HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN

HOME | ÍNDICE POR TÍTULO | NORMAS PUBLICACIÓN Espacios. Vol. 37 (Nº 25) Año 2016. Pág. 18

Julio César ACOSTA-Prado 1; Rodrigo Arturo ZÁRATE Torres 2; Manuel Alfonso GARZÓN Catrillón 3

Recibido: 24/04/16 • Aprobado: 29/05/2016

ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the relationship between the 12 attributes of followers by Antelo, Prilipko, and Sheridan (2010), and the four areas of emotional intelligence by Wong and Law (2002). The descriptive-correlational empirical study was conducted in a sample of 323 Colombian followers. The results show, that there is a positive correlation between the attributes of employees and their emotional intelligence and, however, there is no direct correlation between the attribute tolerance and the area of empathy of emotional intelligence. This situation shows that Colombian followers have a low capacity to understand and comprehend the emotions of the members of their teams. |

RESUMEN: Este artículo analiza la relación entre los 12 atributos de los colaboradores de Antelo, Prilipko, y Sheridan (2010), con las 4 áreas de la Inteligencia emocional (IE) de Wong y Law (2002). El estudio empírico de tipo descriptivo correlacional, se realizó en una muestra de 323 colaboradores colombianos. Los resultados muestran, que existe una correlación positiva, entre los atributos de los colaboradores y su inteligencia emocional; sin embargo, no existe una correlación directa entre el atributo de tolerancia de los colaboradores y el área de empatía de la IE. Esta situación muestra que los colaboradores colombianos tienen una baja capacidad para entender y comprender las emociones de los miembros de sus equipos de trabajo. |

Leadership has several components, including the leaders and followers that for the purposes of this study will be named followers. Much has been written about leaders but little about followers. Within existing theories about employees, one of the most recents is the Rainbow of Followers' Attributes in a Leadership Process developed by Antelo, Prilipko, and Sheridan (2010). The theory expresses 12 attributes that followers have. The authors also developed a tool that is used to measure how each individual is in each of the attributes, instrument that was used in this study.

On the other hand, one issue that is at a great extent responsibility of leaders is emotional intelligence, which for this study was also decided to measure in each of the participants and in the four areas of emotional intelligence worked by Wong and Law (2002) to identify if there is a positive relationship between employees, and areas of emotional intelligence.

In addition, several control variables including age, gender, level of education and experience in personnel management were established in order to determine if a positive relationship between these variables and the attributes of followers and emotional intelligence also existed.

The results indicate that there is a positive relationship between the attributes of followers and the emotional intelligence, meaning that followers with higher emotional intelligence may show higher job performance. Similarly, it was found that there is a positive relationship between age, gender and experience in handling personnel with some of the attributes of followers and some of the areas of emotional intelligence.

2.1. Attributes of followers

As a pioneer in the issue of followers, Zaleznik (1965) writes about the dynamics of followers sorting their own patterns and dynamics into four big groups that are influenced by control and behavior.

Thus following Chaleff (1995), being a good follower is seen as a skill that requires courage, while blind obedience is not necessarily the quality of a good follower, on the other hand being a good leader means being a good follower and vice versa.

In leadership, there are two main players: leaders and followers. The latter for purposes of this document will be denominated followers. Worldwide, much has been written about leaders, however, the issue of follower has been little studied (Brown and Thornborrow, 1996; Thornborrow, 1994) and according to Bennis (2008), it is an issue that is booming, and day by day there is more interest in studying and analyzing followers.

Therefore, neither leadership nor management would exist without followers (Hollander and Kelly, 1992; Lundin and Lancaster, 1990; Vecchio, 1987). Additionally, the effectiveness of a leader is largely determined by the efficiency and success of his or her followers (Yukl, 2002).

The study of followers is based mainly on two reasons, the first one is to carry out complementary studies about leadership, and the second one is directly related to the followers, for when studying and determining the behavior of the effective followers, training processes can be designed within organizations aimed at developing the skills and behaviors associated with effective followers, and so achieve not only an improvement in followers since this will also be a direct impact in the improvement of organizations (Brown and Thornborrow, 1996; Buhler, 1993).

