Vol. 38 (Nº 51) Year 2017. Page 29

Ardak KAPYSHEV 1

Received: 28/09/2017 • Approved: 09/10/2017

3. Data, Analysis, and Results

ABSTRACT: The purpose of this article is to study the features of Germany’s image formation among Russian Germans. In the course of the study, we have used a method of comparative analysis. The specific nature of Germany’s image was characterized with methods of primary data collection and processing, and with comparative methods of systematization and logical generalization. The article analyzes the image of Germany through the eyes of Russian Germans. The analysis showed that the image of Germany that was formed among Russian Germans is not transformed. It is still at the stage of formation, not always overcoming xenophobia. There are analyzed and generalized the main characteristics of the ethnic image of Germans. Thus, we have found that if the respondent does not intend to move to Germany, then there often will be negative and neutral elements prevailing in the image of the country. In the case of moving – a more positive image of Germany is formed. The new image of a new country to live in (Germany) can be described as follows: it is a familiar, quiet, comfortable and socially stable country with a favorable economy and stable legal framework. The weakening economic situation and the growing unemployment are the only disturbing facts, as well as a rather closed social space. |

RESUMEN: El propósito de este artículo es estudiar las características de la formación de la imagen de Alemania entre los alemanes rusos. En el curso del estudio, hemos utilizado un método de análisis comparativo. La especificidad de la imagen de Alemania se caracterizó por los métodos de recopilación y procesamiento de datos primarios y por métodos comparativos de sistematización y generalización lógica. El artículo analiza la imagen de Alemania a través de los ojos de los alemanes rusos. El análisis mostró que la imagen de Alemania que se formó entre los alemanes rusos no se transforma. Todavía está en la etapa de formación, no siempre superando la xenofobia. Se analizan y se generalizan las principales características de la imagen étnica de los alemanes. Por lo tanto, hemos encontrado que si el demandado no tiene intención de mudarse a Alemania, a menudo habrá elementos negativos y neutrales que prevalecen en la imagen del país. En el caso del movimiento - se forma una imagen más positiva de Alemania. La nueva imagen de un nuevo país para vivir (Alemania) se puede describir como sigue: es un país familiar, tranquilo, cómodo y socialmente estable con una economía favorable y un marco legal estable. El debilitamiento de la situación económica y el creciente desempleo son los únicos hechos perturbadores, así como un espacio social bastante cerrado. |

In the context of political changes of the ХХ and early ХХІ centuries, deepening inequality of countries in terms of well-being, wars, environmental disasters and other phenomena, international migration has emerged as a complex global problem affecting the interests of all countries in the world. At the global level, international migration is increasingly considered as an integral part of the global development process. Over the past 2-3 decades, Germany is one of the countries in which residents from other countries are actively resettling (Вetter, 2011).

The intensified resettlement in Germany began immediately after the reunification. Nearly 100 thousand people were leaving the new federal lands every year. Democratic changes in Central and Eastern Europe, and the collapse of the Soviet Union caused massive flows of asylum seekers, illegal migrants and repatriates. In five European countries (Belgium, Great Britain, Germany, Netherlands, Sweden), the average annual migration balance has increased from a negative figure of -13,000 people (in 1980-1984) up to 456.000 (in 1985-1989) and 784.000 people (in 1990-1994) (Hess, 2016).

In EU member states, the number of asylum applications has increased by 487% in 1986-1991 – almost 700.000 applications per year. In Western European countries, this number has increased from 66.9 thousand (in 1983) to 694 thousand applications (in 1992). In 1983-1989, 30% of applications were from the countries of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union (Stalker, 2002). The period after 1990s was characterized by an even greater scale and intensity of migration flows. At the same time, dynamics of migration from the former Soviet states has declined (Hess, 2016).

The significant increase in the number of immigrants from Russia has affected the image of Germany among the German residents in Russia, as they receive certain information about life in Germany from relatives and friends, who have moved there. Moreover, they have own vision of their future in Russia as German people, or plan to move to Germany in the future. This actualizes the issue of determining the specific features and the main aspects of Germany’s image formation among Russian Germans.

Modern researchers studying the category of citizenship distinguish the territorial and national principles of State organization and citizenship acquisition (Mathias, 2013). The second case is regarded as a more closed "to enter" into it, and therefore, less attractive for migrants (Kunze, 2005). Nevertheless, many researchers draw attention to the dynamics of the number of foreigners in Germany at the end of the 20th century. It shows that the country was attractive for migrants and provided legal opportunities to stay in Germany and acquire a German citizenship (Bauder, Lenard & Straehle, 2014). In particular, we should point out the following studies devoted to the issues of migration to and from Germany written by such authors as Bauder, Lenard & Straehle (2014), F. Triadafilopoulos (2015) and M. Tackle (2007).

In studying the work of modern authors, we can state (Hess, 2016; Triadafilopoulos, 2015) that the immigration policy of the country is the subject of acute public discussions. There should be noted the relevance of discussing the issues of multiculturalism formation or destruction in Europe due to specific legal actions (Triadafilopoulos, 2015; Winter, 2014) influx of emigrants from Muslim countries and countries with a significant difference in cultural and social behaviours (Gülhanim, 2015).

