Vol. 39 (Number 30) Year 2018. Page 24

Vol. 39 (Number 30) Year 2018. Page 24

Bekzhigit K. SERDALI 1; , Aliya T. BELDIBEKOVA 2; Rimma S. ZHAXYLYKBAEVA 3; , Gulnar UZBEKOVA 4; , Kudaibergen TURSYN 5

Received: 04/04/2018 • Approved: 22/05/2018

2. Media Literacy as Essential Category

5. Dysfunction of media literacy in the social contact environment

ABSTRACT: The paper defines the possibilities of democratization of the state at solving the problem of interaction with the modern information environment. The media environment, which forms the democratic principles governing the existence of a society, is represented by a sphere that not only requires significant attention on the part of the state and other market participants, but also proposes requirements to the structure of its application on the part of the consumers of the content. In this regard, the authors suggest investigating the issue of a possibility of teaching a person to handle with media environment. The education not only considers the practical skills of work with the sources of information environments, but also forms an opportunity of their practical application in social interaction. At the level of social development it is expressed in working out a social agenda, which is practiced as not only the source of change in social and economic conditions, but also allows changing the political conditions of functioning. Each participant of such a process has an opportunity for holistic understanding of possible correlation between personal freedom and the ability of handling with the information environment. The authors show that such an acceptance contributes to development of social environment and social formation in general as well as of the scientific structures in particular. |

RESUMEN: Este estudio define las posibilidades de democratización del estado para resolver el problema de la interacción con el entorno de la información moderna. El entorno mediático, que conforma los principios democráticos que gobiernan la existencia de una sociedad, está representado por una esfera que no solo requiere una atención significativa por parte del estado y otros participantes del mercado, sino que también propone requisitos para la estructura de su aplicación en el parte de los consumidores del contenido. En este sentido, los autores sugieren investigar el tema de la posibilidad de enseñar a una persona a manejar el entorno de los medios. La educación no solo considera las habilidades prácticas de trabajo con las fuentes de los entornos de información, sino que también constituye una oportunidad para su aplicación práctica en la interacción social. En el nivel del desarrollo social se expresa en la elaboración de una agenda social, que se practica no solo como la fuente del cambio en las condiciones sociales y económicas, sino que también permite cambiar las condiciones políticas de funcionamiento. Cada participante de dicho proceso tiene la oportunidad de comprender holísticamente la posible correlación entre la libertad personal y la capacidad de manejo con el entorno de la información. Los autores muestran que tal aceptación contribuye al desarrollo del entorno social y la formación social en general, así como de las estructuras científicas en particular. Palabras clave: desarrollo social, proceso democrático, educación de medios, población, entorno de información. |

UNESCO played an important role in formation and development of media education. It is believed that term “media education” was coined in 1973 at the joint meeting of the UNESCO Information Sector and the International Film and Television Council (Farnen & Meloen, 2000).

There has not been a unified theory of media education in the world. Analysis of eight theories shows that they have been undoubtedly originated from the relevant theories of mass communication.

Ideological Theory of Media Education. Its advocates believe that mass media manipulate the public opinion, particularly in the interest of particular classes, races and nations (Medvedeva, 2014; Rogach, 2014; Rogach et al., 2017). Children’s audience is the easiest target for the mass media influence. Therefore the main goal of media education is to encourage the audience to change the system of mass communication (in case if it is a democracy) or vice versa, to convince that mass media system is the most perfect (in case of authoritarian regime). It has been affirmed that in the 60s – first half of the 80s it existed in two variants: Western and Eastern-European. So, the focus was laid on the critical analysis, social and economic aspects of the countries’ media texts, particularly the critical approach was actively applied to the analysis of the mass media materials of the enemy camp. Today, the ideological theory has partially lost its positions, while the class approach has been replaced by the national and regional as well as social and political approaches. It means, the Third World countries try to defend themselves from the American mass culture (Orlowski, 2012; Hasanov, 2016; Eugstera & Hasanov, 2016).

Protectionistic (Injection, Defensive, Slit) Theory of Media Education. This theory is also called protectionistic (protection from harmful influence of mass media), theory of civil defense (the same), theory of cultural values (which are opposed to the values of media content). The name and description show that it is based on the theory of globe. According to its advocates, mass media have a large negative impact on the audience. Particularly, children take the violence depicted on the screen as a behavior pattern to use it in the real life. The audience here is a complex of passive consumers not capable of understanding the essence of media notifications (Gündoğdu & Yıldırım, 2010). The purpose of media education is smoothing the negative effect of involvement into the media. Teachers show the difference between the real and virtual life, and confront negative media content. The focus is laid on the problem of depicting violence and sexism on the screen.

The third theory of media education is the theory of media education as a source for satisfaction of the audience’s needs. Already from the name one may conclude that the main ideas of it are the ideas of assessment according to the theory of benefit and pleasure (as reasons of the audience applying to mass media). It admits that influence of mass media on the audience is limited, and the students may choose and assess the media text by themselves, according to their own needs (Fortunato, 2017). Thus, the goal of media education is to help the students to use media with maximum effect.

