Vol. 38 (Nº 22) Año 2017. Pág. 17

Tuany K. C. ASSIS 1; Maria H. ALVES 2

Recibido: 17/11/16 • Aprobado: 15/12/2016

ABSTRACT: The aim of the study is to present a checklist of the marine macroalgae that occur at two beaches, Atalaia and Carnaubinha, located in Luis Correia, in the coast of Piauí. The samplings were collected during excursions in the period from October 2014 to April 2015, according to the usual methodology in phycology. A total of 48 taxa were obtained mostly from Carnaubinha beach (45spp), which shows great diversity. In this study we added three species of macroalgae, which increases from 108 to 111 the number of taxa in the coast of Piauí. Based on the results it may be stated that they are significant and represent a fresh impetus for insights into other fields of studies with the use of macroalgae. We emphasized that this is the first taxonomyc study at Atalaia and Carnaubinha beaches, in Luis Correia, Piauí. |

RESUMO: Neste estudo apresenta-se uma lista dos táxons de macroalgas marinhas ocorrentes em duas praias, Atalaia e Carnaubinha, do litoral do Piauí, áreas ainda pouco exploradas, no que se refere ao conhecimento ficológico e também propicias a ações de preservação. O material ficológico foi coletado durante excursões, no período de Outubro de 2014 a Abril de 2015, segundo metodologia usual em Ficologia e posteriormente analisado e identificado. Foram obtidos 48 táxons, sendo sua maioria da praia de Carnaubinha (45spp.), a qual demonstra grande diversidade. Nesse estudo foram acrescidas três táxons de macroalgas o que eleva de 108 para 111 o número de táxons no litoral piauiense. Diante dos resultados pode-se afirmar que estes são significativos e representam novos impulsos para aprofundamentos de outros campos de estudos com a utilização das macroalgas. Este e o primeiro estudo taxonômico para as praias de Atalaia e Carnaubinha, Luis Correia, Piauí. |

One of the environments that houses great diversity of living beings is the coastal ecosystem in which the biota associated with consolidated and unconsolidated substrates, also known as benthos, is highly diverse and complex, including important organisms in biogeochemical cycles of the seas and oceans (Amaral & Migotto, 2011).

Among the coastal benthic components, marine macroalgae communities play an important ecological role in maintaining marine ecosystems, similar to that of terrestrial plants. The marine macroalgae act to provide oxygen, food and to serve as nursery for several agencies of different trophic levels of the food chain (Dawes, 1986).

Knowledge and preservation of physiological diversity become indispensable because the algae not only act on the stability of natural ecosystems but are also used in other dimensions such as the resettlement of aquatic ecosystems, applications in bioremediation processes and analytical chemistry, as well as the industrial use (Vidotti & Rollemberg, 2004).

Wynne (2011) designated the marine benthic algae in three phyla: Chlorophyta, Heteronkontophyta (Phaeophyta) and Rhodophyta, which usually have simple morphological organization and great physiological complexity (Yoneshigue-Valentin et al., 2006) and are abundant in the area between tides and infralittoral environments, in addition to being found on some type of fixed substrate (Almeida, 2013).

In recent decades, aquatic ecosystems have been changed to take account of multiple environmental impacts resulted from human activities (Goulart & Callisto, 2003), mainly through pollution (release of industrial and household waste), introduction of exotic species and growing occupation of natural landscapes. In coastal areas, these factors may cause risk to biodiversity through changes in the associated communities of algae and fauna, which are sensitive to changes introduced by men (Ortega, 2000).

Piauí coastal zone covers an area of 66 km, entirely located in the Environmental Protection Area of the Delta of the Parnaíba and presents characteristic flora of tropical regions (Horta et al., 2001). It is characterized by the presence of a diversity of ecosystems that participate and contribute to the coastal balance and dynamics, including: deltas, estuaries, lagoons, sand bars, some cliffs, dunes, the coastal vegetation itself, mangroves and reefs (Baptista, 2004; Santos Filho, 2009).

Oliveira et al. (1999) cataloged nine species of macroalgae in Piauí while studying the coast of Brazil. However, research that contribute significantly to the knowledge of the biodiversity of this phycoflora have been published in the last two decades, such as the works of Copertino & May (2010), Batista (2011), Alves & Carvalho (2012), Voltolini et al. (2012) and Santos Filho et al. (2012).