Migration and integration of population are processes. Thus, they are in constant movement and change. Constant monitoring of these processes is absolutely necessary and requires such kind of a combined scientific theoretical and sociological research.

The issues of Russian-speaking population living outside Russia that are important for understanding the specific features of Russian Germans’ adaptation in specific life conditions are reflected in (Ryazantsev, 2015). The work of modern scholars devoted to the adaptation of emigrants from the former Soviet countries, in particular – from Russia, in Germany are of prime importance for the study (Penny & Rinke, 2015). However, these works have a significant shortcoming – they ignore the difference in Germany’s image formation among those Russian Germans, who live in Germany and outside it.

The purpose of the article is to study the features of Germany’s image formation among Russian Germans.

In identifying the features of Germany’s image formation among Russian Germans, we have used comparative analysis as a research method. This made it possible to reveal the differences, peculiarities and common features of perception of Germany by the inhabitants of this country, by Germans, who moved to Germany from Russia, and by Germans living in Russia.

Based on migration intentions, analysis of the Germany’s image formation among Russian Germans was studied with a methodological base and study materials of the Centre for German and European Studies (CGES), Bielefeld (Germany) and St. Petersburg Universities, and the RFBR Grant 06-06 -80166-a "Ethnic factor of socio-economic transformation of rural areas in multi-ethnic regions of Russia". This work considers certain methodological scientific developments and publications of domestic and foreign scientists on the problems of Germany’s image formation among Russian Germans (Hess, 2016; Ryazantsev, 2015), as well as current legislative and regulatory documents. The specific features of Germany’s image formation among Russian Germans were analyzed and characterized by methods of primary data collection and processing, and by comparative methods of systematization and logical generalization.

According to the annual migration report of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), Germany is in the top-five of the most attractive countries for migrants in Europe [18]. It has been a leader in external migration for 10 years. According to migration balance for 10 years, the first places are taken by Italy (3281 thousand people); Spain (2560 thousand people) and the United Kingdom (1959 thousand people). Germany is on the fourth place – 1410 thousand people.

In 2015, a total of 2.137 million people moved to Germany. This number is bigger by 672.000 than it was in 2014 (46%). In the same year, only 998.000 people moved from Germany. The recorded number is bigger by 83.000 than it was recorded in 2014 (+ 9%). This results in a migration surplus of 1.139 million people, which is a new record of the FRG (Migrationbericht, 2014). The increased influx of migrants in Germany in 2015 is associated with an increased immigration of foreigner citizens. The number of Germans, including ethnic Germans and repatriates, was about 121.000 people and remained almost unchanged in comparison with the previous year. In 2015, the 998.000 migrants from Germany included 859.000 foreigner citizens and 138.000 Germans. In the arrival-and-departure balance, this entails a net immigration of foreigner citizens (1.157.000 people) and a decreased migration of German citizens (18.000 people).

About 45% of immigrants were citizens of the EU member states, 13% – of other European countries, 30% – of Asian countries, and 5% – of African countries.

In 2015, all German states had a positive migration balance with foreign countries. Nevertheless, almost three-quarters of immigrated foreigners settle only in five states: the migration surplus was particularly high in the North Rhine-Westphalia (277.000 people), Baden-Württemberg (173.000), Bavaria (169.000 people), Lower Saxony (115.000 people) and Hesse (95.000 people) (Migrationbericht, 2014).

Thus, based on the current situation, there was a situation when the percentage of non-citizens living in Germany for a long time or even from birth was significant among the German foreigners (about 1/3) by the beginning of the XX century. However, they remained as "foreigners" in German statistics and public discourse (Flam, 2007). The foreign population of Germany increased from 506 thousand to 7 million people from 1951 to 2005 (in 14 times) (Table 1, based on (Migrationbericht, 2014)).

Table 1 – Number of citizens and non-citizens of Germany in1951-2015

|

Total population |

Number of citizens |

Number of non-citizens |

||

thousand of people |

thousand of people |

% |

thousand of people |

% |

|

1951 |

50808,9 |

50302,9 |

99,0 |

506,0 |

1,0 |

1961 |

56174.8 |

55488.6 |

98.8 |

686.2 |

1.2 |

1971 |

61502.5 |

58063.8 |

94.4 |

3438.7 |

5.6 |

1981 |

61719.2 |

57089.5 |

92.5 |

4629.7 |

7.5 |

1990 |

63725.7 |

58383.2 |

91.6 |

5342.5 |

8.4 |

1991 |

80274.6 |

74392.3 |

92.7 |

5882.3 |

7.3 |

1996 |

81881.6 |

74567.5 |

91.1 |

7314.1 |

8.9 |

2005 |

82501.0 |

75801.0 |

91.9 |

6700.0 |

8.1 |

2015 |

81413.0 |

74400.0 |

91.4 |

7013.0 |

8.6 |

The dynamic postwar economic development, an advantageous location and "humane" social policy quickly transformed the FRG from a country with an emigrant "image" into an object of foreign citizens’ attention. Foreigners have become a serious factor in the country's current economic development. They own 281 thousand of firms (6.3% of all enterprises registered in the country in 2005). Turks are leaders in the business sector. They own 22.9% of foreign-owned enterprises (Bommes, Castles & Wenden, 1999).