The fourth theory is called the practical theory of media education. Another name is “Media Education as ‘Multiplication Table’” (that is the same automatic skill to work with media as to calculate using the multiplication table). The influence of media on the audience is also admitted to be limited, while the main task is to teach the schoolchildren to use media equipment (Biesta, 2009). It means the focus is laid on learning the technical peculiarities of the party’s equipment and teaching to use the devices, including for creation of one’s own media content. It results in creating hobby groups of camera operators, photographers, computer programmers etc.

Aesthetic (Artistic) Theory of Media Education. Its origin is apparently connected with the cultural theory of mass communication. The purpose of media education is to help the audience in understanding of the basic laws and language of media as a kind of art, to develop aesthetic perception, taste and ability to conduct a qualified analysis of media texts. Therefore the essence of media education is concluded in studying the language of media culture, its history and the creator’s world. The students are taught to critical analysis of artistic media texts, their interpretation and qualified assessment (Glaeser et al., 2007). The artistic theory of media education is discriminatory due to the fact that it claims its goal to be development of ability to qualified judgement only in respect to the specter of art in media information (Brock-Utne, 2014). The issue of assessment of the media text quality should not be central in media education. While the main goal is to help in understanding of the mechanism of functioning the media, whose interests they defend, how the content of media texts reflect the reality, and how it is perceived by the audience.

Semiotic Theory of Media Education. It is certainly based on the works by structuralists. Media teachers of this area say that mass media often try to conceal the symbolic nature of their texts. Thus, the role of media education is to help passive audience to read the mass media texts correctly (Orlowski, 2012). The essence of the education become codes and “grammar” of the media text that is the media language and the strategy is teaching the rules of decoding the media text, description of its content, association, peculiarities of the language etc. Therewith the symbolic nature is peculiar to any subjects having the circulation, for example, tourist guides, and magazines covers. “Opaqueness” of text is also explained by the fact that media do not reflect the reality, but represent it.

The seventh theory of media education is represented as a means of developing critical thinking. Mass media here are represented as the fourth power which may dictate priorities (agenda) for the audience (Arthur, 2016). The goal of media education is protection of audience from manipulating influence of mass media, and teaching to guidance in the media flow. The teacher learns the mass media influence on individuals through codes (symbols), develops critical thinking regarding the media materials. It is believed that the audience in the conditions of information overload requires guidance, it should be taught to perceive and analyze the information, and also have an idea of the mechanisms and consequences of media influence (Garrison et al., 2012). The students should distinguish one-legged or corrupted information (especially on the TV, because it is deemed to be greatly influential). They should:

– find the difference between common facts and those requiring to be checked;

– define the reliability of an information source;

– define acceptable and inacceptable statements;

– find the difference between the main and peripheral information;

– distinguish bias of statements;

– find proofless arguments;

– distinguish logical inconsistency etc.

Thus the immunity to the lack of proofs, understatements and deception is being produced. As a result, a personality is being developed, who is ready to perceive the information of the mass media, capable of fully understand and analyze it as well as resist to the manipulative influence.

The eighth is the cultural theory of media education. Its advocates consider mass media offering but not obtruding the interpretation of the texts (Oelkers, 2000). The audience is always in the process of dialogue with the media notifications and their evaluation. The audience independently analyzes the content and interprets it in its own way. The main goal of media education is to help to understand how the media may enrich the perception, knowledge etc.

We should group the theories of media education. Defensive: injection, ideological, and aesthetic. In all these cases the teachers should try to protect from the harmful influence of the mass media. The opponents of these approaches say that they do not consider the tastes and needs of the society. The analytical theories: theory of critical thinking, semiotic and cultural theories (Skovsmose, 1994). In general one may conclude that in the concepts of the media education the prevalent are educational, teaching and creative approaches to the application of the media opportunities. We highlight the following typical stages of these theories:

1) acquiring the knowledge about history culture language and the theory of media (educational component);

2) development of perception of media texts, understanding their language, activation of imagination, visual memory, development of various kinds of thinking (including creative, logical, critical, visual and intuitive), the skills of deliberate understanding of ideas (moral, philosophical problems etc), images and so on;

3) development of creative practical skills on the media materials.

All these stages should be represented as a complex, otherwise media education is unilateral.

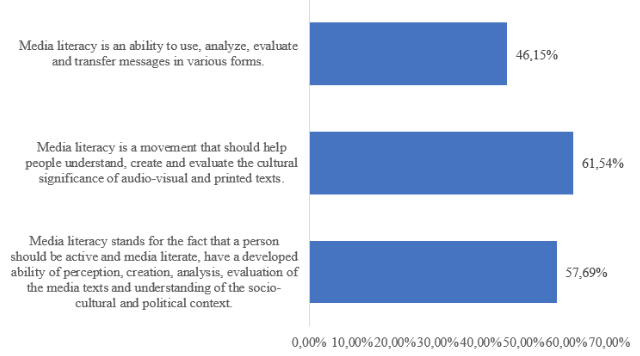

Usual three variants of answers are practiced in the media literacy discipline. We have obtained the distribution of the answers based on the question asked in a segment of the internet named the anonymous poll portal. The first one: Media literacy stands for the fact that a person should be active and media literate, have a developed ability of perception, creation, analysis, evaluation of the media texts and understanding of the socio-cultural and political context of functioning the media in the modern world, code and representative systems used by the media; the life of such a person in the society and in the world is connected with civil responsibility. Such a position got 57.69% votes. The second one: Media literacy is a movement that should help people understand, create and evaluate the cultural significance of audio-visual and printed texts. A media literate individual (and every person should have an opportunity to become this individual) is capable of analyzing, evaluating and creating printed and electronic media texts – 61.54% votes. The third variant of answer: Media literacy is an ability to use, analyze, evaluate and transfer messages in various forms – 46.15% votes. As we see, there is no clear leader, and the voted have been distributed approximately evenly (Fig. 1.).

