Vol. 39 (Number 46) Year 2018. Page 11

Vol. 39 (Number 46) Year 2018. Page 11

Andrea PRECHT 1; Ilich SILVA-PEÑA 2; Jorge VALENZUELA 3; Carla MUÑOZ 4

Received: 29/05/2018 • Approved: 14/07/2018

ABSTRACT: This paper purpose is to understand faculty’ representations of first-year students’ commitment to learning in Chilean Higher Education. The participants were sixteen professors who teach first-years students. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, and the corpus was analysed through Semantic Structural Analysis. Results show, the variety of students as perceived by faculty, and their diversity in their commitment to learning. It is discussed that this kind of understanding might be an obstacle to transforming effectively undergraduate students learning experiences. |

RESUMEN: Se propone comprender las representaciones sociales de los académicos respecto del compromiso de los estudiantes de primer año con su aprendizaje. Los participantes fueron dieciséis académicos que enseñan a estudiantes de primer año. Se realizaron entrevistas semi-estructuradas analizadas mediante Análisis Estructural Semántico. Los resultados muestran la percepción del profesorado universitario respecto de la diversidad entre estudiantes y sus diferencias en el compromiso con su propio aprendizaje. Se discute como estas representaciones pueden obstaculizar la transformación de experiencias de aprendizaje. |

Between the 1980s and today, Chilean higher education (CHE) has faced extensive changes, especially in the enrollment of student populations that traditionally have been excluded from its circuits. (Brunner, 2011; Concha, 2009; Marshall, 2010; 2006; Rodríguez-Ponce, Gaete Feres, Pedraja-Rejas, & Araneda-Guirriman, 2015; Slachevsky, 2015). During this period, the enrollment in higher education increased from 149.689 (OECD., 2013) to 1.152.125 (CNED, 2015) students, growing five times larger If only first-year students are considered, the actual population is 368.981 (CNED, 2015) students versus 44.492 during 1994 (CNED, 2011).

As a response to the critical aspects of acculturation to the massive context in undergraduate matriculation, government agencies have devised policies to redesign curriculums to this new settlement: develop soft skills, improve teaching for undergraduate studies, reduce dropout rates, and retain students in the system. In smaller scales, universities have started to implement local projects, such as centres for teaching and learning, remedial programs in language, mathematics, and writing, among others. Most of those efforts are centred around first-year students considering the national dropout rate is 30% for first-years students, (CNED, 2011), primarily lower-income students. In the Maule Region, this change from an elite-based HE to a massified, highly differentiated one has allowed families of rural peasants, fishers, seasonal workers, and artisans to access higher education (Concha, 2009).

During the 17-year period from 1973 to 1990, Chile was under the military rule of Pinochet. Until 1980, the higher education system was a small, elitist one funded by public resources (Cancino, 2010; Matear, 2006). Since then, CHE has faced in-depth changes, especially in the enrollment of student populations that traditionally have been excluded from higher education circuits (Brunner, 2011; Concha, 2009; Marshall, 2010; Matear, 2006; Rodríguez-Ponce et al., 2015).

Before 1980, there were only eight universities: two were public, and six were private. All of them were highly selective with a differentiated tuition fee, which has been introduced in 1973 by Pinochet regime (Rodríguez-Ponce et al., 2015).

In 1980, the neoliberal economic model was introduced into the public sector with the New Public Management model, including educational reform at all levels. This reform has two major components: financial and decentralisation. In the financial aspect, government funding decreases, and universities were required to finance themselves, mainly by charging tuition to students and their families (Donoso, Arias, Weason, & Frites, 2012; Marshall, 2010; Matear, 2006).The system was decentralised when all eight universities with parent establishments in the capital city were restructured, and their regional branches turned into independent universities. At the same time, the creation of new private universities with no state resources was stimulated; there were regulations for them. Since the return of democracy in the ‘90s, there have been established more regulation policies through accreditation systems and requirements for receiving state resources (Donoso et al., 2012; Marshall, 2010).These changes have been slowly set, the same as others reforms in Chilean society. All this brought a dramatic increase in student numbers and rapid growth in the range of universities and the programs they offer (OECD., 2013). The CHE system has professional institutes, technical training centres, and universities. The former two are all private, self-financed, and can earn profits; universities have a nonprofit status (OECD., 2013).

Currently, there are 59 Chilean universities, which can be classified as State-owned, State-subsided private universities (pre-‘80s, or part from a branch of pre-‘80s) and private universities (post-80s).