Studies carried out in Piauí are still in their initial phase, thereby emphasizing the need for further study of the diversity already diagnosed but not fully known, since they are extremely important places with respect to preservation. At strategic and unexplored areas, such as the coast of Piauí, conducting inventories is required to provide not only information about the distribution limits of various kinds, but also references to conservation purposes.

The aim of this study was a taxa inventory of the marine macroalgae that occur at Atalaia and Carnaubinha beaches, in Luis Correia, Piauí, as they are unexplored areas and also because almost nothing is known about the diversity of macroalgae.

The sampling was collected at Atalaia (2o 86' 83", 41o 64' 91") and Carnaubinha (2o 90' 68", 41o 50' 12") beaches in the municipality of Luis Correia (Figure 1), Piauí, Brazil, which is about 338km away from the state capital, Teresina. According to the Koppen classification the climate is tropical warm (Aw), with an average temperature of 27.5°C, average annual rainfall of 1,200 mm, and the wettest quarter comprises the months of February, March and April (Aguiar, 2004).

Figure 1: Location of the Atalaia and Carnaubinha beaches, City of Luis Correia, Piauí State.

Fonte: https://www.google.com.br (modified).

Atalaia beach is characterized as dissipative with low energy waves and fine sand grain size, and is associated with the mouth of the Parnaíba river (Batista, 2011). As for Carnaubinha beach, it presents well-marked bays and is characterized by the presence of sandstone reefs that come to surface at low tide of the mesolittoral, and are composed by sediment of quartz sand grains, calcareous shells, calcified animal skeletons and decomposed rocks (Baptista 2004).

The phycological material was collected during excursions in each beach, a total of eight, from October 2014 to April 2015. The samples were collected in the intertidal zone during the low tide period, removing the macroalgae out of the rocky outcrops with the aid of stilettos. At Atalaia beach, samples were taken from the rocks in the so-called "breakwater", a place adjacent to the Port of Luis Correia. Later, they were stored in glass or dark bags with Transeau and/or 4% formalin solution, properly labeled and preserved according to Cordeiro-Marino et al. (1984).

In the Laboratory of Botany at the Federal University of Piauí, Ministro Reis VellosoCampus, UFPI/CMRV, the algae were studied considering the morphology and the study of histological sections by using a stereoscopic microscope (magnifying glass) and an optical microscope.

In order to identify the specific level we adopted the works of Oliveira-Filho (1977), Joly (1965), a comparison with algae works in the area, such as Copertino & May (2010), Batista (2011), Carvalho & Alves (2011), Alves & Carvalho (2012), and another one presented in a congress, Assis et al. (2014), as well as dichotomous specific publication keys. The taxonomic classification system was proposed by Wynne (2011). The dried specimens were incorporated into the Herbarium of the Delta of the Parnaíba/HDELTA.