Thus, 7 million people, \considered as foreigners, de facto are not foreigners, but not citizens either. As often happens, this situation has two "truths". The first explains the situation as follows: the state with a significant migration gain had not been describing it in terms of international migration for a long time. The resettlement of ethnic Germans was considered as a return home until the late 80's. They received the civil status documents in no time ("automatically") and were blended into the category of "population" almost immediately. By the mid-1990s, public space was enriched by new categories– "Russian Germans" and "Eastern Jews". Although the arrival of both was described by different terms ("late resettlers" and "contingent refugees", respectively), it gradually began to be called the "migration from the Eastern Europe countries ". Old non-citizen residents are, in fact, those migrants, who migrated to Germany on the wave of German labor immigration in the 1970s. Namely, they have moved after the closure of "temporary labor resettlement programs" due to the so-called chain reaction. Ascribed status of "nonimmigrant state" did not bind the country to initiate the granting of citizenship to this group of people in any way.

The beginning of the 1990s was a peak period of resettlement from the former Soviet states. In 1990, about 400 thousand of people arrived to Germany. In 1988-1998, the country received slightly more than 3 million of settlers. German villages and places of compact residence have disappeared in Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine by the end of the 1990s. Some experts call this “flight to nowhere”: Russian Germans had no idea of where they were going and what awaits them in their historical homeland. However, it seemed impossible to stop the chain reaction. Serious problems of immigrant integration into German society have arisen already by the mid-1990s. The fact is that most of them did not know German at all. In July 1996, the so-called language tests were introduced into the immigrant reception procedure. They have become an obstacle for many ethnic Germans on their path to their historical homeland.

In 2000, the number of migrants did not exceed the mark of 100 thousand people for the first time. In 2005, this indicator has stabilized at the mark of several thousand per year and remains like that to this day. For example, about 6 thousand immigrants arrived to Germany. At the very beginning of the mass resettlement of ethnic Germans to their historical homeland (in 1988), German government decided to create a special department under the Ministry of Internal Affairs and an authorized immigration center.

Three million immigrants integrated in Germany in 20 years is a result of great efforts. The figure of three million immigrants is comparable to the population of one medium-size federal state in Germany. This figure is more than the number of inhabitants in Thuringia or Brandenburg (Rys, 2008).

Settlers are not only the most numerous group of migrants. They are better than representatives of other categories, integrated into German society. Albert Schmid, the President of the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees, whose competence lies in the integration of nonresidents, emphasizes that, according to statistics, the unemployment rate is much lower among immigrants than among the native inhabitants of Germany. The problem group still includes the qualified specialists – doctors, teachers and engineers (Santel, 2007). The stumbling block still is the low level of German language proficiency, in particular technical language proficiency, which is necessary for communication not only among colleagues, but also patients, clients and students.

Nevertheless, there are many settlers (scientists, athletes, Olympic champions, artists and musicians) who have successfully integrated and became famous throughout the country.

The settlers work at the factories, hospitals, educational institutions; they also start own businesses. In addition, they carved out a niche in the sphere of life and service. In Germany, there are many Russian-speaking tourist offices and agencies, beauty and hairdressing salons, restaurants and nightclubs. One can find newspapers and journals published in Russian, Russian-language theaters, concert agencies that spice the cultural exchange between Germany and the CIS countries. That is why the German politicians, including the Chancellor of Germany, assign the settlers and Russian Germans the role of living bridge in Germany's dialogue and cooperation with Russia and other post-Soviet republics (Seydakhmetova, 2016).

The share of foreigner citizens in the country's population, constantly increasing in the second half of the 20th century, began to fall for the first time since the beginning of the new century because of two primary reasons – reduced immigration flow and increased number of cases when people were granted with German citizenship. According to M. Böhmer, the Commissioner for Migration, Refugees and Integration of the FRG, more than a million of foreigner citizens were granted with a German citizenship in 2000-2005 (Bnews, 2016).

Based on the annual emigration, which was recently about 600 thousand of people per year (mostly foreigners), positive net migration is more than 200 thousand of people. This figure is almost in 3 times lower than it was a decade ago. Her data indicate that about a quarter of it are Germans, who migrate from one country to another (Consulate General of Germany in Almaty, 2017).

The ethnic Germans’ departure from the former Soviet Union to Germany was the most powerful and organized migration flow of the collapsed empire. This is understandable, because unlike an unorganized migration of many other former Soviet citizens in search for a better life, Germans' relocation to Germany was a result of a purpose-oriented state policy of this country.

The creation of favorable environment for the immigration of Germans from the Soviet Union had a serious political implication. At the same time, German government did not take into account the resettlement costs and the difficulties of integrating such a mass of former Soviet citizens into the German reality. German politicians will become aware of the scale of "Russian Germans" problem later. However, this process was so important for Germany that all costs were considered as insignificant at the beginning of the great journey of Germans from East to West.

However, political reasons still prevailed over others, including moral obligations. There were created super-favorable conditions for the Soviet Germans to immigrate. At the same time, ethnic Germans from Brazil and Argentina, who wanted to move to Germany, had no special advantages over other foreigners. The Germans explain this by the fact that Soviet Germans immigrated by virtue of the Federal Law on Refugees and Exiles. According to this law, Germany supported those Germans, who were expelled from Czechoslovakia, Poland and East Prussia after the World War II.

