Vol. 38 (Nº 51) Year 2017. Page 31

Rumiana LILOVA 1; Aneliya RADULOVA 2; Alexandrina ALEXANDROVA 3

Received: 05/10/2017 • Approved: 18/10/2017

2. Institutional Description of the European Fiscal Pact

3. Discussion on "Optimal" Government Debt Levels

ABSTRACT: This article examines the relation between fiscal policy and government indebtedness in EU Member States whose average debt levels were higher than the EU-27 average through the 2002-2016 period. The main body of the article focuses on the theoretical concepts about the relationship between fiscal policy and government debt; it assesses the impact, which the debt financing policy has on the economic system and analyses development stage and trends of the main fiscal policy and debt burden instruments in a group of EU Member States differentiated for the survey. |

RESUMEN: Este artículo examina la relación entre la política fiscal y el endeudamiento del gobierno en los Estados miembros de la UE cuyos niveles de deuda promedio fueron más altos que la media de la EU-27 durante el período 2002-2016. El cuerpo principal del artículo se centra en los conceptos teóricos sobre la relación entre la política fiscal y la deuda pública; evalúa el impacto que la política de financiación de la deuda tiene en el sistema económico y analiza la etapa de desarrollo y las tendencias de los principales instrumentos de política fiscal y carga de la deuda en un grupo de Estados miembros de la UE diferenciados para la encuesta. |

Over the last decades, one of the major problems faced by modern economies has been that of deficit financing. The opportunities for limiting the deficit, and hence, the growth of debt, have been the priority of any economic community. The European Union, as an economic community of many countries with a common market and a common currency, has adopted a number of legislative changes and measures designed to curb the growth of deficit in the member-states and prevent the negative consequences of the growing debt crisis. The economic governance of the EU is implemented in three directions: monitoring, prevention and correction. The main objective of the EU economic governance framework is ‘to identify, prevent and correct problematic economic trends such as excessively high levels of government deficit or government debt which may hinder growth and expose economies to a risk’ (European Commission, 2017).

The relatively prominent level of government indebtedness of the EU Member States, which are registered after 2008 as a result of the global economic crisis, raises questions on the ways of financing the public spending, the “inevitability” of the debt indebtedness, the “optimal” debt levels and its management. Theoretical queries, empirical analyses, and normative documents regulating the fiscal responsibilities of the EU member states aim to identify the problems and their solutions in order to establish equilibrium in the financial systems of the countries in the community (Kotova, 2013, 2014).

The main objective of this study is to examine and determine the parameters and the extent of interconnectivity between the levels of government debt and basic economic factors such as deficit, budget revenues, budget expenditures and economic growth (measured by GDP growth). Furthermore, this research paper will try to assess the impact of Europe’s fiscal pact on the fiscal sustainability of the Community. The level of government indebtedness in a particular group of the EU Member states is considered as an object of the study and the impact fiscal instruments and rules have on government debt levels is considered as a subject. Comparative and regression analysis are the methods which were used in the study.

The body is built as it follows: Section 2 includes a brief institutional description of the European Fiscal Pact, which is based on the discussion of the included in it theoretical and normative statements on the “optimal” levels of government debt; Section 3 comments on various policies restricting the government debt level which serve as theoretical illustrations; Section 4 provides the study with the analysis of the level of influence exerted by the key factors on the government debt levels. The analysis is based on a panel regression model which takes account of the effect of the model variables on the government debt of each European member state included in the research for every year of the observed period. The conclusion summarizes the findings of both the comparative and the regression analyses and their relationship with the theoretical formulations.

As one of the largest supranational integrational and economic structures, the European Union’s main priority is to create conditions for the free movement of capital, goods and labour within the boundaries of the Community.

In order to create this environment and to ensure growth-friendly conditions for the single market development, it is necessary for the members of the Union to conduct common economic, tax and fiscal policies. According to Mario Draghi (2012), the European Union is “an economic union that fosters sustained growth and employment; and a fiscal union with enforceable rules to restore fiscal capacity”. These statements led our team of researchers to the formulation of three key points for defining the European Union’s fiscal system: fiscal capacity, fiscal responsibility and fiscal rules.