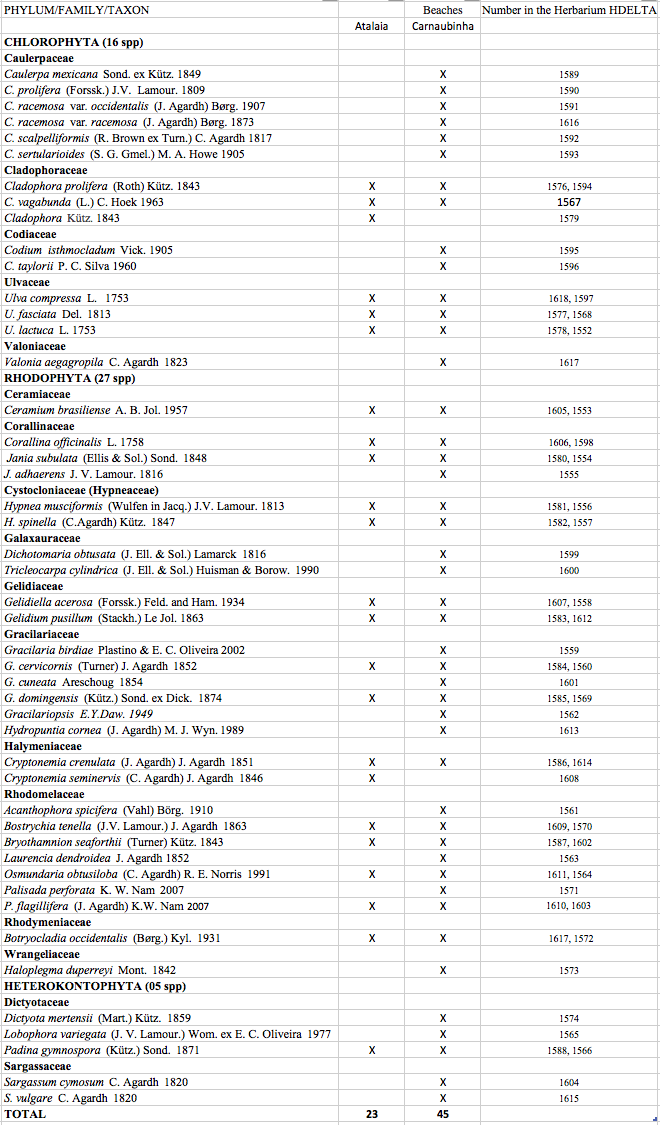

As a result of the analysis with samples of algae from Atalaia and Carnaubinha beaches, 48 taxa were obtained: 16 Chlorophyta, 27 Rhodophyta and cinco Heterokontophyta, distributed in 17 families (Table 1). A larger number of taxa was found at Carnaubinha beach (45 spp.), and 20 taxa were common to both sampling sites. The Rhodophyta showed the highest amount of taxa (27spp.) distributed in 10 families and the most representative was Rhodomelaceae (7 spp), followed by Gracilariaceae (6 spp). The Division with fewer species was Heterokontophyta with two registered families: Dictyotaceae (3 spp) and Sargassaceae (2 spp.).

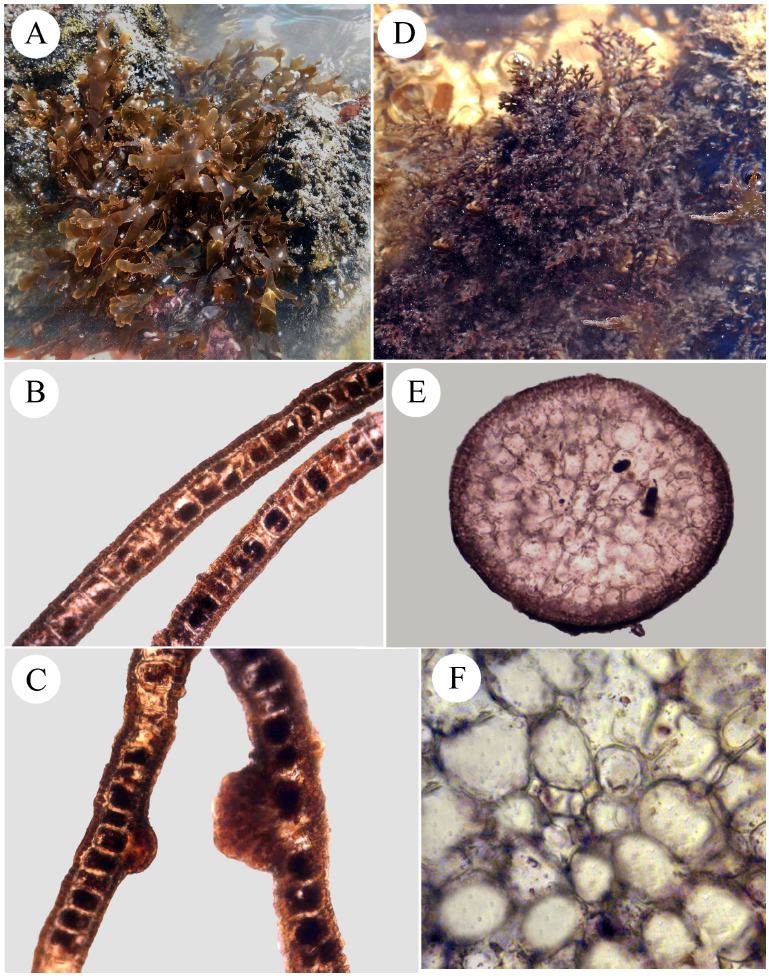

There was the increase of two taxa: Palisada flagillifera (J. Agardh) K.W. Nam. and Dictyota mertensii (Martius) Kütz. (Figure 2) for Coastal algae listing of the coast of Piauí. In addition to these taxa, Cladophora sp. and Gracilariopsis sp. were also identified.

