Vol. 39 (Number 34) Year 2018 • Page 9

CANO, Jose A. 1; TABARES, Alexander 2

Received: 16/03/2018 • Approved: 25/04/2018

ABSTRACT: This article identifies the main characteristics of nascent and active entrepreneurs. We use the information from the GUESSS Colombia 2013/2014 study. Main findings show that the rate of nascent and active entrepreneurs in Colombia is higher than worldwide and that the main industry sector of planned and existing firms are trade and ICT industries. Likewise, nascent entrepreneurs start up their firms with partners, while active entrepreneurs contribute with the majority of the equity, considering that they perform better than competitors and are optimistic with the growth of their firms. |

RESUMEN: Este artículo identifica las características de los emprendedores nacientes y activos. Se utiliza la información del estudio GUESSS Colombia 2013/2014, señalando que la tasa de emprendedores nacientes y activos es mayor que a nivel mundial, y que los principales sectores industriales para el emprendimiento son el comercial y el de TIC. Igualmente, los emprendedores nacientes inician sus empresas con socios, mientras que los emprendedores activos aportan la mayoría del capital de sus empresas, considerando que se desempeñan mejor que sus competidores y son optimistas con el crecimiento de sus firmas. |

Since 2003, the GUESSS Project (Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students' Survey) has globally researched the entrepreneurial intentions of university students with the aim of identifying why students have already created a business or are planning to found their own business (Sieger, Fueglistaller, & Zellwegr, 2016).

Within the basic structure of the GUESSS reports, there is a chapter dedicated to nascent entrepreneurs, who are in the process of starting up their new ventures, and another chapter dedicated to active entrepreneurs, who are CURRENTLY running their own business or are self-employed (Edelman, Manolova, Shirokova, & Tsukanova, 2016; Sieger et al., 2016). These groups of students represent those whose career intention is focused on entrepreneurship, thus they are the most important groups to analyze within a university environment.

Generally, the role of universities is focused on research and teaching, which should be complemented with entrepreneurship activities, since these three substantive functions of universities are complementary and linked to each other. Even when the universities include acceleration programs and pre-incubation of business ideas, entrepreneurship is improved in students and new graduates, because seed capital is provided to entrepreneurial students to refine the business model, develop prototypes, products, and services (Beyhan & Findik, 2017).

In this sense, it is important the accompaniment not only of the universities to the enterprising students but also of the families, because the family environment has the potential to supply young nascent entrepreneurs with social support that enables them to establish firms (Edelman et al., 2016). All this entrepreneurial ecosystem should guide new entrepreneurs in their decision-making process because nascent entrepreneurs rely significantly on subjective and often biased perceptions rather than on objective expectations of success when they are making decisions (Arenius & Minniti, 2005).

This situation can be argued to the extent that as the student's education level increases, the student's intention to be a founder decreases as well, and students with high academic performance have stronger intentions to be employees (Cano, Tabares, & Alvarez, 2017).

As a consequence, a large part of nascent entrepreneurs decide to start up their own firms before determining the success or failure of their entrepreneurial initiatives (Carter, Gartner, Shaver, & Gatewood, 2003), in order to respond to personal motives and aspirations, rather than responding to economic and environmental constraints (Hikkerova, Ilouga, & Sahut, 2016). Within the personal motives and aspirations can be mentioned the lifestyle, the independence for decision-making, and the grants of exploiting their skills in the creation of products and services (Álvarez, Cano, Yepes, & Aparicio, 2013; Cano & Tabares, 2017).

On the other hand, it is highlighted that entrepreneurial intentions are stronger in developing countries and weaker in developed countries (Cano et al., 2017). However, an attractive approach for public policy in developed countries is the improvement of incentives for the creation of companies and enterprises; while for developing countries the preferences focus on economies of scale, encourage foreign direct investment and promote management education (Wennekers, Van Wennekers, Thurik, & Reynolds, 2005).

For the specific Colombian case, the nation needs to improve the effectiveness of the entrepreneurship education and promote projects providing social and economic impacts (Cano & Tabares, 2017). Therefore, it is necessary to study within the university students the behavior of nascent entrepreneurs and active entrepreneurs, WHO as such represent future entrepreneurs, and in turn will be one of the most powerful economic forces in modern societies (Sieger et al., 2016).