There are very few theories about the classification and behavior of followers; among the most prominent and in chronological order, we will find authors like Chaleff (1995), Kelley (1992), and Zaleznik (1965), whose best known work is the book entitled The Courageous Follower. The most contemporary authors and that have stated their theories about the followers in this century are Kellerman (2007) with her theory called the Follower Continuum, and the authors Antelo et al. (2010) with their theory of the Rainbow of Followers' Attributes in a Leadership Process. The latter is the base of the present study, therefore, only this theory will be deepened herein.

Firstly, based on Zárate and Acosta-Pardo (2012), we will address the notion of attribute, which may be extended by the concept of the attribution theory developed by Kelley (1992), this theory says that leadership is an attribution people assume about other individuals.

Now, it is important to consider that leaders are generally characterized or identified to possess general attributes such as intelligence and social skills, among others. Hence the authors Antelo et al. (2010) developed their theory and instrument based on the possibility that followers could also have different attributes that would characterize them, especially the highly effective followers. From there, they developed the Rainbow of Followers' Attributes in a Leadership Process which contains 12 attributes that can be determined by using the instrument with the same name that grades each attribute on a numerical scale from one to five, being one the lowest score and five the highest score. Following, the 12 attributes according to Antelo et al. (2010) are explained:

The contributions of McClelland (1961), McClelland (1989), and McClelland and Winter (1969) in the field of labor motivation form the current paradigm and has not yet been overcome.

The theory of achievement motivation for McClelland and Winter (1969) is the continuation of The Law of Effect by Thorndike, according to which all seek to obtain rewards and avoid punishment.

Therefore, the following questions apply: are the tendencies of seeking for success and avoiding failures equally strong in all of us? An approximation to an answer is that there are rooted people who do not hesitate to expose to failure when it comes to pursue success, and there are conservative people who give up their chances of success so as not to take risks.

The achievement motive according to McClelland (1989) goes from finding satisfaction to avoiding setbacks, and is very important in leadership and management positions as it will decisively determine the style of decision making and the response to threats and opportunities.

The theory of McClelland (1961) is linked to learning concepts. According to him, human needs are learned and acquired during people's lives. The same way as Maslow (1954) and Alderfer (1969), McClelland focuses on three basic needs: achievement, power and affiliation.

These three needs determined in McClelland (1961), McClelland (1989), and McClelland and Winter (1969) are learned and acquired in the course of life as a result of personal experiences. Considering that the needs are learned, the rewarded behavior tends to be repeated with more frequency. Consequently, people develop unique patterns of needs that affect their behavior and performance. The theory allows the administrator to locate the presence of these needs in itself and in subordinates so as to create a work environment that favors the need profiles that are localized.

It is important to begin by stating that the term emotional intelligence was coined by Salovey and Mayer (1990) and defined by the authors as "the ability to monitor oneself and other people's feelings and waves of emotions, discriminate among them and use this information to guide our own actions and thoughts"; a kind of social intelligence, that includes the ability to control our own emotions and those of others, as well as to discriminate between them and use the information that is provided in order to guide our thinking and our actions.

In other words, it refers to a person's ability to understand its own emotions and those of others, and express them in ways that are beneficial for itself and for the culture to which it belongs to. For these authors, emotional intelligence includes verbal and nonverbal assessment, emotional expression, regulation of emotion in oneself and in others, and the use of emotional content in the solution of problems (Mayer and Salovey, 1993). Salovey and Mayer (1990), gather the personal intelligences of Gardner (1993) in their basic definition of emotional intelligence, and expand them into five main domains:

The term Emotional Intelligence is a paradox according to Chopra and Kanji (2010), because it contains two terms that are contradictory and complex, as emotions are subjective and intelligence is objective. These two authors mention that in order to define emotional intelligence, one should start defining each of the terms independently.

