Vol. 39 (Number 34) Year 2018 • Page 4

Ana María BARRERA RODRIGUEZ 1; Orlando RODRIGUEZ 2

Received:23/02/2018 • Approved: 15/04/2018

ABSTRACT: What are the differences in terms of internal identification in public, private, and hybrid organizations? This paper answers the question by reflecting on the influence that governance structure has on informal institutions. The theoretical framework links New Institutional Economics with Corporate Communication Theory. The paper highlights that workers in private firms have a higher degree of internal identification. Employees in the hybrid sector describe having a medium degree. Workers in the public sector have the least amount of internal identification. |

RESUMEN: ¿Cuáles son las diferencias en términos de identificación interna en organizaciones públicas, privadas e híbridas? Este documento reflexiona sobre la influencia que tiene la estructura de gobernanza en las instituciones informales. El marco teórico vincula la Nueva Economía Institucional con la Teoría de la Comunicación Corporativa. Destaca que los trabajadores en empresas privadas tienen un mayor grado de identificación interna, los del sector híbrido tienen un grado medio y los del sector público tienen el menor grado de identificación interna. |

This paper enquires into specific informal institutions that have emerged from each type of governance structure. Specifically, the paper addresses the question: what are the differences in terms of internal identification in public, private, and hybrid organizations?

The authors seek to answer this question by using comparative methods (Ebbinghaus, 2006; Creswell, 1994). The research compares key points relating to company identification, which play a role for public, private, and hybrid organizations. The independent variable is governance structure: the public, private, and hybrid sectors, and the dependent variable is internal identification in terms of organizational culture, recognition with the values, status, and labor satisfaction.

The theoretical approach is based on Institutional Communication (Iacob & Iacob, 2016; Lammers, 2011), which is the exchange of information among individuals or organizations, based on following standardized processes. This theoretical framework links New Institutional Economics (North, 1990; Coase, 1992; Menard, 2004) with Corporate Communication (Lammers & Barbour, 2006). Internal identification can be defined as the coherence between the values, expectations, and culture of individuals with the organization for which they work (Capriotti, 2009).

Labor management is an important issue within organizations, and labor performance is the foundation of competitiveness (Lammers & Barbour, 2006). Furthermore, workers are the ones who have the real contact with the stakeholders: customers, suppliers, distributors, competitors, and any other interest group. A satisfied employee works more productively; therefore, the authors expect there to be a direct relationship between internal identification and competitiveness: the more the workers identify with the organization, the more competitive the organization will be. Nevertheless, different governance structures have an effect on internal identification due to organizational culture, status, and how the workers relate to the company. Entities should be aware of differences so that they can design the most pertinent strategies to resolve the problems implicit in each governance structure, such as motivation and leadership.

Resemblance and status differ depending on the governance structure: private, public, or hybrid (Menard, 2004). The three organizational structures have different targets and routines; furthermore, there are differences in terms of the perception that employees have of the organization in which they work. These elements lead to differences relating to internal identification.

The empirical evidence used in this paper was based on field research regarding a sample of 400 workers in public, private, and hybrid organizations in the city of Pereira, Colombia. Pereira is a Latin American city containing 500 thousand inhabitants that is located in the Colombian Central West: 320 kilometers from the capital city, Bogota. Pereira is the second Colombian city that features in the World Bank’s Doing Business ranking (WB, 2017).

The paper highlights that the workers in private firms have a higher degree of internal identification than employees in the both public and hybrid organizations. Workers in private companies perceive that they have a higher status in the companies. Furthermore, private workers report to be very satisfied and well compensated for their effort in undertaking daily tasks. Therefore, private firm employees develop higher recognition with their company’s values. Internal identification is an informal institution that performs better in organizations with market-oriented governance structures.