Referred to as a concrete, accurate and based on an in-depth study definition on fiscal capacity is the one of Jorge Martinez-Vazquez and L. F. Jameson Boex (1997), according to which it is “a measure of a government’s ability to raise revenues for provision of services, relative to the costs of service responsibilities”. According to these researchers, fiscal capacity might also be defined as “the potential ability of the government to finance a standardized basket of public goods and services by raising revenues from its own source”. The optimization of the fiscal capacities of the Member States separately and of the European Union as a whole requires undertaking fiscal responsibility which should be in compliance with the generally applicable and fundamental for the European fiscal policy budgetary procedures, fiscal rules and regulations.

When conducting a responsive policy that is adequate to the economic situation in the European Union, it is specifically important to introduce a mechanism, consisting of regulatory acts, fiscal instruments, rules and recommendations which are able “to maintain fiscal discipline, foster economic and macroeconomic growth, and ensure the stability of public finance”(Dziemianowicz, & Kargol-Wasiluk, 2015).

On the one hand, the introduction, adjustment, adaptation and improvement of such a mechanism to the changing economic environment is a contemporary issue that dates back to signing the Treaty of Rome in 1957 and the foundation of the European Union. On the other hand, facts such as the differences in the stage of economic development and integration of the countries of the Union, the non-identical country-led fiscal policies and the contrasts between the countries’ budget imbalances are at odds with the principle of a common European fiscal policy.

This contradiction requires faster development and implementation of common fiscal adjustment rules focused on budget imbalances and deficit financing problems in the Community. The first measures related to the regulation of budget imbalances and deficit financing were introduced by the European Commission in 1989 with the review of the Delors’ 1 Plan. The plan provided for the establishment of the Economic Monetary Union between the EU Member States which, according to S. Blavoukos and G. Pagoulatos (2008), “entailed significant process of fiscal adjustment to meet the Maastricht eligibility criteria”.

The establishment of the Economic Union consisted of three stages, the second and the third of which were closely related to the Maastricht Treaty (Treaty on the European Union, 1992) and especially to the convergence criteria that need to be met by the countries. The focus was on the implementation of a common policy for curbing the rate of inflation; the fiscal policy of the community members; their currencies and interest rates. In response to the sovereign debt crisis (Mastern, & Gnip, 2016), the Maastricht treaty “creates the first such international budgetary treaty, with each country converging toward the same target” (Savage, 2001). Article 104c of the Maastricht Treaty provides that “all Member States shall avoid excessive government deficit and keep its value below 3% of the GDP of the country, while the ratio between the government debt and the GDP shall not exceed 60%”. Once adopted, the criteria became the cornerstone of the budgetary policies of all the countries in the Union.

The dynamically changing in the 1990s European economic environment along with the European Union’s expansion naturally led to the necessity for updating the existing fiscal rules and taking the next significant step towards overcoming the debt and budget deficits problems of the Member States. In order to meet this necessity, the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) was signed in Amsterdam in 1997. The Pact is a set of rules designed to ensure that the EU Member States will succeed to maintain their solid levels of public finance and will coordinate their fiscal policies. The main objectives of the Pact focus on two major aspects: to prevent fiscal policies from targeting at potentially problematic areas and to correct excessive budget deficits and excessive public debt. Several regulations of the European Commission focus on deficit financing. As a result of the ongoing global economic crisis and its negative effects on the economies of some of the EU Member States, the European Commission has consistently adopted amendments. In 2011 and 2013 Excessive deficit rules and procedures known as the ‘Six-Pack’ and the ‘Two-Pack’ were adopted and in 2016 the ‘Code of Conduct’, which contains specifications on the SGP implementation and provides guidelines on the format and content of Stability and Convergence Programs, was introduced.

A considerable number of European Commission regulations aims at taking actions to strengthen the supervision and monitoring over the budgetary situation and the excessive deficit-financing problem of the Member States. The surveillance and coordination of their economic policies helps identify excessive deficits, facilitates and clarifies the excessive deficit procedure and limits the occurrence of excessive budget deficits. Tracking its dynamics and researching for possibilities for its determination is among the main EU fiscal policy objectives. It directly affects not only the budgetary, taxation and financial systems, but also the reverse dependency between GDP and the deficits of the Member states. Hence, it also affects economic growth.