According to Salovey and Mayer (1990), the concept of intelligence has evolved over time. It has been defined differently at different times or periods. One of the definitions of intelligence corresponds to Thurstone (1938), who defines intelligence as a set of seven mental skills that explain various aspects of performance (Cartwright and Pappas, 2008; Salovey and Mayer, 1990).

The results of recent studies by Herrnstein and Murray in 1994, and Gardner in 1995 reveal that they only predict 20% of relative success in life; it can therefore be deduced that the cognitive theory, despite its great progress and sophistication, cannot by itself explain many of the problems that arise and that have not yet obtained a convincing answer.

The concept of emotional intelligence emerges based on Goleman (1995) as an attempt to highlight the role of emotions in our intellectual life and our social adaptation and personal balance. For this author, the concept of emotional intelligence is important because among other things, it constitutes the link between feelings, character and moral impulses.

According to Chopra and Kanji (2010), the word intelligence comes from the Latin intellegere, which means to understand. These two authors mention that the term intelligence is related to logic, planning, reasoning, thinking, learning and problem solving.

Chopra and Kanji (2010) say that emotions are usually associated with mood, temperament, personality and disposition. As for emotions, Zárate and Matviuk (2010), mention that "Chopra and Kanji (2010) define emotion as a mental and psychological state with a wide variety of feelings, thoughts and behaviors. From Goleman (1995), we learn that "the root of the word emotion is motere, the Latin verb 'move' in addition to the prefix 'e' which implies moving away, suggesting that in every emotion there is an implicit tendency to act".

Similarly, Zárate and Matviuk (2010) mentioned that Vigoda-Gadot and Meisler (2010) argue that nowadays, the consensus on the definition of emotions is very well summarized by Mayer, Roberts and Barsade (2008) who define emotions as coordinated responses to changes in the environment that involve remembering specific subjective experiences, activating relevant knowledge, coordinating body states for preparedness to certain reactions, and evaluating the process of changing situations.

Meanwhile, Aslan and Erkus (2008) say that the first authors to define emotional intelligence were Salovey and Mayer in 1990. Salovey and Mayer (1990) mention that emotional intelligence is the recognition and use of emotional states, own and from others, in order to solve problems and regulate behavior, and it consists of a set of mental processes that involve emotional information. This mental process includes assessment and expression of one's own emotions and those of others, and the use of emotions in adaptive ways.

Analyzing the different definitions, we can identify three common elements:

• the ability to identify and discriminate our own emotions and those of others,

• the ability to manage and regulate those emotions, and

• the ability to use them in an adaptive manner.

These three elements seem to be the focus of the definitions and theories developed to explain the emotional intelligence.

Although the concept of emotional intelligence was first developed by Salovey and Mayer (1990), it won popularity with the studies developed by Goleman (1995). According to Geher, Warner and Brown (2001), emotional intelligence is the individual awareness of one's own emotions and the correct interpretation of the emotions of others, and it is valued as other type of social intelligence.

Empirical studies such as those of Davies, Stankov, and Roberts (1998), Fox and Spector (2000), and Van Rooy and Viswesvaran (2004), support the independence between intelligence and emotional intelligence, and the relationship of the latter with personality. It is important to note that no theory has been able to define the role of emotional intelligence and its relation with the results of the work carried out (Wong and Law, 2002). As noted by Van Rooy and Viswesvaran (2004) has yet to be determined whether emotional intelligence affects performance consistently or it differs depending on the type of tasks (e.g., academic vs. labor) and other potential variables.

Separately, Conte (2005) warns that there is no much room for greater predictive power of emotional intelligence on certain criteria such as performance and leadership, as self-report measures have correlations with personality variables. However, there are studies that show the predictive power of emotional intelligence in academic and professional contexts.

From the research conducted by Jordan (2000), it is rescued that the study found relations with academic achievement in students; in the results of Sue-Chan and Latham (2004), the authors found a strong relationship with teamwork and academic performance; meanwhile, Jordan, Ashkanasy, Härtel and Hooper (2002) found associations from the Workgroup Emotional Intelligence Profile (WEIP) with measured performance such as goal orientation and process efficiency; in the research by Wong and Law (2002), the results indicate that emotional intelligence predicts performance on tasks in the workplace; and Mayer, Caruso and Salovey (1999) contribute that it predicts pro-social behavior.