Institutions are norms: Douglass North (1990) points out that institutions could be either informal or formal. Informal institutions are unwritten rules; for instance, belief systems, habits, behavioral patterns, or cultural traditions (Menard & Shirley, 2005). Conversely, formal institutions are written rules, such as the law, a constitution, agreements, or contracts. Formal institutions determine property rights and governance structure. Ronald Coase (1992) suggests that institutions are the key to opening the firm’s ‘black box’. Analyzing the institutional structure of production provides understanding about an organization. Labor is a significant internal resource, which should be institutionalized to reduce transaction costs and achieve higher efficiency. Moreover, this paper focuses on the analysis of formal institutions through governance structure. According to Oliver Williamson (1996), every governance structure requires a discrete structural analysis, and there are specific differences for each type of structure. However, this research analyzes informal institutions that are represented by internal identification. New Institutional Economics (NIE) provides a pertinent theoretical scope to be able to study internal relations within organizations. NIE focuses on the abstract individual and the sources that influence their understanding about economic relations (Hodgson, 1993).

Governance structure refers to the whole political institutional framework including the civil servants, the legislation, and the formal institutions that determine the behavioral framework of public agents. Governance structure includes organizations that exert some political control. There are three categories in governance structure: those that are market-oriented, those that are hierarchy-oriented, and hybrid forms (Menard, 2004). Governance structure is market-oriented when it is led by supply and demand. Private firms are ruled by governance structures that are market-oriented, and their goal is to increase profits. Second, governance structure is hierarchy-oriented when public organizations centralize the making decision process. The aim of hierarchy-oriented organizations is to control social actors, encouraging their development. Finally, hybrid forms of governance structure are developed from mixing the two previous: market-oriented and hierarchy-oriented structures. For instance, NGOs are developed from hybrid governance structures. NGOs are funded by private capital, but their goal is to ensure that a certain segment of society develops. Governance structure takes place due to relations between actors and the organization’s political structure.

The authors expect that organizations that have similar governance structures behave with similar orientations: market, hierarchy, or hybrid. Organizations are not synonymous with institutions. Organizations are a group of individuals, interacting to achieve a common goal, but institutions drive organizations (Menard, 1997). The literature describes how institutions from one organization could be imitated by other organizations (DiMaggio & Powell, 1999). Organizations have their own corporate identity that allows them to adopt an institutional framework. However, some organizations could adopt institutions from external organizations to make it easier to achieve their own goals. Institutional isomorphism is based on organizational management, which takes institutions from an external organization and then implements them in another organization. This organization, therefore, uses the values, behavior, or norms of another. There are two types of institutional isomorphism: coercive and mimetic. Coercive isomorphism is driven forward by political pressure; however, mimetic isomorphism is a willing problem-solving strategy, which is based on imitating another organization. On a deeper level, institutional isomorphism describes how the institutional framework of the organization can be identified. However, is it possible to develop institutional identification among internal stakeholders? Does internal identification depend on the governance structure? Do informal institutions change governance structures?

Informal institutions interact with governance structures (Furubtotn & Richter, 2005). Internal identification is an informal institution, which shapes workers’ attitudes, according to the organizational values. Internal identification is an organizational strategy oriented towards building informal institutions. Witting (2006) points out that internal identification links the principles relating to group relevance, group prestige, and resemblance. The goal is to link the corporate platform such as the mission and the vision with the workers’ motivation and behavior. The outcome is the coherence between the way that the employees act, think, and feel with corporate values (Kuhn, 2005).

David Whetten and Stuart Albert (2006) view internal identification as “what the members perceive as the central, distinctive and lasting issue in the organization”. Based on this, the central issue defines the most important attributes, which allow the organization to be what it is. Also, the distinctive issue focuses on the features that make the organization different from others. Finally, the lasting issue refers to how the employee conceives the organization over time, despite any changes.

Internal identification has four fundamental features (Van Knipenberg & Van Schie, 2000). First, there is the psychological perception of the worker’s self and how this is connected to the group or the organization; second comes the worker’s narrative regarding his/ her experience of success or defeat at the organization; in third place is the coherence of personal values with the organization’s values; and, finally there is the self-description in terms of belonging to the organization.

