Vol. 39 (Number 40) Year 2018. Page 28

Vol. 39 (Number 40) Year 2018. Page 28

Sagima SULTANBEKOVA 1; Assel KOSHEKOVA 2; Aigul BIZHKENOVA 3; Madina ANAFINOVA 4; Leilya SABITOVA 5

Received: 24/08/2018 • Approved: 28/08/2018

ABSTRACT: The purpose of this research is to define the modern processes of Kazakh word-formation and to highlight the most productive word-formative neologism types. A huge amount of information about word-formation in Kazakh is available now, but much less is known about Kazakh neologisms and the ways of their retrieving. The criteria of neologisms and modern word-formative trends remain an important unsettled issue. The tendencies of word-formative types can be changing due to the changes of technical, social and political sides of human life. |

RESUMEN: El objetivo de esta investigación es definir los procesos modernos de formación de palabras kazajas y resaltar los tipos más productivos de neologismo formativo de palabras. Actualmente se dispone de una gran cantidad de información sobre la formación de palabras en kazajo, pero se sabe mucho menos sobre los neologismos kazajos y las formas de recuperarlos. Los criterios de los neologismos y las modernas tendencias formativas de la palabra siguen siendo un problema importante y sin resolver. Las tendencias de los tipos formativos de palabras pueden estar cambiando debido a los cambios de los aspectos técnicos, sociales y políticos de la vida humana. |

Being first sketched in 1759 in France the issue of neologisms stays relevant up today. Maarten Janssen (2011) noted: “Neologisms form a highly relevant linguistic category for many reasons – they are the elements that make a language living and dynamic rather than dead, they are indicative of language change…” There are so many trivial issues concerning neologisms starting with definition of neologisms, the matter of novelty, their identification tokens, principles on selecting them for a lexicographic work and so on. Since it is not possible to cover all these questions in one paper, the authors aimed to consider word-building tendencies of Kazakh neologisms in “Egemen Kazakhstan” newspaper and “Azattyq news” platform. In order to identify the neologisms in the corpus we have to outline the definition of neologisms and the matter of novelty as the most important concerns.

The current paper deals with following research questions: How can the whole nature of neologisms be revealed? Are the Kazakh neologisms actual nowadays and what historical background do they have? What are the ways to extract neologisms from a corpus? What is the tendency in building Kazakh new words?

When we examined the definitions of a neologism that are suggested by Kazakh scientists and in dictionaries, then we made sure that they are limited within one or two sentences without explanation:

Among the considered attempts to give a definition to neologism the approaches of Russian scientist N. Kotelova (1998) and French scientist A. Rey (1995) seemed the most suitable. To supply the appropriate definition of neologism Kotelova considers focusing first on parameters of concretization. As parameters for concretizing the neologisms she outlines four important aspects:

Alain Rey admits that the concept of neologism should be applied to combined structures lying between the morpheme and the phrase. He writes: “I have defined a neologism as: “a lexical unit perceived as recent by language users’ which reduces the idea of novelty to psychological and social factor which is therefore no longer objective and chronological’… For all immediate and practical purposes, neologisms can be considered as new units in a specific linguistic code. This apparently clear and coherent concept faces us with three questions:

The scholar explains the novelty in neologisms connected to types of neology (formal, semantic and pragmatic). He highlights the rise of formal novelty from discourse, from active language through the complex expression. According to him, formal neology is a kind of neology where one can apply grammar rules in the morphemic structure of the language. Semantic feature of neology is typical to all kinds of neologisms and semantic novelty is total in the system (case of borrowings), partial (creations by affixation, composition, agglutination into complex words or syntagmatic formations into word groups) or very weak (the case of acronyms and abbreviations, because they only express the meanings of the form they abridge…). Rey links the pragmatic neology with communication. He sees the pragmatic novelty in settings of formal and semantic novelty.

These two approaches suggest that the definitions of neologisms should be always considered in parallel with answering to a line of questions. Both scholars focus more on factors of neologisms that would lead to defining neologisms as properly, rather than the definition itself.

Taking into account the above-mentioned two ways we will try to summarize them in Table 1 that would assist us in identifying and retrieving neologisms of the Kazakh language as one branch of Turkic group of languages:

Table 1

Criteria for neologisms (different approaches)

Criterial Questions for Identifying neologisms |

When? (Kotelova’s approach)

|

Where? (Kotelova’s approach)

|

What is new? (both Kotelova’s and Rey’s approaches)

|

Which structural features are new? (both Kotelova’s and Rey’s approaches) |

Kind of linguistic unit |

||||

A word or combination |

time of first appearance and frequency (Richards: Word List) |

kinds of texts: coverage (Richards: Word List) |

the form or meaning |

novelty in structural forms |

A morpheme |

||||

A lexeme |

||||

A phraseological expression |

To outline the word-building tendencies of Kazakh neologisms it is necessary to analyze the latest trends of identification and retrieving neologisms from a text or corpus in the world. The analyses are drawn as the following.

