponible en: <http://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec //resultados/>

IVANCEVICH, John. M. y DONNELLY, James. H. Job satisfaction research: a manageable guide for practitioners. Personnel Journal. 47, (1968), pp. 172-177.

JABULANI, Ndhlovu. An examination of customer service employee’s self-efficacy, job satisfaction, demographic factors, and customer perception of hotel service quality delivery in Jamaica. (2001). Tesis Doctoral. Nova Southeastern University: Florida.

KAISER, Lutz C. Job satisfaction: a comparison of standard, non-standard, and self-employment patterns across Europe with a special note to the gender/job satisfaction paradox. (2002). EPAG, Working Paper, 27.

KATZELL, Raymond A. Personal values, job satisfaction and job behaviour. En Borow, H. (eds.): Man in a world at work. (1964), pp. 341-363, Houghton Mifflin: Boston.

LARSON, Paul D. y SINHA, Ashish. The TQM Impact: A Study of Quality Manager’s Perceptions. Quality Management Journal. 2(3), (1995), pp. 53-66.

MIÑARRO I BRUGERA, Jordi, VERDÚ, M. Angels, LARRAINZAR, M. Jesús y MOLINOS, Francisco J. La satisfacción laboral en el hospital de Sant Cugat de Asepeyo. Capital humano, 2001, vol. 143, p. 46-50.

LEE, Chang y WAY, Kelly. Individual employment characteristics of hotel employees that play a role in employee satisfaction and work retention. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 29 (3), (2010), pp.344-353.

LEE, Yuan D. y CHANG Huan M., Relations between Team Work and Innovation in Organizations and the Job Satisfaction of Employees: A Factor Analytic Study. International Journal of Management. 25 (4), (2008), pp. 732- 739.

LEPAK, David P. y SNELL, Scott. A. The human resource architecture: Toward a theory of human capital allocation and development. Academy of Management Review. 24 (1), (1999), pp. 31-48.

LEVY-GARBOUA, Louis y MONTMARQUETTE, Claude. Reported job satisfaction: what does it mean? The Journal of Socio-Economics. 33 (2), (2004), pp. 135-151.

LOCKE, Edwin A. What is job satisfaction? Organizational behavior and human performance. 1(4), (1969), pp. 309-336.

MASON, C. M. y GRIFFIN M. A. (2002). Group task Satisfaction: Applying the Construct of Job Satisfaction to Groups. Small Group Research. 33, (2002), pp. 271-312.

MCGUINNESS, Seamus y SLOANE, Peter J. Labour Market Mismatch Among UK Graduates: An Analysis Using REFLEX Data. Economics of Education Review. 30 (1), (2011), pp. 130-145.

MINISTERIO DE RELACIONES LABORALES. Dirección de Comunicación Social (2015). Disponible en <http://www.trabajo.gob.ec/el-salario-basico-para-el-2015-sera-de-354-dolares/>

MINISTERIO DE TURISMO DE ECUADOR (2016). Disponible en <http://www.turismo.gob.ec/resultados-del-2015-ano-de-la-calidad-turistica-en-ecuador/>.

MIÑARRO BRUGUERA Jordi, VERDÚ María A., LARRAÍNZAR María J. y MOLINOS ROSADO, Francico J. La satisfacción laboral en el hospital de Sant Cugat de Asepeyo. Capital Humano. 143, (2001), pp. 46-50.

MORILLO MORONTA, Iraiza. J. Nivel de satisfacción del personal académico del Instituto Pedagógico de Miranda José Manuel Siso Martínez en relación con el estilo de liderazgo del jefe del departamento. Sapiens, 7(1), (2006), pp. 43-57.

MOYNIHAN, Donald P. Y PANDEY, Sanjay K. Finding Workable Levers Over Work Motivation: Comparing Job Satisfaction, Job Involvement and Organizational Commitment. Administration & amp Society. 39 (7), (2007), pp. 803-832.

MORGAN, Gareth. Images of organization. (2 Ed.), (1997) Sage: Londres.

PORTER Lyman W. y SMITH Frank J. The Etiology of Organizational Commitment, (1970), Unpublished paper: University of California.

PUPO GUISADO, Beatriz y GARCÍA VIDAL, Gelmar. Relación entre el clima organizacional, la satisfacción laboral y la satisfacción del cliente. Caso hotel de la cadena Islazul en el oriente Cubano. Revista Caribeña de Ciencias Sociales. 10, (2014).

RAHMAN, Mawdudur y ZANZI, Alberto. A comparison of organizational structure, job stress, and satisfaction in audit and management advisory services (MAS) in CPA firms. Journal of Managerial Issues. 7 (3), (1995), pp. 290-305.

ROBBINS, Stephen P. y TIMOTHY, Judge. Comportamiento organizacional. (2009), Pearson: Educación, México 13ª edición.

RODRÍGUEZ-SERRANO, Juan C. Hacia nuevos modelos relacionales y universales de gestión de personas. (2000). Comunicación del 35º Congreso AEDIPE, 3-6 octubre, Barcelona.

SÁNCHEZ CAÑIZARES Sandra, LÓPEZ-GUZMÁN, Tomás y MILLÁN VÁZQUEZ DE LA TORRE, Genoveva. La satisfacción laboral en los establecimientos hoteleros. Análisis empírico en la provincia de Córdoba. Cuadernos de Turismo. (20), (2007), pp. 223-249.

SARKER, Shah J, CROSSMAN, Alf y CHINMETEEPITUCK, Parkpoom. The relationships of age and length of service with job satisfaction: an examination of hotel employees in Thailand. Journal of Managerial Psychology. 18 (7-8), (2003), pp. 745-758.

SEASHORE, Stanley E. Job satisfaction as an indicator of the quality of employment. Social Indicators Research. 1 (2), (1974), pp. 135-168.

SCHLESINGER, Leonard A. y HESKETT, James L. Breaking the cycle of failure in services. MIT Sloan Management Review. 32 (3), (1991), pp. 17-28.

SCHNEIDER, Benjamin.Organizational behaviour. Annual Review of Psychology. 36, (1985), pp. 573-611.

SINACORE-GUINN, Ada L., AKÇALI, Ozge. y FLEDDERUS, Susan W. Employed women: Family and work-reciprocity and satisfaction. Journal of Career Development. 25, (3), (1999), pp. 187-201.

SLOANE, Peter y WILLIAMS, Hector. Job satisfaction, comparison earnings and gender. Labour. 14, (2000), pp. 473-502.

WEISS, David J., DAWIS, Rene V. y England, George W. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire, Industrial Relations Center. (1976). University of Minnesota, Minnesota.

WERTHER, William B. y DAVIS Keith. Administración de recursos humanos. (2008). McGraw-Hill Interamericana.

WRIGHT, Thomas A. The emergence of job satisfaction in organizational behaviour. A historical overview of the dawn of job attitude research. Journal of Management History. 12 (3), (2006), pp. 262-277.

1. Faculty of Hospitality. Universidad de Cuenca (Ecuador). Research Department. Master in Communication and Marketing. ana.serrano@ucuenca.edu.ec

2. Faculty of Hospitality. University of Cuenca (Ecuador). Ph.D. in Administration. silvana.astudillo@ucuenca.edu.ec

3. Faculty of Law and Business Sciences. University of Cordoba (Spain). PhD. in Business Administration. guzman.munoz@uco.es

4. Faculty of Law and Business Sciences. University of Cordoba (Spain). PhD. in Business Administration. td1gosaf@uco.es