Figure 1

Distribution of votes regarding understanding media literacy

It was found that media education implies (Davies, 2008):

– application of mass media on integrates cross-curriculum basis of the plan;

– consideration of mass media in the context of a certain discipline;

– development of critical understanding of mass media through the analytical and practical work;

– studying the forms, conventions and technologies;

– studying the media agencies, their social, political and cultural roles;

– experience of work with mass media, its comparison with the problems of one’s own life;

– research activities;

– borrowings from the audio-visual products, influence of the English language and the American art.

Media literacy is based on (Fortunato & Panizza, 2015):

– realization of media influence on personality and society;

– realization of the process of mass communication;

– abilities to analyze and discuss media texts;

– understanding of the media context;

– ability to create and analyze media texts;

– traditional and non-traditional literacy skills;

– pleasure, understanding and evaluation of the media text context.

We highlight the following goals of media education and media literacy (in order of descending the significance):

– to the develop the ability of critical thinking and critical autonomy of a personality;

– to improve the ability of perception, evaluation, understanding, and analysis of media texts;

– to prepare people for living in the democratic society;

– to develop the knowledge of social, cultural, political and economic meanings and subtexts of media notifications;

– to teach to decode the messages;

– to develop communicative abilities of a personality;

– to improve the ability of aesthetic perception, evaluation, understanding of media texts, of evaluation of the aesthetic qualities of media texts;

– to teach people to express themselves via mas media;

– to teach a person to identify, interpret and experiment with various kinds of technical application of mass media, to create media products;

– to provide the knowledge on the theory of mass media and media culture;

– to teach to the history of media and media culture.

There is a distinct line that the majority of the researches are advocates of the paradigm of teaching a person to critical thinking and being autonomous from the mass media. We suggest eight principles of media literacy, which provide an opportunity of better learning the media products:

1. Any media product is a designed reality. It reflects not a real world, but some subjective and thoroughly selected idea of it. Media literacy provides an opportunity to destroy such artificial structures and to understand the principles of their creation.

2. Mass media construct the reality. It is exactly mass media that form the majority of ideas of the environment and personal attitude towards what is going on. The attitude to the real world objects is formed on the basis of media notifications, which, in their turn, are constructed by the specialists with particular communicative goals. Mass media to some extent form our sense of reality.

3. The receivers of a media notification interpret its meaning. Mass media provide its audience with the information that lays the basis for the idea of the reality. Receivers of the message interpret and assign a meaning based on their own experience and such individual characteristics as personal demands and expectations, relevant problems, formed national and gender stereotypes, social and cultural experience etc.

4. Mass media have a financial support. Media literacy provides ideas of the fact – who supports any kind of mass media from the commercial perspective and how commercial background influences the content of mass product and its quality. Creation of a media product is, first of all, business that should be profitable. Any media business is based on particular people with their interests, and exactly these interests define the content of what the receiver of a media notification watches, reads, and listens to.

5. Any media notification translates the ideology and information of particular values. Any media product is a kind of promotion of a life style or any other values. Directly or indirectly mass media create an image of a “good” life in the opinion of the audience; they form consumer tastes and provide an idea of general ideological position.

6. Mass media perform special and political functions. Mass media influence the political situation and provoke social changes. Television influences the results of an election. The electorate people substantiate their decisions on the basis of their ideas of the candidates, i.e. on the basis of the formed image. Media make us think about the events taking place in the other countries.

7. Content of the message depends on the kind of mass media. Different media deliver the message of an event accentuating its different aspects. Thus, the audience has an opportunity to get acquainted with different perspectives and to for its own position.

8. Every media resource has its own unique aesthetic form. Every media product should be represented to the audience in the aesthetical form, which provides an opportunity to a certain extent to enjoy the form and the content.

In the context of the modern discourse on the point of the Kazakhstan media education there is a still subtle shift appeared towards the media education policy. This phenomenon is rather positive, but at distortion of the meaning media education may have negative consequences (Davies, 2008).

The notion of ‘politicy’ itself (from Greek “politika”) is interpreted by dictionaries as the art of managing the state and society, or as a complex of social ideas and the purposeful activities preconditioned by them, connected with formation of the relationship between states, peoples, nations, and social groups. Various kinds of policies are known – domestic, foreign, economic, social, cultural, and educational.

Media educational policy is preconditioned by the world trends in development of society, such as cutting-edge information technologies, embracing the entire world, new models of personal media behavior, and global quasi-reality. However, media educational policy also has quite distinct specific national peculiarities (Davies, 2008).

It is enough just to take a look at the history of development of the Kazakhstan media education in order to note the consequence of the change in the attitude to the institution of media education, influenced by the political cataclysms of the Kazakhstan state in the 20th century. This universal instrument of influence on the young generation was tailored to the details and mechanisms of the Soviet propaganda machine. If in the years of repressions many initiatives of media education were eliminated, and it left the arena of the Kazakhstan science and practice for long, then in the 1960s, there vice versa was the media educational “thaw”, and the research in this sphere began: various media educational projects were being developed.