Even if the Chilean admission system to higher education relies on school grades and national standardised tests, not all the universities are selective (Santelices, Ugarte, Flotts, Radovic, & Kyllonen, 2011). There is an uneven supply provision in the system, in which 32% of the supply concentrates at the capital city of Santiago (Donoso et al., 2012). Most of the selective higher education institutions in the country can be found in Santiago (Donoso et al., 2012).

As was already established, the massification of CHE means that an important portion of first-year students at Talca are first-generation (FG). These are defined as those whose parents had no higher education studies or did not finish them; they might also have not finished high school (Dumais & Ward, 2010).Those students’ socialisations are different from the ones faced at the campus, lacking the necessary cultural capital for academic life (Bourdieu, 1998; Stuber, 2011; Wiggins, 2011). For the cultural capital inheritors, schooling is just an extension of their habitus; upon entering university culture, they are closer to that culture, their codes, their habits, and their customs. Their effort is to learn what is taught explicitly. Their social position gives the rest. Conversely, FG students not only have to learn what is taught explicitly but are faced with a double effort as they are required to deal appropriately with culture that is alien to them, acquiring it by effort, study, and diligence (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1995; Bourdieu, 1998a, 1998b; Stephens et al., 2012). These students are at risk concerning completing their studies (Black, 2015; Bosse, 2015; Martinez, Sher, Krull, & Wood, 2009), having higher dropout rates (Caldwell, 2010; Engle & Tinto, 2010; Espinoza Díaz & González, 2012), and in general, having a tendency to struggle academically (Castillo, 2010; Stephens, Fryberg, Markus, Johnson, & Covarrubias, 2012). Castillo (2010) pointed out that Chilean FG students’ access to higher education comes without a clear idea of what to expect from it.

Still, cultural capital is not the only factor that impacts FGs; the peer effect shows that the students’ academic performances could also be explained by their peers’ socioeconomic status, assimilating the average performance of their friends and adapting to a social norm of effort (Carrell, Fullerton, & West, 2008; Donoso & Schiefelbein, 2007; Lomi, Snijders, Steglich, & Torló, 2011; Lu, 2014).

For these students, initiatives that generate academic and social support networks enhance their chances of persistence, academic success, social integration, and retention (Padgett et al., 2012). Universities that implement good practices around campus have an impact on students’ cognitive growth, but those are different among students’ background characteristics and pre-college development, as well as by the institution attended (Kuh, 2008; Padgett, Johnson, & Pascarella, 2012; Seifert, Pascarella, Wolniak, & Cruce, 2006).

This study used a qualitative method, which allows us to reconstruct reality as the subjects signify it. Its aim is first to approach the phenomenon, in this case, university teachers’ social representations of first-year students’ commitment to learning in the context of the massification of Chilean higher education, specifically first-year students in Talca.

We interviewed faculty who teach first-year students from the four universities. Those faculties were affiliated to a state-owned, a state-subsided private university or one of two private universities.

We used the snowball sampling technique where initial key informants point out other informants until discourse saturation was reached (Atkinson & Flint, 2001; Flick, 2015; Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, 2014). That created a sample composed of sixteen professors (See table 1 for sample).

Table 1

Sample

|

University 1 |

University 2 |

University 3 |

University 4 |

Institution typology. |

State Owned (SO) |

State subsided private university (SSPU) |

Private (PU) |

Private |

Number of participants. |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

Academic program |

Pedagogy (1) |

Engineering (1) |

Psychology (1) |

Obstetrics (1) |

Psychology (1) |

Pedagogy (1) |

Pedagogy (1) |

Medicine (1) |

|

Engineering (1) |

Medicine (2) |

Nursing (1) |

Pedagogy (1) |

|

Law (1) |

|

Law (1) |

Law (1) |

|

Type of contract |

Part-time teachers (3) |

Part-time teachers (2) |

Part-time teachers (3) |

Part-time teachers (3) |

Full contract (1) |

Full contract (2) |

Full contract (1) |

Full contract (1) |

|

Gender |

Male (2) |

Male (3) |

Male (2) |

Male (2) |

Female (2) |

Female (1) |

Female (2) |

Female (2) |

To have a close conversation with the interviewees, we collected the data through semi-structured interviews (Kvale, 2011). The interview was organised in analytical categories that order information conceptually. Those groupings reveal the subcategories by which questions were asked to obtain the necessary information, such as the importance given to certain educational activities, the conception of the teachers’ role, and their perception of first-year students.

Semantic structural analysis (SSA) was chosen to analyse the corpus (Martinic, 2006, 2016) because it seeks to uncover the meaning prior to the construction of a narrative; it also described and built the structure that organised the text unit. It helped us understand the representations through which scholars define their context and identity and build a comprehensive model to understand first-year university students in the new social context of higher education massification; in doing so, they also represent themselves as professors in this new setting.