The results obtained by Aslan and Erkus (2008) are aimed at showing that emotional intelligence is equally or more important than intelligence quotient (IQ) in business and professional life, and the research by Radhakrishnan and UdayaSuritan (2010) manifests that emotional intelligence gives managers and their followers the ability to sense what others need and want, and develop strategies to meet those needs and desires.

Wong, Wong and Law (2007) state that emotional intelligence has been proposed as an important and potential construct for Human Resources Management; they also mention that in recent years the relationship between emotional intelligence and performance has been more evident in studies in China.

In the review, we can assert that in the broader context of the relationship between emotional intelligence, performance and professional success of individuals, some assertions allow summarizing findings (Cherniss, 2000; Dulewicz and Higgs, 2000; Farnham, 1996; Goleman, 1995, Goleman, Boyatzis, and McKee, 2001, 2002; Salovey and Mayer, 1990; Steiner, 1997; Wong and Law, 2002):

This fact, added to the conviction that comes from common sense, helps us understand the reasons why several projects and training events designed to promote emotional intelligence have emerged (Cherniss, 2000; Goleman, 1995; Goleman et al. 2002; Salovey, Mayer and Caruso, 2002).

Based on the above, we can say that although emotional intelligence has a component of genetic root, the revised research suggests that training can also produce effects and the research and practice clearly show that "emotional intelligence can be learned" (Goleman et al. 2002).

In countries such as Colombia and Latin America in general, no studies have been carried out to determine whether there is a relationship between emotional intelligence and performance. This study makes that correlation between emotional intelligence and effectiveness of followers.

2.2.1. Variables used for measuring Emotional Intelligence

Although there are several instruments to measure emotional intelligence, there is also a consensus that defines emotional intelligence as the ability of people to deal with emotions and that comprises the following four areas (Mayer et al. 1999; Salovey and Mayer, 1990; Wong, Wong, and Law, 2004; Wonget al. 2007; Acosta-Prado, Zárate and Pautt, 2015):

In the previous review we consider a number of questions, and the question that our research wants to answer is whether it is appropriate to determine the positive relationship between the 12 followers' attributes and the four areas of emotional intelligence, so that we can clarify the role that these variables represent to determine the relationship between the attributes of followers and their emotional intelligence.

The results presented in this paper are the product of a descriptive research as it seeks to specify and describe individuals or sample groups regarding the results or properties obtained in the variables of the mentioned model; a correlational study is considered since correlations between the structuring variables, and comparisons with gender, level of education, experience, number of direct employees and the sector to which the organization belongs to are established.

To carry out the empirical study, a total of 323 Colombian followers were surveyed. The instruments that were used include "12 followers' attributes" by Antelo et al. (2010), and "Measuring emotional intelligence" by Wong and Law (2002).

Sampling was carried out in a non-probabilistically manner and it was a sampling for convenience. That is, certain groups were non-probabilistically located, but the people for the sample were probabilistically chosen, seeking for them to meet the requirements above.

The study focuses on Colombian followers who share similar demographic characteristics such as age, gender, education, and experience in personnel management (table 1). Management data were obtained from secondary sources such as databases of chambers of commerce, business directories available on the Internet, and publications of Colombia during the period 2014-2015.

Followers completed the questionnaire in-person. The questionnaire identified the industry, which was categorized as: banking and finance, hospitality and tourism, biosciences and chemistry, environment and renewable energy, new materials and engineering, information technology, and services.