Paul Capriotti (2009) argues that the main element of internal identification is the corporate culture. “Corporate Culture is the set of beliefs, values and rules of conduct, shared and not written, by which the members of an organization are ruled. Corporate culture is reflected by the workers’ behavior” (Capriotti, 2009).

Corporate culture is a phenomenon (Capriotti, 2009); every organization has it, even if it is not formally determined. All workers are immersed within their corporate culture, even if they are new in the organization or have been there for a long time. The level on which employees share the values and behaviors that represent the corporate culture defines to what extent they have integrated and belong to the group. However, if a worker is becoming distant from the values shared by the group, he will feel isolated (Cornelissen, Joep; Durand, Rodolphe; Fiss, Per; Lammers, John & Vaara, Eero, 2015).

Within any organization, there is a general corporate culture; nevertheless, Capriotti (2009) points out that there are corporate subcultures among the workers who interact daily. For instance, every functional department could have different subcultures, but these do not contradict the general corporate culture.

Managers of the organization must design mechanisms so as the elements of the corporate culture are coherent with the corporate philosophy. The first step is to determine the current corporate culture (Capriotti, 2009). Second, managers should design their desired corporate culture and the path they aim to take to achieve it. Internal identification is developed based on three main factors: First, the sociological factors that include beliefs, rituals, values, norms, myths, taboos, and linguistic habits. Second, direction factors that refer to the organizational structure, the managerial strategies, the systems and processes, the style of direction, and the control systems. Finally, the communication factors include both the internal and external communication (Rogala & Bialowas, 2016).

Other factors that determine internal identification, according to Daan Van Knipenberg and Van Schie (2009), include status, resemblance, and group size. Status refers to the organizational prestige. On a deeper level, status is how workers think the organization is perceived by external stakeholders. Second, resemblance occurs when the individual is perceived to be psychologically connected with a group; it could be influenced by the role that group dynamics have on the individual. Finally, group size is inversely proportional to internal identification: smaller groups have a higher degree of employee internal identification.

Additionally, labor satisfaction shapes internal identification (Topa, 2007). It can be described as having a generally pleasant emotional attitude towards the job, which is based on having proper experiences with the organization. Labor satisfaction has a major impact on internal identification , and it leads to stronger commitment towards the organization.

Broadly speaking, internal identification is an informal institution, shaped by the coherence between corporate culture and workers’ values. It is constructed by a company’s status and how the worker fits in with organizational values, which, in turn, leads to labor satisfaction.

The research question is answered using comparative methods (Ebbinghaus, 2006; Creswel, 1994): employee perception is compared for three different organizational structures. Comparative methods allow for similarities and differences to be found between the case studies. Specifically, the variables are compared for organizations with different governance structures: those that are market-oriented, those that are hierarchy-oriented, and hybrid forms.

Three variables were then compared (Table 1). The independent variable describes the governance structures: market-oriented private firms, hierarchy-oriented public organizations, and hybrid forms NGOs. The dependent variable is internal identification, which is described by how workers psychologically relate to the organization’s values, the perception of organizational status, and labor satisfaction.

Table 1

Operationalization of variables

Independent Variable GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE |

Dependent Variable INTERNAL IDENTIFICATION |

Public organizations Private firms NGOs |

Resemblance Status Labor satisfaction |

Source: authors.

The comparison is based on worker perception. There is a 283,0000 person labor force in Pereira (Dane, 2017); however, according to a report from October, 2015 Dane (2017), those employed with a formal contract is registered at 179,960. This paper only takes into account those people with formal jobs as having a contract provides employees with a minimum set of labor standards (ILO, 2017). There were 134,000 individuals hired by private firms. There were 12,000 individuals who were employed in public organizations. Moreover, according to the Pereira Chamber of Commerce (2017), there were 33,960 individuals working in non-governmental organizations (NGO).

The sample was obtained using the proportional stratified random method. The stratified random sampling "consists of dividing the universe in two or more groups 'strata' and obtaining a sample of each of them (...) this method takes into consideration certain characteristics known about the population who is studied" (Cifuentes, Cifuentes & Sabogal, 2001). Particularly, in proportional stratified random sampling, "the election of the units of every stratum is carried out in direct relation to the largeness of the diverse strata" (Cifuentes, Cifuentes & Sabogal, 2001). Therefore, the following results were achieved from the sample formula:

Table 2.