Carnaubinha beach had the highest number of taxa (45) and this is mainly due to the location physiognomy, with sandstone reefs. Places protected from the breaking of waves, such as sandstone reefs, favor the establishment and development of a high number of species, not only of marine flora but also fauna, and such diversity of reef ecosystems is considered as high as the one existing in tropical forests (Correia, 2005).

Supporting this work is an emphasis on the statement made by Voltolini et al. (2012) on the fact that the diversity of macroalgae is especially related to the environmental conditions that are favorable to the type of substrate available for the attachment of spores and water quality.

Table 1: List of taxa recorded at Atalaia and Carnaubinha beaches, Luis Correia,

Piauí, October 2014 to April 2015. Legend: x = presence of taxon.

On the other hand, Atalaia Beach is characterized by being associated with the mouth of the Igaraçu river, east arm of the Parnaíba river that belongs to the Delta of the Parnaíba, in the Atlantic Ocean near the city of Luis Correia. It is common in such settings that pollutants released from residences and industries are transported through the course of the rivers along the coast, therefore contributing to the reduction of marine biodiversity (Oliveira et al., 2005). Another relevant factor is the intense herbivory existing in this habitat, mainly by sea turtles, as the Piauí coast is an important spawn area of five species of turtles (Santana et al., 2009).

The increase in herbivory intensity changes the macroalgae community, with leafy macroalgae replaced by clumps and filaments of rapid successional growth by other forms of calcareous [Corallina officinalis L., Jania subulata (Ellis & Sol.) Sond.] and foliaceous algae [Cladophora prolifera (Roth) Kütz., Gracilaria cervicornis (Turner) J. Agardh, Cryptonemia crenulata (J. Agardh)J. Agardh and Cryptonemia seminervis (C. Agardh) J. Agardh] (Batista, 2011), observed at Atalaia beach.

The representativity of red algae studied in this research, supports the claims of Bicudo and Menezes (2010), who argue that the Rhodophyceae is the one that presents the greatest diversity in the coast of Brazil (1,666 taxa), as it represents the class of marine benthic macroalgae with the highest number of species, approximately 4,000 (Lee, 2008).

Green algae (16 spp.) correspond to those found in the works of Copertino & May (2010), who studied eight taxa, and Batista (2011), who found 21; however, the authors did not refer to the locations at the beaches where the taxa were collected. On the other hand, Alves & Carvalho (2012) studied the green macroalgae of Coqueiro da Praia and Barra Grande (Luis Correia) and Cajueiro da Praia (Cajueiro da Praia) cataloging 23 taxa, among which 16 taxa of Atalaia and Carnaubinha are inserted.

The highlight genus was Caulerpa, with six taxa, whose growth occurs through stolons and vegetative reproduction by fragmentation, which enable the genus with a large substrate capacity for colonization, leading consequently to high representativity of Bryopsidales in most floristic studies (Barata, 2008; Almeida, 2013).

Regarding the brown algae, five taxa were studied. This little occurrence of brown algae may be related to environmental factors present in the habitats investigated, such as temperature, salinity and luminosity, which directly interfere in the life cycles of those algae (Jaenicke, 1977; Teixeira et al., 1987 cited in Baptista, 2011), because above all, they belong to a division with very peculiar characteristics of proliferation.

Although the number of taxa of brown algae found in this study has not been significant, they can act as excellent substrates for fixing other macroalgae, favoring the epiphytism. Thus, Santos Filho et al. (2012) cataloged 18 taxa of epiphytic macroalgae at Coqueiro Beach (Luis Correia) while studying Sargassaceae (Sargassum). Supporting the findings of this study we may highlight: Hypnea musciformis (Wulfen) Lamour., H. spinella (C. Agardh) Kütz. and Cladophora proliferates (Roth) Kütz.

In general the wide variety of macroalgae collected is attributed to the geographical positioning of the state of Piauí, as it is the northeastern coast of the country, which is one of the most diverse areas in terms of marine flora that mainly occur due to the elements of hot and oligotrophic waters associated with favorable substrates (Horta et al., 2001; Santos & Moura 2011).