The SSA theoretical background is found in Greimas (1987) structural semantics. From its perspective, the deep structure analysis of a text aims to identify the norms and values that underlie said text. Different narrative structures can be based on a common deep structure. The components of this deep structure must be, first, sufficiently complex to be logically consistent and stable enough to provide an adequate representation of the text. Secondly, the analysis must fulfil its mediating and objectifying function between text and analyst; likewise, it must be precise enough.

Martinic (2006) suggested that in the first step, the basic meaning units and their relations with each other must be identified; in the second phase, the revitalization of the structure emerges from core categories. This step consists of the distribution of associations and oppositions identified in the action model; it allows for an analysis of the symbolic functions while assuming the various elements considered in the first step. These relations are expressed in structures that could be parallel, hierarchical, or crossed.

Crossed structures are the most complex ones and express the majority of the relationships among the codes in a representation framework. They happen when axial codes can have both positive and negatives meanings; by crossing two of them, four semantic fields emerge, allowing for distinguished nuances and ambivalences inside a representation (Martinic, 1992, 2006)

The main findings are organised into three categories that describe teachers’ representations of first-year students students’ commitment to learning in the context of the massification of CHE. An emerging category is representations of changes in academic work by teaching undergraduate students in the context of the massification of CHE. The first one describes the variety of students: their cultural capital, their quality, and their changes over time. The second category addressed the curriculum and its value to students’ education; finally, the third category describes the nature of faculty workload as related to the changes in scholarly life due to the arrival of a new type of student.

From the faculty perspective, students are divided into three semantics axes, which emerged from the interview discourse:

These axes are organised around the first-year students possession of hegemonic cultural capital. This representation helps faculty understand learning difficulties based on social origin and trajectories. This is shown in the following selected texts when respondents were asked the following question: What explains commitment toward learning among first-year students? [Interviewees are identified by department, type of contract, gender, and type of university, according to the established acronyms found in Table 1.]

‘Obviously is mainly due to their past schooling. For example, the guys from Saint Martín or British School (both private school) arrives at the university knowing the basis about how to learn, but at the same time, we receive country boys that can hardly express themselves properly. Even fewer can read a text of our domain’ [Ped, PT, M. SSPU]

‘I doubt they have ever taken a book for pleasure, they have spent their childhood watching TV […] it shows in the poor way they express themselves. They must be taught how to speak properly!’ [L, PT, F. PU]

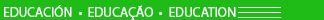

The first idea is about students that learn with little or no effort, meaning those who come from private schools, from a middle-class setting and with the possession of hegemonic cultural capital, as shown in the following parallel semantic structures organised around the semantic axis of ‘possession of academic capital’. It is important to note that middle class is defined by faculty perception, which might not coincide with a traditional middle-class schooling. In this case, the axis disjunctions are as follows: with/without hegemonic cultural capital, read/watch TV; private/public schools, and learn effortlessly/learn with effort (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Students’ possession of academic capital

Possession of academic capital is not expressed as such but is described as a list of academic qualities seen as intrinsic characteristics of the mentioned students. On the contrary, the lack of these scholarly attributes is explained as part of being low-class students coming from public schools. Students who lack these scholarly traits have to invest much effort in learning, whereas the students coming from middle-class backgrounds learned with no effort. The possession or lack of hegemonic cultural capital is not used as a way to question meritocracy in undergraduate studies or as a critical perspective on teaching strategies; is more an explanation that borders an essentialist view that puts all the responsibility for academic failure into class issues:

‘Private schools students leave to study at Santiago [capital city], the left over, are studying here in the city’ [Psy, PT, F, SSPU]

In line with that analysis, faculty described good students as capable of thinking (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Students quality

When they are asked to detail what they understand by a student who thinks, thinking becomes associated with being knowledgeable—again, possessing scholar cultural capital—and having soft skills, such as being responsible and proactive in classes. Bad students, on the contrary, are represented not as people who think in dubious ways but ones who are incapable of thinking of the most classic tabula rasa theory. For these professors, low-class students are bad students with little or no knowledge. Being a bad student also means being passive toward the acquisition of more knowledge. It is important to point out that there is certain social essentialism in these representations in which good and bad students are constructed. Following faculty discourse, student quality is mostly explained trough social origin, categories that turn out to be personal attributes, and attitudes toward learning.