Despite the different approaches and analytical models that researchers apply, they consolidate their conclusions into the thesis that determining the optimal debt level is in a direct dependency of the economic development level of countries. That is why they differentiate three main groups of countries: developed, developing and poor. The prevailing opinion on the matter (Buiter, 2003; Caner et al., 2010; Balazs, 2015) is that the optimal debt levels in the developed countries amount to 60%. The same is claimed by the IMF in its report “Fiscal Monitor: Balancing Fiscal Policy Risks” of 2012. At the same time, C. Checherita and Ph. Rother’ s (2010) and S. Ceccheti, M. S. Mohanty and Z. Fabrizio’s works (2011) state that the optimal debt level in the developed countries is 85% -90%. In regard with the developing countries, it is argued that the optimal debt level is achieved within 30% -40%: according to C. Patillo, H. Poirson and L. Ricci (2002) at a level of 35-40%; according to Balazs E. (2015) at 30% and according to the IMF’s “Fiscal Monitor: Balancing Fiscal Policy Risks” report at the level of 40%. Significantly fewer researches have been conducted for determining the optimal debt level in poor countries. B. Clements, R. Bhattacharya, and T.Q. Nguyen (2003) claim that the optimal debt level in developing countries is less than or equal to 50%.

There is a complex cause-and-effect relationship between fiscal policy and economic growth, operating in both directions. For example, the existence of imbalances in the fiscal balance may be a result of either a discretionary fiscal policy (e.g., a change in tax rates or government expenditure) or because of changes in the economic activity. The dilemma here is whether and when to apply the specific instruments of discretionary fiscal policy or to entirely rely on the operation of the cyclical automatic stabilizers because of their ability to ensure sustainable economic growth. This is a question whose answer still could not be found in the economic literature because a commonly accepted conceptual definition has not been established – the ideas and views of economists move from one extreme to another. An area of agreement in the established and put into practice economic theories and views regarding the ways in which instruments and approaches of different countries maintain their public finances in equilibrium is that they “arise” as a consequence of socio-economic conditions in a certain historical moment.

The 1930s Great Depression gave birth to Keynes’s idea for aggregate demand stimulating by increasing government procurement as anti-cyclical regulators for the economic stabilisation in various economic cycles (Keynes, 1936).

Despite the very disputed character of the disadvantages of the effects of the applied ideas for the impact of fiscal policy on the level of domestic aggregate demand, there is a large body of literature on the inadequacy of the discretionary fiscal policy mechanism as long as they do not lead to fiscal stability in the long run (Balassone, & Franco, 2000). Changes in the world’s economic development in the 1950s raise doubts over the appropriateness of the ideas of debt financing imposed by Keynes.

For this reason, monetarism supporters base their views on the following general statements: firstly, the more the consumer spending is less sensitive to the current level of aggregate supply, the more limited is the fiscal multiplier role in the economy (Friedman, 1957); secondly, the interest rates rise as a consequence of a government debt increase causes private investment ‘crowding-out’, which may cause adverse effects on economic growth in a long term (Spencer, & Yohe, 1970); thirdly, private sector spending is relatively more productive than the government one due to the inertia of the administration employees (Krueger, 1974); fourthly, government intervention in the economy weakens the adaptive capacity of the economy to crisis situations (Friedman, & Schwartz, 1963), and the implementation of a fiscal policy “not according to the rules, but under the circumstances” leads to the “distortion” of the economic subjects’ expectations (Friedman, 1960).