The support for Soviet Germans’ immigration was of particular importance for the "Unions of Expellees" as it was a sign of solidarity with people, who became a victim in the framework of collective responsibility of German people for the Nazi crimes. Soviet Germans were forcibly placed in labor camps during the war, where the so-called "labor armies" were formed. In addition, Soviet Germans were forcibly relocated from the European part of the Soviet Union to its Asian part.

It can be stated that German leadership had own political goals in Germans’ immigration from the Soviet Union. The majority of German population considered this act as a helping hand that the country should lend to compatriots in distress. This gave a great impetus for Germans to move from East to West. Thus, the process has started.

Former Soviet Germans make up the largest Russian-speaking group in Europe. They are responsible for the often changing appearance of German cities: many Russian stores, dozens of newspapers in Russian, Russian-speaking travel agencies, dental clinics, chemist’s shops and auto repair shops. In truth, satisfying the demand of two million of "Russian" Germans and the 400.000 of other immigrants from the former Soviet Union is a good business.

The situation of former Soviet (now "Russian") Germans is unique as they are in some ways wearing two hats in a time. On the one hand, they are typical immigrants, creating a special isolated group of population, as Turks, Italians, former Yugoslavs, Albanians, Africans and Romanians do. On the other – they are citizens of Germany. This duality creates many problems both for the "Russian" Germans themselves and for the State.

In Germany, they assumed that they would have no problems with the integration of "Russian Germans" into the life of German society. The authorities did everything at the first sight: taught the immigrants the German language, tried to settle them evenly across the country in order to prevent the enclave formation, provided them with a German-like standard of living and financed programs to draw their children and the local ones together. Everything what was done seems to be correct, but eventually they got a unique situation.

In Germany, there was formed an isolated group of people, who are full-fledged citizens, but not integrated into German society as it was planned (John & Klaus, 1994). This group has actually formed a community that is alien to German values, continues to use Russian language for communication and begins to actively change the life environment (Seydakhmetova, 2016). The latter is the most unpleasant for Germany.

Moreover, the German government did not expect the "Russian" Germans to turn into a serious burden for the budget. The social spending was too excessive, while more than a million migrants prefer to scrounge off the state using various social programs for their support. Many settlers are sitting pretty on the platform of the so-called "welfare system". This is approximately EUR 250 for the head of the family per month and smaller amounts for the rest of the family. In addition, the State pays for the part of an apartment – 50 square meters for the head of the family and a smaller amount (15, 10 square meters) for each next member of the family. This had to be a temporary measure until "Russian" Germans assimilate in Germany. However, this moment was never seen since then.

Germany simply did not take into account the specific features of Soviet mentality. Germany offered the Russian Germans conditions that they simply could not refuse after the collapse if the Soviet Union, the most difficult period of the state structure breakage. Thus, Russian Germans moved from under the wing of one caring, but collapsing, state under the wing to another, more generous and rich. Namely, they changed the Soviet paternalism to the German paternalism, and calmed down.

Russian Germans avoided the problems that were in Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine, where people had to learn how to survive in market conditions and to fight for a place in the sun. Besides, they sincerely believe that they have been lucky in their lives as compared to the population of the CIS countries. They even feel sorry for us. This can be understood. As a Soviet man, one considers the situation as a right way for it to be. Anyone who could find a place more satisfying (in a barrack, in a shop warehouse or in Baltic States and Belarus that are richer in comparison with the hungry Russian Non-Black Earth Region) felt as a winner. The German government was in the worst situation as it got a social group of people, who had a parasitic attitude in life and believed that Germany owned them something. The majority of Russian Germans does not understand the market logic of life, according to which one should not expect help from a good man, but do everything by oneself. The most important thing is that our market allows the active population to run own business. Therefore, we have to feel sorry for these Germans as they hung between two worlds, two ways of life (MFA of Kazakhstan 2010).

Vertriebene, Aussiedler, Spätaussiedler – this is how Germans call the immigrants from Russia, who moved to Germany by virtue of the Article 116.1 of the German Constitution. Naturally, their grandfathers and fathers suffered much more from their belonging to German people than the next generation. After all, they were direct participants of the great migration, when all Germans living in Russia and Ukraine were forcibly relocated to Kazakhstan and Siberia in August 1941, according to Stalin’s order. Everyone, who was older than 16, was sent to the so-called labor army – concentration camps for the enemies of the people with inhuman conditions of existence. In 1957, Germans were rehabilitated, but many of them stayed in Kazakhstan or Siberia because there was nowhere to go back. The German Autonomous Republic, established by Lenin’s decree, no longer existed, houses built by Germans were taken from them, and they had nowhere to go. In the period of publicity, it became possible to move to Germany. Actually, it was always possible on the part of Germany because its Constitution had a line stating that any German living outside Germany has the right to move to Germany at any time. Thus, the problem of choosing a federal state for living, work and education became urgent after the resettlement of ethnic Germans (MFA of Kazakhstan 2010).

