Vol. 38 (Nº 45) Año 2017. Pág. 22

Vol. 38 (Nº 45) Año 2017. Pág. 22

CANO, Jose A. 1; TABARES, Alexander 2

Recibido: 09/06/2017 • Aprobado: 25/06/2017

2. Determinants of Career Choice Intention

ABSTRACT: This article describes the determining factors of entrepreneurial intention in Colombia university students from GUESSS study data. The determinants of entrepreneurial intention are studied from the theory of planned behavior (TPB) through the variables of perceived desirability, perceived behavioral control and perceived social norms. Thus, the main personal motivations to be an entrepreneur, the strength of entrepreneurial intention, as well as the influence of family, and social context of university students are identified. |

RESUMEN: Este artículo analiza los determinantes de la intención emprendedora en estudiantes universitarios de Colombia a partir de los datos del estudio GUESSS. Los determinantes de la intención emprendedora se analizan desde la teoría del comportamiento planificado (TPB) a través de las variables de la deseabilidad percibida, el control del comportamiento percibido y las normas sociales percibidas. De esta forma, se identifican las principales motivaciones personales para ser emprendedor, la fuerza de la intención emprendedora, así como la influencia del contexto familiar y social en estudiantes universitarios |

Recently, an important amount of scholar studies has highlighted the importance of promoting entrepreneurship to stimulate economic development (Krueger, Reilly and Carsrud 2000; Wennekers, Van, Thurik and Reynolds, 2005; Shane 2009) and employment generation (Audretsch, 2002, Liñan and Rueda-Cantuche, 2011). Since entrepreneurship education has been considered one of the key instruments to increase the entrepreneurial attitudes of both potential and nascent entrepreneurs (Mitra, 2008; Potter, 2008), it is worth to determine the factors influencing entrepreneurial intention for the university students in order to promote them. As such, there is a need to examine antecedents for entrepreneurial intentions in more detail (Liñán and Chen 2009) and understand what makes students start their own firm (Markman, Balkin and Baron 2002; Zhao, Hills and Seibert, 2005).

One of the most distinguishing frameworks analyzing this phenomenon has been the theory of planned behavior (TPB) proposed by Ajzen (2002). This theoretical framework has particularly been helpful to analyze entrepreneurial intention and activity of students in several and relevant studies (Zellweger, Sieger and Halter, 2011; Bernhofer and Li, 2014; Bergmann, Hundt and Sternberg, 2016). However, few scholars have analyzed the determinants of university students’ entrepreneurial intentions in emerging economies (Lima, Lopes, Nassif, and Da Silva, 2015; Sieger and Monsen, 2015, Cano, Tabares and Alvarez, 2017) and much less using a wider set of career choices with varying degrees of entrepreneurial contents.

Thus, the study intends to fill this gap by describing the determining factors of university students’ entrepreneurial intention from the theory of planned behavior. This entrepreneurial intention is studied by two variables: one internal captured by the perceived desirability and the perceived behavioral control; one external captured by the perceived social norm. Consequently, we conduct an analysis of data generated in the Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ Survey (GUESSS), which considers a country sample of 801 students from 22 different universities in Colombia. The main results of this research suggest that the variables of internal determinants captured by the perceived desirability and the perceived behavior control as well as external factors captured by the perceived social norm affect the entrepreneurial intention and the activity of university students. Furthermore, the article provides comprehensive evidence about entrepreneurial intention factors in Colombia and thus it fills an important gap in the entrepreneurship literature by adding up insights from emerging economies to the debate. Then, the study advances the literature by providing new information on university students' entrepreneurial intention in Colombia. In addition, the paper offers practical implications for economic policy and for the public country representatives as well as the scientific community.

The article is structured as follows. After this brief introduction, in the second section, we introduce the theoretical framework of the theory of planned behavior and students’ entrepreneurial intention. The third section presents the details of the research methodology. The fourth section discusses the empirical results of the study. Finally, the study points out the most relevant conclusions and future lines of research.

Entrepreneurship or entrepreneurial behavior could be defined as the discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of an opportunity (Shane and Venkataraman 2000). However, this entrepreneurial behavior cannot be easily determined, since it is a phenomenon hard to observe and involves unpredictable time lags (Krueger and Brazeal, 1994). Thus, the theory of planned behavior proposed by Ajzen (1991) has emerged as a critical theoretical framework that explains the intentions are the most effective predictor of actual behavior and become a fundamental factor for explaining behavior not only in employment but also in academic intentions (Sieger and Modsen, 2015).

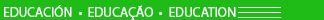

According to Ajzen (2002), human behavior is guided by behavioral, control and normative beliefs or perceptions. These three motivational factors that influence behavior could be classified into external and internal dimensions. As shown in Figure 1, the external dimension accounts for the perceived social norms, while internal dimension accounts for the perceived desirability and the perceived behavioral control.