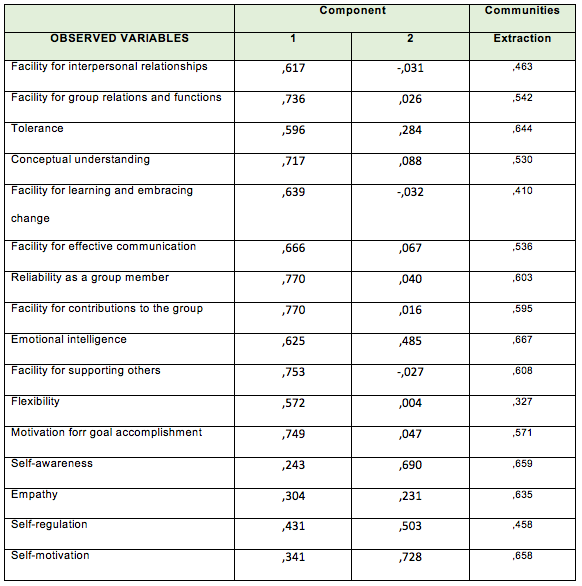

The information collected was analyzed using the SPSS software. The objective was to simplify the data summarizing the information contained in a large number of observed variables from Likert type for fewer measures called factors, which did not have a hypothesis about their number nor their structure. Initially, general analyzes were performed including Cronbach's alpha, after that the average and standard deviations for each of the attributes were obtained. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) based on principal components analysis was performed.

The EFA studies all possibilities, to finally select the most likely, according to the data collected (Uriel & Aldás, 2005). It also ensures the unidimensionality, reliability, convergent and discriminant validity thereof.

As mentioned, there has been an EFA from the technique of principal components and rotation Quartimax iterated. Before it was calculated the coefficient alpha reliability of Cronbach Bartlett and contrast for the 16 observed variables distributed as follows: 39 items related to the 12 followers' attributes, measured with a Likert scale of 5 points (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally 4 = often 5 = always), and 16 items related to the 4 areas of emotional intelligence measured with a Likert scale of 7 points, used in the questionnaire from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample

Source: Own elaboration

Table 2 shows the overall results of the rainbow of followers' attributes. It can be seen that the attribute with the lowest score is emotional intelligence, followed by flexibility. The results suggest that Colombian followers do not know how to use their emotions to cope with changes and furthermore, they are not flexible to change; instead, they are given to routine and tradition.

Table 2. Overall results of the of 12 followers' attributes

Source: Own elaboration

Table 3 shows the results of the application of the instrument by Wong and Law (2002), which determines that the latent weakness of followers is to assess and understand the emotions of others, that is to say, generating empathy while their strength lie on regulating their emotions, meaning that they are able to leave their emotional setbacks very quickly.

Tabla 3. Overall result of emotional intelligence

Source: Own elaboration

The statistical results of the scale show the following values: Cronbach's alpha yielded a value of 0.873 which is higher than the 0.70 minimum value recommended by Nunnaly (1978), indicating that the data are reliable. Therefore, the scale is reliable and there is intercorrelation between the variables of the scale (Cronbach, 1951; Thiétart, 2003). The measure of sampling adequacy Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin is 0.919, which means that the ratio between the variables is high. Bartlett's test (χ2 =2019.952, df =120, and p =0.000) rejects the null hypothesis of no significant correlation between the observed variables. In conclusion, it is appropriate to apply the analysis of principal components to the variables.

There were identified two factors: attributes of followers and emotional intelligence. These two factors explain 55.653% of the total variance of the observed variables. The EFA results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Rotated Component Matrix*

*Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis.

Rotation Method: Quartimax with Kaiser Normalization.

Rotation converged in 4 iterations.