In April 2007, higher education became for-profit in five federal states. In October, they were joined by two more states. However, most universities have provided benefits for certain categories of students (Bnews, 2016). Like many other European states, modern Germany is between two fires. Authorities have to attract migrants because of a little working-age population and the problem of aging in the context of depopulation. At the same time, they do not want to accept new setters due to national, social and other reasons.

Actually, different facts do confirm the serious demographic problem that emerged in Germany in the second half of the 20th century. Although the current macroeconomic, social and spatial situation in the country is tricky, there is a position that demographic problems are the most important to consider. On the other hand, immigration restriction seems understandable for a number of reasons. However, Germany’s ruling parties and authorities are forced to "adjust" to the mood of society as any other. These "adjustments" become particularly obvious at the end and the beginning of each political cycle.

1. Officially, Germany was not an immigrant country until the end of the twentieth century: there were no statutory regulations on immigration and/or migration policy, except the concept of "repatriation".

2. In the 1970s, there was a conflict between politics and everyday administrative practice – the state, officially not accepting immigrants, institutionalized various types of migration.

3. There was a position of moral reparation of German national history in relation to the Jews that resulted in a program of Jewish immigration. It has a significant impact on the real immigration picture of the country.

4. According to the German Constitution and the Federal Law on Refugees and Exiles (1953), all Germans, who were exiled from their native land in the 1940s and lived in the former German eastern lands or outside Germany (including the Eastern European countries and China) by May 8, 1945, have the right to repatriate to Germany. In fact, they have the right to immigrate.

5. Germany is a main player in European integration and an undoubted participant in globalization in general. The growing internationalization of production and distribution of labor markets enjoin the state upon active participation in the migration processes. Freedom of movement within the EU and the EEA predetermines a significant international labor exchange with their Eastern European members before and after a certain transition period in joining the EU. However, "nothing is more permanent than the temporary". Temporary labor migration not always, but often turns into migration to a permanent place of residence. Modern Germany knows about these "transformations" more than other European countries.

6. The requirements of domestic labor market (primarily, the structural ones) become more and more important. Certain industry segments do not cope with the existing load and need the inflow of specialists from the outside. We do not mean the most highly qualified specialists of the leading knowledge-intensive industries. It is all about the tertiary activity. Each of these positions imposes its limitations and demands on the modern immigration policy of the country. In modern Germany, there are two categories of population: Germans and foreigners (92% and 8%, respectively) (Bnews, 2016).

The standard of living of 15 million migrants, living in the FRG, has not been improved lately. According to statistics, they are losing their jobs and committing crimes twice as likely in comparison with the main population. The situation of immigrants, living in Germany, has not been improved recently as they are twice as likely to face unemployment and poverty in comparison with the natives. The crime rate is also about twice as higher among immigrants, whose share was about 15 million people at the end of 2007. In 2007, it was 5.4% among the migrants. This is twice as high as the crime rate among natives. At the same time, this figure reached 12% among young people at the age of 14-17 in comparison with the figure of 7.8% among the entire German population of the same age (Gagerow, 2010). In 2007, the unemployment rate was 10.1% among the entire German population 20.3% among the migrants. There are much more poor people among the newcomers than among Germans. In 2007, only 9.5% of Germans received a social assistance benefit, while the share of migrants was 20.3% (Facts about Germany, 2015).

Experts of the Hamburg Institute of International Economics (HWWI) and the Pricewaterhouse Coopers have conducted a study to measure the in-migration rates and to find out how they affect the Germany development. The results were quite predictable: population of the metropolitan area in the west of the country will continue to increase. According to scientists, Cologne is one of the most attractive cities in Germany due to its favorable location (proximity to France and Benelux countries) and well-developed infrastructure (Rys, 2008). Economists believe that the employment level will increase by 30% by 2018. Munich has positive prospects – the number of jobs is projected to increase by 12%. According to the researchers, the western part of the country is still attractive for many residents of the new federal states, including those, who have a job, because many eastern companies are not able to provide the same wages as the western ones. Moving in the opposite direction is much less frequent. Although some Western Germans use an opportunity of moving to the eastern regions as a launch pad for own career, the majority of people, living in the old federal states, still consider it from the point of negative stereotypes (Heimat-Родина, 2008). Thus, eastern regions of Germany (rural areas and certain western areas of the country) are under the threat of depopulation. According to the forecasts, working-age population will reduce in the 99 of 429 (including 61 in the east) regions and cities under the district’s jurisdiction by 2018 (Heimat-Родина, 2008).

At the same time, there are positive examples of how to avoid the "brain drain" and "labor force losses". Authorities managed to turn the outflow of specialists back to such cities as Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden. The experience of the latter is particularly interesting: more than 20.000 new jobs have been created here in more than 750 new enterprises in the HT sphere. Over the past decade, the capital of Saxony State managed to hit the world's top ten major centers of microelectronics. The successful experience in Jena, where the number of highly skilled workers will grow by 11%, according to forecasts for 2018, is also illustrative because the city used its available potential. Namely, authorities paid no less attention to local university development then to the well-known Carl Zeiss Jena enterprise, and they did not forget about the interests of city residents (Reißlandt, 2005).