Figure 1. Determinants of entrepreneurial intention and TPB

Source: Authors

With regard to the external construct, the perceived social norms take into consideration the perceived social and cultural pressure to carry out—or not to carry out—that entrepreneurial behavior. In other words, it refers to beliefs about normative expectations of reference groups such as parents, classmates, and friends. With regard to the internal construct, the perceived desirability is captured by the attitude towards the behavior, which reflects the degree to which the individual holds a positive or negative personal valuation about being an entrepreneur (Armitage and Conner, 2001). In turn, the perceived behavioral control is defined as the perception of the easiness or difficulty, called self-efficacy, and the control in the fulfilment of the behavior of interest, also called perceived controllability (Ajzen, 2002, Chen, Greene and Crick 1998; Mueller and Thomas 2001; Shapero and Sokol, 1982). Thus, and by comparing Shapero and Sokol’s variables (1982) with Ajzen’s ones (1991), it can be seen that the perceived social norms correspond quite well with the outer dimension and the perceived desirability as well as the perceived behavioral control correspond to the inner dimension of individuals. Hence, the determinants of university students’ entrepreneurial intentions can be studied on one side through a university, family and socio-cultural context. On the other side, these intentions can be studied through personal motivations, perceptions of self-efficacy and controllability.

As such, prior research has found that in terms of university, family and socio-cultural context, the literature suggests that the more positive subjective norms toward an entrepreneurial career are, the greater the likelihood that an individual will choose a specific career intention, whether be an employee, founder or successor (Schlaegel and Koenig 2014; Sieger and Modsen, 2015). In this line, Lima (2014) gives evidence that the university context, the design, content, and effects of entrepreneurship education represent a significant stream of research as well.

Similarly, other academic research studies have found confirmation on how the business experience of parents can influence on the intention to become entrepreneurs (Laspita, Breugst, Heblich and Patzelt, 2012). Respectively, both Ajzen (2002), Sieger and Monsen (2015) agree that the decision of entrepreneurs is also deeply rooted in the social life and cultural context in which individuals live. Therefore, social and cultural factors have an important effect on the formation of entrepreneurial intentions and they are addressed under the concept of perceived social norms or "subjective norms" in the theory of planned behavior (Azjen, 1991).

Respecting to the personal motivations, the more positive an individual’s attitude toward entrepreneurship, the greater the likelihood that he or she will choose (Schlaegel and Koenig 2014: Sieger and Modsen, 2015). Similarly, in terms of self-efficacy and controllability, scholars state that individuals, who are very confident of their entrepreneurial skills and capabilities and feel a certain degree of control, will be more likely to form entrepreneurial intentions (McGee, Peterson, Mueller and Sequeira, 2009; Mueller and Thomas 2001; Shapero and Sokol 1982; Sieger and Modsen 2015; Zhao, Hills and Seibert 2005).

The study follows a descriptive analysis on the determining factors of university students' entrepreneurial intentions from data generated in the Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ Survey (GUESSS), an international research project that adopts and tests the Theory of Plan Behavior Model. At GUESSS Colombia, a team of faculty members applied an online survey instrument in English provided by the UGC-HSG Institute of the University of St. Gallen (Switzerland). The questionnaire contains 16 sets of multiple-choice questions employing scales of five and seven points and it examines different aspects such as basic student information, education level, career choice intentions (founder successor, employee, and reasons for career choice, among others). Under the leadership of Universidad de Medellin, the survey is conducted in six universities, providing a final sample size of 801 students.

In order to achieve validity and reliability, the survey examines all the motivational determinant factors that influence behavior in terms of two internal dimension aspects such as perceived desirability and perceived behavioral control captured by personal motivations, perceptions of self-efficacy and controllability and one external dimension aspect such as the perceived social norms captured by the fellow students, parents and friends’ expectations.

In order to identify the inner dimension in terms of personal motivation, the strength of the students’ entrepreneurial intention is considered and then some comparisons with the results of global GUESSS conducted by Sieger, Fueglistaller, and Zellweger (2014) are made. On this point, it is conducted a deeper analysis by comparing the entrepreneurial intention with the help of two variables such as the fields of study and the gender. Regarding the inner dimension of perceived self-efficacy and controllability, it is studied the perception of risk when creating an own business and later it is made some comparisons with the international report. With the aim of identifying the social norm outer dimension, the university, family, and socio-cultural contexts are examined and then a contrastive analysis with the 2013-2014 global GUESSS report is done.

Since this dimension offers several and critical insights, the personal motivations, perceptions of self-efficacy and controllability are characterized.