The next stage of rethinking of media educational experience was marked alongside with perestroika, in the 1990s, when a wave of innovations rushed into the schools and the adult education centers. It contributed to development of the Kazakhstan media education. It was the exact time when various experimental sites started to emerge, where the modern models of media education were worked out. It was the time when many successful media educational projects were born and strengthened, which still exist (Asrak-Hasdemir, 2012).

In the period of sharp rise in political activity of the population, the growth of the civil self-identity, the civil approach towards media education becomes relevant. The course for modernization was impossible without media competent personality having full information about the current events, which is able to evaluate, interpret it and to clearly express his or her opinion.

However, some initiatives of the modern officials based on the defensive theory of media education, by means of which the attempts are taken to protect children and adults from “harmful information”, to forbid undesirable content, to close the access to the information, transfer real social activity to the virtual one, evidence that the Kazakhstan media education is coming into a challenging period.

Moreover, today the practice of substitution of media education by the technologies of information policy, PR, use of media educational experience for the purposes of promotion of necessary ideas, formation of the image of particular leaders, companies and state institutions (Giroux, 2006).

Such a complicated development trajectory of the Kazakhstan media education shows that here we are dealing with a rather politicized instrument, which in different periods serves different goals quite successfully.

Probably, exactly the lack of a clear goal explains the lack of explicit success in promotion of media education in recent years. Much has been done. The Kazakhstan science has undergone a significant breakthrough in the theoretical comprehension of the media education processes; dozens and hundreds of scientists joined the work on acquisition of the modern technologies and methods. However, activities of particular enthusiasts have not become systematic as it is, for example, in Canada, USA, Germany, France, Finland, Australia, Hungary, Czech Republic, Serbia and many other countries, where media education has been included into the national curricular (Glassman, 1997).

Certainly, the experience of application of the models that showed good results in some specific conditions is not to be borrowed hastily. According to Professor Yehezkel Dror, consultant of Department for Development Support and Management Services of the United Nations Secretariat, “the same model of policy development suits for most of the states, provided that their governments are primarily focused on administrative and technical, rather than political aspects.”

Efficiency of media educational policy depends on reasonability and feasibility of the set tasks. The examples of the politicized youth projects, such as “Information Flow” nearby Seliger Lake or “Civilization” by Mikhail Khodorkovsky evidence a rather productive use of media educational technologies by political parties and movements. If we speak about the humanistic ideas, strengthening the national traditions and openness to new, then the leaders in formation of these basics of personality should be socially responsible government, mass media and social institutions.

The goal of media education is a cornerstone capable of breaking the best methods. It should coincide with the social ideas of ideals and values.

Depending on the goal, there will be different means of its achievement. If the goal of media education becomes formation and development of the society of free thinking citizens, then the means will include the whole range of social assets that will be manifested through integration, dialogue, critical thinking and civil contract.

However, media education may happen to be, as it often happens, a servant of other goals, particularly, creation of the person manipulated, uncritical, and mesmerized by stereotypes. In this case the media educational technologies become the technologies of propaganda, manipulation, and information influence. As this is described by the documents of the Council of Europe, “free and independent media are a real force in promotion of democratic changes, while in the hands of the totalitarian powers they may become the means of incitement of ethnic hatred and indoctrination of negative stereotypes” (Hera & Szeger, 2015).

If at the use of media educational technologies media business starts to dominate, then the audience as the subject of media education will also be considered exclusively as a source of profit. Citizens turn into users, while media educational technologies become the media technologies for capitalization of human instincts.

At development of media educational policy presence of a manipulative type of educational strategies cannot be excluded, because the population is in the sphere of influence of various political, ideological and financial structures with their own tasks and interests. Therewith, it is important always to remember, that in the true sense media education may develop only in a free democratic state where there is freedom of access to information and self-expression, the society controls the power and the current political processes, where civil institutions are developed and people have high level of media informational literacy.

In the modern world social interactions are increasingly mediated by technical means and inevitably acquire the characteristics preconditioned by these technologies. So, particularly, communication technologies make their impact on social and political processes provoking new mechanisms of mass mobilization. Among the diversity of these new technologized information and communication systems the attention is taken by social media playing an increasingly important role in the political and socio-cultural processes of our time (Hess & Wright, 2009).

A fairly common statement in political and journalistic discourse has become the one, that social media are “killers of authoritarian regimes”, i.e. the mechanism of democratization of political system from below. At the same time a series of empirical examples, such as the Iranian Twitter-Revolution, the Egyptian Facebook-Protests and, finally, the protests in former USSR have not still become the basis for creation of the sociological methodology, theory and methods of empirical study of social media as the mechanisms of mass mobilization prior to the protest political participation.

The goal of the section and respectively the practical part are revealing of the peculiarities of functioning the mobilization mechanism of social media with the focus on the protest forms of political participation. In the frameworks of this section we, first of all, are going to distinguish the traditional and social media considering the mechanisms of mass mobilization; to analyze the prerequisites of relevance of this problematics for the modern society; to consider the peculiarities of social interpretation of conventional and non-conventional political participation and to represent the results of the empirical study of social media mobilization influence on the citizens’ protest sentiments (Zajda, 2013).