Accordingly, this article intends to identify the main personal characteristics and the characteristics of companies founded by nascent entrepreneurs and active entrepreneurs in Colombia. The article is structured as follows. After this introduction, we introduce the details of the research methodology. The third section discusses the empirical results of the study. Finally, we present the most relevant conclusions of this study.

To analyze the personal and business characteristics of the nascent and active entrepreneurs, the information generated in the Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students' Survey (GUESSS) is used. THE data from the GUESSS Colombia edition 2013/2014, led by the Universidad de Medellin AND conducted in six universities, providED a final sample size of 801 students, and ALLOWED TO compare the results WITH the data from the International Report GUESSS 2013/2014 (Sieger, Fueglistaller, & Zellweger, 2014).

The GUESSS Colombia study, in addition to broadly investigating the entrepreneurial career intentions of the university students and the determinants of entrepreneurial intention (Cano & Tabares, 2017; Cano et al., 2017), also focuses on nascent entrepreneurs and active entrepreneurs. In this sense, the GUESSS study asks all students if they are thinking of starting up their own firm in the coming months or if they have already created it, in order to identify whether the students are nascent or active entrepreneurs.

Thus, Figure 1 presents the percentage of active and nascent entrepreneurs in Colombia, highlighting that 39.9% of the students are classified as entrepreneurs because they already have started actions to create a company or even they already have their own employees and their firms are already billing. In detail, 26.8% are nascent entrepreneurs with the prospect of creating a company, and 13.1% are active entrepreneurs with an own firm.

Figure 1

Nascent and active entrepreneurs in Colombia

The personal characteristics and the characteristics of planned and existing firms will be analyzed in order to identify behaviors and performances obtained in the entrepreneurial initiatives of university students in Colombia, as well as the type of business model, the industry, investment, work team among others. Likewise, the results are contrasted with the global report of Sieger et al. (2014), to find differences and similarities of university entrepreneurship in Colombia and the rest of the world.

This section presents the results of the personal characteristics of the nascent and active entrepreneurs in Colombia, as well as the characteristics of planned and existing firms.

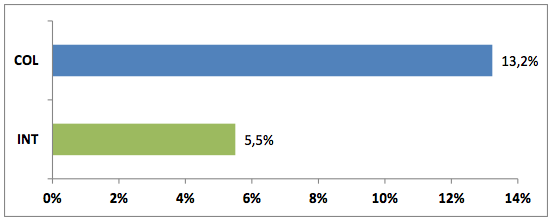

Figure 2 shows that Colombia has a percentage of nascent entrepreneurs above the world average (like other countries with developing economies), with an additional 11.7% of share relative to the international sample. This contrasts with the developed countries where the percentage of nascent entrepreneurs is below the average, suggesting that the rate of nascent entrepreneurs is inversely proportional to the development of the countries to which they belong.

Figure 2

Nascent entrepreneurs – Colombia vs International

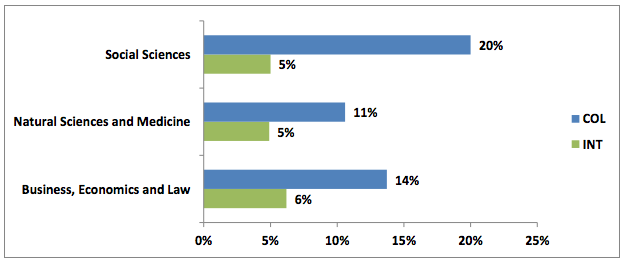

Likewise, when comparing the percentages of nascent entrepreneurs by study field, higher levels are observed in Colombia with respect to the international sample, with additional values over 9% for Colombia, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3

Nascent entrepreneurs across field of study – Colombia vs International

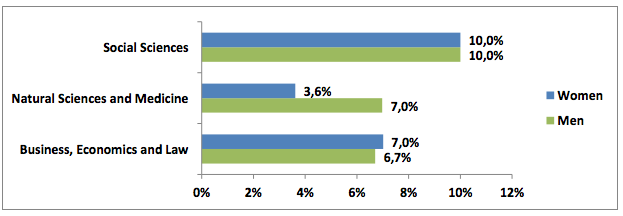

To obtain a better understanding of these data, Figure 4 presents the percentage of nascent entrepreneurs in each study area according to gender. There it is evident that in Colombia the participation of men is higher than the participation of women within each study area, presenting greater differences in the area of natural sciences and medicine, and in the area of social sciences.