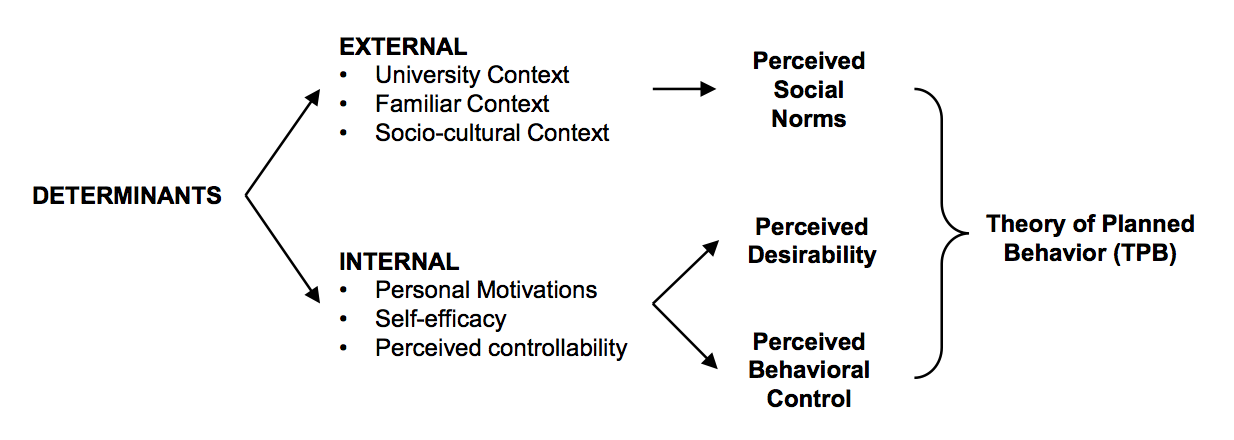

Concerning the perceived desirability, which reflects the degree to which the individual holds a positive or negative personal valuation about being an entrepreneur (Ajzen, 2002), and the perceived behavioral control, which reflects the confidence and the control in the fulfilment of the entrepreneurial intention, Figure 2 shows and assesses 10 personal motivations and perceptions of self-efficacy and controllability to be an entrepreneur on a scale from 1 to 7 (1 = not important, 7 = very important).

Figure 2. Personal motivations and perceptions of self-efficacy and controllability to be an entrepreneur

The study suggests that the most influencing personal motivation in the intention of being an entrepreneur is "to make your dream true", while the most influencing perceived self-efficacy factor is "to take advantage of your creative needs" and "to create something”. Respecting to the perceived controllability the highest factor is "to have the power to make decisions" (a concept of autonomy and independence). In this regard, other two items, considered as important controllability factors indicate that students are encouraged by having control and authority being their own boss. The motivations with the lowest valuation are two: "to have an exciting job" and "to have a challenging job".

By comparing the current study analysis with the international report GUESSS 2013-2014 (Sieger et al., 2014), it is evident that making one’s dream true is the most important motivation, not only in Colombia but also in countries such as Mexico, Romania, Brazil, Argentina, and Slovenia. Contrary to this trend, countries such as France, Japan and Germany show low scores to this motivation. Thus, it seems that the motivation to make a dream true through entrepreneurship is related to developing economies, and it is less valued in developed economies.

Since the results of the study show that the force of entrepreneurial intention in Colombia is higher compared to the world average, it is necessary to make a deeper analysis of this issue with the help of two variables such as the fields of study and the gender.