Pontus Stenetorp’s Master Thesis (2010) presents the detailed analysis and attracts the users of the language in the process of extracting the neologisms. The authors believe the users' attraction to be the right solution as for the start just machine extraction of neologisms seems to be a bit not complicated work in such an important issue concerning neologisms.

For extracting the neologisms the authors first started with constructing temporally annotated corpus from texts selection of blogs. In this temporally annotated corpus they updated the newspaper and blog texts processing. The texts were left with titles and bodies being considered important for the succeeding work. After collecting a large set of data the system itself was constructed. This system was differentiated with absence of filtering the potential neologisms. The authors proceeded from Janssen’s work (2011), where Janssen noted that any filtering could bear a risk not choosing a potential neologism. Instead of filtering they considered all the potential words and gave rates to potential neologisms. After such words were collected, they trained the data and the proposals to the users. Instead of lexicographers they attract the users' answers if they think of a potential word as new or not. After their feedback the words were scored again.

This new classifier will be improved in future.

Piotr Paryzek (2009) supplies valuable information, comparing the most interesting to us “the retrieval of phrases method”, and “morphological analyzer method”.

Then he collects articles from newspapers: “Editorials, Research Highlights, News, News Features, Correspondence, News and Views, Brief Communications, Articles and Letters” and a scientific journal “Nature” for 1997-2005.

As in the previous case all the Internet texts are processed and compiled into a large file. He practices retrieval phrases (– termed, – called (which includes so (-) called), – known as, – defined as) and punctuation discriminate approach, morphologic analyzer and then separates the rarest units, too. After he suggests analyzing the word lists manually. Here he highlights the importance of a linguist’s assistance in getting the final result.

Another approach by Maarten Janssen (2011) is based on the web-based tool called Neo-Track. Neo-Track differs from the previous approaches in inclusion of the “exclusion list” in the process of retrieving neologisms. In this list all non-neologisms are considered. According to the Neo-track process, all the corpus texts are scrutinized in their original formats, and then they are accrued, after being symbolized for a list of neologisms. According to Neo-track, final result is achieved manually giving a chance for those words from the exclusion list to be put to the final result list of neologisms in case they have true clues for being a neologism.

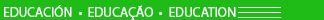

Having studied all these approaches the authors attempted to construct their own detection method (Figure 5) for Kazakh neologisms combining the appropriate stages from the above-discussed approaches. This is shown in the following scheme:

Figure 1

The method of retrieving new words from a newspaper

Investigations about new words take roots from word-building theories. Kazakh scholar N. Oralbay (2007) notes although word-building of the Kazakh language is taught as a separate discipline just from the middle of the 90-s, previously it was considered as part of morphology. In the framework of morphology only word-building of parts of speech was analyzed. Highlighting the impossibility of explaining all the details of Kazakh word-building within morphology, N. Oralbay first worked out a program of Kazakh word-building in 1992. According to this program, Kazakh word-building originates from the Turkish language. Derivatives from the ancient written manuscripts are good proofs for that. Those derivatives show that synthetic (saualnama – questionnaire), analytical (sirke suy – vinegar), and semantic ways (zholnuskha – guidance) of word-building were popular then, too. The semantic method is prominent in creating compositions. The data of this paper will start with analyzing compositions that are made by the semantic method, affixations that are made in the synthetic way and abbreviations that are made on their own.

It is a fact that new words and new concepts appear in the language through the entire history of the language despite the period of emergence of word-building as a separate discipline. It would be fair to speak about neologisms according to their periods as a new word of one period is not new in the subsequent period. When it comes to periods of Kazakh neologisms, Kazakh outstanding scientist Rabiga Syzdyk (2009) highlights the following periodization of neologisms that can be proven with factual examples:

- Second half of the XIX century. New words appeared in this period due to such social factors, as: printing industry, eagerness to get education, flourishing of Muslim religion; e.g.: sailau (voting); nesie (credit); ma’sele kitap (paper-based intellectual propaganda);

- Fist decades of the XX century are noted as a distinguished period of neologisms as the result of distinctive development of the previous social factors; e.g.: new terms suggested by Kazakh outstanding enlightener, scholarly linguist Akhmet Baitursunuly: zat esim (noun); syn esim (adjective); san esim(numeral); bastauysh (subject); bayandauysh (predicate), etc.;

- The 1920-1930-s: this period is noted for a great amount of neologisms as the Kazakh society started to live in the Socialist system. e.g.: tonkeris (revolution); tendik (equality); okil (representative);

- The 1940-1950s: new words appeared due to technical development, military structure and weaponry during the World War II. e.g.: zhayunger (soldier); kharakhagaz (a letter telling about death of a soldier);

- The 1970-s. Development of aerospace and world scientific-technical news caused the appearance of new words in the Kazakh language. But there was a tendency during this period to use ready words of the Russian language, whose influence was very crucial on Kazakh. These Russian words were used without alternatives in Kazakh: e.g.: ostanovka (bus stop), morozhenoe (ice-cream), dacha (country house);

The date of the first period (2nd half of XIX century) of Kazakh neologisms does not mean that it lacked new words previously, it is true that a language witnesses new words at all its stages, but neologisms before the 1st period are very limited and in fact they are not preserved.