When distinguishing the traditional and social media we base on the idea of the fact that traditionally the communication process is described in terms of transition of information as a process uniting the one who sends information (sender) and the one, who receives it. Thus, media are only the means of establishing the connection and represent the interest only to the extent, to what they contribute to or prevent from establishing such a connection. From this perspective traditional media are those establishing a unilateral connection: TV, radio, printed media, while social are those establishing interconnection (bilateral connection). Besides the bilateral connection the notion of “social media” points out at the kind of mass communication, implemented indirectly through the Internet and has a series of significant differences from the traditional means of mass communication (Biseth, 2009). So, let us consider the differences between the traditional and social media:

1. Quality. The traditional and modern social media differ by reliability, themes and the way of representation of the information. For the traditional media the quality standards are set and controlled by an entire complex of formal and informal rules (laws on mass media, standards of copyright and taxation). While social media contain both the segment of high quality information content and a large segment of low and dubious quality.

2. Producers of content. Both the traditional and modern social media are available without limitation thanks to technical opportunities. At the same time they differ by the degree of centralization and hierarchy (every user may produce content in the environment of the modern social media, while the traditional media produce the one, “dictated” by the owners and the editorial policy of the information agencies and editions).

3. Availability and Media Outreach. The traditional mass media do not require of a user to have special resources or knowledge on the technology of informational distribution, while social media require of a user to have computer knowledge and skills (or to be familiar with any other multi-media devices, and the internet is still not wide-spread in some societies at the level of traditional media).

4. Dynamism. Traditional mass media – TV or printed media compared to social media significantly fall short of promptness, because, for example, thanks to such internet service as Twitter, each its user may almost immediately share the information in the internet using even only a portable pocket device.

5. Mobility in Production of Artifacts. Traditional media, having once published particular information, are not capable of changing it and are responsible (including legally) for the publicized content. While the modern social media are mobile in this sense, less reliable, and significantly less responsible both ethically and legally (Korovin & Smeshkova, 2017).

New information and communication technologies, especially the internet, have totally changed the visible environment of the collective action. Peculiarities of social media as a mechanism of mass mobilization to political participation are out of content. In particular, social media as mechanism for political mobilization may be used by both the oppositionists-democrats, adversaries of totalitarianism or corruption, and radical antidemocratic powers or terroristic groups. Therefore we should remember about the problematic, dysfunctional aspect of this mechanism (Table 1).

Table 1

Functional and dysfunctional aspects of operation of social

media as a mechanism for political mobilization

Functional Aspects |

Dysfunctional Aspects |

Social media mobilize to collective action and political participation without any geographical limitations |

Social media transfer communication to the virtual environment which inevitable causes deficiency or lack of personal communication between the members of the mobilized group and generally exclusively online political participation, which significantly impoverishes the armory of political actions and their efficiency |

Social media build horizontal non-hierarchical and nom-centralized connections and may limit the domination of the vertical networks (financial industrial groups, party and power circles etc.). Thus, social media oppose the authoritarian vertical directive mobilization and contribute to spontaneous horizontal mobilization |

Social media do not create alternative dimension of reality, but otherwise, they reproduce the reality in the virtual dimension. Thus, mass mobilization by means of social media reproduces social divisions, particularly the structures of social inequality and social barriers, existing in real life |

Social media have an ability to mobilize to political participation regardless of adherence to traditional societies. Forming so-called crosscutting ties, which allow mobilization to happen out of exclusive principles, overcoming narrow ethnic, confessional, racial and ideological borders |

The user shelled by social media acts with a jaundiced eye, according to his or her political views, values and affiliations. Accordingly, social media reproduce all the particular divisions existing in social reality |

Social media contribute to the problem-focused mobilization, rather than to ideological or program-defined, that’s why they are closer to the needs of regular citizens, rather than to the “big-league” politics |

|

Social media contribute to formation of dynamic, maneuverable structures. In the conditions of protest policy such structures are easier to avoid reprisals by the authorities (particularly, due to the technical peculiarities of using the internet: change of profiles, anonymity, change of IP addresses etc.) |

Lack of single ideology, principles or program of actions leads to internal discussions, instability of the formed structures, and lack of common ethics of political participation |

Optimistic interpretation of functioning social media acknowledges in this mechanism a significant potential of transformation from one of the concurrent factors of formation of civil societies to their important component, especially in the countries at the stage of democracy-building. In such countries civil society is being originated in the fight for its interests before the authoritarian or totalitarian regimes. The internet serves a means of direct communication between the citizens and the power, which results in minimization of dependency of the citizens on the representatives, elected party organizations and the groups of interests.

One of the problems of formation of civil society is a traditionally authoritarian way of functioning of the power structures and lack of confidence in the power institutions in the society. A problem of establishment of civil society is post-communist traditional skeptical attitude towards any organizations, traditional regime of closure of political power, low level of social involvement into making political decisions and confidence in mass media, political-administrative spheres, and corruption.

