Vol. 39 (# 03) Year 2018. Page 6

Ángela Julieta MORA Ramírez 1; Eduardo Norman ACEVEDO 2

Received: 05/09/2017 • Approved: 25/09/2017

ABSTRACT: This study examines the process of internationalization of the SME enterprise in the footwear and manufacturing cluster of Bogota. The method used is systematic review of the literature (SRL), which identifies key components, and is now even more necessary given the external dynamics of bilateral and multilateral treaties and agreements. It includes a specific analysis of the sector in Bogota and, through its findings, seeks to reclaim the productive processes and skilled labor force in homogeneous conditions of support. |

RESUMEN: Este estudio examina el proceso de internacionalización de una empresa PYME en el grupo de calzado y fabricación de Bogotá. El método utilizado es la Rrevisión Sistemática de la Literatura (RSL), que identifica componentes clave, y que ahora es aún más necesario dada la dinámica externa de los tratados y acuerdos bilaterales y multilaterales. Incluye un análisis específico del sector en Bogotá y, a través de sus hallazgos, busca reivindicar los procesos productivos y la mano de obra calificada en condiciones homogéneas de apoyo. |

Economic development currently requires solid economies strengthened by their state apparatus, large businesses, and, obviously, the activities of the small enterprises which exercise such an important role in the economies of our countries.

The internationalization of the economy and growth in the open market system have generated much discussion and investigation. This article explores the description of the current focus in the theory of internationalization and its effect on the SME, including both a description of the importance of business clusters and a description of the present situation of the sector in the city of Bogota (Colombia).

The article was elaborated upon using a systematic search for literature based on the SRL protocol proposed by Kitchenham (2004), who proposes an evaluation of the current literature by the application of a revision method which allows the process to be repeated in the future. The use of this tool in the current study is seen as an opportunity to compile the extant information regarding the internationalization of SMEs in a rigorous and impartial manner, for the purpose of arriving at conclusions which are broader than those of the individual studies or as a means of approximating future research activity.

It is necessary to maintain a record of the procedure used by creating a database of the data obtained from the search equations used for this review for the purpose of ensuring results which are both homogeneous and conclusive. The protocol appropriate for the study includes 13 activities categorized under the planning, execution, and reporting stages according to their objectives. The needs and questions are formulated during the first stage (planning), during which the manner in which the collected information will be presented is also planned (Lopez, Mendez, Paz, & Arboleda, 2016).

Search equation used in Scopus:

TITLE-ABS-KEY (internationalization AND of AND smes) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR , 2016) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR , 2015) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR , 2014) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR , 2013) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR , 2012) OR LIMIT-TO (PUBYEAR , 2011)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE , "ar")) AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA , "BUSI") OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA , "ECON") OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA , "SOCI")))

The search generated a result containing 342 documents over a 6-year period, long enough to form a general outline of the information gathered from the sources during the collection process and to dispel doubts that might otherwise arise concerning the process used for the bibliographic review. This equation indicates the manner in which both official and unofficial sources are selected and reviewed. During the planning stage, it is necessary to identify the specific goal and explain why it is important, in addition to drafting the specific objectives. In order to determine the strategy to be used, all points must be taken into consideration and pertinent search strings must be elaborated in order to obtain the articles required for SRL (Petersen, Feldt, Mujtaba, & Mattsson, 2008). The search strings are formed as determined by a database containing both filter criteria and inclusion/exclusion criteria.

In this context, the role of the researchers is that of mere observers of the phenomenon, their only contribution being a report of their findings.

In the literature, the activity of the SME is found to be evolving and variable (TURNBULL, 1987). According to some authors such as Wind, Douglas, and Perlmutter (1987), these characteristics are derived from experience and are a result of an orderly process involving the will of the organization, an idea affirmed by Bilkey andTesar (1977), Cavusgil (1980), and Reid (1982).

The process of internationalizing an enterprise is highly complex, due especially to the factors of competition, the development of policies resulting in the curtailment of relationships, and the success in the rest of the world (GALÁN, GALENDE, & GONZÁLEZ, 2000), as well as the position of an enterprise with reference to current global economic development, monopoly, and the massification of the unique characteristics of current global consumers as a result of communications technologies.