The 6th period – flourishing period of Kazakh neologisms comes back to the Independent Period of Kazakhstan, i.e. from the 1990s up to now. That is the reason why we are interested in revealing word-building tendencies of Kazakh neologisms.

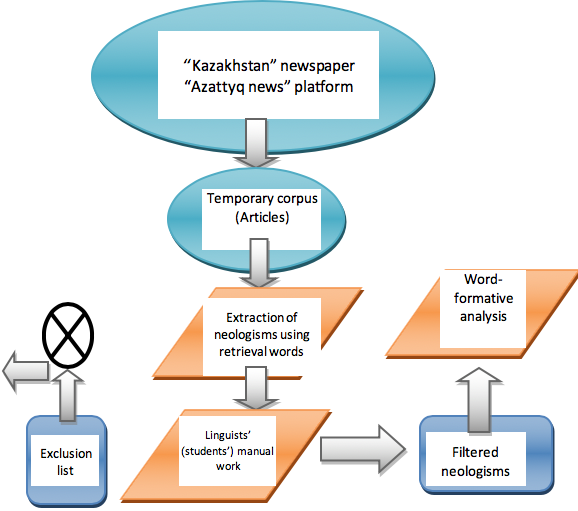

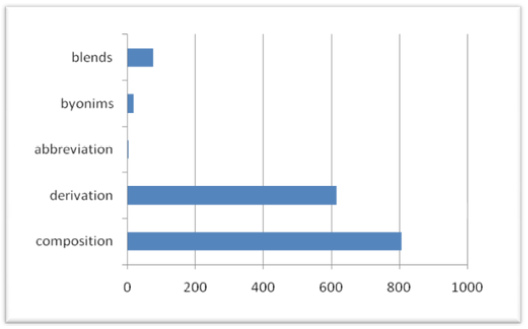

The authors have analyzed articles from the Kazakhstani “Egemen Kazakakhstan” newspaper and “Azattyq news” platform over the last 12 months. Among the actual word-formative types in Kazakh composition, affixation and abbreviation can be defined (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Word-formative types in the Kazakh language

One of the popular types of word-formation in Kazakh is suffixal derivation, as far as Kazakh is defined by strict sequence of adding suffixes to the root. This derivational type of forming new words is of special respect, in different periods of time the functions of definite suffixes were increasing, and some of them occurred very rarely. Suffixes impart to the word the special meaning, for example the suffix –хана is used for creating words with meaning of compartment (places).

Suffix –хана: quralkhana [құралхана] (workshop), qasapkhana [қасапхана] (slaughterhouse), putkhana [пұтхана] (temple), sauyqhana [сауықхана] (casino), shatkhana [шатхана] (café), gharyshkhana [ғарышхана] (spaceport), dumankhana [думанхана] (restaurant), qoqyskhana [қоқысхана] (junkyard), qumarkhana [құмархана] (casino), meimankhana [мейманхана] (hotel), tabytkhana [табытхана] (entombment).

Next group of suffixes in the Kazakh language forms the nouns with the meaning of instrument of action. Suffix –гіш/ғыш/қыш/кіш: bo’lingish [бөлінгіш] (divisible), belsendirgish [белсендіргіш], ko’tergish [көтергіш] (crane), ten’gerish [теңгергіш] (equalizer), zhiktegish [жіктегіш], magnito’tkizgish [магнитөткізгіш] (magnet conductor), aua o’tkizgish [ауа өткізгіш] (air conductor), avtotu’sirgish [автотүсіргіш] (autotruck), sujinaghysh [сужинағыш] (water collector), syzghysh [сызғыш] (ruler), joyghysh [жойғыш] (chaser), avtoqu’ighysh [автоқұйғыш] (autofunnel), avtojanarmaiqy’g’ysh [автожанармайқұйғыш] (auto gas pistol), jetkigish [жеткігіш], hoshiistendrgish [хошиістендргіш] (aromatization), qy’laqkiigish [құлақкигіш] (earphones).

Suffixes –гер/кер, -шы/ші are added to the nouns and serve for determining professions, duties and some types of actions.

Suffix –гер/-кер: alauger [алаугер], a’kimger [әкімгер] (administrator), baspager [баспагер] (publisher), qiyalger [қиялгер] (dreamer), sahnager [сахнагер] (performer), tu’zetker [түзеткер] (leveler).