Social media may be applied for recovery and formation of confidence, imposition of requirements of the governmental authorities’ action transparency and consideration of the needs of various social groups in the process of formulation and making political decisions and mainly for raising public awareness with the manifestations of corruption and for fighting against misuse of power at all the levels. These opportunities are based on social protest against violation of the basic human rights, which may be clearly formulated and directed at particular persons or specific social institutions by means of social media, and implies the growth in the degree of social solidarity.

At the same time there is a series of dilemmas connected with the mobilizing function of social media, because, on one hand, strengthening of political spontaneous activity and control over civil society over the authorities causes formation of a well-organized, embedded democratic society, and on the other hand, it may create barriers, restraining functioning of the power structures, in accordance with the formula “strong society – weak state”.

In the newly emerged and democratic states the main collision centers around performance of the government authorities in the conditions of growing control on the part of civil society, because the goals of politicians and public may not be the same. In young democracies mass political mobilization may significantly weaken the stability and performance of political and administrative institutions by pressing them. The growth of the civil activity and people’s aspiration to acquisition of real subjectivity, opportunity to influence making political and administrative decisions becomes the challenge for the entire political system, especially in case of non-conventional forms of political participation.

One of the key issues of conceptualization to mobilization of political participation is distinguishing between conventional and non-conventional political participation. Protest behavior may take on two forms: a protest, if the opposition’s addresses have the goal of changing the structure of government, it stands for radical reorganization of the political system and require to admit their subjectivity in the political process or the pressure, if the opposition group initiating the protest addresses, is considered by the political government of the state as a legitimate member of the political system.

The last definition underlines the importance of phenomenon of the political opportunities’ structure, i.e. legitimate means of influence on making political decisions and functioning of the political system in general. If there are such legitimate means, then the political participation takes on conventional forms, but if there are not – the only “valve” that allows blowing off social strain are protest actions with high destabilizing potential. So, when democracy is not fully-functional, and participation of citizens is reduced only to participation in elections, there is a void emerging in the structure of political opportunities, which is filled with non-formalized and non-conventional, in particular, forms of political participation.

In this regard we suggest a new instrument – index of destabilizing capacity of protest potential. This instrument allows revealing the degree of the respondents’ adherence to the forms of political participation, while they have different values of destabilizing capacity. Every protest action has its own coefficient of destabilizing capacity, calculated on the basis of experts’ evaluations. So, participation in elections does not destabilize the political system, participation in unauthorized meeting provokes certain destabilization, while seizure of state administrative buildings significantly destabilizes the political system. The integral index of destabilizing capacity of protest potential of a population is calculated as mean value of the sum total of protest actions, where people expressed their intention to participate, considering the index of destabilizing capacity of every action.

We, using the data base of an omnibus research (N = 397), are going to analyze a series of indicators characterizing the behavior of respondents shelled by social media, on one hand, and the forms of the respondents offline political participation, using the index of destabilizing capacity of protest potential, on the other hand. In the analysis of the data base we applied a complex of statistical methods (unidimensional, two-dimensional and correlation analysis). The data base is analyzed by using the SPSS software package.

First of all, let us clarify what percent of the respondents is covered by the internet and by social media in particular. Notably, due to a great number of social media – blogs, twitters, forums, and social networks – this percent of sampling will be almost the same. Being an internet user today is almost equal to being a user of social media: leaving comments on the internet content; posting the internet content, which may be evaluated by the other users; evaluating some or other content; getting familiar with online activities of the other users; communicating with them.

The obtained data show that over 70% of the respondents (N=280) are internet users. This group unsurprisingly differs to a significant extent from those who do not use the internet by the age indicator. The internet users are generally younger: average age of this group is 40 y.o., while for the group of respondents who do not use the internet – 59 y.o. Another differentiating structure in the aspect of the internet use is the level of income: poor people use the internet less than the others. Thus, the financial and economic poverty is accompanied by the informational poverty, producing lower level of life chances for vulnerable population layers.

We obtained the following data according to a series of indicators, describing the readiness for conventional and non-conventional forms of political participation. The indicators of membership for the three most popular “shells” of social media –social networks Odnoklassniki, Vkontakte, and Facebook – amount for 34%, 39.6% and 32.8% respectively.

The indicators of the destabilizing capacity index of protest potential pointed out at high significance of the mean values difference for the group of users of social media and the group of respondents, who uses exclusively traditional media. The relevant level is significantly higher for the users of social media and amounts for 4.81. Notably, protest potential may develop into mass actions, when the index exceeds 4.4 points. The values exceeding 4.4 points were noted at the following moments of the recent history: 1998 peak of the economic crisis; 1999 change of power, 2011 cases of dishonest tabulation of votes at the election (Table 2).

Table 2

Characteristics of the Citizens Using Social and Traditional

Media, Relevant to the Problematics of Political Participation

* Significant at level 0.05;

** Significant at level 0.01.

As we see, for users of social media the indicators are significantly higher that evidence the focus on both, traditional and non-conventional forms of political participation. It hypothetically points at high level of politicization of the respondents using social media and at their highest level of political subjectivity.

The characteristics of users of social media were revealed, and particularly, – of active users of social media pointing at the special role of this group in the political system of the modern society. To our mind, in this case it is reasonable to apply the approach proposed by the American scientist J. Rosenau, who calls voters at large a “mass public”, and in its context defines “considerate public” and “mobilized public”. Considerate public usually includes people with high level of IQ and education capable of looking into the politics independently and will not be an object of manipulation on the part of mass media. Mobilized public is the percent of population that may be organized for active participation in political life (meetings, demonstrations and various forms of pressure).