The connotation of the discussion on approaches to defining the parameters of fiscal policy that aim at overcoming the consequences of cyclical economic crises and affect the sustainability of public finances is how far they can and should be unified. The attempts to pursue a coherent fiscal policy within the Union and the declared striving for “balancing” of the fiscal rules across the Member States are justified inasmuch as the fiscal policy aimed at stimulating savings or limiting and promoting their consumption over a long period of time, is perceived by economic actors as sustainable and predictable. On this basis, it can be said that its instruments should be used to overcome the shortage or surplus of savings in the economy. The formation of budget surpluses in times of upsurge and economic growth as a consequence of the seizure of income by businesses through higher tax rates is a form of regulation of aggregate savings in the economy. Under these conditions, fiscal measures would have a remarkable positive effect compared to the monetary ones. Fiscal policy instruments – taxes and government spending – can impact economic processes in the short and long run. Disposable income and aggregate demand are affected in the short run. However, the regulation of aggregate supply, related to the stimulation of labour activity, savings and investments, appears when a longer period of time is observed.

The existing issues and contradictions, regarding the effectiveness of the “fiscal compact” measures implied by the EU in 2012, aim to keep the deficit levels and the relative levels of government debt and hence to avoid future financial crises. On the one hand, the adoption of rigorous fiscal consolidation rules can have a negative impact on production and economic growth; on the other hand, excessively high levels of sovereign debt lead to serious financial crises. Doubts about the appropriateness of imposing tighter fiscal rules in the Union are expressed by Bird and Mandilaras (2013), according to whom the limitation of “discretionary fiscal policy by imposing constraints on the size of structural deficits may be a case, as recently articulated by Blanchard et al. (2010), for increasing the degree of automatic fiscal stabilization, such that stronger counter-cyclical effects are built into the fiscal balance”. The impossibility of determining the “optimal” level of debt by virtue “can never be established some mechanical rule or threshold” (Ostry et al., 2015). Overcoming this “hurdle” requires the determination of the “safe” debt level in each Member State through the conduction of special stress tests which take “... the interaction of public finances and the economy into account" (Easterly, & Rebelo, 1993).

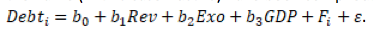

The aim of the survey is to establish the degree of dependence between the levels of government debt and the values of revenues, expenditures and GDP in the EU Member States for the period 2002-2016 by implementing a based-on panel data regression model. The model allows obtaining information on the debt levels changes over time and the possibility of assessing the differences between the examined countries on the assumption that there is a correlation between the indicators of a particular country over a period of time and an absence of such a correlation when examining the countries separately.

The model parameters are as follows: n - 28 EU Member States; t - 14-year period; variables: debt: Government consolidated gross debt (as % of GDP) - dependent variable , where i = 1 .... 28, t - index of the period; rev: Total general government revenue (in EUR million); exp: Total general government expenditure (in EUR million); GDP: Gross domestic product at market prices (in EUR million).

In this part, it should be noted that the model does not claim to be exhaustive in its selection of variables affecting the level of government debt. Factors such as structure of revenues and expenditures, structure of debt and interest rates, applied social policy in the country concerned, etc. remain outside the functional dependence. However, the single purpose of the regression analysis is to assess the impact of the main factors on the debt levels, considering the influence of the applied fiscal instruments which are directly related to the economic growth, measured by GDP growth.

The evaluation of the outlier panel data with a pooled OLS estimator, a “between” estimator, a fixed effects estimator (within), a first-difference estimator and a random effects estimator allowed for the selection of the most appropriate model between a fixed-effect model (FE model) and a model with random effects (RE model). The reasoning behind our choice is determined by testing the Lagrange multiplier models and the Hausman test (see Table 1).

Table 1. Results of the conducted test for estimation of the project importance

Plmtest (pooling), Lagrange Multiplier Test – (Honda) for balanced panels data: Y ~ X normal = 40.095, p-value < 0.00000000000000022 alternative hypothesis: significant effects |

As much as p-value е <0.05, the model is applicable |

Phtest (random, fixed), Hausman Test data: Y ~ X chisq = 7.807, df = 3, p-value = 0.05017 alternative hypothesis: one model is inconsistent |

As much as p-value е <0.05, the fixed effects model is applicable |

Source: Authors

Considering the fact that the test results show that both models are statistically significant (p <0.05), the criterion for selecting the fixed effect model, in this case, is the calculated highest value of R-Square = 0.164 in the Hausman Test (the occasional effects model registered R-Square = 0.14793).