Other authors such as Calof and Beamish (1995) understand internationalization to be a spontaneous process involving the application of processes in a different environment. Accordingly, Melin (1992) sees it as a strategic process for the majority of SMEs.

In this respect, it becomes necessary to examine several variables. “Crossing the boundaries which exist between economy and society, between interior and exterior environments of the company, between a company and its networks, and between companies and territories. Thus, the territory is a strategic variable for company development, together with project analysis, markets, and technology” (Lazzeretti, 2006, pag. 19).

For Vazquez (2009), it is clear that policies governing development are related to innovation and current trends, resulting in the modification of a product according to the local market needs, a fact which must be taken into consideration when expanding into new markets.

According to Canals (1994), the internationalization of a market must involve the acquisition of new customers, reduction in production costs, or optimization of production. Along with these goals, there is need for market penetration and for successfully taking one’s products to places in the world that result in dividends for the company and, thus, the country as well.

The development of economic processes in the enterprise, in view of the remaining factors of internationalization, include the variables of support and government incentives for competitiveness under a growing emphasis on the jurisdiction between states and the companies, through hierarchies and open opportunities for foreign direct investment (Buckley, 1998).

This leads to a reduction in prices and provides opportunities, including new options, distribution channels, and a wider range of customers, generating new businesses and products.

Accordingly, Johanson (1990) proposes five steps for internationalization: first is the already existing development of the company within the local market, followed by continuous exportation, the existence of potential partners, and the imminent establishment of commercial branches, and finally, the development of productive subsidiaries.

The concept is very complex, given the present situation of the companies in Latin American countries and the evident manner in which the large multinational companies focus on countries with large, fast-growing economies in which production is characterized by highly efficient economies. This is due to the necessity to not only consider the perspective of the organization alone (from a business management point of view) but also continue building up the discipline in accordance with its origin and evolution as well as based on the advances and perfection of other areas of knowledge, as is the case with information management based on Big Data (Rojas, Vega, Robayo, Montoya, & Piedrahita , 2016, pag. 2). Another study identifies three additional predominant characteristics of SMEs (attitude toward risk, market orientation, and networking propensity) which are important for businesses in the three detected dimensions of internationalization. (Dimitratos, Johnson, Plakoyiannaki, & Young, 2016)

The theory of internationalization focuses on national efficiency, opportunities for exportation, and massification in the global market, constantly improving one’s position and guaranteeing international competence for better price management.

Within the specific internationalization theory, it is extremely necessary to discuss the eclectic paradigm of Dunning (1988), which assumes patterns of internationalization and production; from its internal strategy to its manner of expansion, it is grounded in the specific conditions of the international market and in a preference for the product’s internationalization.

This theory is extremely important in that it contributes the necessary steps which are sufficient for a company to significantly grow overseas; it is very relevant in that it clearly indicates that it is not always profitable for a company to consider internationalization, depending on whether it is planned in a clear and specific manner.

For Dunning, the Know How, innovation, sustainability, or durability of a product are very important at the time it enters the global market; this involves reviewing the logistical distribution channels in each country, in addition to reviewing the efficiency level of production in the companies, machinery, equipment and infrastructure, access of products to border areas, and the use of multimodal transport (Kemp, 1984). Other important variables include idiosyncrasies, ideologies, and the focus of the state in relation to the company. According to Dunning, it is important for an efficient company to portray itself as a multinational with a high degree of market penetration. This model is also studied by Kojima (1985), who highlights the need for a company to generate competence and productivity from its system of scaled production.

In view of the challenges involved in internationalization, one must not ignore the contribution of Porter (1986) who considers competitiveness and market management from business administration to global penetration strategy. He presents an exportation strategy, a multinational strategy, globalization, and, finally, a decentralized exportation strategy.

Trujillo (2006) based his research on the Uppsala model, which was also analyzed by Johanson (1990), who proposed a relationship among the commitment of the market with an existing awareness of the environment, production strategy, and logistical distribution according to the conditions of each country. The same model was later analyzed by Buckley (1998) as well.