Suffix –шы/ші: aitaqshy [айтақшы], ayaqdopshy [аяқдопшы] (football player), a’rleushi [әрлеуші] (grinder), bezenshi [безенші] (decorator), demeushi [демеуші] (sponsor), ma’ndiso’zshi [мәндісөзші] (orator), salymshy [салымшы] (investor), saparshy [сапаршы] (tourist), syrg’anaqshy [сырғанақшы] (figure skater), an’yqtamashy [аңықтамашы] (receptionist).

With the help of suffixes –лік/лық, дік/дық, тік/тық abstract nouns are formed from adjectives: o’timdilik [өтімділік] (profitability), belsendilik [белсенділік] (activity), ystyqqato’zimdilik [ыстыққатөзімділік] (high-temperature strength), yrystylyq [ырыстылық] (luckiness), eselilik [еселілік] (productiveness), bastamashyldyq [бастамашылдық] (initiation), beibitsu’gishtik [бейбiтсүйгіштік] (peacefulness), birtektilik [біртектілік] (monotony), deneushilik [денеушілік] (sponsorship), elzhandylyq [елжандылық] (patriotism), ko’shbashylyq [көшбасшылық] (leadership), qazirgilik [қазіргілік] (modernity), qoljetimdik [қолжетімдік] (availability), sanatkerlik [санаткерлік] (respectiveness), sodyrlyq [содырлық] (mischief).

In modern terminological dictionaries, words with the prefix –бей (bei) are quite often encountered, as a separate element in the composition of the word, since the following neologisms were formed, in what follows terms: beipartiyalyq [бейпартиялық] (non-party), beisayacatshylyq [бейсаясатшылдық] (non-politicism), beiazamattyq [бейазаматтық] (non-citizenship), beiresmi [бейресми] (non-official).

Compounding (formation of composites) in the Kazakh language is a very productive way of word formation, in contrast to affixation, where only one component has an independent meaning, while others perform a functional role, compound words are formed by adding two significant words and represent a lexically unified item expressing one concept. Composite word formation in the Kazakh language is also an actual trend. Composites can be determinative and copulative.

Determinative composites: aqyrso’z [ақырсөз], aspanserik [аспансерік] (stewardess), a’ua’serik [әуәсерік] (air hostess)], a’tirsabym [әтірсабын] (shower gel), belgitaqta [белгітақта] (smart-board), g’u’myrbayan [ғұмырбаян] (biopic), jolserik [жолсерік] (hostess), жолдорба [joldorba] (backpack), a’lemtor [әлемтор] (Internet), g’alamtor [ғаламтор] (internet), ba’ssauda [бәссауда] (auction).

- Сөз (so’z): alqaso’z [алқасөз] (introduction), balamaso’z [баламасөз] (equivalent), kirisso’z [кіріссөз] (introduction), qainarso’z [қайнарсөз] (reference), qog’amso’z [қоғамсөз] (public speech), ma’ndiso’z [мәндісөз] (speech), sharshyso’z [шаршысөз] (square speech)

- хат ((k)hat): Tapsyryskhat [Тапсырысхат] (task letter), lebizkhat [лебізхат] (acclaiming list), mu’rakhat [мұрахат] (testament), qu’zyrkhat [құзырхат] (competence list), ashyqhat [ашықхат] (official letter).

Copulative composites:

ai’darbelgi [айдарбелгі], ayaqdop [аяқдоп] (football), a’ua’dop [әуәдоп] (volleyball), zymyrantysyg’ysh [зымырантысығыш] (pump), qu’qyqbu’zyshylyq [құқықбұзышылық] (opposition), qu’ltemir [құлтемір] (robot)

Byonims, complex words with hyphened spelling, are a characteristic feature of the Kazakh language. In the formation of lexical innovations in the Kazakh language, byonims (or pairs of words) are rare; however, there are patterns of formations and a variety of structural features. Pair units are formed from words of the same type, which are the same in a grammatical sense, i.e. from words of the same part of speech.

Byonims (two words combined into one get a new meaning): ayaq-tabaq [аяқ-табақ] (tableware), aryz-tilek [арыз-тілек] (good wish), bet-beine [бет-бейне] (face to face), o’lim-jetim [өлім-жетім] (orphan kids), qor-qor [қор-қор] (store), ar-abyroi [ар-абырой] (responsibility), syi-ka’de [сый-кәде] (gift), syn-qater [сын-қатер] (challenge), pisip-jetily’ [пісіп-жетілу] (maturity), da’ri-da’rmek [дәрі-дәрмек] (medicine).

Balakayev (2007) proposes to relegate phrases to compound words: "Phrases as a semantic syntactic group of words is the main basis for the formation of complex words" and contact words (the Balakayev's term), that is, words with full meaning that come into contact according to semantic syntactic connection and form new words with new integral lexical meanings. Balakayev speaks about the tendency of the complex formulation of complex words in the practice of the literary language and the fact that journalists consciously develop and encourage uniformity of terms and other words as a practice of rational form and way of designating a single concept. For example: elbasy [елбасы] (Head of the nation), elorda [елорда] (capital), u’ltjandylyq [ұлтжандылық] (national awareness), a’skerbasy [әскербасы] (head of the martial troops), u’ltaralyq [ұлтаралық] (transnational), tiku’shaq [тікұшақ] (helicopter) (Isaev and Nurkina 1996).