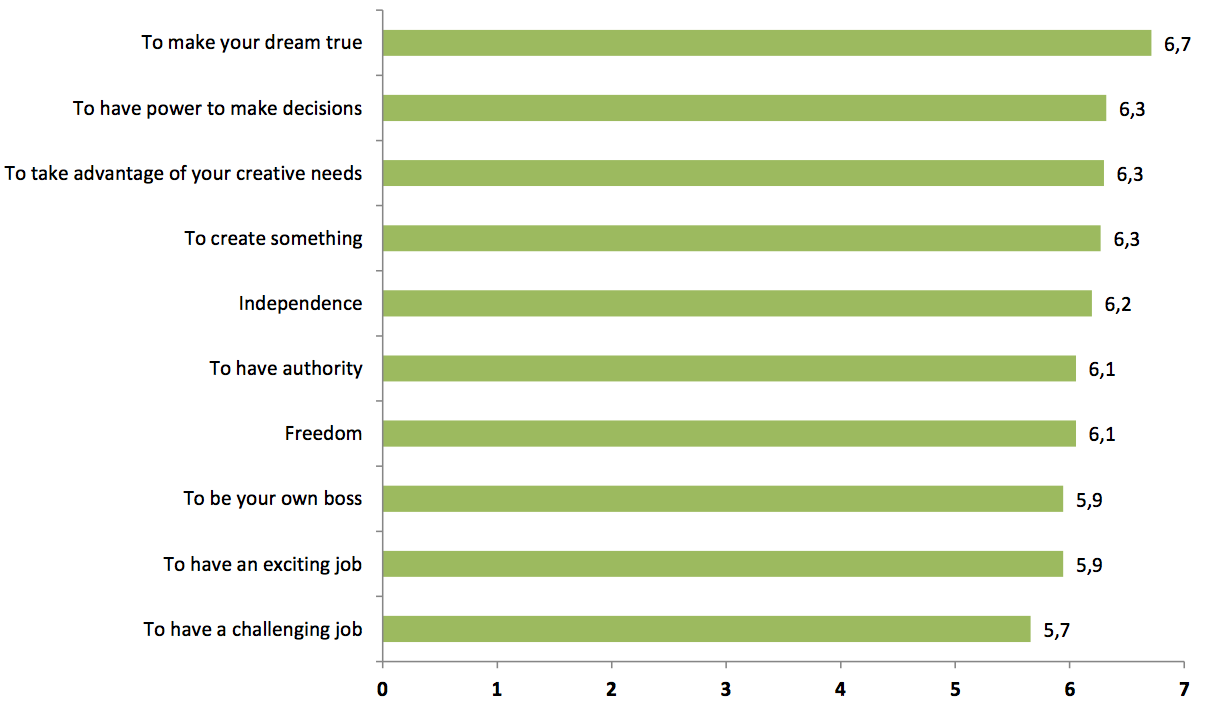

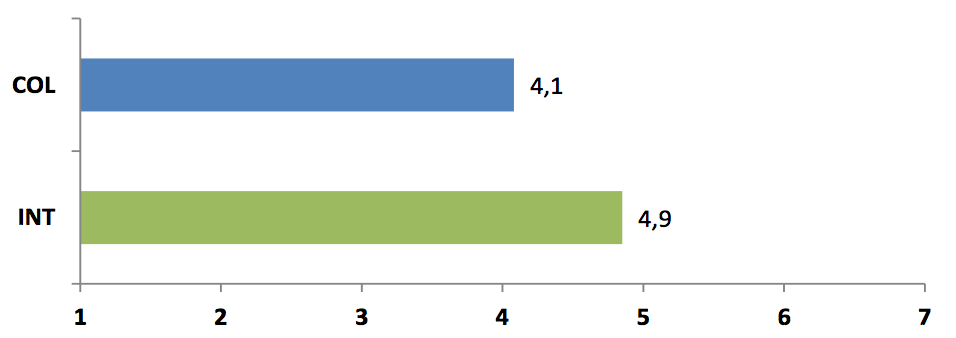

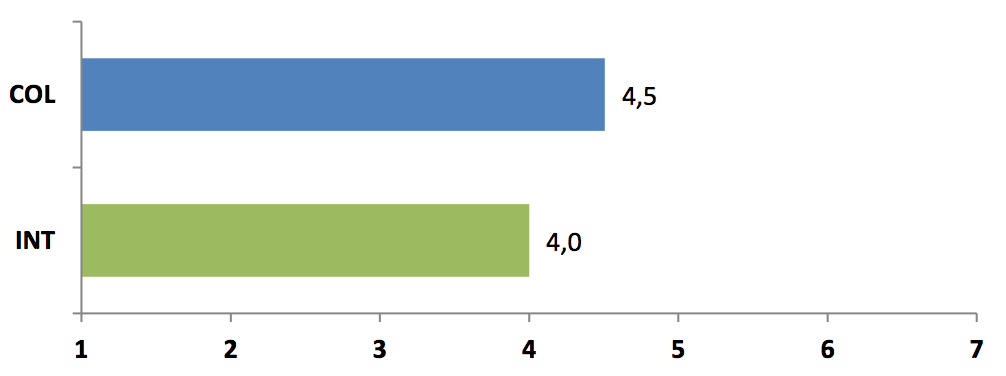

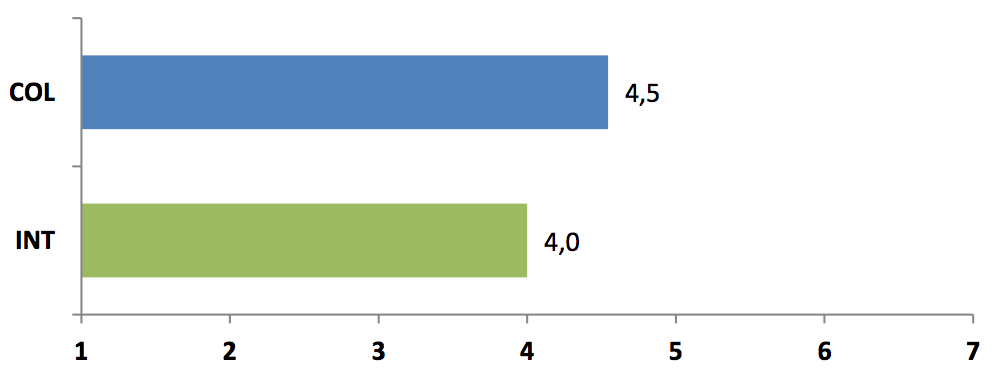

The strength of entrepreneurial intention is measured by six (6) indicators, which are rated by students on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). These indicators correspond to the students’ intention, decision and determination to create and manage their own business. Thus, Figure 3 identifies that university students in Colombia (COL) have a strong entrepreneurial intention, with a value of 1.5 above the international report (INT), a study made by Sieger, Fueglistaller, and Zellweger (2014).

Figure 3. Strength of entrepreneurial intention – Colombia vs International

According to these data of the GUESSS project international report (2013 /2014), Colombia is the second country with greater strength of entrepreneurial intention after Mexico, with a similar average to several developing economies such as Argentina, Malaysia, and Russia (Sieger, Fueglistaller and Zellweger, 2014). An opposite pattern is given in developed economies such as France, Netherlands, Austria, Switzerland, Germany, and Japan, which are below the world´s average with a value of 3,7. These data suggest that the strength of the entrepreneurial intention of students is inversely proportional to the development of their countries.