The challenge for a company lies not only in the sale of its products but also in its development through industrialization, the increase of its stock, and the qualification and skill of its labor force, as well as in the formulation of an operative plan that maximizes efficiency for the purpose of expanding both nationally and internationally as well as creating strategies for penetration and sustainability. This includes negotiation operations capable of resulting in profit, the manner in which Know How is put to use, and the opportunities provided by the state apparatus for the country’s industrialization (Johanson, 1990).

These authors also emphasize the need to change negotiation strategies when moving from a national to an international area of operation and the changes that take place in business scenarios due to intercultural factors and the existence of product competition. The discussion includes the question of whether the exportable supply is enough to generate profit for the company and add to the income of the country.

Hymer (1976) identifies the advantages that companies may possess or acquire, the industrial sectors, and the potential internal and external markets, including studies which verify the competitive advantages of Porter and Friedman, risks and cyclical variations of the market economy, deviations in supply and demand, and unclear economic policies regarding state governments toward the market. (Peñaloza, 2005).

This involves an expansive dynamic competition that may be referenced in the literature, in which Porter (2003) reviews the levels of competition of a territory according to the structure and rivalry existing among the companies. This depends on the conditions for the development of competition, the associations or opportunities to form partnerships, and finally, the conditions involving demand.

Concerning the progress of investment in these countries with the aim of improving their productive apparatus, Kojima (1982, pag. 152) states the following in his work : “Direct overseas investment must originate in the investing country in the sector (or activity) which has a comparative (or marginal) disadvantage and which may potentially be a sector which has a comparative advantage in the receptor country.” It is then possible to appreciate the advantages that international business affords as well as the difference which direct foreign investment makes in a company experiencing growth as compared to a company working alone. That is, the company that grows does so as a result of a judicious industrialization methodology, is characterized by innovation and sustainability in production, and operates through associations, conglomerates, and clusters that distinguish the exports of the company that wishes to trade internationally.

According to Trujillo (2006), models such as that of Canals are based on the supposed fruits of the expectation for globalization and, in addition, directly include external variables such as political risk and large economic fluctuations in some countries.

The decision of the company focuses more specifically on the economic reality of the country and on how the forces of the market influence the consumers’ changes and tastes, their standardization, and the publicity of the large brands which categorically affect their purchasing desires. It also deals with specific categories which direct the company to produce based on consumer preference and to penetrate markets based on consumer strategies.