Sample formula conventions

N |

Population |

Infinite population (> 100 thousand) |

p |

Probability of occurrence |

50 |

q |

Probability of not occurrence |

50 |

e |

Sampling error % |

5 |

Z |

Confidence level 95.5% |

1.96 |

n |

Sample |

400 |

Source: Cifuentes, Cifuentes & Sabogal, 2001.

Table 3

Proportional stratified random sample

Strata |

Population |

Percentage |

Stratified sample |

Workers in private firms ** |

134,000 |

74.46 |

298 |

Workers in public organizations ** |

12,000 |

6.67 |

27 |

Workers in hybrid structures*** |

33,960 |

18.87 |

75 |

TOTAL |

179,960 |

100.00 |

400 |

Source: Cifuentes, Cifuentes & Sabogal , 2001

*** Source: Data from the Pereira Chamber of Commerce (2017)

** Source: Data from DANE (2017)

The proportional stratified random sample consists of 400 people: 298 workers for private firms, 27 employees in public organizations, and 75 individuals working in NGOs. The systematization of data was configured using the SPSS software – Statistical Package for Social Science.

Internal identification is the coherence between values, expectations, and an individual’s culture within the organization for which they work (Capriotti, 2009). Therefore, internal identification is shaped by informal institutions. To what extent workers relate to the organization’s values, the status of the organization, and labor satisfaction constitute internal identification.

Resemblance is the coherence between the individual’s belief systems and that of both their co-workers and the organization. First, resemblance is analyzed according to the coherence that individual behavior has with that of coworkers’. Second, resemblance can be seen in how employees identify with their coworkers. Finally, resemblance can be described according to the influence the company has in terms of employee beliefs, values, and behavior.

Primarily, coherence in terms of how workers identify with coworkers allows us to understand the affinity between individuals in the work place. The majority of workers usually identify with their colleges in the organization.

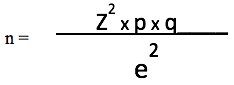

Employees in private firms describe having a higher degree of identity with their coworkers by up to 56.33 per cent (percentage who answered that they always identify with their colleagues). 65.8 per cent of workers in the hybrid sector answered that they usually identity with colleagues. Finally, public organizations register the least amount of identity. 44.44 per cent of workers answered that they sometimes identify with their co-workers. 40.74 per cent of employees in the public sector answered that they usually identify with colleagues. Overall, employees in private firms believe they have a higher degree of identification with their teams. Conversely, workers in public organizations usually feel that they identity with their coworkers.

Figure 1

Do you identify with your co-workers? (%)

Source: Authors

Moreover, resemblance points out the individuals’ level of coherence, in relation to the group, within the work environment. 48.64 percent of the total number of workers questioned stated to always perceive coherence between the individual’s behavior and that of their coworkers. Also, 35.98 percent of surveyed individuals answered that there was usually coherence. Therefore, there was a high degree of coherence between the individual and the group.

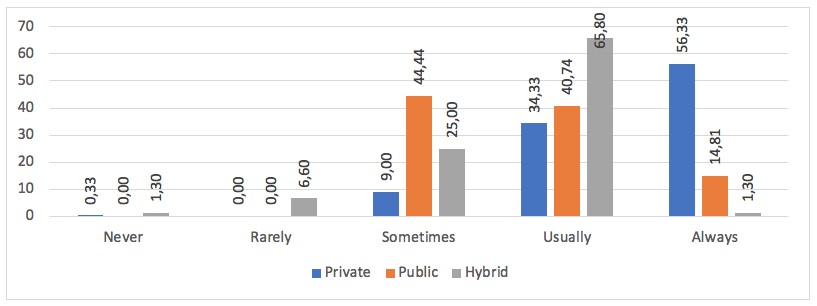

Overall, according to the survey, it was shown that there was resemblance between the collective behavior of coworkers and the individual’s behavior. The answers were robust for the organizations with the three types of governance structures: private, public, and hybrid. The highest level of resemblance was described in private companies and hybrid organizations. The main share of individuals answered that there is always coherence (47.67 per cent for the private firms and 65.79 per cent for the hybrid sector). Workers in the hybrid structure perceive a higher coherence in their behavior with their coworkers. Broadly speaking, organizations in the hybrid sector link employees’ behavior to specific social initiatives, the aims of which are shared by workers. Public organizations describe that collective behavior is usually coherent with individual behavior (48.15 percent).