Figure 4

Nascent entrepreneurs across field of study and gender

Regarding the activities performed by nascent entrepreneurs for the creation of their own firm, Figure 5 presents a comparative analysis of the sample in Colombia and the international sample. In both samples, the most important activities when creating a firm are related to gathering information about markets and competitors, followed by promoting the firm to potential customers who can buy the products or services. In contrast, less important activities, but not irrelevant when creating a firm, have to do with registering the company and applying for a patent, copyright or trademark.

Figure 5

Activities of nascent entrepreneurs to create their own firms

These latest data reflect a high degree of informality in the nascent enterprises taking into account that many of the good business opportunities are lost because they are not legally constituted or simply lose competitiveness by not registering patents or commercial rights. This situation puts at risk in the sense that others appropriate the business idea or get the potential market share. Figure 5 highlights that in Colombia all the activities performed when creating a company have a higher percentage than in the international sample, except in the activities of gathering information of markets and competitors, registering the company and/or patents, and in not having performed any activity yet.

Regarding the business industry where university students intend to create their own firms, Figure 6 shows that wholesale and retail trade is the most attractive industry in Colombia and in the international sample, followed by the ICT industry. There is a very marked difference between the Colombian and international sample in the wholesale and retail industry, suggesting that many of the entrepreneurs in Colombia see great opportunities in the commercialization and distribution of products and services. If these data are related to the activities performed to create an own firm, it can be revealed a level of informality in the commercial industry for the nascent entrepreneurs, taking into account that in Colombia the formal registration of a company is not a priority when starting up a business.

Figure 6

Industry sectors of planned firms

To analyze the novelty of the product and/or services offered by nascent entrepreneurs, Figure 8 shows that in Colombia 51.9% of nascent entrepreneurs perceive that their products or services are innovative for the majority of customers, which is above the international average. Even at the international level, 24.3% of nascent entrepreneurs perceive that their planned firms are not novel for any customer, while in Colombia this percentage is only 10.8%, which means that worldwide there is a higher initiative to imitate existing offers of products and services. It can be explained due to the poor development of local markets, and the great possibilities of growth that Colombia is experiencing as a developing economy.

Figure 7

Degree of newness of the products/services of planned firms

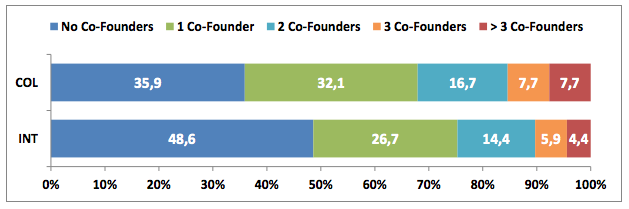

On the other hand, Figure 8 shows that in Colombia 80.1% of entrepreneurs plan to start up their own firms with co-founders that can provide knowledge or financing, while 19.9% of nascent entrepreneurs are creating their firms without partners. compared to the international sample, 27.3% of the students intend to start up their firms without partners.

Figure 8

Number of co-founders among nascent entrepreneurs

Active entrepreneurs in Colombia vary considerably when compared to the rest of the world. Figure 9 shows that in Colombia there is a greater share of self-employed students. As a relevant data, the highest rates of active entrepreneurs globally are found in Colombia, Argentina, Malaysia and Mexico (Sieger et al., 2014), a fact that confirms once again that developing countries have a greater entrepreneur intention and participation than in developed countries.

Figure 9

Active entrepreneurs – Colombia vs International

Regarding the areas of study, Figure 10 indicates that in Colombia there is a greater number of active entrepreneurs in the area of social sciences, followed by administrative sciences and law; and in each of these areas, Colombia has a greater share of active entrepreneurs relative to the international sample. These differences suggest that Colombia is one of the countries with a greater share of active entrepreneurs, and it is coherent with the high rates of entrepreneurial intention shown in Figure 1.

Figure 10

Active entrepreneurs across field of study – Colombia vs International

To develop this issue further, Figure 11 presents an analysis in Colombia by study field according to the gender of the students. In this case, unlike the behavior of nascent entrepreneurs, the participation of women is higher in the area of administrative sciences and law, and equals the share of men in the area of social sciences. In the area of natural sciences and medicine, the participation of men is about twice women.