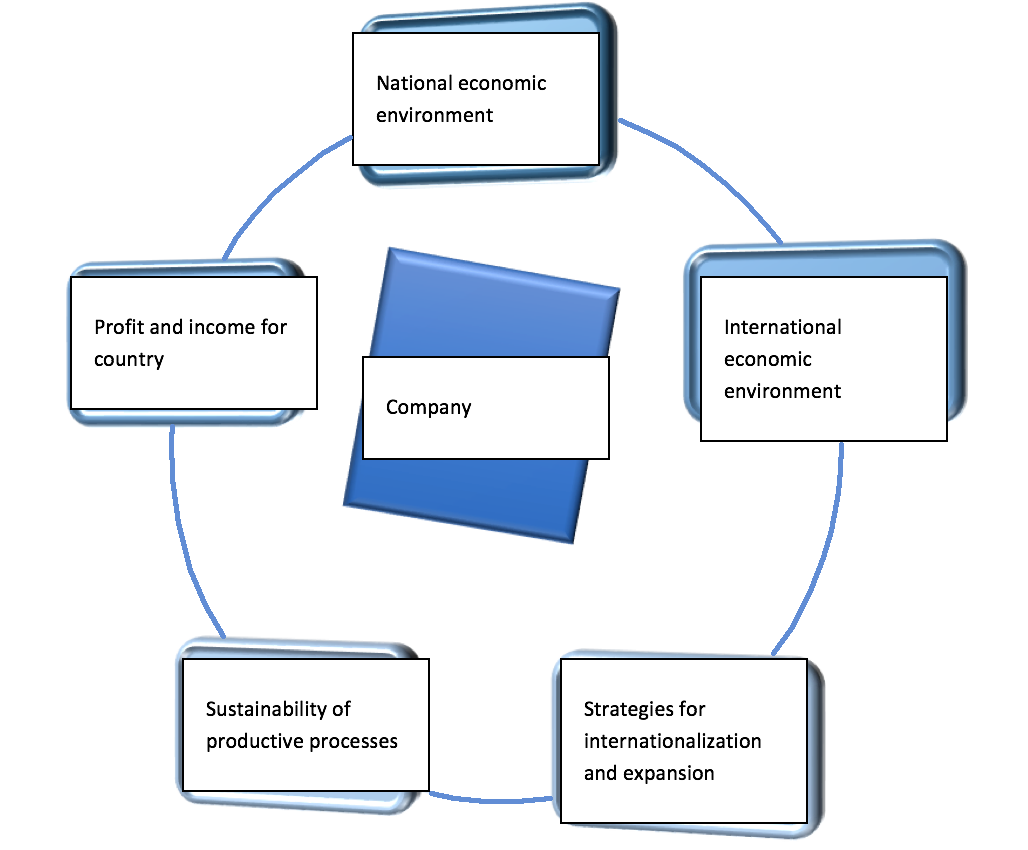

Chart 1

The company in relation to internationalization.

Source: The authors, 2013.

This type of company is very common in South American countries, and Colombia, the focus of this article, has a high concentration of companies involved in manufacturing and the development of products and services for their great exportation potential. Such companies have very similar characteristics, especially in countries having a great amount of industrial development, such as machinery, equipment, and automotive production. This involves the evolution of a company which directly supports the income of each of these countries.

It is important to note that these companies and these countries must adapt to these market situations. The countries must invest in technology and infrastructure and seek to form relationships with the markets where their goods and services are offered.

The ability of a company to adapt to the markets depends on economic efficiency and the possibility to adapt and, therefore, become a transnational company. The adaptation is more complex because it depends on the installed capacity and the structure of the country for development as well as market penetration. (Trujillo, 2006; Peñaloza, 2005)

It is equally important to explore the topic of clusters and the associations existing among companies for the purpose of internationalization, since according to the theories, the majority of companies having the most international options is large. Therefore, according to Porter (2003), the cluster becomes a relevant option for smaller companies. The definition of a cluster involves a geographical concentration of companies specialized in a specific business sector, which makes the exchange of specialized services possible.

The cluster is based on an organizing system that brings with it a concentration of competitive advantages, is organized according to networking theory, and is determined by a geographical sector.

The subject of location is widely discussed among business theorists such as Vernon (1990) and focuses on the development of company learning over time as well as on options and strategies of location. It is compared with and complemented by the Uppasala model, which is based on the examination of experience in order to determine whether to become international.

Some authors uphold that the Uppasala model has focused its attention on “knowledge of the foreign market” and has overestimated the importance of another type of knowledge, general knowledge regarding how to operate on an international scale, when this last consideration may explain how companies may skip steps in the process by using their accumulated experience and learning when to conduct business in foreign markets (Clark, 1997, pag. 123)”.

In addition to the location, the impact and strategy that the company has for its internationalization process is also important. One of these important considerations is the formation of clusters and relationships among companies for the purpose of internationalization, as in the cauterization system, in the company so that the study may bring us to the SMEs in Colombia.

“In the productive integration projects (local productive systems of small businesses), one may observe that the ability to innovate depends on the collaboration of numerous territorial agents that serve differing roles and possess differing levels of competence and knowledge concerning the productive process in the local use. The functioning of the productive process, as well as the transfer and acquisition of skills, therefore, has to do with all of these agents” (Pezzini, 2006, pag. 152).

Within business theory concerning internationalization, it is important to highlight the contributions of Porter (1986), who maintains that clusters are geographical concentrations of productive businesses, along with specialized suppliers, providers, and other institutions which are in some way linked to the activities in this sector, such as institutes, universities, and commercial associations, which although are always competing, nevertheless establish strong ties of cooperation due to having created economic networks which contribute to positive development in production (Garcia, 2006, pag. 13).

The topic of business agglomerations is summarized very well by Corrales (2007) in the following chart:

Chart 2

The topic of business agglomerations

Source: (Corrales, 2007)

The formation of clusters varies according to the region, idiosyncrasies, and strategies as well as the location of the company, according to Breault (2008 and Canals (1994). The formation of a cluster depends on several factors, the most important of which are qualified personnel, geographical location, resources and input, infrastructure, and the existence of academic research. It is possible to find other authors such as Canals (1994), Perego (2003), Mitnik (2011), and Martinez (2003) who agree with the importance of cluster formation in order to achieve better dynamics in the face of internationalization.