Figure 2

Do you think your behavior is coherent with that of your co-workers? (%)

Source: Authors

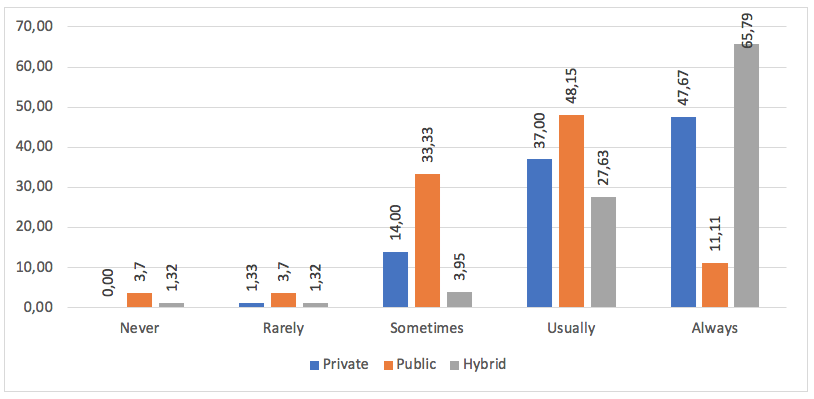

Finally, resemblance is analyzed according to the influence the organization has in shaping employees’ beliefs, values, and behavior. Therefore, it refers to how the worker assimilates with the corporate philosophy. A total of 52.11 percent of workers concede that values and personal beliefs were always inspired by the organization as they spend the majority of their time in the organization.

The field research found that private firms and hybrid organizations have a higher degree of influence on employees than the public sector. 50.33 per cent of employees in the private sector said that the company always influences their values, beliefs, and behavior. The highest influence was registered from hybrid structures, where 73.68 per cent of workers answered that organizations always had an influence on them. However, public organizations exerted the lowest degree of influence on their employees’ values. 48.15 per cent of workers in the public sector answered that the entity usually has an influence on them.

Figure 3

Do you have beliefs or values inspired by the organization for which you work? (%)

Source: Authors

Status represents workers’ perception in terms of the organizational reputation for stakeholders. Status is analyzed based on two informal institutions: First, how proud employees are with the image that the organization projects in the community; second, status is found in the impact that the organization’s social prestige has on workers. The authors expect that higher status leads to both higher pride in the organization’s social prestige and an increased happiness in working for that organization.

First, status is significant as it contributes to how proud employees’ are with the image that the organization projects towards the stakeholders. Image is the perception that interest groups such as customers, suppliers, competitors, and distributors have about the organization. A positive image improves workers’ pride in that organization. 57.57 per cent of workers always feel pride in their corporate image. The status is ratified by employees, 34.99 per cent of whom answered that they usually feel proud of their organization’s image.

The answers highlight that employees in private firms have a higher level of pride than workers in public organizations and hybrid structures. 75 per cent of workers in private firms demonstrated that they always feel proud of their corporate image. The hybrid sector has an even higher share with 82.89 per cent of employees usually feeling proud of their corporate image. Finally, 59.26 per cent of workers in the public sector usually feel proud of their corporate image.

Broadly speaking, workers in private organizations feel the most pride, and organizations with hybrid structures have lower recognition by the public. Finally, public organizations usually only generate a slightly positive corporate image. The public frequently relate public administration to bureaucracy, corruption, poor client service, and mismanagement.