The panel model with individual fixed effects aims to assess the individual (fixed) effect of the impact of the government debt variables on each EU member state separately and for each year of the analysed period. For this purpose, instrumental variables (dummies), equal to the number of states minus 1 (i.e., 27 dummies), sorted according to the first letter of the name (in this case Austria) have been compiled.

The results from the model, shown in Table 1 can be interpreted as follows:

Firstly, the interrelationship between the analysed factors is significant (R-squared: 0.8927);

Secondly, the amount of government revenue does not affect the level of government debt (Revenue: -0.00004242);

Thirdly, in most of the member countries of the community, the examined factors influence the level of government debt. For the countries, where the model variables are not a significant factor, it can be assumed that the specific for the country factors had greater influence on the debt.

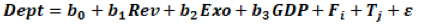

As it has been shown, one of the objectives of this study is to determine the presence and the extent of the influence of the limiting conditions embraced with the pact in terms of debt and deficit levels. For this purpose, a model with time-determined fixed effects is tested, in the final equation of which an additional factor , representing the number of years has been introduced (Table 2).

The equation in the model is:

Table 2. Panel model with individual fixed effects

treg2 <- lm(Debt ~ Country+Revenue+Expenditure+GDP) summary (treg2) Call: lm(formula = Debt ~ Country + Revenue + Expenditure + GDP) Residuals: Min 1Q Median 3Q Max -38.967 -7.735 -0.851 6.900 54.723 |

||||

(Intercept) |

58.86426210 |

4.67087625 |

12.602 |

< 0.0000000000000002 *** |

Belgium |

20.14858186 |

5.58250038 |

3,609 |

0.000347 *** |

Bulgaria |

-35.03498752 |

5.99271470 |

-5.846 |

0.000000010654512 *** |

Croatia |

-3.75286285 |

5.96025638 |

-6,3 |

0.529295 |

Cyprus |

5 |

6.04180302 |

2.143 |

0.032719 * |

Czech Republic |

-29.26522552 |

5.77237537 |

-5.070 |

0.000000617032561 *** |

Denmark |

-32.85361172 |

5.63939625 |

-5.826 |

0.000000011931845 *** |

Estonia |

-52.32396622 |

6.05042614 |

-8.648 |

< 0.0000000000000002 *** |

Finland |

-22.69559033 |

5.65798276 |

-4.011 |

0.000072437630524 *** |

France |

-108.96130923 |

16.13681551 |

-6.752 |

0.000000000053107 *** |

Germany |

-94.71106485 |

22.69623637 |

-4.173 |

0.000037115162969 *** |

Greece |

66.43914822 |

5.67441794 |

11.709 |

< 0.0000000000000002 *** |

Hungary |

6.19089029 |

5.80274794 |

1.067 |

0.286683 |

Ireland |

0.55747118 |

5.96258375 |

0,093 |

0.925559 |

Italy |

-24.70560788 |

13.10087591 |

-1.886 |

0.060067 |

Latvia |

-31.66338351 |

6.03684441 |

-5.245 |

0.000000257190375 *** |

Lithuania |

-30.80516524 |

6.00936945 |

-5.126 |

0.000000466929108 *** |

Luxembourg |

-45.25881754 |

5.97658239 |

-7,573 |

0.000000000000269 *** |

Malta |

6.91355227 |

6.07744875 |

1.138 |

0.255998 |

Netherlands |

-27.32558462 |

6.70093306 |

-4.078 |

0.000055140943890 *** |

Poland |

-22.02185949 |

5.97468661 |

-3.686 |

0.000260 *** |

Portugal |

25.63858504 |

5.70032506 |

4.498 |

0.000009079184615 *** |

Romania |

-34.90262185 |

5.88526853 |

-5.931 |

0.000000006673297 *** |

Slovakia |

-18.40773252 |

5.92183735 |

-3.108 |

0.002019 ** |

Slovenia |

-16.09906233 |

5.98282627 |

-2,961 |

0.007434 ** |

Spain |

-30.40959717 |

11.37963941 |

-2.672 |

0.007851 ** |

Sweden |

-36.50038303 |

5.62868179 |

-6.485 |

0.000000000270150 *** |

United Kingdom |

-72.53340620 |

22.63755306 |

-3,204 |

0.001466 ** |

Revenue |

-0.00004242 |

0.00007744 |

-0,548 |

0.584191 |

Expenditure |

0.00028504 |

0.00004415 |

6.455 |

0.000000000321736 *** |

GDP |

-0.00006940 |

0.00003429 |

-2,024 |

0.043650 * |

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 |

||||

Source: Authors

The results of the model, which demonstrate a high statistical significance with a correlation coefficient equal to 0.8927 also show that time-specific fixed effects occur after 2009 (see Table 3).