According to Porter (1986, pag. 35), “Regional clusters have the capacity to offer intangible profit such as knowledge, relationships, and motivation, on the local level and in a manner which cannot be equaled by distant rivals.” These groups or business agglomerations have similar and complementary characteristics for one product or service and possess the particular characteristic of focusing production on the same product for the purpose of economies of scale and wholesale.

It is important to emphasize the current significance of globalization and internationalization, especially in facilitating business competitiveness. Authors such as Porter, (1996), Corrales (2007) Galán, Galende, and González (2000), among others, affirm the need for companies to seek internationalization, including small companies, micro-enterprises, SMEs, and SMEs which are family-owned businesses having the opportunity for international expansion.

Marinez (2002) includes three definitions, namely that of industrial clusters (regional cluster), sector clusters, and value chains in production.

He emphasizes this by focusing on two areas. The first is based on similarity, and is, according to (Martinez, 2003, pag. 54), a “part of the assumption that economic activities are grouped into clusters as a result of their need to have similar conditions (regarding access to a qualified labor force, specialized providers, research institutions, etc.)”.

This issue is of great importance with regard to the need for a company to broaden its perspectives for production and competition, as well as its services and complementary goods, including the volume of the work generated.

The other focus is on the reciprocal need for generating interaction and innovation. The need to be located in the area in which the industry operates is also considered. This scenario is of even greater complexity because it supposes a greater degree of association and includes common innovative processes based on strategic partnerships, joint ventures, and business management based on competitiveness.

Similar issues are those of liquidity, the effect of national and international demand, and the opportunities for surplus including the cluster variable, in addition to strategies for internationalization in the face of competition, the market, the value chain, and the competitive demand (Porter, 1986).

In the case of the SME cluster, the demand must be a more determining factor than the supply for orientation of the product. It seeks to act with greater efficiency to the needs of communication, coordination, and mutual support. It is also confirmed that the degree of investment in technology is not great since “A gap is evident in terms of appropriation of technology with reference to small and medium companies in Colombia” (Rojas & Vega, 2011, pag. 192). This presents an opportunity for further exploration, since an advancement in this area may generate competitive advantages, especially when certain level of cooperation is achieved for the purpose of making progress in this area.

Association in a cluster, in addition to making progress in investment, can also resolve other difficulties relating to production, distribution, and marketing that would be impossible for a company to take on individually.

In order to do this, the company within the cluster must be willing to share information, since it must be geared toward demand and the needs of consumers in order to have the necessary capacity to increase market share. Those who cooperate within a cluster must consider the opportunity to improve the product quality and the importance of its reaching the consumer with added value; otherwise, such goals would be unattainable with the limited resources of each individual SME.

Businesses, especially those in Colombia, require new consolidation strategies in order to gain access to and sustain themselves in the international market. The national economies, which are constantly growing more interdependent, and the correlative production processes must deal with an exchange on the global level and a tendency toward a large-scale economy, involving low labor costs and competition in a capitalist market (Ianni, 1996).

It is therefore important to focus the study on the issue of small businesses and family-owned businesses, which,due to factors such as tradition, proximity, or necessity, have begun to manage their business within clusters.

In Colombia, according to law 590 from the year 2000 and law 905 from the year 2004, “a micro-enterprise is any economic unit managed by either a natural person or a legal person, which carries out activities related to business, farming, industry, commerce, or services, whether rural or urban, with a staff of up to 10 employees and assets totaling less than 501 minimum monthly wages as set by current legislation” (Ministry of Industry, Commerce, and Tourism, 2016).

Law 905 describes a business with a staff of 11 to 50 workers or total assets between 501 and 5000 minimum monthly wages as set by current legislation (Martinez, 2009).

Classification of the SME in Colombia

Type of Business |

Number of Employees |

Annual Assets ($) |

Micro-enterprise |

1–10 |

Less than 501 (MNMWG) |

Small enterprise |

11–50 |

501 to 5,000 (MNMWG) |

Medium enterprise |

51–200 |

5,001 to 30,000 (MNMWG) |

Source: (Martinez, 2009).