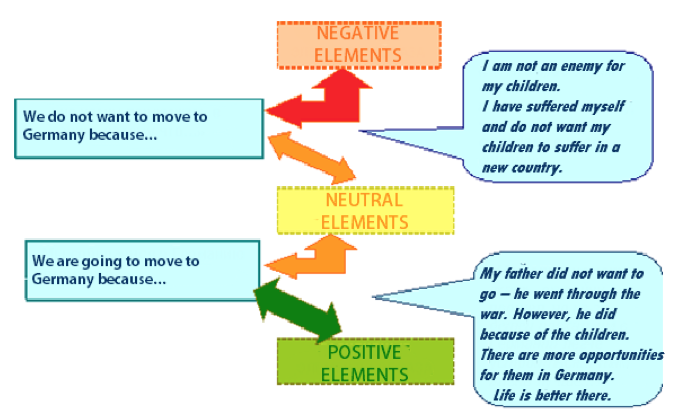

Let's consider the mechanism of Germany’s image formation in more detail – in terms of migratory desires of Russian Germans. The interview and its analysis showed that if the respondent does not intend to move to Germany, then negative and neutral elements will often prevail in the image of the country.

If the decision to move is already taken, a more positive image of Germany is formed. It is interesting that respondents have used the same reasons in both cases: "I'm going/not going because ... there's no work there/here, the life here/there is easier". Children are the most common reason why respondents leave or stay in the country (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Germany’s image formation among Russian

Germans based on their migratory desires

Note – [Study materials of the Centre for German and European Studies (CGES), Bielefeld (Germany) and St. Petersburg Universities (supported by the RFBR Grant 06-06 -80166-a)]

Below are the most typical moments from the interview that illustrate the negative image of Germany is aggravated depending on the migratory desires:

The way of thinking is transformed after moving to Germany. Based on the interviews with the settlers, we have identified the main directions of Germany’s image transformation among Russian Germans after their migration (Table 2).

Table 2

Germany’s image transformation among

Russian Germans after moving to Germany

Germany in the eyes of Russian Germans |

||||||

In Russia |

In Germany |

In Russia |

In Germany |

In Russia |

In Germany |

|

Neutral Features |

Positive Features |

Negative Features |

||||

Urban culture |

|

Discipline and accuracy |

|

Deteriorating economic situation - unemployment |

||

Different nature |

|

Cleanliness - well-adjusted life |

Negative attitudes towards newcomers |

|||

Historical homeland |

High level of culture - civilization |

There are many foreigners, including Russian people |

|

|||

Everything goes in small sizes |

It is a religious country |

|

Lack of communication |

Boredom |

||

Restful atmosphere |

Prosperity |

Too much freedom, free-for-all approach, lack of upbringing |

||||

|

|

Social protection |

No communication with nature |

Cold and soggy weather |

||

It’s a free country |

It is a law-abiding country |

|

There is no legal freedom for action |

|||

|

It feels like home here |

It is a country of individualists |

||||

|

|

I thought it was a religious country, but it turned out to be not a religious one |

||||

I thought it was a clean country, but it turned out to be a lie |

||||||

Note – [Study materials of the Centre for German and European Studies (CGES),

Bielefeld (Germany) and St. Petersburg Universities (supported by the

RFBR Grant 06-06 -80166-a)]

In neutral images, such features as urban culture and different nature are less common, the following neutral features remain: historical homeland, everything goes in small sizes, restful atmosphere. Certain features that respondents considered as neutral in Russia are often considered as negative after moving to Germany. This is distinguishing in relation to the nature of a new country. In Russia, the majority of respondents, speaking about the nature in Germany, often spoke of it being different. After moving to Germany, many people note the lack of Russian spaces and no freedom to walk in the forest; chamber environment irritates the respondents (Savoskul, 2006).

The majority of respondents indicate habituation to a new country as a general feature of a neutral image. Thus, the key word changes from "everything different" to "everything habitual". Certain positive features of the Germany’s image disappear in the mind of Russian Germans and their family members after moving to Germany. This happens most likely because they stop being unusual and new and partly because these expectations are not been met. These features are cleanliness, well-adjusted life and a high level of culture. Certain positive features (or rather their lack-describing manner) that were attributed to Germany before migration, but turned out to be not equal to expectations after moving, become to be considered as negative ones, aggravating the negative image of the country. Below are the most impressive examples from the interviews with Russian Germans in Germany:

"... I thought that Germans were all religious and God-fearing people; that no one can do wrong in Germany because I was the same god-fearing man in a young age. But it turned out to be ... Well, I first-ever saw that women walk and smoke openly, and blah-blah-blah..."

"They said that the roads here are washed with soap. Everything is very clean, nothing can be done. People earn good money here. But, when I got out of the plane, I was surprised, even kind of frightened... There was a lot of paper, garbage. That never happened in Uzbekistan... " (Savoskul, 2006).

The positive features noted by Russian Germans in Russia, but becoming even more significant after migration, head our list. These are prosperity and social protection. Respect for the law and the feeling of a strong state are new important positive elements. These features are the basis of a positive Germany’s image among the settlers and the key word that was mentioned by Russian Germans in Russia. Thus, a romantic image of Germany – "stability-home" – becomes more realistic ("material prosperity-law)".

The negative features were transformed even harder among the settlers. The negative image becomes more vague and paradoxical; there are often mutually exclusive statements. For example:

«... we went here because we were not protected in Russia, but it turned out that they were not very protected here either. Try to stand on own feet ... ».