Figure 11

Active entrepreneurs across field of study and gender

Analyzing the founding years of the already created firms, we find data of great interest in Figure 12. Both the Colombia study and the international study show that the firms are very young, to the point that in Colombia 82.9% of firms were created in the last 3 years, while worldwide 59% of firms were created in the same period. This information confirms that in Colombia the firms created by university students have few years of founding, while worldwide there is a significant percentage of enterprises founded more than 10 years ago.

Figura 12

Founding years of the existing firms

Regarding the industries where active entrepreneurs develop their firms, Figure 13 shows similar results to those shown in Figure 6 for nascent entrepreneurs, where the most attractive industry is the retail and wholesale trade, followed by the ICT industry, both in Colombia and internationally.

Figure 13

Industry sectors of existing firms

In addition, a large share of active entrepreneurs firms focus on providing services. However, a relevant fact for Colombia is the low participation of firms in tourism and health services, taking into account that the country is recognized worldwide for its knowledge and good practices in the provision of services in the fields of medicine, as well as for its natural diversity and tourist destinations. These facts invite entrepreneurs to explore and to take advantage these Colombian industries.

The study also determines the percentage of active entrepreneur own capital invested in the creation of a firm. Figure 14 shows that 54.7% of Colombian active entrepreneurs contribute more than half of the equity required with their own funds. The international study indicates that 73.2% of active entrepreneurs invest more than 50% of the equity required by their firms. This suggests that globally the entrepreneurs start up their firms with a large part of own-capital and does not leverage the investment with other entities.

Figure 14

Equity share of active entrepreneurs

Figure 15 analyzes the number of people associated with active entrepreneurs to start up their firms, identifying that 64.2% of colombian active entrepreneurs start up their firms with partners, especially with one partner, who can provide knowledge and/or financing. At the international level, the tendency to create firms without partners is greater than in Colombia at 12.6 percentage points.

Figure 15

Number of co-founders among active entrepreneurs

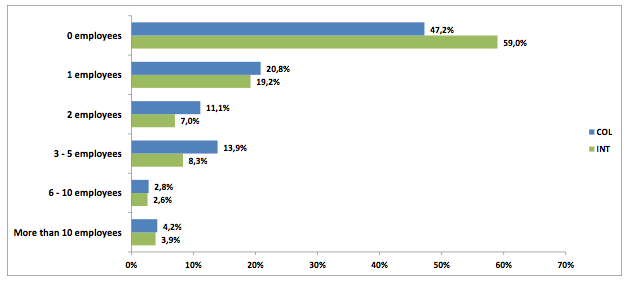

In order to determine if the company is developing commercial activities and generating employment, Figure 16 shows the number of full-time employees that active entrepreneurs hire in their companies. According to this, at the national and international level, one-person firms predominate, thus entrepreneurs are founders, managers, and employees simultaneously. It is observed that active entrepreneurs’ firms generate less employment worldwide than in Colombia, highlighting that in Colombia 21% of active entrepreneurs hire three or more employees in their firms.

Figure 16

Employees (full-time equivalent) in the existing firms

As a complement to the abovementioned, the GUESSS study analyzes the growth intention and aspiration of active entrepreneurs. Figure 17 depicts the intention to grow as the expected increase of full-time employees in the next 5 years. It is evident that at the national level there is an optimistic intention of growth, where 63.4% of active entrepreneurs have very strong expectations and intentions to increase the number of employees at a higher rate of 4 times, while in the international sample the intention of growth is more conservative.

Figure 17

Growth intentions of active entrepreneurs

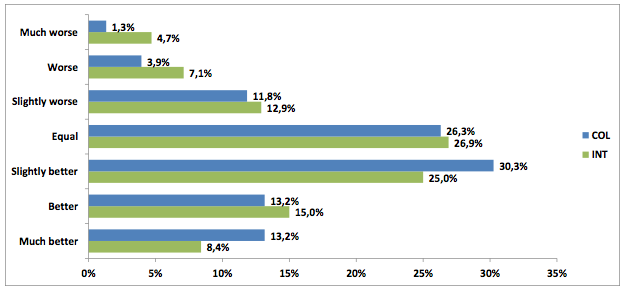

The GUESSS study also analyzes the performance of entrepreneurial students’ firms according to their competitors. Figure 18 shows that national and internationally, AROUND half of active entrepreneurs perceive a better performance regarding their competitors. In addition, about 17% of active entrepreneurs in Colombia expect a lower performance relative to competitors, while internationally about 25% of active entrepreneurs expect a lower performance relative to competitors.