“A regional response to the diminished dynamism of the external demand is a greater regional integration which in turn permits the development of competitive advantages in non-traditional activities and sectors. In the absence of demand for exports, several countries in the region have been able to maintain dynamism by expanding their local markets. However, in many cases, the scale of the domestic market is limited or the companies may quickly encounter problems involving balance of payments for requesting the imports that such a process involves.” (CEPAL, 2013, pag. 12)

The proliferation of commercial treaties and the current business environment requires a greater amount of research and a better development of productivity and competitiveness.

Though it may be true that the majority of responses of the SMEs is defensive, possibly out of fear of cooperation, this attitude appears to be losing ground in Argentina (Gatto, 1985; Moori-Koenig , Quintar, & Yoguel, 1995). Other more concrete studies present numbers regarding cooperation in innovation for the purpose of seeking a greater degree of competitiveness, as is true of (Boscherini & Yoguel, 1995). It is important to review innovative activities while keeping in mind the degree of internationalization and cooperation among SMEs.

For this purpose, competitiveness is defined as the capacity of a company to organize itself in order to maintain systematic competitive advantages which improve its position in the market within the socioeconomic environment. Serna (2000, pag. 39) affirms with respect to competitiveness “that it is the capacity to produce or serve with the quality and excellence necessary in order to match the standard set by the remaining companies in the same area while seeking to offer the best, keeping in mind the various factors.” This results from a good association of labor.

The SMEs and the micro-enterprises in Colombia have been purely natural and spontaneous from their establishment, a characteristic which sets them apart from the rest of the word. They now have enormous responsibilities, including that of free trade agreements, bilateral agreements, trilateral agreements, multilateral agreements, and partial and complementary treaties. It is necessary to discuss the need to innovate and organize family businesses with support from government organizations such as FOMIPYME, CAF, and Proexport among others, which should be responsible for promoting this change and should give a strong impetus to strategic organization. This should be done bearing in mind the comparative and competitive advantages of these businesses by establishing logistical distribution channels which are defined and guided by the building up of multimodal value. The goal of such innovation is to maximize Colombia’s system of sub-regional exchange and open regionalism in view of the current world environment. Despite studies that gives the individual a perception of normative and regulatory aspects of the institutions, the interaction between both, as well as the interaction between the normative and the cognitive aspects of the institutions explain the decision to take on international operations (Garcia-Cabrera, Garcia-Soto, & Duran-Herrera, 2016). This issue must be reviewed carefully as an essential aspect of change.

It is necessary to reclaim the production processes and qualified labor in homogeneous conditions of support and cooperation to implement strategies such as joint venture and strategic partnerships that could be a means of generation and placing new products in both national and international markets.

For this reason, special attention must be given to the creation of clusters, as well as their consolidation, promoting a greater degree of business partnership among SMEs, with the aim to position these companies as important and meaningful in the generation of regional GDP. This includes strategies of globalization and characterization of products with added value, which distinguish themselves before the international market, which is highly competitive and productive.

SMEs must concentrate their efforts in order to obtain correct information in an efficient manner with regard to information management by preparing intelligence maps. The analysis concluded that there is heavy dependence on the production chains of large businesses but that these sectors must also seek to establish information channels in order to make decisions based on business intelligence.

It is essential that the SMEs be located near Latin American universities, where they may have access to information generated by applied investigation carried out in their research centers, thus providing incentives for their developing relationships with the academic sector early on. Within the cluster environment, the opportunities for partnership and the benefits of cooperation must be taken advantage of in order to identify strategic common goals and strengthen the ability to negotiate.

Bilkey, W., & Tesar, G. (1977). The Export Behavior of Smaller-sized Wisconsin Manufacturing Firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 8, 93 - 98.

Boscherini, F., & Yoguel, G. (1995). Innovative processes in SMEs: some consideration about the Argentine case. Buenos Aires: CEPAL-IDCJ.

Breault, R. (2008). The evolution of structured clusters. EEUU.

Buckley, P. J. (1998). Analyzing foreign market entry strategies: Extending the internalization approach. Journal of international business studies, 539-561.

Calof, J., & Beamish, P. (1995). Adapting to Foreign Markets: Explaining Internationalization. International Business Review, Vol.4, No.2, 115-131.