The number of found taxa was relevant and this number (48) along with the macroalgae from other studies in Piauí, such as Batista (2000), Copertino & May (2010), Batista (2011), Carvalho & Alves (2011), Alves & Carvalho (2012), Voltolini et al. (2012), Santos Filho et al. (2012) and Assis et al. (2014) rises from 108 to 111 the number of taxa in Piauí, a very significant number if compared to nine taxa recorded until 1999, as Oliveira and colleagues cited. It is also noteworthy that the methodology used for the collection was random.

Considering the diversity as well as the aggregated ecological character of these organisms, we suggest further studies to be carried out so that the macroalgae may be further explored in terms of knowledge and may be properly preserved in its natural environment.

Figure 2:

Dictyota mertensii. (A) Habit. (E) Detail of the cell. 10x. Cell 60µ. (F) Detail of the estruture reproductive – 40x.

Palisada flagillifera (D) Habit. (B) cross section 4x. (C) Detail 10x, cortical cell 30µ.

Based on the results it can be said that they are meaningful because in addition to confirming the work already developed in the area, it presents new impulses for insights, not only in this field of study, but in many others that depend on such prior knowledge about the biodiversity of the phycoflora belonging to the coast of Piauí. Moreover, the data demonstrate a great diversity at Carnaubinha beach, which had not been explored, representing directions for preservation actions of this environment that is considered unchanged.

Institutional Scholarship Program for Scientific Initiation, PIBIC/UFPI for the financial support fellowship; and the Federal University of Piauí - UFPI, for the transportation given for the collection of phycological material, which made the realization of this research possible.

Aguiar, R.B. (2004). Projeto cadastro de fontes de abastecimento por água subterrânea, Estado do Piauí: Diagnóstico do município de Luís Correia. Aguiar, R. B. and Gomes, J.R.C. (Org). Fortaleza: CPRM – Serviço Geológico do Brasil. 24 pp. Acessed at http://www.cprm.gov.br/rehi/atlas/piaui/relatorios/118.pdf 15 June 2015

Almeida, W.R. (2013). Macroalgas marinhas bentônicas da Ilha Bimbarras, Região Norte da Baía de todos os Santos, Bahia, Brasil. Dissertação (Mestrado). Feira de Santana: UEFS. 408p. Accessed at http://www2.uefs.br/ppgbot/pdf_dissertacoes_teses/mestrado/2013/Almeida%202013_Macroalgas%20Marinhas%20Bent%C3%B4nicas%20da%20Ilha%20Bimbarras,%20Regi%C3%A3o%20Norte%20da%20Ba%C3%ADa%20de%20Todos%20os%20Santos,%20Bahia,%20Brasil.pdf 15 June 2015.

Alves, M. H. & Carvalho, L. M. O. (2012). Macroalgas verdes da APA Delta do Parnaíba, Litoral Piauiense. pp. 20- 33, In: Guzzi, A. (Org). Biodiversidade do Delta do Parnaíba: litoral piauiense. Parnaíba. Accessed at http://bionoset.myspecies.info/sites/bionoset.myspecies.info/files/Biodiversidade%20do%20Delta%20do%20Parna%C3%ADba_0.pdf 16 June 2015

Amaral, A. C. Z & Migotto, A. E. (2011). In: Amaral, A. C. Z; Nallin, S. A. H. ( Org.) Biodiversidade e ecossistemas bentônicos marinhos do litoral norte de São Paulo, Sudeste do Brasil. Campinas: UNICAMP/IB. 574pp.

Assis, T. K. C., Costa, M. O. & Alves, M. H. (2014). Estudo das Macroalgas Bentônicas ocorrentes em três praias do Piauí e sua importância ambiental. Anais... Congresso Nacional de Educação. Campina Grande, PB. Acessed at http://www.editorarealize.com.br/revistas/conedu/trabalhos/Modalidade_1datahora_14_08_2014_15_41_41_idinscrito_3641_3b885df1687638a9a098ca46746fb3a1.pdf 20 May 2015

Barata, D. Taxonomia e filogenia do gênero Caulerpa J.V.Lamour. (Bryopsidales, Chlorophyta) no Brasil. (2008). Tese (Doutorado). São Paulo: Instituto de Botânica da Secretaria de Estado do Meio Ambiente: 200 pp. Accessed at http://www.ambiente.sp.gov.br/pgibt/files/2013/10/Diogina_Barata_DR.pdf 16 June 2015.