‘Well, there are a few that interested in learning. Those are the few who read, who seek answers, which use the library willingly. Those are the students capable of thinking and make interesting connections between the discipline and their life. Most don’t do that; they are content reading your PowerPoint slides’ [Nur, PT, F, PU]

‘I think the determination is central: Being willing to learn. Many young people come with no interest in working: they don’t even ask questions during classes!’ [Eng, FC, M, SOU]

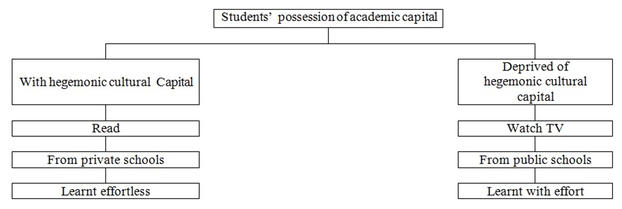

When asked, How would you describe your first-year students’ commitment to learning? professors not only pointed to class issues as a comprehensive unit but also organised their discourse around a narrative that is structured in the semantic temporal axis organised around the pairing of past and present (see figure 3).

Figure 3

Students through time

These categories explain the type of students through the ages as crucial to understanding the actual scenario: Past is signifies a past situation of CHE that was exclusive, open only to some few selected students. Present describes different circumstances in which higher education has a wider population, in which its massiveness is the main characteristic.

‘Students never come to my office unless they really are at risk of failing. When I was a student we work harder; we knew why we were there; now they expected to be spoon fed by faculty’ [Med, PT, F, SSPU]

‘In my time, only good students gained access to higher studies. We were a selected group of people interested in learning. We didn’t waste time. We had a social responsibility within our studies. We didn´t studied to make money but to serve the country. Kids today do not even know what they are studying for; sometimes I felt they are here to buy an academic title’ [L, PT, M, SO]

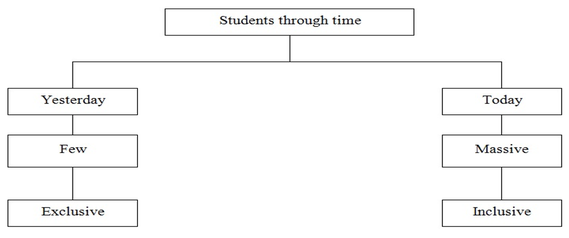

The aforementioned semantic axes are presented in an explicative crossed diagram (see Fig. 4).

Figure 4

Type of students through time.

When combining both axes, students through time and student quality, a more complex typology of students emerges, which can be understood as if a historical perspective was added (Fig. 4), the latter will be pointed in a binominal way: as ‘past/present’

To understand this crossed diagram, we have the student quality binomial (Fig. 4: A+A-) and the academic capital one (Fig. 4: B+B-). Four squares will emerge from this axis with one typology each. Such typology is dynamic through time, going from far away in the past, where higher education was completely exclusive to present times, organised through the idea of the massiveness of enrollment.

Following bourdesian categories, the past is organised between two types of students: Inheritors, who are in possession of scholarly, financial, and social capital (Fig. 4: Axis A+ B-), and scholarship-awarded students, who are the exception that confirm the rule: students who, even lacking this social and financial capital, were good enough to receive scholarships that allow them to reach higher education (Fig. 4: Axis A+ B+). In the minds of the professors, all those students had the inner qualities that identify them as good students, even if the most desirable one were the ‘all-rounders’, those who challenge their lack of academic capital by being good students.

As time passes, and we are nearer to the present, a new typology of students emerges: This typology is constructed around the bad student axis. Here, we find Clients (Fig. 4: A+A-) and Daddy darlings (Fig. 4: A-A-). The latter are bad students with financial support and social capital. They are seen as spoiled kids that make no effort to learn. The former group—clients—are bad students lacking scholarly capital, well aware of their rights, but not as much aware of their duties. Professors literally described them as having a client attitude toward academic work.

Professors were asked the following question: How should first-year students be taught? The discourse divided faculty into two groups: the ones that are learner centred as opposed to content centred. Learner-centered faculty members have an overall and articulated view of the curriculum and understand the purpose of the graduate profile and their contribution to it. These faculty members are part of an academic program that collaborates among different subject matters.

‘Teaching should be organised as a string. Each course is a link that relates to the next. Thus, students are acquiring the skills to become a professional. From the first year, you have to contextualise content to the profession they are studying’ [L, FC, M, PU]

In opposition to that idea, faculty discourse points out those academic service units, especially the ones that offer Basic Sciences to the academic programs—such as math, physics, chemistry, and anatomy—tend to be represented as content centred with no regard to the students’ learning process. As such, basic sciences faculty are seen as tending to forget their contribution toward the graduate profile by trying to teach unnecessary content.