Table 3. Panel model with individual time-based fixed effects

Years Dum <- as.factor (Years)> preg3 <- lm(Debt ~ Country+YearsDum+Revenue+Expenditure+GDP)> summary(preg3) Call: lm(formula = Debt ~ Country + Years Dum + Revenue + Expenditure + GDP) Residuals: Min 1Q Median 3Q Max -27.533 -6.456 -0.601 5.143 43.945 |

||||

|

Estimate |

Std. Error |

t value |

Pr(>|t|) |

(Intercept) |

66.86883795 |

3.98490175 |

16.781 |

< 0.0000000000000002 *** |

Belgium |

24.45325397 |

4.23610108 |

5.773 |

0.00000001638103689 *** |

Cyprus |

-4.03592708 |

4.73774876 |

-0.852 |

0.394832 |

France |

1.73148277 |

14.57547453 |

0.119 |

0.905502 |

Germany |

24.54474795 |

19.70770797 |

1.245 |

0.213748 |

Greece |

60.76248579 |

4.31402482 |

14.085 |

< 0.0000000000000002 *** |

Hungary |

-5.94711624 |

4.47797849 |

-1.328 |

0.184959 |

Ireland |

-9.19478523 |

4.55490659 |

-2.019 |

0.044234 * |

Italy |

47.99331196 |

11.41925071 |

4.203 |

0.00003298473259409 *** |

Malta |

-10.54849647 |

4.77499481 |

-2.209 |

0.027771 * |

Poland |

-23.16930761 |

4.53235679 |

-5.112 |

0.00000050923493868 *** |

Portugal |

17.33677245 |

4.35110649 |

3.984 |

0.00008127742376916 *** |

Spain |

1.49881876 |

9.16001849 |

0.164 |

0.870114 |

United Kingdom |

12.63382354 |

18.80275160 |

0.672 |

0.502052 |

2003 |

-0.11094639 |

3.07696239 |

-0.036 |

0.971256 |

2004 |

0.00835166 |

3.08344470 |

0.003 |

0.997840 |

2005 |

-0.48337745 |

3.09336522 |

-0.156 |

0.875910 |

2006 |

-1.71667277 |

3.11555306 |

-0.551 |

0.581961 |

2007 |

-2.86655997 |

3.15402707 |

-0.909 |

0.364009 |

2008 |

-0.84153370 |

3.16659971 |

-0.266 |

0.790575 |

2009 |

5.22250463 |

3.22904969 |

1.617 |

0.106643 |

2010 |

11.20809099 |

3.26551423 |

3.432 |

0.000665 *** |

2011 |

16.64806638 |

3.22461397 |

5.163 |

0.00000039557154795 *** |

2012 |

20.20157316 |

3.24089954 |

6.233 |

0.00000000122973524 *** |

2013 |

24.07004127 |

3.23360560 |

7.444 |

0.00000000000067677 *** |

2014 |

25.68436465 |

3.25903778 |

7.881 |

0.00000000000003563 *** |

2015 |

24.83108961 |

3.31063754 |

7.500 |

0.00000000000046514 *** |

2016 |

24.76414745 |

3.30834615 |

7.485 |

0.00000000000051391 *** |

Revenue |

-0.00003648 |

0.00006109 |

-0.597 |

0.550769 |

Expenditure |

0.00014703 |

0.00003749 |

3.922 |

0.000105 *** |

GDP |

-0.00006244 |

0.00002640 |

-2.366 |

0.018510 * |

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 |

||||

Source: Authors

This fact leads to the following reflections:

The last two conclusions do not allow us to firmly state whether and to what extent the examined factors and the applied fiscal policy affect the debt levels. However, they should be considered as a subject of further research.