Source: Own elaboration

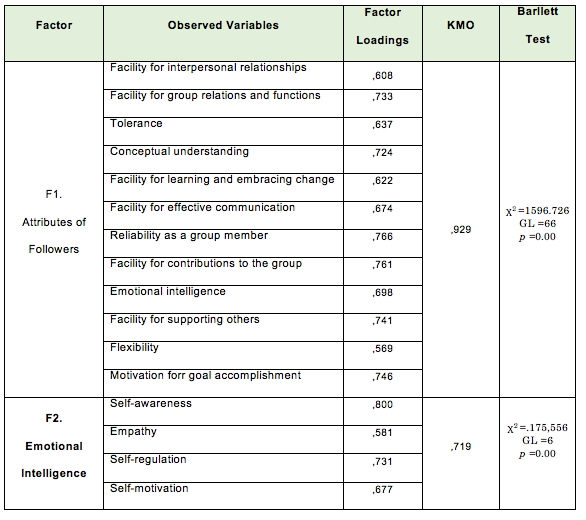

Then it was proceeded to compare and re-specify, through a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the above two factors. To do this, performing this second sequence in the factor analysis to overcome the limitations of the principal components method, was considered appropriate and thus to be able to contrast and refine new extracted factors.

The desire is to strengthen the dimensionality of the factors, the reliability of each as well as the convergent and discriminant validity. Once the CFA the corresponding re-specifications were made, the following two factors were identified, attributes of followers and emotional intelligence, described below. The CFA results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5. CFA results - observed variables and results from factors

Source: Own elaboration

As shown in Table 5, the two factors obtained demonstrate significant results. With regard to internal consistency, Cronbach's alpha is calculated with the final variables in each factor. For factor 1 Cronbach's alpha has a value of 0.896, and factor 2 of 0.791. According to the literature, the factor 1 shows good internal consistency and the factor 2 acceptable. Therefore, we conclude that there is convergent validity, reliability and internal consistency of both the scale factors and grouped.

Note that in the exploratory and confirmatory sequence of factor analysis, it was found that the dimensions of attributes of followers and emotional intelligence, identified in Colombian followers are developed as joint processes that favor the efficient management of followers and major understanding of business context. Table 6 shows the correlation between the attributes of followers and the 4 areas of emotional intelligence.

Table 6. Correlation between the attributes of followers and areas of emotional intelligence

** The correlation is significant at level 0,01 (bilateral).

* The correlation is significant at level 0,05 (bilateral).

Source: Own elaboration

The results show that there is a positive correlation between the attributes of followers and the four areas of emotional intelligence. The only point where there is no direct correlation between the attribute of tolerance and empathy area of emotional intelligence. Therefore, Colombian followers are not tolerant for to evaluate and understand the emotions of others.

The overall result shows that in order to efficiently develop the followers, their managers must have high capacity of emotional intelligence.

Table 7 provides an additional perspective where the control variables for each of the attributes and the four areas of emotional intelligence are related.

Table 7. Correlation between the attributes of followers, areas of emotional intelligence, and control variables (all variables)

** The correlation is significant at level 0,01 (bilateral).

* The correlation is significant at level 0,05 (bilateral).

Source: Own elaboration

Gender is definitely the area that associates the most with the attributes of followers and with emotional intelligence. Gender is directly related with the facility for effective communication, motivation for goal accomplishment, and empathy. On the other hand, the level of education does not have any direct relation to the attributes of followers nor the four areas of emotional intelligence.

In terms of age, it has a positive relationship with the facility for learning and embracing change. Regarding the experience in personnel management, it has a positive relationship with the ease of learning and coping with change, facility for effective communication, and self-motivation.

The results show that there is a positive correlation between the 12 attributes of followers and the four areas of emotional intelligence except for the attribute of tolerance in relation to the assessment and understanding of others' emotions. In a practical way, this shows that there is a low capacity of followers to solve conflict that emerges between them in the same team.

The results are conclusive, very telling and usable by organizations, because it shows that emotional intelligence affects the performance of followers. Therefore, organizations should seek to train their employees in emotional intelligence if they want higher performance in their followers. However, the empirical study has a temporal limitation because it is a cross-sectional study (2014 – 2015).

It can also be concluded that learning and handling changes are easier tasks for people who have experience in managing staff. Additionally, they develop a better assertive communication.

The proposal is to conduct deeper studies for each of the control variables and similar studies in other countries in order to compare and to determine if culture has some influence on the results presented here.

Acosta-Prado, J.C., Zárate, R.A., & Pautt, G.M. (2015). Characterization of emotional intelligence in Colombian managers. Universitas Psychologica, 14(3), 815-832. http://dx.doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy14-3.ceic

Alderfer C.P. (1969). An empirical test of new theory of human need. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4(1), 142–175.