‘Basic Sciences professors are cows. They aim to teach everything as if the purpose were to doctorate students. They don’t consider the context in which students will develop their professional work. How else can you explain that more than 80% [of students] fail anatomy class’ [Obs, FC, F, P.U]

At this point, it is important to remember that professors who participated in this study were all members of an academic program as opposed to members of service units (basic sciences department, generic courses, or remedial programs).

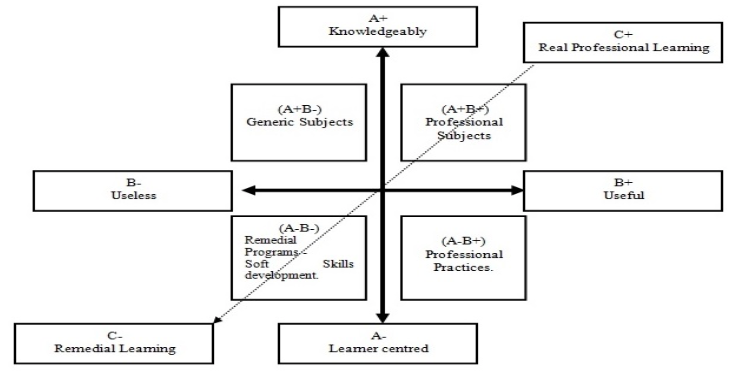

Not only are faculty represented as content or learning-centered, but types of courses are also organised around the axis of their utility. Here, the approach is totally pragmatic: Generic courses focused on giving students a wider comprehension of society and a broader focus on general culture, soft skills, or remedial lessons are seen as useless and as using too much time of a student’s academic workload.

‘Today is fashionable to fill the curriculum with idiot courses: [like] “personal development” and such. Stuff that have little to do with engineering’. [E, FC, M, SSPU]

Figure 5

Subject matter value

The curriculum value is represented in Figure 5. A course typology emerges in which ‘real professional learning’ (C+) is the main focus. This typology defines useful courses as mainly theoretical that tend to be content centred. Following these useful courses, it is possible to find ones that lend better to application, such as professional practices (Fig. 5:A-B+).

Among the perceived useless courses, professors describe generic ones and remedial programs (Fig. 5:A+B-). Courses centred on developing soft skills also are visualised as remedial. This typology is consistent with a traditional view of higher education in which theoretical courses are more valuable than applied ones. An education for the elite need not worry about developing soft skills or giving the students a broader culture because those are part of an incoming profile that should be reached before starting university. That is the same explanation for why remedial actions are despised because they threaten the meritocratic illusion by interfering with selection. This is a fact that tends to be stressed with more force by scholars who teach at state-owned and state-subsidized private universities.

The nature of academic work was an emergent category; mostly all the professors—with little care of their contractual category—organise their discourse along the ‘true nature’ of academic work, with that being defined as research activities. On the contrary, teaching in undergraduate courses is visualised as a by-product of academic life, a sort of unavoidable toll that needs to be paid in order to—eventually—being able to focus on research. Sometimes, this toll is a burden that wears out faculty instead of energising them to focus on the real work. Speaking in terms of first-year students, it is partially a way of describing academic life and its liabilities.

An important part of the burden described is that it is due to what faculty states as bureaucratization of teaching at undergraduate levels. The requirements for teaching first-year students are constructed as a symbolic enemy of true scholarly life. This is expressed in the binominal Academic/non-academic work. For the interviewees, academic work is a matter of honour and dignity; it means academic freedom, autonomy, and the institutional recognition of faculty worth among society.

Academic work involves teaching tasks that promote students’ learning; as such, it is a profitable work that is seen as scarce if compared to bureaucratic workload of non-academic issues. This is an interesting point. Even if teachers resent changes in higher education first-year students, they can value, at some point, the necessity to focus on their learning, but they distance themselves from manager initiatives.

Bureaucratic workload or non-academic issues are described as a nonsensical activity that is more focused on controlling aspects of teachers’ duties than being focused on improving learning. From their view, the problem here is that such tasks are not only insulting but also are distracting faculty from the real aim of teaching.

Figure 6

Nature of faculty workload associated to teaching through times

The representations about the nature of faculty workload associated with teaching over times (Fig.6) give us an interesting insight into the problematization of teaching first-year students. Faculty mourn a past golden age (Fig. 6: C+) of undergraduate teaching (Fig. 6: axis A+B+) in which there was previously academic freedom and excellent students. It is impossible for them to imagine a past in which academic work involved loads teaching to paperwork. (Fig. 6: axis A-B+).