Canals, J. (1994). La internacionalización de la empresa: cómo evaluar la penetración en mercados exteriores. España: Mac Graw Hill.

Canals, J. (1994). La internacionalización de la empresa: cómo evaluar la penetración en mercados exteriores. Madrid: McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España.

Castels, M. (1999). Glabalización, identidad, estado. PNUD, 3-26.

Cavusgil, S. (1980). On the Internationalization Process of Firms. European Research, 8, November, 272-281.

CEPAL, O. (2013). Perspectivas económicas en América Latina. Chile: CEPAL.

Charles, H. (1994). International Business and Economics. NY: McGraw-Hill School Education Group.

Clark, T. P. (1997). The process of internationalization in the operating firm. International Business Review, 605-623.

Corrales, S. (2007). Importancia del cluster en el desarrollo regional actual. Frontera norte, 173-201.

Dimitratos, P., Johnson, J., Plakoyiannaki, E., & Young, S. (2016). SME internationalization: How does the opportunity-based international entrepreneurial culture matter? International Business Review, 1211-1222.

DNP. (2007). Agenda para la productividad y Competitividad. Departamento nacional de Planeación, 4-47.

Dunning, J. H. (1988). Explaining international production. London: Unwin Hyman, 80.

Galan, J., Galende, J., & Gonsalez, J. (2000). Factores determinantes del proceso de internacionalización. El caso de Castilla y León comparado con la evidencia española. Economía Industrial. Nº 333, 33 - 48.

Galvis, J. (1998). Los Procesos de Internacionalización de la Empresa: Causas y Estrategias que lo Promueven. Applied Economics, 621-629.

Garcia, J. (2006). Ventaja competitiva a través del desarrollo de clusters empresariales. Departamento Académico de Ciencias Administrativas- redalyc, 30-34.

García-Cabrera, A., García-Soto, M., & Durán-Herrera, J. (2016). Opportunity motivation and SME internationalisation in emerging countries: Evidence from entrepreneurs’ perception of institutions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal Volume 12, Issue 3, 879 - 910.

Gatto, F. (1985). Las exportaciones industriales de pequeñas y medianas empresas. Buenos Aires: Universidad de Quilmes.

Hymer, S. (1976). The international operations of national firms: A study of direct foreign investment. Cambridge, MA: MIT press, 139-155.

Ianni, O. (1996). Teorías de la globalización. Siglo XXI.

Johanson, J. &. (1990). The mechanism of internationalisation . International marketing review, 4.

Kemp, M. C. (1984). A note of the theory of international transfers. Economics Letters, 259-262.

Kitchenham, B. (2004). Procedures for performing systematic reviews . Keele, UK, Keele University, 33(TR/SE-0401), 28. doi:http://doi.org/10.1.1.122.3308

Kojima, K. (1982). Macroeconomic versus international business approach to foreign direct investment. Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics, 23, 630–40.

Kojima, K. (1985). Japanese and American direct investment in Asia: a comparative analysis. Hitotsubashi Journal of Economics, 1-35.

Kotler, P. (2005). Los diez pecados capitales del Marketing, . Barcelona: Gestión.

Lazzeretti, L. (2006). Distritos industriales, clusters y otros: un análisis "trespassing‟ entre la economía industrial y la gestión estratégica. Revista Economía Industrial, nº 359, 59-72.

López, A., Méndez, D., Paz, A., & Arboleda, H. (2016). Desarrollo e Instrumentación de un Proceso de Vigilancia Tecnológica basado en Protocolos de Revisión Sistemática de la Literatura. Development and Implementation of a Technology Surveillance Process Based on Systematic Literature Review Protocols., 27(4), 155–164. doi:http://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-07642016000400017

Marinez, A. N. (2002). Identificación de cluster y fomento a la cooperación empresarial caso baja california. Momento Económico, 39-57.

Martínez, A. N. (2003). Identificación de cluster. fomento a la cooperación internacional. El csao baja California. Momento Económico, 39-57.

Martinez, P. (2009). PYME estrategia para su internacionalización. Barranquilla: Ediciones Uninorte.

Melin, L. (1992). Internationalization as a Strategy Process. Strategic Management Journal, 13, 99–118.