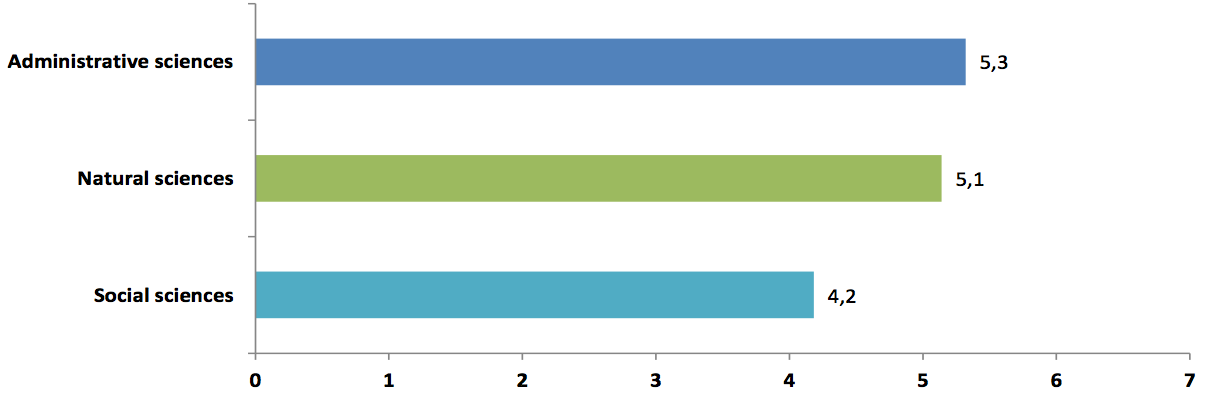

Figure 4 details the results of the strength of entrepreneurial intention by fields of study, indicating an average value of 5,3 in administrative sciences students, slightly above the students average in the natural sciences (5,1). Unlike this trend, students from social sciences have an average of 4,2, even though it seems lower than the first two other fields in Colombia, it is higher than the international value which is 3,7.

Figure 4. Strength of entrepreneurial intention by fields of study

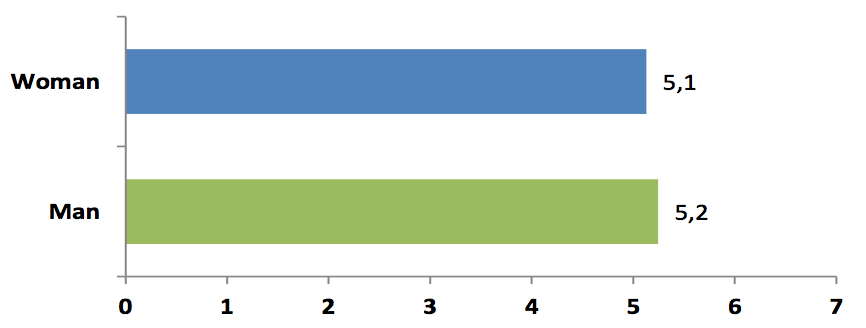

As shown in Figure 5, the strength of entrepreneurial intention force by gender points out that there are no significant differences in the strength of entrepreneurial intention among men and women.

Figure 5. Strength of entrepreneurial intention by gender

Therefore, the results of the strength of entrepreneurial intention in Colombia is consistent with the career intention to be a founder. Regarding this, the national average is above the world’s average and there is no significant difference by gender. The study fields both administrative and natural sciences show remarkable averages in this topic.

With the aim to understanding better the other two inner dimension of perceived self-efficacy and controllability, it is also considered the perception of risk when creating an own business. In order to assess them, students are asked to indicate their agreement or disagreement (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) about considering risky to start a business, managing their own business and being the owner of a business. As shown in Figure 6, the perception of risk for university students in Colombia is 0.9 points below the world’s average, which means that Colombian students are less afraid to make the decision to be an entrepreneur. According to the results, the study suggests that local institutions should focus more on tasks to reduce the perception of risk of starting a business.

Figure 6. Risk perception – Colombia vs International

Similarly, in the international report (Sieger et al., 2014), it is found that developed economies such as Japan, United States, Denmark, and Germany perceive the fact to be an entrepreneur as a high risk with values above 5,0, meanwhile in Latin American countries such as Argentina, Colombia, Mexico and Brazil the perception shows the lowest risk levels.

Since this dimension offers several and critical insights, the university, the family, and the socio-cultural contexts are considered independently.

Regarding the university context of the students, it is clear from Figure 7 that only 7% of students are studying in a program dedicated specifically to entrepreneurship, while 46% of respondents say they have attended a course on entrepreneurship. Moreover, about one in five students have attended at least one course in entrepreneurship as a compulsory part of the studies, while two out of five students have attended an elective course in entrepreneurship. In this point, it is necessary to clarify that the sum of values on Figure 7 does not reach 100% because students can choose one or more answers.