This is opposed to the present (Fig. 6: A-B-), in which any pedagogical action required by university authorities is viewed as a degradation of their work and is understand as lowering the theaching standards and cuddling students. This is consistent with the idea of a good student, for which social and inner trades explain success over teachers’ actions:

‘It’s this patronizing attitude towards the student body that irks me, as we are expected to quit higher expectations, in order to help them’ [Psy, FC, F, PU]

In faculty discourse, academic freedom is also falling down the slope as a result of new management policies that understand little of the true nature of academic work and reduce academic life to paperwork. When asked about what kind of paperwork that was, a wide spectrum of responses was offered. Scholars from state-owned and state-subsided private universities emphasised the needs of planning classes and using different assessing instruments. Whereas scholars from private universities mentioned specific mandatory acts, such as filling out institutional forms, calling the roll, and other practices that are recognised as similar to the ones made by high school teachers, thus threatening their identity as academics and seen as insulting.

In this communication, our purpose was to investigate what representations of first-year students learning commitment are sustained by professors in the context of the massification of Chilean higher education. This is relevant as students from a variety of context arrive at university for the first time in our history. The results support the characterization of actual first-year students as diminished and unfit to undergraduate studies, which tends to be a burden to scholars. An idea most vividly appreciated is the use of adjectives to describe them, such as ignorant, irresponsible, and slackers. It also shows both a lack of understanding of sociocultural variables involved in learning and the existence of classism to explain academic success or failure. While one might argue that there are teachers who address students’ needs, while implied in the above complaint against anatomy classes, the fact remains that most of the discourse is organised around the idea of a declining quality of the student body—either because they are spoiled or because they have a consumerist attitude toward learning. Concha (2009) accounted for how first-generation Chilean students refer to the classist treatment scholars give them, which is linked to a bad disposition toward teaching them. Our interviewees appear to hold this approach.

The act of teaching is seen, by these professors, as an intellectual gift to the naturally gifted. In this perspective, academic success or failure is explained with categories that are external to teaching itself, such as class—only in the cases that explain failure—or intelligence when they are explaining success. In a more massive scenario, professors felt their identity was threatened by what they saw as a refusal to receive their donation: lack of effort or what is perceived as an unfair claim over the students’ rights in what they recognised as a client attitude towards study. Arguments concerning the need to address these representations are supported as scholars’ expectations on their students affect their learning (Zhou, 2013)

Thus, a first representation is one of the students as an input for sound teaching. In this perspective, the faculty efforts are successful while having a good student who can appreciate the ‘gift’ given by the teacher: their expert knowledge. This makes it difficult to advance toward a learning centre process insofar as the academic success of students is explained from categories that reify learners. For our first-year students, this is crucial since poor instruction proved to be a major variable on first-year students drop-out rates (Black, 2015; Bosse, 2015; Donoso & Schiefelbein, 2007; Gale, Ooms, Newcombe, & Marks-Maran, 2015) since their social capital is what mainly explained their failure or success (Donoso & Schiefelbein, 2007).

Our second representation about first-year students’ commitment toward learning is conditioned to curriculum redesign in four universities; which is grounded on the need to ‘cuddle students instead of teaching them rigour’ [Eng, FC, M, SOU]. Sometimes, this representation is tinged with the need to address students’ adaptation to academic life and professional outcome; still, the tendency is to value a discipline-oriented curriculum narrowed between the confines of the profession. This explains how professional practices are valued over remedial and generic subjects. The need to open the curriculum to remedial activities or one that broadens students’ capital is part of the first-year student's representation: it is their fault—as damaged goods—that the curriculum has degenerated into its actual form. It is important to note that the sample only considered faculty from professional departments and excluded faculty from basic sciences and humanities that provided services to these programs that might have presented different approaches to curriculum.

The third social representation is about the nature of academic work. Students are visualised as one of the resources related to such a job. As such, discussing their students is deeply related to discussing their career conditions. Scholars rebel against the teaching supervisory mechanisms at universities and technocratic rationalities that support them stated under the form of a pedagogical discourse of instrumental nature. Our findings are partially consistent with Ek (2013) professors experiencing marketization and managerial practices as a threat that challenges academic autonomy.