Recently, in connection with the appearance of the Internet and the active use of social networks, word-formative products formed as a result of contamination have appeared, until a certain time this word-building method was not so productive.

Contamination in the Kazakh language: қыстана [қыс+Астана] (winter+Astana), өлфи [өлу+селфи] (die+selfi), мамамдық [мамам+мамандық] (mom+profession), қост айту [тост айту+қосу] (wish+add), жексі көру [жақсы көру+жек көру] (love+hate), өзденіс [өз+іздену] (self+search), қырпоп [қырғыз+поп] (Kyrgyz+pop), доспан [дос+дұшпан] (friend+enemy), досхаббат (дос+махаббат) (friend+love).

Hybrid words and word formation as a result of close language contacts are one of the signs of the modern policy of the Kazakh language borrowings. During the Soviet period, the Russian language was a model for the Kazakh language, on this basis foreign vocabulary was introduced. Semantics, pronunciation and spelling were standardized, thus the influence of the Russian language became unlimited. The process of transferring foreign vocabulary into the Kazakh language occurred purposefully through the Russian language.

With the acquisition of Kazakhstan's independence and gradual integration into the world's economic, political, cultural and educational space, the Kazakh language has become an active recipient of foreign vocabulary. However, today there is a tendency for a purposeful departure from the use of borrowings (that have come mostly from the Russian language or combining the signs of the Russian language).

The terminological resources of the Kazakh language were also severely regulated; many words of international origin were replaced by the equivalents of the Kazakh language (airport– әуежай, space – ғарыш, the Internet– әлемтор, ғаламтор).

Nevertheless, there are areas of social life remaining in which the influence of the Russian language still determines the characteristics of the borrowed vocabulary. For example, the lexical layer produced by technogenic process waves (the Internet and social networks, information technologies and mobile communication), where the word-formative and nominative potencies of the Kazakh language are influenced not only by the English language, but, to a large extent, by the Russian language. On the other hand, foreign vocabulary, reflecting cross-cultural concepts in the spheres of sports, music, art, fashion, youth movements and gastronomic novelties, retains signs of foreign influence.

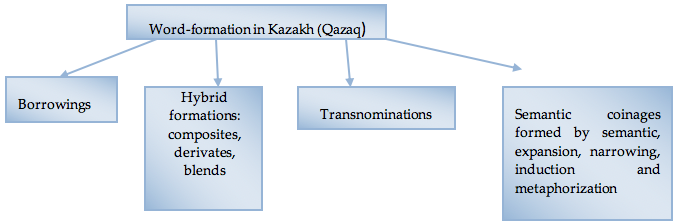

These factors are prerequisites for the emergence of hybrid formations in the Kazakh language. Hybrid word formation is a modern trend in modern languages and it is divided into two main groups: hybrid composites and hybrid derivatives (see Figure 3).

Compositional word formation:

External lexeme + internal lexeme: газқұбыр (gas pipe) , кинокеңестік (cinema space), киножоба (cinema project), медиабедел (media respect), медиазорлық (media health), киноөндіріс (media production), агроқұрылым (agro construction), агроөнерксіп (agribusiness), агросала (farming industry), агросаясат (farming policy), биоотын (biofuel), биотолқұжат (bio passport), биосүзгі (bio filter), Еурожөндеу (European-style remodeling), Еуроаймақ (Eurodistrict), дендробақ(dendro park), конусбейнелі (in the shape of conus).

Figure 3

Hybrid formations in Kazakh (Qazaq)

Internal lexeme + external lexeme: бейнеклип (video clip), бейнеконференция (video conference), бейнесюжет (video plot)

Derivative word formation:

External prefix + internal lexeme: наноқор (nano store), мегажоба (mega project), супертек (super origin), супермұқаба (super cover), трансұлттық (transnational), трансқұрылықтық (transcontinental), фотокөрме (photocopy), фотокөрініс (photo exposition), фотоқондырғы (photo rack), фототілші (photo correspondent), телехикая (TV program), телекөпір (TV connection), телекөрермен (TV audience), телемұнара (TV tower), телеойын (TV game), киберқауіпсіздік (cybersafety), киберқарашы (cyber service), киберқылмыскер (cyber terrorist), кибершабуыл (cyber attack), автоапат (car accident), автоәлем (car world), автоәуеcқой (car amateur), веложарыс (cycle competition), велосаяхат (cycle travel), антидағдарыс (anticrisis), экожүйе (eco system), экоорталық (eco centre), гидроұшақ (hydroplane), гидрожүйе (hydrosystem)

Internal prefix + external lexeme: no examples

Internal lexeme + external suffix no examples

External lexeme + internal suffix: авариялылық (dangerous), индукциялылық (inductive), инерциялылық (inertial) , инновациялылық (innovational), наградтау (to reward), идентификаттау (to identify), аттестаттау (to attest), каталогтау (to catalogue), асфальттау, зарядтау (to charge), аккумуляторлық (to accumulate), бизнес-инкубациялау (business- incubation), инспекциялау (to inspect), эвакуациялау (to evacuate), интрадыбыстық қару (intrasound weapon), гидрофобтық (hydrophobic), аппаратхана (instrument room) .