Batista, M. G. S. (2011). Algas marinhas bentônicas do litoral do Estado do Piauí: contribuição ao conhecimento e preservação. pp 40-55, In: Santos Filho, F. S. & Soares, A. F. C. L. (Org). Biodiversidade do Piauí: pesquisas & perspectivas. 1 edição. Curitiba, PR: CRV. 2011.

Baptista, E. M. C. (2004). Caracterização e importância ecológica e econômica dos recifes da zona costeira do Estado do Piauí. Dissertação (Mestrado). Teresina: Universidade Federal do Piauí – UFPI. 290p. Accessed at http://www.leg.ufpi.br/mestambiente/index/pagina/id/2521 14 June 2015

Bicudo, C. E. M. & Menezes, M. (2010). Introdução: As algas do Brasil. pp. 49-60, In: Forzza, R.C. et al. (Org). Catálogo de plantas e fungos do Brasil [online].: Instituto de Pesquisas Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro, Vol. 1. Accessed at http://reflora.jbrj.gov.br/downloads/vol1.pdf 16 June 2015.

Carvalho, L. M. O & Alves, M. H. (2011). Biodiversidade de macroalgas bentônicas do Piauí. Anais...XX Seminário de Iniciação Científica e III Seminário em Desenvolvimento Tecnológico e Inovação. Acessed at http://leg.ufpi.br/20sic/Documentos/RESUMOS/Modalidade/Vida/f33ba15effa5c10e873bf3842afb46a6.pdf 02 July 2016.

Cordeiro-Marinho, M., Yamaguishi-Tomita, N. & Guimarães, S. M. P. B. (1984). Algas. pp. 8-13, In: Fidalgo, O and Bononi, V.L.R. Técnicas de coleta, preservação de material botânico. São Paulo: Instituto de Botânica.

Copertino, M. S. & Mai, A. C. G. (2010). Algas. pp. 42-55, In: Mai, A.C.G. and Loebmann, D. (Org). Guia ilustrado: Biodiversidade do litoral do Piauí. 1a edição. São Paulo: Paratodos, Sorocaba.

Correia, M. D. (2005). Biodiversidade Costeira. pp. 29-46, In: Correia, M. D. & Sovierzoski, H.H. (Org). Ecossistemas marinhos: recifes, praias e manguezais. Maceió: EDUFAL. Accessed at http://www.ufal.edu.br/usinaciencia/multimidia/livros-digitais-cadernos-tematicos/Ecossistemas_Marinhos_recifes_praias_e_manguezais.pdf 01 July 2015.

Dawes, C. J. (1986). Botanica Marina. México: D.F. Editorial Limusa. 673pp.

Goulart, M. & Callisto, M. (2003). Bioindicadores de qualidade de água como ferramenta em estudos de impacto ambiental. Revista da FAPAM 2(1). http://www.santoangelo.uri.br/~briseidy/P%F3s%20Licenciamento%20Ambiental/bioindicadores%2019.10.2010.pdf

Horta, P. A., Amancio, E., Coimbra, C. S. & Oliveira, E. C. (2001). Considerações sobre a distribuição e origem da flora de macroalgas marinhas brasileiras. Hoehnea 28(3): 243-265. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/235351335_Considerations_on_the_distribution_and_origin_of_the_marine_macroalgal_Brazilian_flora

Jaenicke, L. (1977). Sex hormones of brown algae. Naturwissenschaften. 64: 69-75. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2FBF00437346

Joly, A. B. (1965). Flora Marinha do Litoral Norte do Estado de São Paulo e regiões circunvizinhas. Separata do Boletim da Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras, USP, Botânica. 21:1-267. http://www.revistas.usp.br/bolfflchsb/article/view/58428/61424

Lee, R. E. 2008. Phycology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 534pp.

Oliveira, E. C., Österlund, K. & Mtolera, M. S. P. (2005). Marine Plants of Tanzania: A field guide to the seaweeds and seagrasses. Stockholm: Stockholm University. 267pp.