Antelo, A., Prilipko, E.V., & Sheridan-Pereira, M. (2010). Assessing effective attributes of followers in a leadership process. Contemporary Issues in Education Research (CIER), 3(9), 33-44.

Aslan, S. & Erkus, A. (2008). Measurement of emotional intelligence: Validity and reliablity studies of two scales. World Applied Science Journal, 4 (3), 430-438.

Bennis, W. (2010) Art of followership. Leadership Excellence, 27(1), 3-4.

Brown, A.D. & Thornborrow, W.T. (1996). Do organizations get the followers they deserve? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 17(1), 5-11.

Buhler, P. (1993). The flip side of leadership–cultivating followers. Supervision, 54, 17-19.

Cartwright, S. & Pappas, C. (2008). Emotional intelligence, its measurement and implications for the workplace. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10(2), 149-171.

Chaleff, I. (1995). The courageous follower: Standing up to and for our leaders. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Cherniss, C. (2000). Emotional intelligence: what it is and why does it matters. In Annual meeting of the society for industrial and organizational psychology. New Orleans, LA: SIOP.

Chopra, P.K. & Kanji, G.K. (2010). Emotional intelligence: A catalyst for inspirational leadership and management excellence. Total Quality Management, 21(10), 971-1004.

Conte, J.M. (2005). A review and critique of emotional intelligence measures. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 433-440.

Cronbach, L.J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16(3), 297-334.

Davies, M., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R.D. (1998). Emotional intelligence: in search of an elusive construct. Journal of personality and social psychology, 75(4), 989-1015.

Dulewicz, V. & Higgs, M. (2000). Emotional intelligence-A review and evaluation study. Journal of managerial Psychology, 15(4), 341-372.

Farnham, A. (1996). Are you smart enough to keep your job? The Fortune, 133(1), 34-36.

Fox, S. & Spector, P.E. (2000). Relations of emotional intelligence, practical intelligence, general intelligence, and trait affectivity with interview outcomes: It's not all just 'G'. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 203-220.

Gardner, H. (1993). Inteligencias múltiples: la teoría en la práctica. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

Geher, G., Warner, R.M., & Brown, A.S. (2001). Predictive validity of the emotional accuracy research scale. Intelligence, 29(5), 373-388.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York, NY: Bantam Books.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2001). Primal leadership: The hidden driver of great performance. Harvard Business Review, 79(6), 42-51.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & Mckee, A. (2002). Primal leadership: Realizing the power of emotional intelligence. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Hollander, E.P. & Kelly, D.R. (1992). Appraising relational qualities of leadership and followership. International Journal of Psychology, 27(3-4), 289-290.

Jordan, P.J. (2000). Measuring emotional intelligence in the workplace: A comparison of self and peer ratings of emotional intelligence. In Emotional Intelligence at work: Does it make a difference - Academy of Management Conference Proceedings. Toronto, Canadá.

Jordan, P.J., Ashkanasy, N.M., Härtel, C.E., & Hooper, G.S. (2002). Workgroup emotional intelligence: Scale development and relationship to team process effectiveness and goal focus. Human Resource Management Review, 12(2), 195-214.

Kellerman, B. (2007). What every leader needs to know about followers. Harvard Business Review, 85(12), 84-91.

Kelley, R. E. (1992). The power of followership: How to create leaders people want to follow, and followers who lead themselves. New York, NY: Doubleday Currency.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Litwin, G.H. & Stringer, R.A. (1968). Motivation and organizational climate. Boston:

Harvard Business School Press.

Lundin, S.C. & Lancaster, L.C. (1990). Beyond leadership: the importance of followership. The Futurist, 24(3), 18-22.

Maslow A.H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper and Row.

Mayer, J.D., Caruso, D.R., & Salovey, P. (1999). Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence, 27(4), 267-298.

Mayer, J.D., Roberts, R.D., & Barsade, S.G. (2008). Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 507–536.