Abbreviation as a component of contamination: ЭКСПОкалипсис (EXPO calipsis)

Contaminants based on hybrid formations: уикимақ (уикипедия + ақымақ ) (Wiki + fool), нетұрғын (интернет + тұрғын) (net + citizen), фейсмолда (фейсбук + молда) (Facebook + mullah), фейсөкше (фейсбук + өкше) (Facabook + rumour), қатеррорист (қатер + террорист) (error + terrorist), Брекзиттену (Брекзит + тену) (Brexit + study), тойстаграм (той + инстаграм) (party+ Instagram), әмбеблогер (әмбебап + блогер) (universal + blogger), тойгустатор (той + дегустатор) (party+ taster), байбекю (бай + барбекю) (rich + barbecue), бабкер (бапкер + бабки) (money +professional), шашкриминация (шаш + дискриминация) (hair + discrimination), жаскриминация (жас + дискриминация) (age + discrimination), жемуар (жеу + мемуар) (eat + memoire), спонтсмен (спортсмен + понт) (sportsman + show off).

In the course of this research about 1,500 new units were analyzed, the analysis of these units showed that composite word formation (composition of 803 units) is the most productive word-formation type among the morphological ways of word-formation in the modern Kazakh language, affixation was no less than the actual word-formation type (616 units). The contamination (50 units) is not a traditional word-formation type; however, in the era of close linguistic contacts, the ubiquitous spread of the Internet and social networks and the widespread influence of the English language, contaminants are often found in modern Kazakh, especially in the media and Internet communications. Abbreviation is a very unproductive word-building type, according to the results of this study (Figure 4).

Figure 4

Morphosyntactic ways of word-formation in the Kazakh (Qazaq) language

As for hybrid formations, there are hybrid composites, derivatives and contaminants in modern Kazakh language formed according to the schemes presented above.

Among the hybrid formations, hybrid derivatives (287 units) come first. In the Kazakh language, derivatives with international prefixes (for example, auto, tele, hydro, eco, etc.) are increasingly encountered, and when a grammatical and morphological adaptation of a foreign word occurs, derivatives forming from the following model appear: an external lexeme + an internal suffix, which is indicative of the relative flexibility and loyalty of the Kazakh language.

Also there are hybrid contaminants (75 units) in the Kazakh language that are formed by soldering the internal and foreign lexemes (Figure 5).

Thus, speaking of integrative processes in the modern Kazakh language, it should be noted that there are hybrid coinages created with the help of Russian and English morphemes. Hybrid coinage demonstrates the flexibility and loyalty of the Kazakh language in the modern system of word formation.

Figure 5

Correlation between hybrid and non-hybrid

Transnominations, that is, new words combining the novelty of a word form with the meaning already transmitted by another form. The main goal of creating transnominations is to give a new, more emotional name to an object that already has a neutral name, and also reflects the tendency to use more expressive forms. However, in the Kazakh language, the main goal of creating transnominations is to solve the problem of normalization. In the process of forming the transnominations the following variants appeared: урбандалу/кеңтану /қалалану (urbanization); бикамерализм/ қоспалаталы парламент /екіпалаталы парламент (bicameral parliament) (ғаламдану/ жаһандану (innovative), and their parallel functioning is also explained by the breach of the principle of semantic concordance. and their parallel functioning is also explained by the breach of the principle of semantic concordance.

In addition, periodicals and terminology dictionaries contain the following variants: террор/лаңкестік (terror), кандидат/үміткер (candidate), дипломатия/мәмілегерлік (diplomacy), идентификация/сәйкестендіру (identification), адаптация/бейімделу (adaptation), адекватность/барабарлық (adequacy), актуализация/өзектендіру (actualization), акцент/екпін (accent), альтернатива/таңдау-балама (alternative), амбиция/мардат (ambition), билингвизм/қостілдік (bilingualism), богема/дегдарлар (Bohemia), айқындама/брифинг (briefing), девальвация/құнсыздану (devaluation). In this case, the word that becomes the backbone of the coinage and replaces the international term after a while is first used as an expressive synonym for the existing word, then, due to high frequency, loses its expressive coloring and becomes a neutral term, completely substituting the existing foreign word.