Oliveira, E. C., Horta, P. A., Amancio, E. & Sant’anna, C. L. (1999). Algas e angiospermas marinhas bênticas do litoral brasileiro: diversidade, explotação e conservação. In: Workshop sobre Avaliação e ações prioritárias para a conservação da biodiversidade das zonas costeira e marinha. Relatório Técnico. Brasília: Ministério do meio Ambiente. Accessed at http://www.anp.gov.br/brasil-rounds/round8/round8/guias_r8/perfuracao_r8/%C3%81reas_Priorit%C3%A1rias/plantas_marinhas.pdf 01 July 2015

Oliveira Filho, E. C. (1977). Algas marinhas bentônicas do Brasil. Tese de Livre-Docência do Departamento de Botânica. São Paulo.: Universidade de São Paulo. 407 pp.Accessed at http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/livredocencia/41/tde-14032013-171424/pt-br.php 01 June 2015

Ortega, J. L. G. (2000). Algas. pp. 109-193, in: Lanza-Espino, G., Pulido S.H., Pérez, J.L.C.P. (Eds.). Organismos indicadores de la calidad del agua y de la contaminación (Bioindicadores). México: Playa y Valdés.

Santana, W. M., Silva-Leite, R. R., Silva, K. P. & Machado, R. A. (2009). Primeiro registro de nidificação de tartarugas marinhas das espécies Eretmochelys imbricata (Linnaeus, 1766) e Lepidochelys olivacea(Eschscholtz, 1829), na região da Área de Proteção Ambiental Delta do Parnaíba, Piauí, Brasil. Pan-American Journal of Aquatic Sciences 4(3): 369-371. http://www.panamjas.org/pdf_artigos/PANAMJAS_4(3)_369-371.pdf

Santos, A. A. & Moura, C. W. N. (2011). Additions to the epiphytic macroalgae flora of Bahia and Brazil. Phytotaxa 28: 53-64. http://www.periodicos.ufc.br/index.php/arquivosdecienciadomar/article/viewFile/136/136

Santos Filho, F. S. (2009). Composição florística e estrutural da vegetação de restinga do Estado do Piauí. Tese (Doutorado) Recife: Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco. 124p. Accessed at http://200.17.137.108/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo=354 10 June 2015

Santos Filho, L. G. A., Vieira, S. G. A., Santiago, A. P. & Santiago, J. A. S. (2012). Epifitismo em uma população de Sargassum vulgare C. Agardh (Phaeophyceae: Fucales) na praia do Coqueiro, Piauí, Brasil. Arquivos de Ciência do Mar 45(2): 77-80. http://www.periodicos.ufc.br/index.php/arquivosdecienciadomar/article/viewFile/136/136

Voltolini, J. C., Batista, M. G. S. & Nascimento, E. F. I. (2012). Macroalgae species richness in beaches with consolidated arenite substrata and reef-pools with sandy bottoms in Piauí. Brazilian Journal of Ecology 1(14): 115-123. http://www.seb-ecologia.org.br/Revista%20SEB%2014%20final.pdf

Vidotti, E. C. & Rollemberg, M. C. E. (2004). Algas: da economia nos ambientes aquáticos à biorremediação e à química analítica. Química Nova 27 (1): 139-145. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/qn/v27n1/18822.pdf

Wynne, M. J. (2011). A checklist of benthic marine algae of the tropical and subtropical western Atlantic: third revision. Nova Hedwigia 140:1-166.

Yoneshigue-Valentin, Y., Gestinari, L. M. S. & Fernandes, D. R. P. (2006). Macroalgas. pp. 67-105, in: Lavrado, H. P.; Ignacio, B.L. (Org.). Biodiversidade bentônica da região central da Zona Econômica Exclusiva brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Museu Nacional.

1. Graduated in Biology of Federal University of Piauí, Ministro Reis Velloso Campus. Avenida São Sebastião, 2819, CEP 64202-020, Parnaíba, PI, Brazil. E-mail: tuany.kelly@gmail.com

2. Federal University of Piauí, Ministro Reis Velloso Campus. Avenida São Sebastião, 2819, CEP 64202-020, Parnaíba, PI, Brazil. E-mail: malves@ufpi.edu.br