Figure 4

Are you proud of the image of the organization for which you work? (%)

Source: Authors

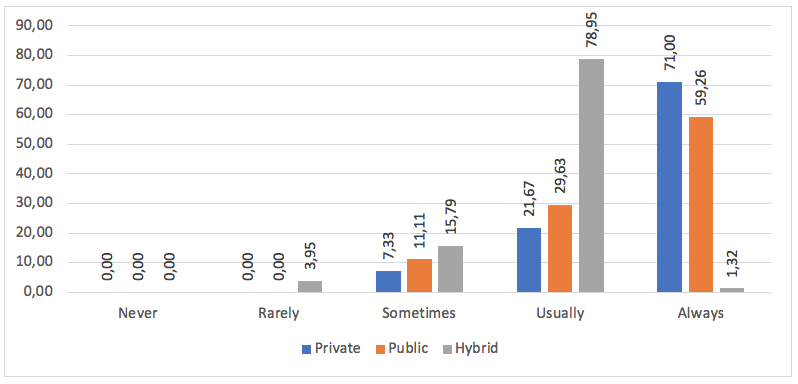

Additionally, status leads to higher level of employee internal identification. The impact that the social prestige of an organization has on employees refers to the workers’ perception of the public organizational reputation.

57.07 per cent of workers answered that they always perceive that the organization is socially prestigious. Furthermore, 33 per cent of employees, answered that they usually think the organization is prestigious. The above data describes workers’ positive perception of their organization.

Social prestige of the organization has a more profound impact on employees working in private organizations. 71 per cent of individuals, perceive that the organization is socially prestigious. 59.26 per cent of workers in the public sector confirmed that they always perceive their organizations to be socially prestigious. Finally, 78.95 per cent of individuals working for hybrid structures said that they usually perceive their organizations to be socially prestigious. Overall, organizations with a hybrid governance structure have a lower recognition level.

Figure 5

Do you think the organization at which you work is socially prestigious? (%)

Source: Authors

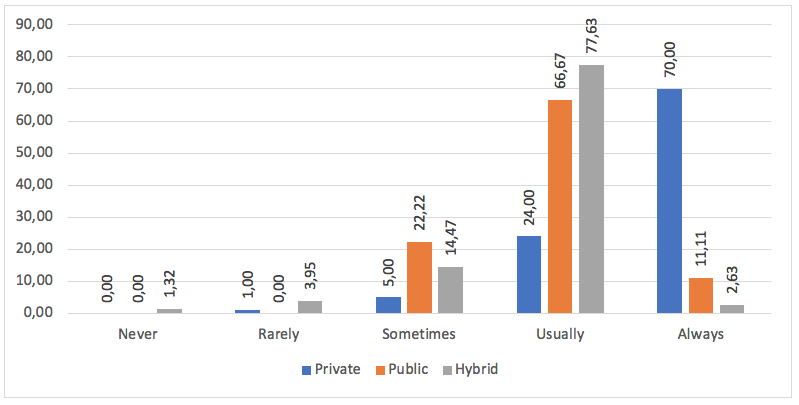

Labor satisfaction refers to workers’ emotional situation when undertaking labor tasks. It is developed from how contented employees are working with their coworkers. Finally, labor satisfaction comes from the compensation that workers receive for the effort they put into their jobs.

First, emotional situation refers to the motivation that workers have to undertake their labor tasks. Surveyed workers tend to describe having a positive emotional situation. 53.35 percent of employees always have a good attitude towards their work. Employees at private firms showed to have the most positive emotional situation. Up to 70 percent of workers in private organizations always have a good attitude in terms of going to work. Furthermore, 77.63 percent of employees in hybrid structures always have a positive feeling towards their work. Finally, 6.67 percent of workers in public administration usually have a positive emotional situation towards their work.