In new dictionaries, new terms can be found to denote international words which meaning Kazakh speakers have never met before, for example: ұлықтау (inauguration), бопса (blackmail).

Semantic innovations denote words with the new meaning determined by the form already available in the language. A feature of the modern Kazakh language is that many rethought words of the national language, dialecticisms, archaisms, ethnographic names, elements of expressive vocabulary undergo intensive lexicalization and become a neutral vocabulary. Thus, among the semantic neologisms of the Kazakh language, one can single out the rethinking of primordial words. These innovations include semantic induction, expansion and narrowing, metaphorization.

In the process of semantic expansion the words such as бәсекелестік (competition), ахуал (health), науқан (season), қарақшылық (robbery) have received the meaning of rivalry, situation, campaign, crisis and banditry. Semantic narrowing is used to form the terminological corpus, for example: кепілдік (guarantee), жиын (meeting), қадам (step), қақтығыс (incident), күйзеліс (depression).

Aldasheva (1992) distinguishes lexical innovations created by means of semantic induction in lexical transformations in the Kazakh language, implying a change in the meaning and appearance of a new meaning, i.е. semantic modification under the influence of a foreign source existing in the language and coincidence in the internal form. Neutral lexical units, in terms of their semantics, converge with foreign-language terms: there can be various rethinking of words and various semantic transformations of words under the influence of foreign vocabulary (semantic induction) жолдау (message), ұзарту (prolongation), жоба (project), қор (fund), көші-қон (migration); they acquire an expressive-tantalizing connotation: кемсітушілік (discrimination), бопса (blackmail), алапат апат (catastrophe). In such cases, an inaccurate (uncalculated) translation occurs, one of the semantic variants of the word is chosen for the definition of a foreign term, for example, мансапқорлық, generally used in the Kazakh language in the meanings of "careerism, vainglory" is used as the equivalent of the term "ambitiousness", ",B. Momynova (2005) uses the word билікқұмарлық (ambitiousness to power, authority) for this term in her dictionary. According to A. Aldasheva, semantic induction is a regular phenomenon in bilingualism in zones of parallel existence of different languages.

Metaphorization is also used as a means of creating semantic neologisms, in such cases the meaning of the word goes through the process of fixation by semantic transfer. In Kazakh, a metaphor can perform a nominative function, fix names for new phenomena and realities for which there are no established names for certain reasons (Kusainova 2006). Frequent use of metaphor makes it a cliche, for example, in Kazakh, "Tsusaukeser" often means "presentation" in newspapers, and in the explanatory dictionary of B.Momynova (2005), the following explanation is given: Тұсаукесер – алғашреттаныстырурәсімі (presentation of smth). It should be noted that the metaphor in the socio-political sphere of the Kazakh language, in addition to carrying an estimated load, is also a process that leads to the formation of new terms, clichés, and stock phrases.

Another example, reflecting the process of metaphorization as a process of creating semantic neologisms, can be cited from the field of modern information technologies. There is an evaluation function – the system of likes in social networks, in the Kazakh language the word лүпіл (heartbeat) replaces the English version of like: "Дінтанушы: Кейқыздархиджабтыжелідекөплүпілжинауүшінкиеді" (Stan.kz - Қазақстанжаңалықтары) - Theologian: Some girls wear hijabs in order to gain more likes (Stan.kz – News of Kazakhstan).

We can compare the ways of transferring this term in different languages:

English German Russian Kazakh

like Gefällt mir лайк лүпіл

It is worth noting different ways of transferring this phenomenon in different languages: for example, the German language uses a syntactic structure, in Russian transliteration is applied, and there is a semantic neologism based on metaphorization in the Kazakh language.

This research has demonstrated that word-formative trends undergo the external influence of the Russian and English languages, and this tendency is gradually increasing. Hybrid formations which are formed with the help of the Russian language elements are not occasions, this was happening for a long time, especially during the Soviet period. At that time a lot of Russian words entered the Kazakh word-stock, sometimes even without the process of assimilation, however, the Kazakh language in order to survive and to save its uniqueness worked out the mechanism of hybrid word formation, therefore a lot of hybrid words exist nowadays.

With the acquiring of Independence the question of the Kazakh language purity arose. There appeared a lot of ways and mechanisms to avoid using borrowings and hybrid words from the Russian language by replacing them with Kazakh words. Such words are created (in some way artificially) on the base of semantic congeniality, a great number of terminological dictionaries appeared and a lot of semantic innovations can be found in political and economic periodicals.

During past decades the importance of the English language boosted up all over the world, and the ability of speaking and understanding English is a necessary requirement for a competitive country with developing economic and political system. That is why Kazakhstan enacts laws to promote the English influence and recently president of Kazakhstan N. Nazarbayev signed a decree of using Latin graphics in Kazakh. Consequently, the borrowings from English enter the Kazakh language directly and now a lot of hybrid words with English elements are appearing in newspapers and periodicals.