This study focuses on several key issues related to the necessity of a greater fiscal responsibility from the EU member states’ side in order to establish stability and economic growth in the community.

As far as the requirements of the Pact focus on two main indicators (government debt and budget deficit) for measurement of the fiscal stability in the countries of the Community, it is important to state that the study scope was limited to the conduction of a comparative and regressive analysis of the interdependence between the main economic indicators and their impact on the economic growth. The analysis of the theoretical concepts on the relationship between fiscal policy and government indebtedness along with the analysis of the dynamics in the development of the main fiscal and debt instruments in the EU Member States enabled to draw the following conclusions.

The clear trend towards a reduction of the budget deficit, which in 2016 limited the public indebtedness by reaching up to and below the eligible 3% (except for Spain and France) lead us to the conclusion that the process of establishing fiscal adjustments, which found its normative expression in the Stability Pact, has an impact on the increase of the tax liability in the countries of the Community. Moreover, despite the imposed limitations of the applied model, the results of the regression analysis give us reason to conclude that the examined Member States demonstrate a trend towards economic and financial stability, which is a consequence of the consistent work of the Union to control the levels of indebtedness.

However, we question the extent to which the accordance with the Stability Pact requirements has an impact on the establishment of an effective budget policy in the EU Member States. Focusing only on the two main criteria (government debt and budget deficit) aims to separately assess the fiscal policy implemented by the Community’s Member States, but is not a sufficient condition for ensuring the sustainability of the ongoing economic processes in both the countries and the Union. It is equally important to formulate the prerequisites for stimulation of the economic growth and implementation of structural reforms according to both the specifics, tendencies and capacities of the individual economic systems and the development priorities of the EU. Last but not least, the question whether there is an economic effect and to what extent it is attributable to the existence and enforcement of supranational is consistent with the Union and remains within it requirements for fiscal discipline.

Balassone, F., Franco, D. (2000). Assessing fiscal sustainability: a review of methods with a view to EMU. Rome: Banca d’Italia. URL: https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/altri-atti-convegni/2000-fiscal-sustainability/021-060_balassone_and_franco.pdf?language_id=1

Balázs, É. (2015). Public debt, economic growth and nonlinear effects: Myth or reality? Journal of Macroeconomics, 43 (C), 226-238.

Bird, G., & Mandilaras, A. (2013). Fiscal imbalances and output crises in Europe: will the fiscal compact help or hinder? Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 16 (1), 1-16. URL: http://baobab.uc3m.es/monet/monnet/IMG/pdf/Fiscal_imbalances_and_output_crises_in_EU_Will_fiscal_compact_help_or_hinder_Bird_Mandilaras_2013.pdf

Blanchard, O., Dell'ariccia, G., & Mauro, P. (2010). Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 42 (1), 199-215.

Blavoukos, S., Pagoulatos, G. (2008). Fiscal Adjustment in Southern Europe: the Limits of EMU Conditionality. Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe, GreeSE Paper No 12. URL: http://www.lse.ac.uk/europeanInstitute/research/hellenicObservatory/pdf/GreeSE/GreeSE12.pdf

Buiter, W. H. (2003). Fiscal Sustainability. URL: http://www.willembuiter.com/egypt.pdf

Caner, M., Grennes, T., Koehler-Geib, F. (2010). Finding the tipping point - when sovereign debt turns bad. Policy Research working paper, no. WPS 5391. Washington, DC: World Bank. URL: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/509771468337915456/Finding-the-tipping-point-when-sovereign-debt-turns-bad

Cecchetti, S. G., Mohanty, M. S., & Fabrizio, Z. (2011). The Real Effects of Debt. BIS Working Paper No. 352. Basel: Bank for International Settlements. URL: http://www.bis.org/publ/othp16.pdf

Checherita, C., & Rother, Ph. (2010). The Impact of High and Growing Government Debt on Economic Growth. An Empirical Investigation for the Euro Area. ECB Working Paper Series No. 1237. Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank. URL: http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1237.pdf

Clements, B., Bhattacharya, R., & Nguyen, T. Q. (2003). External Debt, Public Investment, and Growth in Low-Income Countries. IMF Working Paper, WP/03/249. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. URL: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2003/wp03249.pdf

Draghi, M. (2012). A European Strategy for Growth and Integration with Solidarity. Paris: A conference organised by the Directorate General of the Treasury, Ministry of Economy and Finance – Ministry for Foreign Trade.