To our mind, in case of post-Soviet society we observe the phenomenon that may be called an “overheating” of the political system, when a long-term, perpetual and active participation of citizens in political issues leads to so-called “entry overwork” of political system and to invalidity of political institutions. While according to the observations of the Austrian scientist J.-H. Heinrich and the American scientist J. Rosenau active part in the political process is constantly taken by less than 15% of adult population (“considerate public”, also including professional politicians), in the post-USSR period from the beginning of the crisis in 2014 we note an explosive growth of interest to politics and political participation (including in the wide range of protest forms of political participation). So, among users of social media 37% use the internet on a daily basis for learning the social and political information. The same group of population is also notable for high indicators of destabilizing capacity of the protest potential (5.6 provided that the critical value pointing at the dangerous nature of mass protests is 4.4). Thus, we may suppose that exactly the most active users of social media are that “considerate public” following with insight the current political events and to the highest extent exposed to the protest political participation. This group is a kind of a locomotive of political protest. Average age of the respondents from this group is 35 y.o. There is an interconnection between self-positioning on the scale of ideological preferences and adherence to more destabilizing forms of political participation (respondents posing as more ‘right” are to a greater extent prone to such forms of participation).

On summing up we should note that in the documents of the international organizations media education is considered as acquisition of media-specific skills. The UNESCO specialists believe that the right to media education as part of rights to self-expression and information belongs to the basic human rights and freedoms. There is also a popular opinion that media education should be life-time.

An important role is played by understanding media as an autonomous education, towards which a person should play an active and independent role, not only not identifying him or herself with the media, but also taking a constant critical position towards them.

Some scientists believe that for effective media education the students should take part in creation of media products. Apparently it is believed that thus people will learn to consider journalism as practical exercise, rather than a sacred industry, and will consider the results of the journalists’ work with more criticism.

Scientists consider that media education is far cry not only from the education by means of media, but also from learning the media themselves. The goal of media education is considered to be achievement of media literacy.

The importance of media education in the modern world is caused by the fact that the mass media in the conditions of globalization and information society often decisively influence the way we perceive the world. But mass media are often irresponsible at their function to truthfully inform about the events and facts of reality. It means that virtual picture of the world often significantly differs from the real one. Media education provides a person with an opportunity of critical attitude towards the media messages.

The review of the media education theories has shown that they are of fragmental nature and not based on a coherent generalization of the modern experience in studying the mechanisms of mass media actions and achievement by them the effect, i.e. the influence on the audience. Besides, understanding the regularities of mass media functioning, the links where the information is being distorted is, to our mind, an obligatory component of effective media education (Perry, 2005).

First, the internet in general and social media in particular cover a significant part of population of the post-Soviet states, more and more becoming a routine for the citizens of different social and demographic categories. At the same time age and wealth status remain a differentiating factor pointing at reproduction of the phenomena of information poverty. Second, among the diversity of the spheres touched upon by social media, a significant one is social and political sphere. We have found the evidence supporting the fact that activities in social media are connected with the form of political participation of the respondents, – both in conventional (noted as membership in social organizations), and non-conditional dimension (through an integrated indicator – index of destabilizing capacity of protest potential). Third, a special concern is provoked by possible application of the mobilization potential of social media in connection with extremism. We have found that users of social media take statistically higher positions of focus on destabilizing forms of political behavior (we used index of destabilizing capacity of protest potential to check the hypothesis) compared to the respondents using only the traditional media. It suggest that social media are simultaneously connected with the phenomenon of “considerate public” – a group of population closely following the political process, having a relatively high level of political competence and focus on political participation both in conventional and non-conventional dimension. Fourth, the experience of the modern post-Soviet society points at rejection by the population masses of the formal institutional forms of mass mobilization and political participation, so political parties and social organization have not still become effective structures of collective actions, which is shown by relatively low indicators of membership in such structures over the years of independence of the former USSR states. Despite social media is a mobilization mechanism to the greatest extent corresponding to the modern society, they combine the elements compensating low sense of political subjectivity, flexibility and spontaneity, horizontal and voluntary nature (Carr, 2013).

The further research areas are connected with revealing the regularities of interconnection between the online and offline forms of political participation, as well as with the analysis of destabilizing activism, which is a significant trait of the modern society and particularly is manifested in such phenomenon as “stability only through political methods”. The last example of a destabilizing, non-conventional form of political participation represents a threat of degradation of the mobilizing mechanism of social media with the elements of increased civil control, which turns it into an element of contemporary ochlocracy (mob rule) of the electronic communications.

Arthur, C. (2016). Financial literacy education as a public pedagogy: Consumerizing economic insecurity, ethics and democracy. In C. Aprea, E. Wuttke, K. Breuer, N. K. Koh, P. Davies, B. Greimel-Fuhrmann, & J. S. Lopus (Eds.). International Handbook of Financial Literacy (pp. 113-125). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Asrak-Hasdemir, T. (2012). Fights over human rights: A strange story of citizenship and democracy education. In K. İnal & G. Akkaymak (Eds.), Neoliberal Transformation of Education in Turkey: Political and Ideological Analysis of Educational Reforms in the Age of the AKP (pp. 205-218). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Biesta, G. (2009). Sporadic democracy: Education, democracy, and the question of inclusion. In M. S. Katz, S. Verducci, & G. Biesta (Eds.), Education, Democracy, and the Moral Life (pp. 101-112). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Biseth, H. (2009). Multilingualism and education for democracy. International Review of Education, 55(1), 5-20.