Figure 7. University context

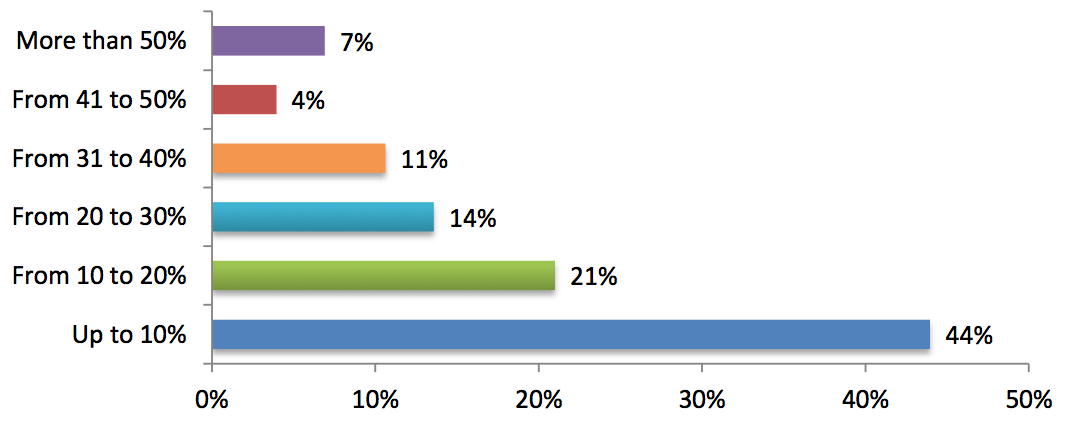

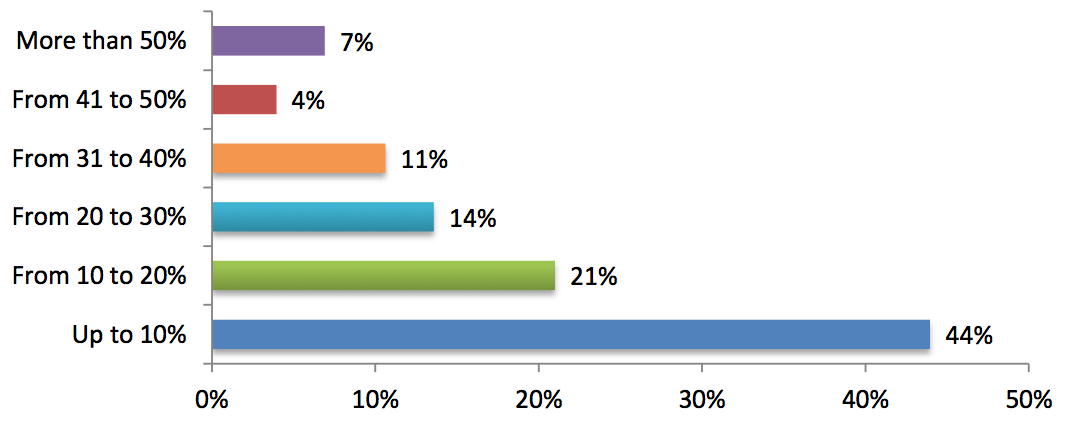

Similarly, Figure 8 presents the percentage of total study time that students devote in their entrepreneurship courses. As such, 44% of students have devoted 10% or less of their study time to entrepreneurship courses. If the first two percentages are added up (students who have devoted up to 20% of their time to entrepreneurship courses), it is concluded that a high percentage of students (65%) has not had a recurring or important training in entrepreneurship.

Figure 8. Percentage of time devoted to entrepreneurship courses

Given the results of this study in Colombia and with reference to some of the conclusions of Lima Lopes, Nassif and Silva (2011), universities should offer more courses and mentoring programs for entrepreneurs, workshops and collaborative work with experienced entrepreneurs and potential investors, and also provide financing for business creation.

Otherwise, with the aim of measuring the effectiveness of education in entrepreneurship in Colombian universities, Figure 9 shows the contribution that courses and training in entrepreneurship have generated in university students. This contribution is related to attitudes, values, and motivations of entrepreneurs, skills and actions to start a business, developing networks and identifying opportunities.

Figure 9. Assessment of entrepreneurial learning process in universities

The average value obtained reveals a slightly positive assessment of entrepreneurship learning in the country's universities. If these values are compared to the international exhibition there is evidence once again that Colombia is characterized by a better perception about entrepreneurship, specifically in the university context. According to Sieger et al. (2014), these results require more research on how the university context enables the creation of enterprises that in turn could generate significant impacts on social and economic aspects.

To delve into this results, Figure 10 shows the entrepreneurial environment provided in different universities in Colombia. It is measured on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) as to whether the college environment inspires to develop ideas for new businesses, helps to become entrepreneurial and motivates to engage in entrepreneurial activities (Luethje and Franke, 2004).

Figure 10. University environment – Colombia vs International

The results show a slightly positive assessment of the entrepreneurial environment in Colombian universities, which even is 0.5 points above the world’s average. Therefore, Colombia owns a better perception of an entrepreneurial environment at universities regarding the international sample. This fact is reflected in a stronger entrepreneurial intention and a higher motivation for attending entrepreneurship elective courses, as noted respectively in Figure 3 and Figure 7.

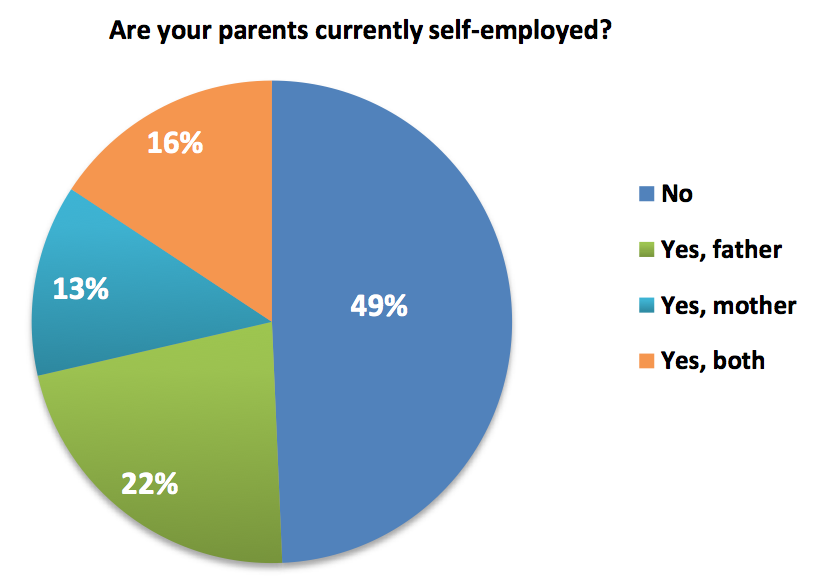

Figure 11 provides a perspective of the family context surrounding university students that could influence their career intentions, showing the percentage of students with self-employed parents.