There is an important frustration among faculty members due to what they perceive as difficult work due to changes in CHE; a task that has not had much formal development. This frustration sets an external locus of control toward the responsibility among students’ academic achievement. Further, this position blames the students for their failure, turning them into an input for teaching. This point is particularly interesting if we try to problematize a learning-centered environment due to the lack of recognition of students’ context and preconception as something valuable for their learning. Even if teachers acknowledge social differences, they tend to see them as static qualities that are an obstacle to academic success. Meritocracy is slippery here when inner and social attributes are confused to explain failure as a deterministic issue, signifying students as an object. Students are described as lacking the necessary knowledge and skills for academic, and this represents an overall degradation of the academic world. Consequently, it is not possible to discuss more student-centered approaches toward teaching without addressing their sociocultural settings and faculty working conditions.

It is yet to be seen in more advanced studies how these representations affect students’ academic achievements. An important point here is that there is little difference among faculty while describing first-year students, or in type of contract, gender, or type of university. A tendency toward more boldly discriminating commentaries came from health-related faculty as well as law and engineering school faculty.

Some interesting trends should be addressed; mostly they are centred representations that affect teachers’ change toward a more student-centered approach that could distance itself from the instrumental approaches of a market-oriented university.

Abric, J.-C. (2013). Prácticas sociales y representación. México: Editorial Coyoacan.

Atkinson, R., & Flint, J. (2001). Accessing hidden and hard-to-reach populations: Snowball research strategies. Social research update, 33(1), 1-4.

Black, T. S. (2015). Education students' first year experience on a regional university campus. University of Southern Queensland.

Bosse, E. (2015). Exploring the role of student diversity for the first-year experience. Enculturation and development of beginning students, 45.

Bourdieu, P. (1998). P. Os três estados do capital cultural. Magali de Castro (trad.) In.: NOGUEIRA, MA; CATANI, AM (Org.). Escritos de educação. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 71-79.

Brunner, J. J. (2011). Gobernanza universitaria: tipología, dinámicas y tendencias. Revista de educación(355), 137-159.

Caldwell, P. H. (2010). COLLEGE RETENTION: Support networks for first generation students of African descent. University of Illinois at Springfield.

Cancino, R. (2010). El Modelo Neoliberal y la Educación Universitaria en Latinoamérica. El caso de la universidad chilena. Sociedad y discurso, AAU(18), 152-167.

Carrell, S. E., Fullerton, R. L., & West, J. E. (2008). Does your cohort matter? Measuring peer effects in college achievement. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/600143

Castillo, J., Santiago, V., & Cabezas, G. (2010). La caracterización de jóvenes primera generación en educación superior. Nuevas trayectorias hacia la equidad educativa. Calidad en la Educación(32), 45.

CNED. (2011). Evolución de la matrícula de Educación Superior 1994–2011. Retrieved from Santiago, Chile: http://www.redetis.iipe.unesco.org/publicaciones/evolucion-de-la-matricula-de-educacion-superior-1994-2011/

CNED. (2015). Matrícula total de Educación Superior, años 2005-2015. from Consejo Nacional de Educación Superior http://www.cned.cl/public/Secciones/SeccionIndicesPostulantes/CNED_IndicesTableau_MatriculaSistema.html?IdRegistro=001

Concha, C. (2009). Sujetos rurales que por primera generación acceden a la universidad y su dinámica de movilidad social en la región del Maule. Calidad en la Educación(30), 121-158.

Donoso, S., Arias, Ó., Weason, M., & Frites, C. (2012). La oferta de educación superior de pregrado en Chile desde la perspectiva territorial: inequidades y asimetrías en el mercado. Calidad en la Educación(37), 99-127.

Donoso, S., & Schiefelbein, E. (2007). Análisis de los modelos explicativos de retención de estudiantes en la universidad: una visión desde la desigualdad social. Estudios pedagógicos (Valdivia), 33(1), 7-27.

Dumais, S. A., & Ward, A. (2010). Cultural capital and first-generation college success. Poetics, 38(3), 245-265.

Ek, A.-C., Ideland, M., Jönsson, S., & Malmberg, C. (2013). The tension between marketisation and academisation in higher education. Studies in Higher education, 38(9), 1305-1318.

Engle, J., & Tinto, V. (2010). Moving Beyond Access: College Success For Low-Income, First-Generation Students (The Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, 2008).

Espinoza Díaz, Ó., & González, L. E. (2012). Higher Education Policies in Chile from The Equity Perspective. Sociedad y Economía(22), 68-94.

Flick, U. (2015). El diseño de la investigación cualitativa.: Ediciones Morata.

Gale, J., Ooms, A., Newcombe, P., & Marks-Maran, D. (2015). Students' first year experience of a BSc (Hons) in nursing: A pilot study. Nurse education today, 35(1), 256-264.

Greimas, A. J. (1987). Semántica estructural: investigación metodológica: Editorial Gredos.