Dziemianowicz, R., & Kargol-Wasiluk, A. (2015). Fiscal Responsibility Laws in EU Member States and Their Influence on the Stability of Public Finance. International Journal of Business and Information, 10 (2), 153-179.

Easterly, W., & Rebelo, S. (1993). Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32 (3), 417-458. URL: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/34e4/a7cbf875d1c9715056929eb7c31d2235f955.pdf

European commission. (2017). Excessive Deficit Procedures – Overview. URL: http://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/economic_governance/index_bg.htm

Friedman, M. (1957). A Theory of the Consumption Function. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. URL: http://papers.nber.org/books/frie57-1

Friedman, M. (1960). A Program for Monetary Stability. New York: Fordham University Press. URL: http://0055d26.netsolhost.com/friedman/pdfs/other_academia/Houghton.1965.pdf

Friedman, M., Schwartz, A. J. (1963). A Monetary History of the United States. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. URL: http://press.princeton.edu/titles/746.html

Keynes, M. (1936). The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. New York, London: Harcourt, Brace and Co. URL: https://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/economics/keynes/general-theory/

Kotova, A. A. (2013). Features and effects of international integration of the financial markets. Contemporary Economic Issues, 1. DOI: 10.24194/11307. URL: http://economic-journal.net/index.php/CEI/article/view/43/31

Kotova, A. A. (2014). Conceptual provisions for the integration of the financial market in the world. Contemporary Economic Issues, 1. DOI: 10.24194/11403. URL: http://economic-journal.net/index.php/CEI/article/view/96/83

Krueger, An. (1974). The Political Economy of the Rent-Seeking Society. American Economic Review, 64 (3), 291-303. URL: http://cameroneconomics.com/kreuger%201974.pdf

Martinez-Vazquez, J, & Jameson Boex, L. F. (1997). Fiscal Capacity: An Overview of Concepts and Measurement Issues and Their Applicability in the Russian Federation. GSU Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Working Paper, No. 97-3. URL: https://ssrn.com/abstract=470821 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.470821

Mastern, I., & Gnip, A. (2016). Stress testing the EU fiscal framework. Journal of Financial Stability, 26, 276-293. URL: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S157230891630064X/1-s2.0-S157230891630064X-main.pdf?_tid=095d00e6-600f-11e7-b30e-00000aacb362&acdnat=1499100517_e453429c3609f9a9f42517e0d7d2a7f8

Ostry, D., Ghosh, A. R., & Espinoza, R. (2015). When Should Public Debt Be Reduced? IMF Staff Discussion Note, SDN/15/10. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. URL: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/sdn/2015/sdn1510.pdf

Patillo, C., Poirson, H., & Ricci, L. (2002). External debt and growth. IMF Working Paper, WP/02/69. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. URL: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2002/wp0269.pdf

Savage, J. D. (2001). Budgetary Collective Action Problems: Convergence and Compliance under the Maastricht Treaty on European Union. Public Administration Review, 61(1), 43-53. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/977535

Spencer, R. W., Yohe, W. P. (1970). The 'Crowding Out' of Private Expenditures by Fiscal Policy Actions. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 12-24. URL: https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/70/10/Expenditures_Oct1970.pdf

Treaty on European Union. (1992). Brussels: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, ISBN 92-824-0959-7. URL: https://europa.eu/europeanunion/sites/europaeu/files/docs/body/treaty_on_european_union_en.pdf

1. D. A. Tsenov Academy of Economics, Svishtov, Bulgaria. E-mail: r.lilova@uni-svishtov.bg

2. D. A. Tsenov Academy of Economics, Svishtov, Bulgaria. E-mail: a.radulova@uni-svishtov.bg

3. D. A. Tsenov Academy of Economics, Svishtov, Bulgaria. E-mail: a.alexandrova@uni-svishtov.bg