Features that are definitely negative remain unchanged in relation to the economic and social well-being of the country. This was noted by Russian Germans during their interviews both in Russia and in Germany. These features are: deteriorating economic situation and the increasing unemployment rate. As a result, negative features of the Germany’s image have transformed from the "one is better, but boring", to more a detailed and sketchy "Things are more complicated" (Savoskul, 2006).

The previous image of Germany among Russian Germans in Russia, which was mentioned above, is changed to a new image of a familiar country after migration. In the eyes of Russian Germans in Russia, Germany is a country of ancestors, a country with a high level of culture, a prosperous economic and social situation. It is a clean country with a settled life and material well-being not overbalancing the social isolation. The new image can be described as follows: it is a familiar, quiet, comfortable and socially stable country with a favorable economy and stable legal framework. The weakening economic situation and the growing unemployment are the only disturbing facts, as well as a rather closed social space.

The Russian diaspora in Germany consists mostly of migrants, who arrived from the former Soviet states with the last (fourth) emigration wave, and of emigrant descendants. The latter category takes roots from the first, second and third waves of Russian emigration. Russian and German population have common features: language, culture, origin, spiritual and religious life. Generally, this corresponds to the main results of modern studies (Fenicia, 2016).

In this case, we have to take into account the major behavioral features of German citizens, who have and do not have citizenship, as it was studied in (Shabayev, Goncharov & Sadokhin, 2016). This behavior can manifest itself differently in different social groups at a gender and professional levels. This was highlighted in (Iarmolenko, Titzmann & Silbereisen, 2016) and in (Hess, 2016). The latter is devoted to behavior affecting the issues of public policy and management.

Thus, the Government of the FRG has been taken many measures to support migrants. Initially, the Government hoped that immigrants would assimilate in Germany and would not differ from others. This was a long-term investment in human capital. However, nothing has changed after several decades. Migrants were still "being fed with a spoon" by the Republic. However, it should be noted that the new generation of "Russian Germans" differs significantly from their parents. In school/university, they feel a significant difference between the native Germans and their parents. The new generation is more inclined towards the native Germans, because they do not understand that one can live on benefits, not work, not study, do not achieve anything.

The state weakened the support of migrants in Germany during the economic crisis and after it. This caused discontent on the part of ethnic Germans from the former Soviet Union. In our opinion, this was an act of disrespect to the country in which they live, which literally feeds them.

Nevertheless, balancing the interests of immigrants (especially in the labor sphere), the anti-immigrant public and the "social state" (basic democratic and socio-economic orientation) remains to be the most important task. Readiness of authorities to adhere to the developed strategy without changing the solution on an annoyingly regular basis, as it was in Germany in recent years, is an equally significant success. In Germany, the "social city" is much older than the "social state" from a historical point of view.

We assume that the Germany’s image is not transformed among Russian Germans, but is still only at the stage of formation not always overcoming xenophobia. The main characteristics of the ethnic image of Germans that arose in the interviews can be reduced to the following pairs (from a positive to a negative image):

This image was formed under the concrete and quite tangible problems related not only with the language ignorance, but also with employment, citizenship, natives’ attitude, etc. This is not a complete list of problems the settlers face.

According to the study, we can assume that the new image of a new country to live (Germany) can be formulated as follows. It is a familiar, quiet, comfortable and socially stable country with a favorable economy and stable legal framework. The weakening economic situation and the growing unemployment are the only disturbing facts, as well as a rather closed social space.These conclusions confirm and illustrate the D. Zamyatin's conclusions about the impact of migration on how the migrants perceive the new country.

Thus, in the second half of the XX century, Germany as an emigrant country turned into an immigrant country and became the leader by the number of immigrants in Europe (more than 1/3 of all EU migrants and 2/3 of all migrants from Central and Eastern Europe). The approximate calculations show that the country “took on board” 13 million people (net migration gain) in 1950-2015. Despite this generally favorable picture, Germany's real migratory "history" is not so unambiguous: periods of large gains were followed by recessions. Thus, even a peek at the net migration curve makes it easy to "read" the "migration wave", which oscillation amplitude is reducing from year to year. Despite the numerous and constantly reorganizing immigration legislation and institutions, its spheres are always clearly distributed between levels and specific structures.

Migration has a significant impact on the Germany’s image transformation among Russian Germans, who do not have German citizenship, but who live in there. It also has a significant impact among those Germans, who live in Russia and do not plan to migrate to Germany. It determines the nature and results of the ethnic image formation of Germans among Russian Germans. The spectrum of neutral image features is narrowing due to migration. This process entails specification of the positive ones. The majority of respondents have a detailed vision of what is Germany like, while the image becomes more fragmented.

In considering the image of Germany through the eyes of Russian Germans, we have determined that the image of Germans is not transformed, but is still at the stage of formation. We have found that if the respondent does not intend to move to Germany, then there often will be negative and neutral elements prevailing in the image of the country. In the case of moving – a more positive image of Germany is formed. The new image of a new country to live in (Germany) can be described as follows: it is a familiar, quiet, comfortable and socially stable country with a favorable economy and stable legal framework. The weakening economic situation and the growing unemployment are the only disturbing facts, as well as a rather closed social space.