Lexical innovations were collected from the Kazakhstani “Egemen Kazakakhstan” newspaper and “Azattyq news” platform articles, they were analyzed and productive word-formative types were pointed out. The most interesting examples were demonstrated in this article.

The article gives the definition of neologisms and the basic criteria of their identification: the novelty of form and meaning, the novelty of concept, etc.

The distinctive novelty of this article was the method for extracting Kazakh neologisms from the newspaper-based corpus.

The research has demonstrated that at the level of emergence of national new words the era of independence gives birth to such new concepts as contaminations, metaphorization and hybrid word-formative types in word-building. These new tendencies of Kazakh (Qazaq) word formation suggest further research fields to compare traditional word formation methods with such new non-classical ways. The scientific novelty of the work is that modern processes of linguistic integration and differentiation are analyzed on the basis of lexical innovations in Kazakh (Qazaq). Lexical innovations are studied in terms of their derivational characteristics and as the reflection of the influence of language contacts. The relevance of the study is determined by the constant increase in linguistic contacts in terms of language integration; the need to study the processes of linguistic integration and differentiation; the importance of understanding word formation tendencies in modern languages; constant increase in borrowings and hybrid entities in the English and Kazakh languages.

The growing tendencies of using words based on blending in Kazakh as the achieved novelty of this paper can be well implemented in the Kazakh word-formation courses for students majoring in Kazakh language and foreign (English) language. The following novelty of our paper, namely discussion of new concepts, like contaminations, metaphorization and hybrid word-formative types in Kazakh word-building theory would be a big contribution in enlarging the horizons of the existing Kazakh word-building theory, as it lacks such concepts as contaminations, metaphorization and hybrid word-formative types being limited by traditional word-formative types.

Aldasheva, A. (1992). Kazakh modern literature lexical use (based on the material of the periodical press in 1976-1991: PhD Thesis in Philology. Almaty: Abai Kazakh State Pedagogocal Institute.

Azattyq radio (2017-2018). https://www.azattyq.org/

Balakayev, M.B. (2007). Kazakh literary language. Almaty: Dyke-Press. ISBN 9965-798-54-0

Independent Kazakhstan [Egemen Kazakhstan]. (2017). https://egemen.kz/search-by-category-group/53

Isaev, S., and Nurkina, G. (1996) Comparative typology of the Kazakh and Russian languages. Almaty: Sanat. ISBN 5-7090-0116-3

Janssen, M. (2011). Orthographic Neologisms: selection criteria and semi-automatic detection (unpublished manuscript available at http://maarten.janssenweb.net/Papers/neologisms.pdf)

Kotelova, N. Z. (2015). Selected works. Russian Academy of Sciences; Institute of Linguistic Researches. St. Petersburg: Nestor-Istorya, pp.189-192. ISBN 978-5-4469-0705-2 (in Russian)

Kusainova, G. S. (2006). Functional aspect of the political metaphor on the pages of Kazakh-language and English-language newspapers: author's abstract of PhD Thesis in Philology. Almaty: Kazakh Ablai Khan University of International Relations and World Languages.

Oralbay, N. (2007). Morphology of Contemporary Kazakh Language. Almaty: LLP Inzhu-Marzhan, pp. 134-143. ISBN 9965-545-57-Х (in Kazakh)

Paryzek, P. (2008). Comparison of selected methods for the retrieval of neologisms. Investigationes inguisticae, 16,163-181. DOI: 10.14746/il.2008.16.14

Rey, A. (1995). Essays on Terminology. Translated and Edited by Juan C. Sager. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-9027216083

Stenetorp, P. (2010). Automated Extraction of Swedish Neologisms using a Temporally Annotated Corpus. Master of Science in Engineering (MSc Eng) Thesis, Royal Institute of Technology (KTH), Stockholm, Sweden. http://pontus.stenetorp.se/res/pdf/stenetorp2010automated.pdf. ISSN-1653-5715

Syzdyk R. (2004) History of the Kazakh literary language (XV-XIX centuries) Қазақ әдеби тiлiнiн тарихы (ХV-ХIХ ғасырлар). Almaty: Arys. ISBN 9965171998 .

1. PhD student, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University. Astana, Kazakhstan. Contact email: sagima.s.2007@mail.ru

2. PhD student, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University. Astana, Kazakhstan. Contact email: aselasel_1991@mail.ru

3. Doctor of Sciences (Philology), Professor L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University. Astana, Kazakhstan. Contact email: a_bizhkenova@mail.ru

4. Candidate of Sciences (Philology), Associate Professor, L.N.Gumilyov Eurasian National University. Astana, Kazakhstan. Contact email: mad-anafinova2018@mail.ru

5. Candidate of Sciences (Philology), Associate Professor, L.N.Gumilyov Eurasian National University. Astana, Kazakhstan. Contact email: Leylasabitova95@mail.ru