Figure 11. University students and self-employed parents

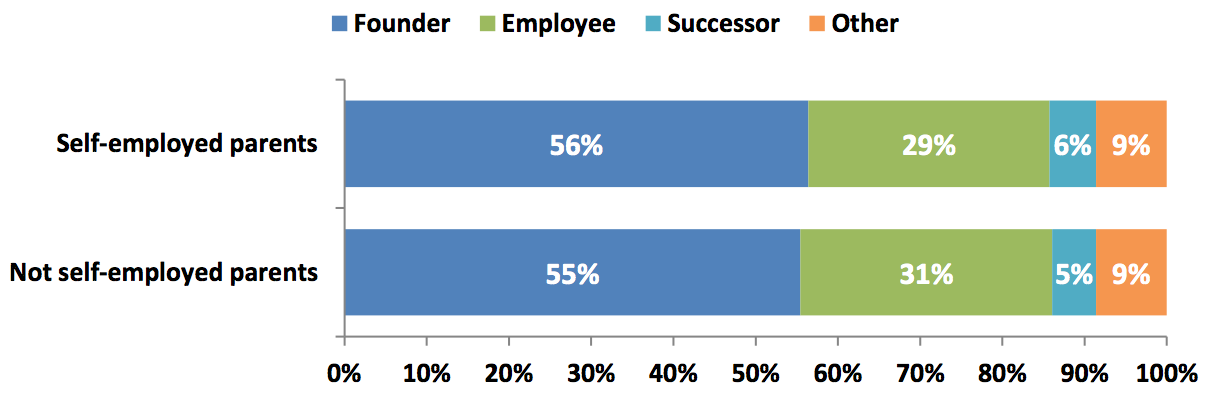

About half of the students surveyed (51%) indicates that at least one of their parents is self-employed and has their own business, noting that there are more male self-employed parents than female self-employed parents. These results highlight a significant percentage of students with an entrepreneurial family environment, which can be very conducive to potentiate the entrepreneurship. For a better understanding, Figure 12 shows a comparison between the career intentions in a long-term of students who have entrepreneurial parents and students whose parents are not entrepreneurs.

Figure 12. Self-employed Vs not self-employed parents and career intentions

The intention to create a business in both cases is almost identical because self-employed-parents’ students’ intention to be founders represents only one percentage point above those not-self-employed parents’ students. Regarding the intention of being a successor, the situation is similar, so the study suggests that self-employed parents do not necessarily influence the students’ decision to be founders or successors of their parents’ business. These results differ from the international report, which notes a difference of 11% in favor of students who want to create a business even having self-employed parents (Sieger, Fueglistaller and Zellweger, 2014).

Regarding the social and cultural context, the study explores how close relatives, classmates, and friends would react if university students follow a career as an entrepreneur. The responses are determined from 1 (very negative) and 7 (very positive). This scale allows obtaining the results of Figure 13.

Figure 13. Social norms – Colombia vs International

The perception of how social groups react regarding the choice of career as an entrepreneur in Colombia has a relatively high rating (5,9) and a median of 6,3. Particularly, immediate family is the predominant social norm for entrepreneurial students in Colombia, followed by friends and their classmates, reflecting the importance of the opinion of closest people about entrepreneurship. The results in Colombia exceeds the world’s average, being ranked worldwide on the third place after Mexico and Brazil (Sieger et al., 2014): this latter fact reflects that social norms in Colombia are positive to entrepreneurship. Otherwise, in industrialized countries or developed economies such as Netherlands, Australia, Denmark, Germany and Japan, the values of social norms about entrepreneurship are below the world´s average and it confirms once again that the entrepreneurial intention of students is inversely proportional to the development of their countries.

The research identifies that the personal motivations that influence the choice of being an entrepreneur in Colombia are related to make a dream true, have the power to make decisions, take advantage of their creative needs, and create something. This means that entrepreneurship represents a lifestyle and gives them independence in terms of decision-making, and grants them to exploit their talents and skills as to create new products and services. Likewise, in Colombia, the strength of entrepreneurial intention in university students is considered of great magnitude and it outperforms the global average. Moreover, this entrepreneurial intention stands out values for the fields of study in administrative sciences and natural sciences and it shows similar values between men and women.

Regarding the university context, the study states that Colombian students have training options in entrepreneurship, either through elective or compulsory courses in their curriculum. However, the students say that they usually spend a low percentage of the total study time. It is also found that entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial environment offered by universities in Colombia has a greater impact than the world’s average. Therefore, the study suggests that the country needs to improve the effectiveness of the entrepreneurship education and generate projects that provide significant impacts on the social and economic level.

On the other hand, the family environment is not decisive for the intentions of being an entrepreneur. Similar behavior is evident in the intention to be a successor, despite the fact that more than half of students have one or both self-employed parents. These results encourage more scholar research on reasons why there are no changes in career intention for these students. Comparing the current study with the international report GUESSS 2013/2014, Colombian students have a lower risk perception about being an entrepreneur, and the social groups surrounding students support the idea that a student can become an entrepreneur.