Brock-Utne, B. (2014). Education, democracy and development – does education contribute to democratisation in developing countries? International Review of Education, 60(1), 145-147.

Carr, P. R. (2013). The mediatization of democracy, and the specter of critical media engagement. In L. Shultz & T. Kajner (Eds.), Engaged Scholarship: The Politics of Engagement and Disengagement (pp. 163-181). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Davies, L. (2008). Interruptive democracy in education. In J. Zajda, L. Davies, & S. Majhanovich (Eds.), Comparative and Global Pedagogies: Equity, Access and Democracy in Education (pp. 15-31). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Eugstera, N., Hasanov, E.L. (2016). Innovative Features of Comparative-Historical Research of European and Azerbaijani Cultural Heritage (Based on the Materials of British and Azerbaijani Literature of the XX Century). International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(15): 7495-7505.

Farnen, R. F., Meloen, J. D. (2000). Democracy, Authoritarianism and Education: A Cross-National Empirical Survey. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Fortunato, M. W. P. (2017). Advancing educational diversity: antifragility, standardization, democracy, and a multitude of education options. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 12(1), 177-187.

Fortunato, P., Panizza, U. (2015). Democracy, education and the quality of government. Journal of Economic Growth, 20(4), 333-363.

Garrison, J., Neubert, S., Reich, K. (2012). John Dewey’s Philosophy of Education: An Introduction and Recontextualization for Our Times. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Giroux, H. A. (2006). America on the Edge: Henry Giroux on Politics, Culture, and Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Glaeser, E. L., Ponzetto, G. A. M., Shleifer, A. (2007). Why does democracy need education? Journal of Economic Growth, 12(2), 77-99.

Glassman, R. M. (1997). The New Middle Class and Democracy in Global Perspective. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Gündoğdu, K., Yıldırım, A. (2010). Voices of home and school on democracy and human rights education at the primary level: A case study. Asia Pacific Education Review, 11(4), 525-532.

Hasanov, E.L. (2016). About Comparative Research of Poems “Treasury of Mysteries” and “Iskandername” on the Basis of Manuscript Sources as the Multiculturalism Samples. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(16): 9136-9143.

Hasanov, E.L. (2016). Innovative basis of research of technologic features of some craftsmanship traditions of Ganja (On the sample of carpets of XIX century). International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(14): 6704-6714.

Hera, G., Szeger, K. (2015). Education for democratic citizenship and social inclusion in a post-socialist democracy. In S. Majhanovich & R. Malet (Eds.), Building Democracy through Education on Diversity (pp. 41-56). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Hess, D. E., Wright, S. M. (2009). Teaching against threats to democracy: Inclusive pedagogies in democratic education. In S. Mitakidou, E. Tressou, B. B. Swadener & C. A. Grant (Eds.), Beyond Pedagogies of Exclusion in Diverse Childhood Contexts: Transnational Challenges (pp. 131-146). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Korovin, N.K., Smeshkova, L.V. (2017). Psycho physiological Examination: Procedural and Forensic Aspects. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 20(Special Issue 1): 1-7.

Medvedeva, N.V. (2014). State-public management of education: the essence and features of implementation. Materials of the Afanasiev Readings, 1: 182-185.

Oelkers, J. (2000). Democracy and education: About the future of a problem. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 19(1), 3-19.

Orlowski, P. (2012). Teaching About Hegemony: Race, Class and Democracy in the 21st Century. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Perry, L. B. (2005). Education for democracy: some basic definitions, concepts, and clarifications. In J. Zajda, K. Freeman, M. Geo-Jaja, S. Majhanovic, V. Rust, J. Zajda & R. Zajda (Eds.), International Handbook on Globalisation, Education and Policy Research: Global Pedagogies and Policies (pp. 685-692). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Rogach, O.V. (2014). Formation of the social order for educational services as the mechanism of social management. Materials of the Afanasiev Readings, 1: 188-193.

Rogach, O.V., Frolova, E.V., Medvedeva, N.V., Ryabova, T.M., Kozyrev, M.S. (2017). State and public management of education: Myth or reality. Espacios, 38(25): 15.

Skovsmose, O. (1994). Towards a Philosophy of Critical Mathematics Education. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Zajda, J. (2013). Educating for democracy: Background materials on democratic citizenship and human rights education for teachers. International Review of Education, 59(1), 131-132.

1. Department of Kazakh Philology and Journalism, A. Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University, Turkistan, Republic of Kazakhstan. E-mail: aksari@mail.ru

2. Department of Kazakh Philology and Journalism, A. Yassawi International Kazakh-Turkish University, Turkistan, Republic of Kazakhstan

3. Department of Journalism, Kazakh National University of Al-Farabi, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan

4. Department of Journalism, Kazakh National University of Al-Farabi, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan

5. Department of Social Sciences, Suleyman Demirel University, Almaty, Republic of Kazakhstan