Ministerio de Industria Comercio y Turismo. (15 de 2 de 2016). Definición Tamaño Empresarial Micro, Pequeña, Mediana o Grande. Obtenido de http://www.miPYMEs.gov.co/publicaciones/2761/definicion_tamano_empresarial_micro_pequena_mediana_o_grande

Mitnik, F. (2011). Políticas y programas de desarrollo de cadenas productivas,. Cordoba: Editorial Copiar BID.

Moori-Koenig , V., Quintar, A., & Yoguel, G. (1995). Estrategias, gestión empresarial y posicionamiento competitivo en las PYMEs, CEPAL. Buenos Aires: Mimeo.

O, I. (2006). Teorias de la Globalización. Mexico: Siglo XXI.

Olivares Mesa, A. (2005). La globalización y la internacionalización de la empresa:¿ es necesario un nuevo paradigma? Estudios Gerenciales, 21(96), 127-137.

Peñaloza, M. S. (2005). Competitividad:¿ nuevo paradigma económico? Universidad de Puerto Rico• Recinto de Rio Piedras, 10-43.

Perego, L. (2003). Competitividad a partir de los agrupamientos industriales: un modelo integrado y replicable de clusters productivos. Eumed. net, 16-82.

Petersen, K., Feldt, R., Mujtaba, S., & Mattsson , M. (2008). Systematic Mapping Studies in Software Engineering. 12Th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, 17, 10., 12 - 53. doi:http://doi.org/10.1142/S0218194007003112

Pezzini, M. (2006). Sistemas productivos locales de pequeñas empresas como estrategias para el desarrollo local. Los casos de Dinamarca, Emilia Romagna y Comunidad Valenciana. Revista Economía Industrial, nº 359, 185-200.

Porter, M. (1986). Competition in global industries. Londres: Harvard Business Press.

Porter, M. (1996). Competitive advantage, agglomeration economies, and regional policy. International regional science review, 19(1-2), 85-90.

Porter, M. (2003). Location, Cluster, and Company Strategy. 43 - 64.

Porter, M. C. (1996). ompetitive advantage, agglomeration economies, and regional policy. International regional science review 19(1-2), 85-90.

Reid, S. (1982). The Impact of Size on Export Behaviour in Small Firms. New York: Praeger Ed.

Rojas , S., Vega , R., Robayo , O., Montoya, L., & Piedrahita , G. (2016). Big data: Trend emerging from research in marketing. Espacios Vol. 37 (Nº 38), 2 - 5.

Rojas, S., & Vega, R. (2011). Nivel de apropiación del Internet y nuevas tecnologías en las PYMEs colombianas exportadoras o potencialmente exportadoras. Revista Punto de Vista, 183 -194.

Serna, H. (2000). Mercadeo Interno. Bogotá: 3r Editores.

Trujillo, M. R. (2006). Perspectivas teóricas sobre internacionalización de empresas. Administración. Borradores de Investigación, 1-72.

Turnbull, P. (1987). challenge to the stages theory of the internationalization process. Managing export entry and expansion, 21-40.

Vázquez, A. (2009). Desarrollo local, una estrategia para tiempos de crisis. Universitas Forum, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1 - 11.

Vernon, R. (1990). ¿ Pueden los Estados Unidos negociar para la igualdad de trato comercial? Harvard Deusto business review, (41), 68-74.

Williamson, O. (1996). Economic organization: The case for candor. . EEUU: Academy of Management Review.

Wind, Y., Douglas, P., & Perlmutter. , V. (1987). Guidelines for Developing International Marketing Strategies. Journal of Marketing (April), 14-23.

1. Greater Colombian Polytechnic University Institute. Economist, specialist in Integration into the International System, Master’s in Education, university professor with more than 14 years of experience, having published several articles in both national and international indexed journals. She is currently a tenured professor in the international department of the Greater Colombian Polytechnic University Institute. Email: amoraram@poli.edu.co

2. Greater Colombian Polytechnic University Institute. Social Communicator, Journalist, Specialist in Corporate Communications, Master’s in Strategic Marketing Management, and Editor at the Greater Colombian Polytechnic University Institute. Email: ednorman@poligran.edu.co