Bauder, H., Lenard, P. T., & Straehle, C. (2014). Lessons from Canada and Germany: Immigration and Integration Experiences Compared-Introduction to the Special Issue. Comparative Migration Studies, 2(1), 1-7.

Вetter Kz. (2011). New style of the Iron/Rubber Curtain. Why is the West against the “political emigrants” from the CIS countries? (in Russian) [Electronic recourse]. Assess mode: http://www.centrasia.ru/newsA.php?st=1305865260

Bnews. (2016). German Legal Environment. [Electronic recourse]. Assess mode: http:// -germanii-v- today.kz/blog/policy/god kazaxstane

Bommes, M., Castles, S., & de Wenden, C. W. (Eds.). (1999). Migration and social change in Australia, France and Germany. Institut für Migrationsforschung und Interkulturelle Studien (IMIS), Universität Osnabrück.

Consulate General of Germany in Almaty. (2017). [Electronic recourse]. Assess mode: http: // www. almaty.diplo.de

Facts about Germany. (2015). Standard of living of 15 million migrants. [Electronic recourse]. Assess mode: http://www.tatsachen-ueber-deutschland.de/ru/society/main-content-08/immigration-and-integration.html

Fenicia, T., Kaiser, M., & Schönhuth, M. (2016). Stay or return? Gendered family negotiations and transnational projects in the process of remigration of (late) resettlers to Russia. Transnational Social Review, 6(1-2), 60-77.

Flam, H. (Ed.). (2007). Migranten in Deutschland: Statistiken, Fakten, Diskurse. UVK Verlagsgesellschaft.

Gagerow, D. (2010). Education and Employment. What are the prospects?. THEMA. 13-24.

Gülhanim, C. (2015). An Epistemology of “The Other” and Othering: Narrative Analysis of Everyday Encounters. Narrative Works. 46-59.

Heimat-Родина. (2008).Patriotism or egoism – it is our call. [Electronic recourse]. Assess mode: http://www.heimat-rodina.de/

Hess, C. (2016). Post-Perestroika Ethnic Migration from the Former Soviet Union: Challenges Twenty Years On. German Politics, 25(3), 381-397.

Iarmolenko, S., Titzmann, P.F., Silbereisen, R.K. (2015). Bonds to the homeland: Patterns and determinants of women's transnational travel frequency among three immigrant groups in Germany. International Journal of Psychology 51(2), 130-138.

John, P., and Klaus F. (1994). Zimmermann. Blue collar labor vulnerability: Wage impacts of migration. The economic consequences of immigration to Germany. Physica-Verlag. 81-99.

Kunze, M. (2005). EU-Osterweiterung: Migration und Effekte auf dem deutschen Arbeitsmarkt. Mensch & Buch Verlag.

Mathias, A. (2013). Bringing Sociology to International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2(1), 7-17.

MFA of Kazakhstan. (2010). Mentality of the Peoples of the World. [Electronic recourse]. Assess mode: http://portal.mfa.kz/portal/page/portal/mfa/ru/content/policy/cooperation/Europe

Migrationbericht. (2014). [Electronic recourse]. Assess mode: www.bamf.de

Penny, H. G., & Rinke, S. (2015). Germans Abroad: Respatializing Historical Narrative. Geschichte und Gesellschaft, 41(2), 173-196.

Reißlandt, C. (2005). Von der" Gastarbeiter"-Anwerbung zum Zuwanderungsgesetz. Migrationsgeschehen und Zuwanderungspolitik in der Bundesrepublik. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Bonn.

Ryazantsev, S. V. (2015). The Modern Russian-Speaking Communities in the World: Formation, Assimilation and Adaptation in Host Societies. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 6(3 S4), 155.

Rys, Yu. (2008). Myths and reality of immigration to Germany. Journal of Social Sciences, 4(1), 342.

Santel, B. (2007). In der Realität angekommen: Die Bundesrepublik Deutschland als Einwanderungsland. Integration und Einwanderung. Schwalbach a. T., Wochenschau, 10-32.

Savoskul, M. S. (2006). Russian Germans: Germany’s image and integration into German society. Demoscope Weekly, No. 251-252. [Electronic recourse]. Assess mode: http://demoscope.ru/weekly/2006/0251/analit02.php

Seydakhmetova, B. (2016). The New Generation. . [Electronic recourse]. Assess mode: http://www.np.kz/index.php

Shabayev, Yu. P., Goncharov I. А., Sadokhin A. P. (2016). Life strategies of Russia's Germans. Sociological Studies. 1,100−107.

Stalker, P. (2002). Migration trends and migration policy in Europe. International Migration, 40(5), 151-179.

Tackle, M. (2007). German Policy on Imigration – from Ethnos to Demos?. Peter Lang. Frankfurt

Triadafilopoulos, T. (2015). Is multiculturalism dead? Groups, governments and the ‘real work of integration’. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 38(5), 663-680.

Winter, E. (2014). Traditions of Nationhood or Political Conjuncture?. Comparative Migration Studies, 2(1), 29-55.

1. Ardak Kapyshev. Abay Myrzakhmetov Kokshetau University, Republic of Kazakhstan