Mayer, J.D. & Salovey, P. (1993). The intelligence of emotional intelligence. Intelligence, 17(4), 433-442.

Mayer R.E. (1983). Pensamiento resolución de problemas y cognición. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

McClelland, D. (1961). The Achieving Society. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand.

McClelland, D. (1989). Estudio de la motivación humana. Madrid: Narcea Ediciones.

McClelland, D. & Winter, D. (1969). The Motivation Economic. New York, NY: Free Press.

Menkes, J. (2005). Executive intelligence: What all great leaders have. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory, (2nd ed). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Radhakrishnan, A. & UdayaSuriyan, G. (2010). Emotional intelligence and its relationship with leadership practices. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(2), 65-76.

Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211.

Salovey, P., Mayer, J.D., & Caruso, D. (2002). The positive psychology of emotional intelligence. In C.R. Snyder, & S.J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 159-171). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Salovey, P. & Sluyter, D.J. (1997). Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications. Nueva York: Basic Books.

Steiner, C. (1997). Achieving emotional literacy. London, UK: Bloomsbury.

Sue-Chan, C. & Latham, G.P. (2004). The situational interview as a predictor of academic and team performance: A study of the mediating effects of cognitive ability and emotional intelligence. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 12(4), 312-320.

Thiétart, R.A. (2003). Méthodes de Recherche en Management, Dunod, 2ème Edition.

Thornborrow, W.T. (1994). Follow my Leader: an investigation into the perceptions of follower types in the Hallifax Building Society. EME plc & Thornstons plc. MBA dissertation, School of Management and Finance, University of Nottingham.

Thurstone, L.L. (1938). Primary Mental Abilities, psychometric monographs, number 1. Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

Van Rooy, D.L. & Viswesvaran, C. (2004). Emotional intelligence: A meta-analytic investigation of predictive validity and nomological net. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), 71-95.

Vecchio, R.P. (1987). Effective followership: Leadership turned upside down. Journal of Business Strategies, 4(1), 39-47.

Vigoda‐Gadot, E. & Meisler, G. (2010). Emotions in management and the management of emotions: the impact of emotional intelligence and organizational politics on public sector employees. Public Administration Review, 70(1), 72-86.

Wong, C.S. & Law, K.S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. The leadership quarterly, 13(3), 243-274.

Wong, C.S., Wong, P.M., & Law, K.S. (2004). The interaction effect of emotional intelligence and emotional labor on job satisfaction: A test of Holland's classification of occupations. In C.E.J. Härtel, W.J. Zerbe, & N.M. Ashkanasy, (Eds.), Emotions in organizational behavior, 235–250. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Wong, C.S., Wong, P.M., & Law, K.S. (2007). Evidence of the practical utility of Wong's emotional intelligence scale in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(1), 43-60.

Yukl, G. (2002). Leadership in organizations (5th Ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Zaleznik, A. (1965). The dynamics of subordinacy. Harvard Business Review, 43(3), 119-131.

Zárate, R.A. & Antelo, A. (2014). Atributos de los Empleados Colombianos. Revista de Estudios Avanzados de Liderazgo, 1 (3), 17-27.

Zárate, R.A. & Matviuk, S. (2010). Expectativas de comportamiento del líder ideal colombiano del Sector Financiero Colombiano usando el Inventario de Prácticas de Liderazgo (IPL). Revista Escuela de Administración de Negocios, 69, 148-165.

Zaccaro, S.J. (2001). The nature of executive leadership: A conceptual and empirical analysis of success. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Zárate R.A. & Acosta-Pardo J.C. (2012). Importancia de las teorías acerca de los colaboradores en la gestión y liderazgo eficaces. Revista Escuela de Administración de Negocios, 73, 96-115.

1. Associate Professor at the Externado University of Colombia. Email: julioc.acosta@uexternado.edu.co

2. Full Professor at the EAN University. Email: razarate@ean.edu.co

3. Associate Professor at the EAN University. Email: mgarzon2.d@ean.edu.co