The GUESSS Colombia 2013/2014 study confirms the trend that the strength of the entrepreneurial intention of students is inversely proportional to the development of their countries. In addition to this, it states that the perception of social groups to the decision to be an entrepreneur is more positive in developing economies than in developed economies, while the risk perception of being an entrepreneur increases in developed economies and decreases in developing economies.

AJZEN, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(1), 665-683.

AJZEN, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179-211.

ARMITAGE, C.J., & CONNER, M., (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behavior: a meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 471–499.

BERNHOFER, L.B., & LI, J. (2014). Understanding the entrepreneurial intention of Chinese students: The preliminary findings of the china project of Global university entrepreneurial spirits students survey (GUESSS). Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 6(1), 21-37.

BERGMANN, H., HUNDT, C., & STERNBERG, R. (2016). What makes student entrepreneurs? On the relevance (and irrelevance) of the university and the regional context for student start-ups. Small Business Economics, 47(1), 53-76.

CANO, J. A., TABARES, A., & ALVAREZ, C. (2017). University students’ career choice intentions: GUESSS Colombia study. Revista Espacios, 38(5), p. 20. Retrieved from: http://www.revistaespacios.com/a17v38n05/17380520.html

CHEN, C.C., GREENE, P.G., & CRICK, A. (1998). Does Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy Distinguish Entrepreneurs from Managers?. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316.

KRUEGER, N.F., & BRAZEAL, D.V. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 19(3), 91-104.

KRUEGER, N., REILLY, M.D., & CARSRUD, A.L. (2000). Competing Models of Entrepreneurial Intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432.

LASPITA, S., BREUGST, N., HEBLICH, S., & PATZELT, H. (2012). Intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(1), 414–435.

LIMA, E., LOPES, R.M., NASSIF, V., & SILVA, D. (2011). Intenções e Atividades Empreendedoras dos Estudantes Universitários: Relatório do Estudo GUESSS Brasil 2011. São Paulo: UNINOVE.

LIMA, E., NASSIF, V.M., LOPES, R.M., & SILVA, D. (2014). Educação Superior em Empreendedorismo e Intenções Empreendedoras dos Estudantes: Relatório do Estudo GUESSS Brasil 2013-2014. São Paulo: Grupo APOE.

LIMA, E., LOPES, R.M., NASSIF, V., & DA SILVA, D. (2015). Opportunities to improve entrepreneurship education: Contributions considering Brazilian challenges. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(4), 1033-1051.

LIÑÁN, F., & CHEN, Y.W. (2009). Development and Cross-Cultural Application of a Specific Instrument to Measure Entrepreneurial Intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617.

LIÑÁN, F., RODRÍGUEZ-COHARD, J.C., & RUEDA-CANTUCHE, J.M. (2011). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 195-218.

LUETHJE, C., & FRANKE, N. (2004). Entrepreneurial intentions of business students: a benchmarking study. International Journal of Innovation and Technology, 1(3), 269-288.

MARKMAN, G.D., BALKIN, D.B., & BARON, R.A. (2002). Inventors and New Venture Formation: The Effects of General Self-Efficacy and Regretful Thinking. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 149.

MCGEE, J.E., PETERSON, M., MUELLER, S.L., & SEQUEIRA, J.M. (2009). Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy: Refining the Measure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33(4), 965–988.

MITRA, J. (2008). Towards an analytical framework for policy development. In J. Potter (Ed.), Entrepreneurship and higher education. Paris: OECD—Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED).

MUELLER, S.L., & THOMAS, A.S. (2001). Culture and Entrepreneurial Potential: A Nine Country Study of Locus of Control and Innovativeness. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(1), 51–75.

POTTER, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship and higher education. Paris: OECD—Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED).

SHANE, S. (2009). Why Encouraging More People to Become Entrepreneurs Is Bad Public Policy, Small Business Economics, 33(2), 141–149.

SHANE, S., & VENKATARAMAN, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217-226.

SHAPERO, A., & SOKOL, L. (1982). The Social Dimensions of Entrepreneurship, in The Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurship. Eds. C. A. Kent, D. L. Sexton, and K. E. Vesper. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall, 72–90.

SCHLAEGEL, C., & KOENIG, M. (2014). Determinants of Entrepreneurial Intent: A Meta-Analytic Test and Integration of Competing Models, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291–332.

SIEGER, P., FUEGLISTALLER, U., & ZELLWEGER, T. (2014). Student Entrepreneurship Across the Globe: A Look at Intentions and Activities. St.Gallen: Swiss Research Institute of Small Business and Entrepreneurship at the University of St.Gallen.

SIEGER, P., & MONSEN, E. (2015). Founder, academic, or employee? A nuanced study of career choice intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(S1), 30-57.

WENNEKERS, S., VAN STEL, A., THURIK, R., & REYNOLDS, P. (2005). Nascent Entrepreneurship and the Level of Economic Development. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 293–309.

ZELLWEGER, T., SIEGER, P., & HALTER, F. (2011). Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(5), 521-536.

ZHAO, H., HILLS, G.E., & SEIBERT, S.E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265-1272.

1. Universidad de Medellín. Ingeniero Industrial, Magister en Ingeniería Administrativa. jacano@udem.edu.co

2. Universidad de Medellín. Profesional en Idiomas, Magister en Administración, Estudiante de Doctorado en Administración. atabares@udem.edu.co