Figure 6

When you go to work, is your emotional situation positive? (%)

Source: Authors

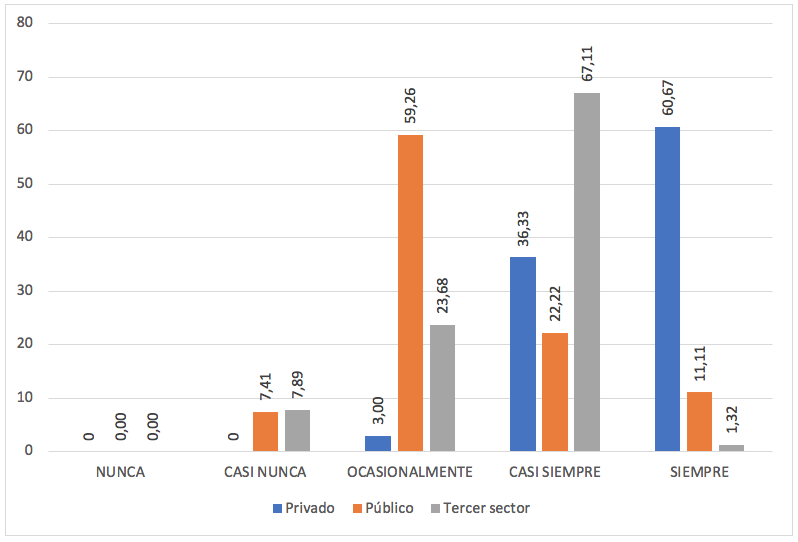

Second, how happy employees are with their colleagues reveals the motivation they have towards their work. 46.15 per cent of employees always feel happy with their coworkers; furthermore, 41.19 per cent of employees usually feel happy with their colleges. The individuals surveyed indicated having a positive organizational climate.

Workers in private firms were found to generally be happy: 60.67 per cent of individuals answered that they always feel happy with their coworkers. Also, 67.11 per cent of workers in hybrid structures answered that they usually feel happy with their coworkers. Finally, 59.26 per cent of public organization employees said that they sometimes feel happy with their coworkers. Overall, employees in private firms described being more motivated to work with their partners. However, team work in the public sector doesnot lead to particular satisfaction.

Figure 7

Are you contended with your co-workers? (%)

Source: Authors

Finally, how well workers are compensated by the organization improves labor satisfaction. 48.39 per cent of employees answered that their efforts for the organization are always compensated. Particularly, higher compensation is recognized by employees in private organizations, 64.33 per cent of whom consider that they are always well compensated. 67.11 per cent of employees in the hybrid sector usually feel well compensated for their work within the company. Finally, workers in the public organizations perceive that they are not as well compensated for their work. Approximately half of workers (48.15 per cent) rarely receive fair compensation for their efforts.

Figure 8

Do you think you have been compensated for your effort at work?

Source: Authors

In general, workers in hybrid organizations perceive their work environment to be of a lower status than workers in the private sector. Furthermore, workers in private organizations feel more satisfied with the compensation they receive for the effort they put into their jobs. Employees in public organizations perceive positive status; however, they have less internal identification.

Workers in private organizations have a more positive internal identification in the company in which they work than do employees in public sector and hybrid structures in terms of relating to corporate values, status of the organization, and labor satisfaction.

Employees in private firms claim to relate to their organizational culture. They feel that there is coherence between their behavior and that of their colleagues. Furthermore, workers in private organizations think that the firm in which they work inspires their belief systems, values, and behaviors. In addition, workers in private firms are proud of corporate image, and think that the company has social prestige. People working in market-oriented governance structures have a positive emotional situation when going to work. They think that efforts they put into their jobs are compensated for.

People working in hybrid structures go to work with positive attitudes to undertake their jobs. Workers in hybrid governance structures believe that their efforts are well rewarded; motivation improves productivity and allows organizations to fulfill their goals. However, employees in hybrid structures believe that their organizations are of a lower status.

Employees in public administration believe that their organizations are high status. However, they identify the least with the organization. In addition, workers in public organizations are the least satisfied and are the least contented in working with their colleagues.

Overall, employees in private firms and hybrid structures perceive that they have a stronger internal identification than employees in public organizations.