Kuh, G. D. (2008). Excerpt from High-Impact Educational Practices: What They Are, Who Has Access to Them, and Why They Matter. Assoc. of Am. Colleges and Univ., Washington, DC.

Kvale, S. (2011). Las entrevistas en investigación cualitativa: Ediciones Morata.

Lomi, A., Snijders, T. A., Steglich, C. E., & Torló, V. J. (2011). Why are some more peer than others? Evidence from a longitudinal study of social networks and individual academic performance. Social science research, 40(6), 1506-1520.

Lu, F. (2014). Testing peer effects among college students: evidence from an unusual admission policy change in China. Asia Pacific Education Review, 15(2), 257-270.

Marshall, J. (2010). Educación Superior: Institucionalidad para los nuevos desafíos. Calidad en la Educación(32), 235-251.

Martinez, J. A., Sher, K. J., Krull, J. L., & Wood, P. K. (2009). Blue-collar scholars?: Mediators and moderators of university attrition in first-generation college students. Journal of College Student Development, 50(1), 87.

Martinic, S. (1992). Análisis Estructural: presentación de un método para el estudio de lógicas culturales: Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo de la Educación.

Martinic, S. (2006). El estudio de las representaciones y el análisis estructural de discurso. Metodologías de investigación social. Introducción a los oficios, 299-319.

Martinic, S. (2016). Principios Culturales De La Demanda

Social Por Educación. Un Análisis Estructural. Pensamiento Educativo, Revista De Investigación Educacional Latinoamericana., 16(1), 313-340.

Matear, A. (2006). Barriers to equitable access: Higher education policy and practice in Chile since 1990. Higher Education Policy, 19(1), 31-49.

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis. A Methods Sourcebook 3 rd Edition: SAGE Publications.

OECD. (2013). Reviews of National Policies for Education: Quality Assurance in Higher Education in Chile 2013. Retrieved from /content/book/9789264190597-en http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264190597-en

Padgett, R. D., Johnson, M. P., & Pascarella, E. T. (2012). First-generation undergraduate students and the impacts of the first year of college: Additional evidence. Journal of College Student Development, 53(2), 243-266.

Rodríguez-Ponce, E., Gaete Feres, H., Pedraja-Rejas, L., & Araneda-Guirriman, C. (2015). Una aproximación a la clasificación de las universidades chilenas. Ingeniare. Revista chilena de ingeniería, 23(3), 328-340.

Santelices, M. V., Ugarte, J. J., Flotts, P., Radovic, D., & Kyllonen, P. (2011). Measurement of New Attributes for Chile's Admissions System to Higher Education. ETS Research Report Series, 2011(1), i-44.

Seifert, T. A., Pascarella, E. T., Wolniak, G. C., & Cruce, T. M. (2006). Impacts of good practices on cognitive development, learning orientations, and graduate degree plans during the first year of college. Journal of College Student Development, 47(4), 365-383.

Slachevsky, N. (2015). A neoliberal revolution: the educational policy in Chile since the military dictatorship. Educação e Pesquisa, 41(SPE), 1473-1486.

Stephens, N. M., Fryberg, S. A., Markus, H. R., Johnson, C. S., & Covarrubias, R. (2012). Unseen disadvantage: how American universities' focus on independence undermines the academic performance of first-generation college students. Journal of personality and social psychology, 102(6), 1178.

Stuber, J. M. (2011). Integrated, marginal, and resilient: race, class, and the diverse experiences of white first‐generation college students. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 24(1), 117-136.

Wiggins, J. (2011). Faculty and first‐generation college students: Bridging the classroom gap together. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2011(127), 1-4.

Zhou, Q.-f. (2013). The Application Of Pygmalion Effect In The English Teaching For The First Year University Students. Journal Of Tongren University, 15(3), 107 - 110.

This work was supported by the FONDECYT under Grant 1120351 2012; FONDECYT under Grant 11130035 2013; and by PMI UCM 1310.

1. Doctora en Ciencias de la Educación. Centro de Investigación en Educación para la Justicia Social. Universidad Católica del Maule. Talca – Chile. aprecht@ucm.cl

2. Doctor en Ciencias de la Educación. Centro de Investigación en Educación para la Justicia Social. Universidad Católica del Maule. Talca – Chile. ilichsp@gmail.com

3. Doctor en Ciencias de la Educación. Centro de Estudios Avanzados Universidad de Playa Ancha jorge.valenzuela@upla.cl

4. Doctora en Ciencias Psicológicas y de la Educación. Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaiso. carla.munoz@pucv.cl