Figure 18

Performance of existing firms relative to competitors

Consequently, the GUESSS study allows determining that in Colombia the share of nascent and active entrepreneurs is higher than the global trend, even within each study field, preferring the wholesale and retail trade industry, and the industry of the ICT to start up a firm or to be self-employed. Similarly, greater optimism is perceived in Colombia with respect to the rest of the world in terms of the degree of novelty in the planned firms and the performance of existing firms owned by university students. Finally, compared to the international sample, Colombia presents a greater tendency to have partners in planned firms and existing firms.

The GUESSS study allows TO find important differences in nascent entrepreneurs from developed and developing countries. Thus, Colombia is one of the countries with a greater entrepreneurial activity relative to the international sample and presents greater optimism and expectations regarding the novelty and innovation of the products and services offered.

Therefore, in Colombia, nascent entrepreneurs are a significantly higher share than at the international level in each of the study areas, with a higher tendency in the male gender. These nascent entrepreneurs are more prominent among students in the area of administrative sciences. The most important activities when creating a firm in Colombia are related to gathering information about markets and competitors, followed by showing the business to potential customers who can buy the products or services. Hence, the GUESSS Colombia study shows a level of informality in nascent entrepreneurs, taking into account that in Colombia the formal registration of the company is not a determining factor. Likewise, the study in Colombia indicates that 80.1% of entrepreneurs plan to start up their own firms with partners who can provide knowledge or financing, leveraged efforts, and skills.

On the other hand, the GUESSS study identifies that Colombian active entrepreneurs rate is higher than at a global level, presenting gender shares more equitable, and evidencing that the majority of active entrepreneurs firms have less than a year of creation. The study also indicates that active entrepreneurs usually start UP their firms with a capital contribution of more than 50%; these firms are generally considered better performing than their competitors are, and the active entrepreneurs have optimistic aspirations for the growth of full-time employees.

ÁLVAREZ, C., CANO, J.A., YEPES, M., & APARICIO, S., (2013). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Antioquia - GEM. Medellín, Colombia: Editorial Universidad Nacional de Colombia.

ARENIUS, P., & MINNITI, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 233–247.

BEYHAN, B., & FINDIK, D. (2017). Student and graduate entrepreneurship: ambidextrous universities create more nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Technology Transfer, 1–29. Springer US.

CANO, J. A., & TABARES, A. (2017). Determinants of university students' entrepreneurial intention: GUESSS Colombia study. Espacios, 38(45), 22. Retrieved from http://www.revistaespacios.com/a17v38n45/17384522.html

CANO, J. A., TABARES, A., & ALVAREZ, C. (2017). University students' career choice intentions: GUESSS Colombia study. Espacios, 38(5), 20. Retrieved from http://www.revistaespacios.com/a17v38n05/17380520.html

CARTER, N. C., GARTNER, W. B., SHAVER, K. G., & GATEWOOD, E. J. (2003). The career reasons of nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 13–39.

EDELMAN, L. F., MANOLOVA, T., SHIROKOVA, G., & TSUKANOVA, T. (2016). The impact of family support on young entrepreneurs’ start-up activities. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(4), 428–448.

HIKKEROVA, L., ILOUGA, S. N., & SAHUT, J. M. (2016). The entrepreneurship process and the model of volition. Journal of Business Research, 69(5), 1868–1873.

SIEGER, P., FUEGLISTALLER, U., & ZELLWEGER, T. (2014). Student Entrepreneurship Across the Globe: A Look at Intentions and Activities. St.Gallen: Swiss Research Institute of Small Business and Entrepreneurship at the University of St.Gallen (KMU-HSG).

SIEGER, P., FUEGLISTALLER, U., & ZELLWEGR, T. (2016). Student Entrepreneurship 2016: Insights From 50 Countries. St.Gallen/Bern: KMU-HSG/IMU.

WENNEKERS, S., VAN WENNEKERS, A., THURIK, R., & REYNOLDS, P. (2005). Nascent entrepreneurship and the level of economic development. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 293–309.

1. Universidad de Medellín. Industrial Engineer, Master in Administrative Engineering. jacano@udem.edu.co

2. Universidad de Medellín. Language professional, Master in Administration. atabares@udem.edu.co