Capriotti, Paul (2009). Branding Corporativo: fundamentos para la gestión estratégica de la identidad corporativa. Santiago de Chile: EBS Consulting Group, 2009. p.145

Chamber of Commerce in Pereira (2017). Data base of organizations in Pereira. Internal reports.

Cifuentes, Álvaro; Cifuentes, Rosa María & Sabogal, Narciso (2001). Investigación de mercados. UNAD, p. 224

Coace, Ronald (1992). The institutional structure of production. In: The American Economic Review. American Economic Association, 82, 4, p. 713-719.

Cornelissen, Joep; Durand, Rodolphe; Fiss, Per; Lammers, John & Vaara, Eero (2015). Putting communication front and center in institutional theory and analysis. In: Academy of Management Review, 40 (1), p. 10-27.

Creswell, John W. (1994). Research Design: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Sage.

DANE – National Department of Statistics in Colombia (2017). Labor market: employment and unemployment. Retrieved in http://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/mercado-laboral/empleo-y-desempleo

Ebbinghaus, Bernhard (2006). When less is more: selection problems in Large-N and Small-N Cross national comparisons. In: International Sociology, 20,2, p 133-152

Furubotn, Erik & Richter, Rudolf (2005). Institutions and Economic theory: The contribution of the new institutional economics. The University of Michigan Press: Michigan.

Hodgson, Geoffrey (1993). Institutional economics: surveying the old and the new. In: Hodgson, Geoffrey (Ed.) The economics of institutions. Cambridge University Press: Aldershot. 50-77

Iacob, Constantin & Iacob, S (2016). The importance of institutional communication in the New Knowledge Economy. In: Valahian Journal of Economic Studies, 7, 3, p. 69-74

ILO – International Labour Organization (2017). Decent work. Retrieved in http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/decent-work/lang--en/index.htm

Kuhn, Timothy (2005). The institutionalization of Alta in organizational communication studies. In: Management Communication Quarterly, 18, 595–603.

Lammers, John & Barbour, Joshua (2006). An institutional theory of organizational communication. In Communication Theory, 16 (3), International Communication Association, p. 356-377.

Lammers, John (2011). How institutions communicate: institutional messages, institutional logics, and organizational communication. In: Management Communication Quarterly, 25 (1), p. 154-182

Menard, Claude (1997). Economía de las organizaciones. Bogota: Norma.

Menard, Claude (2004). The economics of hybrid organizations. In Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Institutions: Tübingen. 160, p. 345-376.

Menard, Claude & Shirley, Mary (2005). Handbook of New Institutional Economics. Springer: Netherlands.

North, Douglass (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press: New York.

Rogala, Anna & Bialowas, Sylwester (2016). Communication in organizational environments. Palgrave: London.

Topa, Gabriela & Morales, Francisco (2007). Identificación organizacional y ruptura de contrato psicológico: sus influencias sobre la satisfacción de los empleados. In: International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 7, 3, p. 365-379.

Van Knipenberg, Daan y Van Schie, Els (2000). Foci and Correlates of Organizational Identification. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73, p 137-147

Whetten, David & Albert, Stuart (2006). Revisited: Strengthening the Concept of Organizational Identity. In: Journal of Management Inquiry, 15, p. 220.

Williamson, Oliver (1996). The mechanisms of governance. Oxford University Press: New York.

Witting, Marjon (2006). Relations between organizational identity, identification and organizational objectives: an empirical study in municipalities. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 7, p 432-452.

WB - World Bank (2017). Doing business subnational report – Colombia. Retrieved in http://espanol.doingbusiness.org/reports/subnational-reports/colombia

1. MBA at Universidad de los Andes (Colombia). Researcher of Universidad Libre de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Administrativas y Contables, Grupo de Investigación Administración en las Industrias y Organizaciones. mail: anam.barrerar@unilibre.edu.co

2. PhD candidate in Resource Economics at Technical University of Munich – TUM (Germany). Researcher at Universidad Libre de Colombia, Facultad de Ciencias Económicas, Administrativas y Contables, Grupo de Investigación Administración en las Industrias y Organizaciones. mail: orlando.rodriguezg@unilibre.edu.co